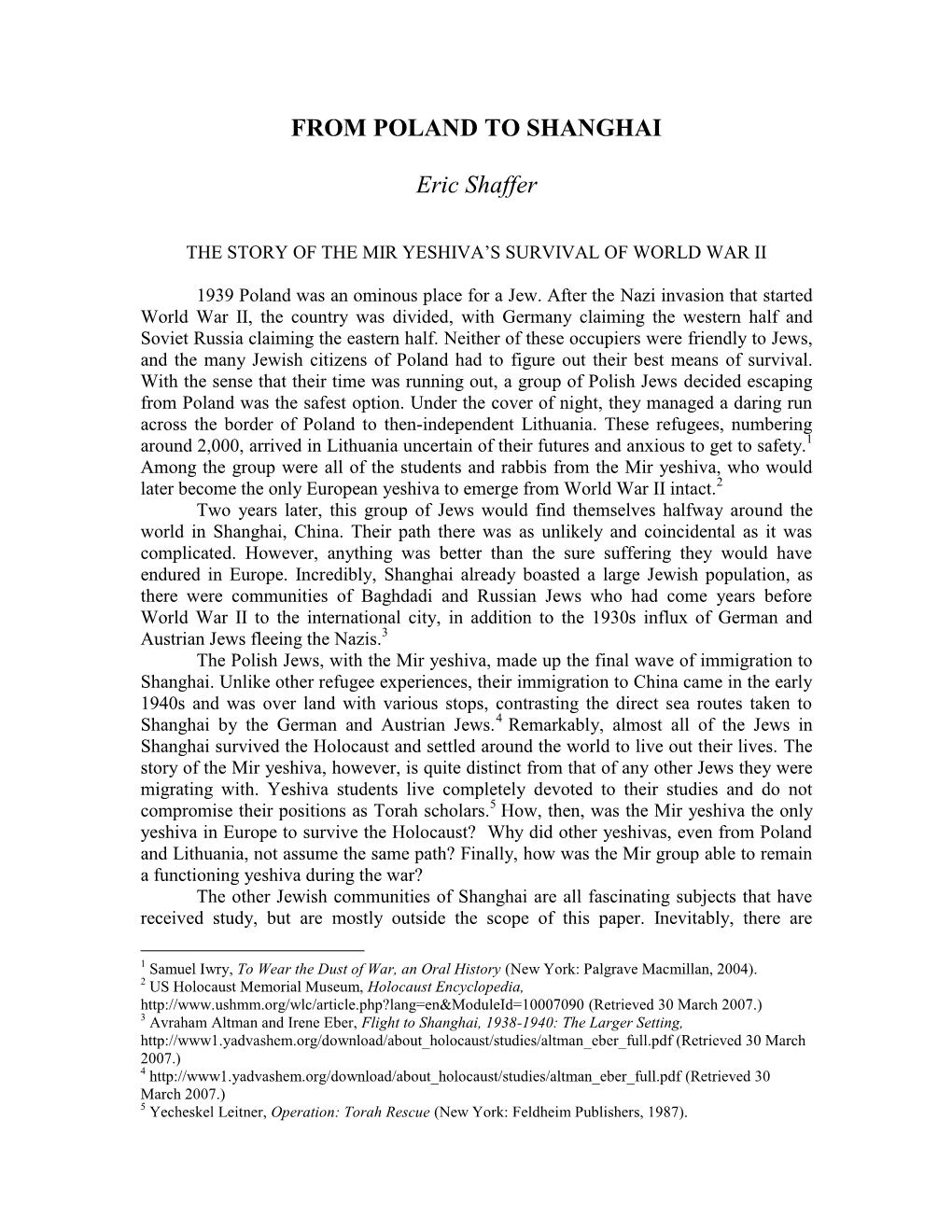

The Story of the Mir Yeshiva‟S Survival of World War Ii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Holocaust Remembrance Day - the Jerusalem Post

2021/1/27 Commemorating 'Visas for Life' on Holocaust Remembrance Day - The Jerusalem Post Jerusalem Post Opinion Commemorating 'Visas for Life' on Holocaust Remembrance Day Today the name of Sugihara Chiune adorns parks and streets, while exhibitions, films and documentaries tell the story of the Visas for Life. By MOTEGI TOSHIMITSU, GABRIELIUS LANDSBERGIS JANUARY 26, 2021 20:28 THE ʻSUGIHARA Houseʼ in Kaunas. (photo credit: SUGIHARA HOUSEʼ) Advertisement גם שואב אבק וגם שוטף רצפות מיועד לשאיבה, שטיפה וייבוש של כל סוגי הרצפות בנוחות אלחוטית. מתאים לניקוי שטיחים ופרקטים. bissell Listen to this article now 03:58 Powered by Trinity Audio https://www.jpost.com/opinion/commemorating-visas-for-life-on-holocaust-remembrance-day-656802 1/4 2021/1/27 Commemorating 'Visas for Life' on Holocaust Remembrance Day - The Jerusalem Post On International Holocaust Remembrance Day – the 27th of January – we commemorate the tragedy of the Holocaust and pay respect from the bottom of our hearts to the brave people who during those dark times went beyond their duty and took personal risk to save human lives. Among them is a Japanese diplomat, Sugihara Chiune (also known as Sempo), who helped thousands of Jewish people escape from Europe. In the autumn of 1939, some 35,000 refugees from Poland, then occupied by the Nazis and the USSR, fled to Lithuania seeking safety: families, children and elderly persons, students and people of different professions and religions. They left home, often without means of identification or subsistence, arrived in Lithuania, and were taken care of. Among those refugees were some young Jewish students from yeshivas in Kleck, Mir, Lomza, Kamenec, Grodno and Pinsk – world- famous Jewish educational institutions at the time. -

Student Handbook

YESHIVA HANDBOOK 5780/2019-2020 YESHIVA UNIVERSITY HIGH SCHOOL FOR BOYS THE MARSHA STERN TALMUDICAL ACADEMY 2540 AMSTERDAM AVENUE • NEW YORK, NY • 10033 PHONE: 212-960-5337 • FAX: 212-960-0027 • E-MAIL: [email protected] 1 Statement of Philosophy Yeshiva University High School for Boys emphasizes the core belief that Torah is at the center of our existence and represents the lens through which we look at all of life, as it guides our response to each and every opportunity and challenge. We therefore define our lives not only by the ongoing study of Torah, but by our complete dedication to the values and ideals of Torah. Simultaneously, we recognize that proper understanding of the sciences and humanities, examined through the prism of Torah, can further our appreciation of G-d’s great wisdom. It is by the light of both of G-d's expressions of His will - through revelation and creation, Torah U’Madda - that we interact with and impact the world around us. In light of the above, the yeshiva provides a challenging academic program in an atmosphere that expects and expresses adherence to the traditional ideals and practices of Orthodox Judaism. It is designed to motivate Torah living - striving to become ever more devoted to G-d, Torah learning, personal integrity, and the kind of ethical behavior basic to Jewish life as well as to participation in contemporary society. Genuine concern for the welfare of others, observance of mitzvos, love of the Jewish people, and pride in our Jewish heritage and values should characterize the intellectual goals and the daily behavior of our talmidim. -

A Resource Guide to Literature, Poetry, Art, Music & Videos by Holocaust

Bearing Witness BEARING WITNESS A Resource Guide to Literature, Poetry, Art, Music, and Videos by Holocaust Victims and Survivors PHILIP ROSEN and NINA APFELBAUM Greenwood Press Westport, Connecticut ● London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rosen, Philip. Bearing witness : a resource guide to literature, poetry, art, music, and videos by Holocaust victims and survivors / Philip Rosen and Nina Apfelbaum. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index. ISBN 0–313–31076–9 (alk. paper) 1. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945)—Personal narratives—Bio-bibliography. 2. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945), in literature—Bio-bibliography. 3. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945), in art—Catalogs. 4. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945)—Songs and music—Bibliography—Catalogs. 5. Holocaust,Jewish (1939–1945)—Video catalogs. I. Apfelbaum, Nina. II. Title. Z6374.H6 R67 2002 [D804.3] 016.94053’18—dc21 00–069153 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright ᭧ 2002 by Philip Rosen and Nina Apfelbaum All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 00–069153 ISBN: 0–313–31076–9 First published in 2002 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America TM The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 Contents Preface vii Historical Background of the Holocaust xi 1 Memoirs, Diaries, and Fiction of the Holocaust 1 2 Poetry of the Holocaust 105 3 Art of the Holocaust 121 4 Music of the Holocaust 165 5 Videos of the Holocaust Experience 183 Index 197 Preface The writers, artists, and musicians whose works are profiled in this re- source guide were selected on the basis of a number of criteria. -

A Fresh Perspective on the History of Hasidic Judaism

eSharp Issue 20: New Horizons A Fresh Perspective on the History of Hasidic Judaism Eva van Loenen (University of Southampton) Introduction In this article, I shall examine the history of Hasidic Judaism, a mystical,1 ultra-orthodox2 branch of Judaism, which values joyfully worshipping God’s presence in nature as highly as the strict observance of the laws of Torah3 and Talmud.4 In spite of being understudied, the history of Hasidic Judaism has divided historians until today. Indeed, Hasidic Jewish history is not one monolithic, clear-cut, straightforward chronicle. Rather, each scholar has created his own narrative and each one is as different as its author. While a brief introduction such as this cannot enter into all the myriad divergences and similarities between these stories, what I will attempt to do here is to incorporate and compare an array of different views in order to summarise the history of Hasidism and provide a more objective analysis, which has not yet been undertaken. Furthermore, my historical introduction in Hasidic Judaism will exemplify how mystical branches of mainstream religions might develop and shed light on an under-researched division of Judaism. The main focus of 1 Mystical movements strive for a personal experience of God or of his presence and values intuitive, spiritual insight or revelationary knowledge. The knowledge gained is generally ‘esoteric’ (‘within’ or hidden), leading to the term ‘esotericism’ as opposed to exoteric, based on the external reality which can be attested by anyone. 2 Ultra-orthodox Jews adhere most strictly to Jewish law as the holy word of God, delivered perfectly and completely to Moses on Mount Sinai. -

The 5 Towns Jewish Times Arab Terrorist Who Was Later Identified Lists of People Who Were Clients of Paper

$1.00 WWW.5TJT.COM VOL. 8 NO. 32 27 NISAN 5768 ohause ,arp MAY 2, 2008 INSIDE FROM THE EDITOR’S DESK DEAL OR NO DEAL? Welcome Back, Pilgrims BY LARRY GORDON Hannah Reich Berman 26 MindBiz Reading Kahane Esther Mann, LMSW 31 He was a solitary, heroic, School-Board Strategy PhotoByIvanH.Norman Larry Gordon 42 and tragic figure all wrapped up in one unassuming man Leaving A Legacy with a towering conscience. James C. Schneider 67 He was a man who could not be still or rest if Jews anywhere The traditional halachic sale of chametz for parts of the Five Towns and Far Five Towners In Israel in the world were not being Toby Klein Greenwald 75 Rockaway took place prior to Passover, at which time rabbis represented their afforded the same opportuni- congregants in a sale of their chametz (leavened products) to a non-Jew so ties available to those of us liv- that the products are not in the possession of Jews during the holiday. ing in freedom. As a result, After the conclusion of the holiday, the items are transferred back to their original owners. there was very little time for Pictured above (L–R): Rabbi Yisroel Meir Blumenkrantz, Rabbi Shaul Chill, Rabbi Dov Bressler, Duke Walters (to whom the chametz was sold), Rabbi Continued on Page 8 Rabbi Meir Kahane, a’h Yitzchok Frankel, and Rabbi Pinchas Chatzinoff. A GLIMPSE OF GREATNESS HEARD IN THE BAGEL STORE Part 2 and her grandparents would Inside The Bubble B Y RABBI be severed at her generation. -

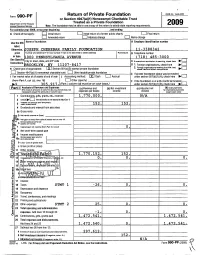

Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1 545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2009 I n t ernal R evenue Service Note . The foundation may be able to use a cony of this return to satisfy state reoortmo reaulrements. For calendar year 2009 , or tax year beginning , and ending G Check all that apply. Initial return 0 Initial return of a former public charity 0 Final return Amended return Address chanae 0 Name chanae Name of foundation A Employer identification number Use the IRS label. Otherwise , JOSEPH CHEHEBAR FAMILY FOUNDATION 11-3388342 print Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number ortype . 1000 PENNSYLVANIA AVENUE ( 718 ) 485-3000 See Specific City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending , check here ^ Instructions. BROOKLYN , NY 11207-8417 D I. Foreign organizations, check here 2. meeting s% test, H Check type of organization: ® Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation =are comp on 0 Section 4947(a )( 1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust 0 Other taxable private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: ® Cash 0 Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part Il, col (c), line 16) 1 Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month terminatio n 10- s 3 0 5 917. (Part 1, column (d) must be on cash basis.) under section 507( b )( 1 ) B), check here Part I Analysis of Revenue and Expenses (a) Revenue and (b ) Net investment (c) Adjusted net ( d) Disbursements (The total of amounts in columns (b). -

Community in Exile: German Jewish Identity Development in Wartime Shanghai, 1938-1945 Alice I

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2011 Community in Exile: German Jewish Identity Development in Wartime Shanghai, 1938-1945 Alice I. Reichman Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Reichman, Alice I., "Community in Exile: German Jewish Identity Development in Wartime Shanghai, 1938-1945" (2011). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 96. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/96 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE COMMUNITY IN EXILE: GERMAN JEWISH IDENTITY DEVELOPMENT IN WARTIME SHANGHAI, 1938-1945 SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR ARTHUR ROSENBAUM AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY ALICE REICHMAN FOR SENIOR THESIS ACADEMIC YEAR 2010-2011 APRIL 25, 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ……………………………………………………………………... iii INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………………………………....1 CHAPTER ONE FLIGHT FROM THE NAZIS AND ARRIVAL IN A FOREIGN LAND ……………………………....7 CHAPTER TWO LIFE AND CONDITIONS IN SHANGHAI ………………………………………………….......22 CHAPTER THREE RESPONDING TO LIFE IN SHANGHAI ……………………………………………………….38 CHAPTER FOUR A HETEROGENEOUS COMMUNITY : DIFFERENCES AMONG JEWISH REFUGEES ……………. 49 CHAPTER FIVE MAINTAINING A CENTRAL EUROPEAN IDENTITY : GERMANIC CULTURE COMES TO SHANGHAI ………………………………………………………………………………... 64 CHAPTER SIX YOUTH EXPERIENCE …………………………………………………………………….... 80 CHAPTER SEVEN A COSMOPOLITAN CITY : ENCOUNTERS AND EXCHANGES WITH OTHER CULTURES ……....98 CONCLUSION ………………………………………………………………………….... 108 DIRECTORY OF REFERENCED SURVIVORS ………………………………………………. 112 BIBLIOGRAPHY ………………………………………………………………………….. 117 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would first like to thank my reader, Professor Arthur Rosenbaum, for all the help that he has given me throughout this process. Without his guidance this thesis would not have been possible. I am grateful for how understanding and supportive he was throughout this stressful year. -

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Open Jerusalem Edited by Vincent Lemire (Paris-Est Marne-la-Vallée University) and Angelos Dalachanis (French School at Athens) VOLUME 1 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/opje Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Opening New Archives, Revisiting a Global City Edited by Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire LEIDEN | BOSTON Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing CC-BY-NC-ND License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. The Open Jerusalem project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) (starting grant No 337895) Note for the cover image: Photograph of two women making Palestinian point lace seated outdoors on a balcony, with the Old City of Jerusalem in the background. American Colony School of Handicrafts, Jerusalem, Palestine, ca. 1930. G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection, Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/mamcol.054/ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Dalachanis, Angelos, editor. -

Refugees and Relief: the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and European Jews in Cuba and Shanghai 1938-1943

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2015 Refugees And Relief: The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee And European Jews In Cuba And Shanghai 1938-1943 Zhava Litvac Glaser Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/561 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] REFUGEES AND RELIEF: THE AMERICAN JEWISH JOINT DISTRIBUTION COMMITTEE AND EUROPEAN JEWS IN CUBA AND SHANGHAI 1938-1943 by ZHAVA LITVAC GLASER A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the reQuirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2015 ii © 2015 ZHAVA LITVAC GLASER All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation reQuirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dagmar Herzog ________________________ _________________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Prof. Helena Rosenblatt ________________________ _________________________________________ Date Executive Officer Prof. Jane S. Gerber Prof. Atina Grossmann Prof. Benjamin C. Hett Prof. Robert M. Seltzer Supervisory Committee The City University of -

2018-YOSS-Advancing.Pdf

YOSS Advancing Winter 2018 Rav Binyamin Kamenetzky zt”l LEGACY CAMPAIGN Honoring the memory and impact of our founding Rosh Yeshiva, a visionary leader ...................................... Page 6 MENAHEL SPOTLIGHT A conversation with Rabbi Robinson and Rabbi Davidowitz ....................................... Page 3 REMEMBERING RAV BINYAMIN With warmth & dedication, he built a thriving Yeshiva and community .......................... Page 4 YOSS MEMORABLE MOMENTS Sharing the excitement .......................... Page 10 PAGE 2 MESSAGE FROM THE ROSH YESHIVA Sefer Shemos is the story of the emergence of Klal Yisrael from a small tribe of the progeny of Yaakov, to a thriving nation with millions of descendants, who accepted upon themselves the yoke of Torah. It is the story of a nation that went out to a desert and sowed the seeds of the future – a future that thrives to this very day. More than sixty years ago, my grandfather Rav Yaakov Kamenetzky, zt”l, charged my father and mother with the formidable task, “Go to the desert and plant the seeds of Torah.” What started as a fledgling school with six or seven boys, flourished more than a hundred fold. With institutions of tefilah, and higher Torah learning, all the outgrowth of that initial foray into the desert, my father’s impact is not only eternal but ever-expanding. This year’s dinner will mark both the commemoration of those accomplishments and a commitment to the renewal, refurbishment and expansion of the Torah facility he built brick by brick in 1964. Whether you are a student, an alumnus, a parent or community member, my father’s vision touched your life, and I hope that you will join us in honoring his. -

Till Death Do Us Part: the Halachic Prospects of Marriage for Conjoined (Siamese) Twins

259 ‘Till Death Do Us Part: The Halachic Prospects of Marriage for Conjoined (Siamese) Twins By: REUVEN CHAIM KLEIN There are many unknowns when it comes to discussions about Siamese twins. We do not know what causes the phenomenon of conjoined twins,1 we do not know what process determines how the twins will be conjoined, and we do not know why they are more common in girls than in boys. Why are thoracopagical twins (who are joined at the chest) the most com- mon type of conjoinment making up 75% of cases of Siamese twins,2 while craniopagus twins (who are connected at the head) are less com- mon? When it comes to integrating conjoined twins into greater society, an- other bevy of unknowns is unleashed: Are they one person or two? Could they get married?3 Can they be liable for corporal/capital punishment? Contemporary thought may have difficulty answering these questions, es- pecially the last three, which are not empirical inquiries. Fortunately, in 1 R. Yisroel Yehoshua Trunk of Kutna (1820–1893) claims that Jacob and Esau gestated within a shared amniotic sac in the womb of their mother Rebecca (as evidenced from the fact that Jacob came out grasping his older brother’s heel). As a result, there was a high risk that the twins would end up sticking together and developing as conjoined twins. In order to counter that possibility, G-d mi- raculously arranged for the twins to restlessly “run around” inside their mother’s womb (Gen. 25:22) in order that the two fetuses not stick together. -

Knights for Israel Honored at Camera Gala 2018 a Must-See Film

Editorials ..................................... 4A Op-Ed .......................................... 5A Calendar ...................................... 6A Scene Around ............................. 9A Synagogue Directory ................ 11A JTA News Briefs ........................ 13A WWW.HERITAGEFL.COM YEAR 42, NO. 40 JUNE 8, 2018 25 SIVAN, 5778 ORLANDO, FLORIDA SINGLE COPY 75¢ JNF’s Plant Your Way website NEW YORK—Jewish Na- it can be applied to any Jewish tional Fund revealed its new National Fund trip and the Plant Your Way website that Alexander Muss High School easily allows individuals to in Israel (AMHSI-JNF) is a raise money for a future trip huge bonus because donors to Israel while helping build can take advantage of the 100 the land of Israel. percent tax deductible status First introduced in 2000, of the contributions.” Plant Your Way has allowed Some of the benefits in- many hundreds of young clude: people a personal fundraising • Donations are 100 percent platform to raise money for a tax deductible; trip to Israel while giving back • It’s a great way to teach at the same time. Over the children and young adults the last 18 years, more than $1.3 basics of fundraising, while million has been generated for they build a connection to Jewish National Fund proj- Israel and plan a personal trip Knights for Israel members (l-r): Emily Aspinwall, Sam Busey, Jake Suster, Jesse Benjamin Slomowitz and Benji ects, typically by high school to Israel; Osterman, accepted the David Bar-Ilan Award for Outstanding Campus Activism. students. The new platform • Funds raised can be ap- allows parents/grandparents plied to any Israel trip (up to along with family, friends, age 30); coworkers and classmates • Participant can designate Knights for Israel honored to open Plant Your Way ac- to any of Jewish National counts for individuals from Fund’s seven program areas, birth up to the age of 30, and including forestry and green at Camera Gala 2018 for schools to raise money for innovation, water solutions, trips as well.