Downloading and Pirating of Dvds Throughout the Regions, Again a Strategy Typically Used by Hollywood Majors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Film, Media & Theatre Dissertations School of Film, Media & Theatre Spring 5-6-2019 Dynamics of a Periphery TV Industry: Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats Soo keung Jung [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_dissertations Recommended Citation Jung, Soo keung, "Dynamics of a Periphery TV Industry: Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2019. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_dissertations/7 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Film, Media & Theatre at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film, Media & Theatre Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DYNAMICS OF A PERIPHERY TV INDUSTRY: BIRTH AND EVOLUTION OF KOREAN REALITY SHOW FORMATS by SOOKEUNG JUNG Under the Direction of Ethan Tussey and Sharon Shahaf, PhD ABSTRACT Television format, a tradable program package, has allowed Korean television the new opportunity to be recognized globally. The booming transnational production of Korean reality formats have transformed the production culture, aesthetics and structure of the local television. This study, using a historical and practical approach to the evolution of the Korean reality formats, examines the dynamic relations between producer, industry and text in the -

D2492609215cd311123628ab69

Acknowledgements Publisher AN Cheongsook, Chairperson of KOFIC 206-46, Cheongnyangni-dong, Dongdaemun-gu. Seoul, Korea (130-010) Editor in Chief Daniel D. H. PARK, Director of International Promotion Department Editors KIM YeonSoo, Hyun-chang JUNG English Translators KIM YeonSoo, Darcy PAQUET Collaborators HUH Kyoung, KANG Byeong-woon, Darcy PAQUET Contributing Writer MOON Seok Cover and Book Design Design KongKam Film image and still photographs are provided by directors, producers, production & sales companies, JIFF (Jeonju International Film Festival), GIFF (Gwangju International Film Festival) and KIFV (The Association of Korean Independent Film & Video). Korean Film Council (KOFIC), December 2005 Korean Cinema 2005 Contents Foreword 04 A Review of Korean Cinema in 2005 06 Korean Film Council 12 Feature Films 20 Fiction 22 Animation 218 Documentary 224 Feature / Middle Length 226 Short 248 Short Films 258 Fiction 260 Animation 320 Films in Production 356 Appendix 386 Statistics 388 Index of 2005 Films 402 Addresses 412 Foreword The year 2005 saw the continued solid and sound prosperity of Korean films, both in terms of the domestic and international arenas, as well as industrial and artistic aspects. As of November, the market share for Korean films in the domestic market stood at 55 percent, which indicates that the yearly market share of Korean films will be over 50 percent for the third year in a row. In the international arena as well, Korean films were invited to major international film festivals including Cannes, Berlin, Venice, Locarno, and San Sebastian and received a warm reception from critics and audiences. It is often said that the current prosperity of Korean cinema is due to the strong commitment and policies introduced by the KIM Dae-joong government in 1999 to promote Korean films. -

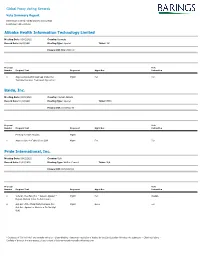

Global Proxy Voting Records

Global Proxy Voting Records Vote Summary Report Date range covered: 03/01/2021 to 03/31/2021 Location(s): All Locations Alibaba Health Information Technology Limited Meeting Date: 03/01/2021 Country: Bermuda Record Date: 02/23/2021 Meeting Type: Special Ticker: 241 Primary ISIN: BMG0171K1018 Proposal Vote Number Proposal Text Proponent Mgmt Rec Instruction 1 Approve Revised Annual Cap Under the Mgmt For For Technical Services Framework Agreement Baidu, Inc. Meeting Date: 03/01/2021 Country: Cayman Islands Record Date: 01/28/2021 Meeting Type: Special Ticker: BIDU Primary ISIN: US0567521085 Proposal Vote Number Proposal Text Proponent Mgmt Rec Instruction Meeting for ADR Holders Mgmt 1 Approve One-to-Eighty Stock Split Mgmt For For Pride International, Inc. Meeting Date: 03/01/2021 Country: USA Record Date: 12/01/2020 Meeting Type: Written Consent Ticker: N/A Primary ISIN: US74153QAJ13 Proposal Vote Number Proposal Text Proponent Mgmt Rec Instruction 1 Vote On The Plan (For = Accept, Against = Mgmt For Abstain Reject; Abstain Votes Do Not Count) 2 Opt Out of the Third-Party Releases (For = Mgmt None For Opt Out, Against or Abstain = Do Not Opt Out) * Instances of "Do Not Vote" are normally owing to: - Share-blocking - temporary restriction of trading by the Sub-Custodian following vote submission - Client restrictions - Conflicts of Interest. For any queries, please contact [email protected] Global Proxy Voting Records Vote Summary Report Date range covered: 03/01/2021 to 03/31/2021 Location(s): All Locations The -

Power of the Korean Film Producer: Park Chung Hee’S Forgotten Film Cartel of the 1960S Golden Decade and Its Legacy

Volume 10 | Issue 52 | Number 3 | Article ID 3875 | Dec 24, 2012 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Power of the Korean Film Producer: Park Chung Hee’s Forgotten Film Cartel of the 1960s Golden Decade and its Legacy Brian Yecies, Ae-Gyung Shim An analysis of the tactics adopted by the industry reveals the ways in which producers Key words: Korean cinema, filmnegotiated policy demands and contributed to production, film policy, Park Chung Hee, an industry “boom” – the likes of which were Shin Sang-ok not seen again until the late 1990s. After censorship was eliminated in 1996, a new Power of the Producer breed of writer-directors created a canon of internationally provocative and visuallySince the early 1990s, Korean film producers stunning genre-bending hit films, and new and have been shaping the local film industry in a established producers infused unprecedented variety of ways that diverge from those venture capital into the local industry. Today, a followed in the past. A slew of savvy producers bevy of key producers, including vertically and large production companies have aimed to integrated Korean conglomerates, maintain produce domestic hits as well as films for and dominance over the film industry whilewith Hollywood, China, and beyond, thus 2 engaging in a variety of relatively near-leading the industry to scale new heights. They transparent domestic and internationaldiffer markedly from those producers and companies that, throughout the 1970s and expansion strategies. Backing hits at home as 1980s, were primarily focused on profiting well as collaborating with filmmakers in China from the importation, distribution and and Hollywood have become priorities. -

New Paradigm in Cinema Industry CJ 4DX : What Is 4DX?

4DX’s Challenge for Global Hallyu Creation Presenter: Byung-Hwan Choi CEO / CJ 4DPLEX Hallyu, at the Extension Stage 1980s 1990s 2000~ Cultural Hong Kong Japan Korea Trend In Asia Hong Kong Noir Movies Manga, Games, J-Pops Soap Operas, K-Pops, Games, Movies… Initial Before Hallyu stage Leaping Stage Extension Stage Revenue $Bil What is “Hallyu”? Highest Profit 1.2 Hallyu, the Korean Wave, is a Record neologism referring to the increase in the worldwide popularity of 1.0 <Dae Jang Geum> South Korean culture. First Hallyu 0.8 Culture 0.6 Export Culture Import Psy, 0.4 H.O.T Heyday of K-Pop debut in China 0.2 1980 1984 1988 1992 1996 2000 2004 2008 2012 Source: SERI Report (June 19, 2013) 1 CJ, Korea’s Leading Culture Creator CJ’s Hallyu Philosophy as Global Lifestyle company : 3 2 CJ Group, Business Portfolio Global CJ Foodville Global Bio Production Global CJ O Shopping Global CGV 184 stores in 10 countries Brazil, China, Indonesia, China, Indian, Japan, USA, China, Vietnam, Global bibigo Malaysia, USA Philippines, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia USA, China, UK, Japan, Turkey, Vietnam Singapore, Indonesia 3 CJ Group, Business Portfolio Sales by Year ($ Bil) 2013 9.2 2012 8.9 2011 8.2 2010 6.9 Weight of overseas sales as % of total sales 4 CJ Group, Business Portfolio Sales by Year ($ Bil) 2017 (exp) 5.0 2012 1.8 2011 1.5 2010 1.2 5 CJ Group, Business Portfolio CJ O Shopping Sales by Year ($ Bil) 2013 2.7 2012 2.5 2011 2.3 2010 1.8 CJ Korea Express CJ O SHOPPING GLOBAL BUSINESS 6 CJ Group, Business Portfolio PR Value from CJ’s Hallyu festivals - MAMA (Mnet Asia Music Awards) 2013 = 2.6 Bil - KCON 2014 = 36 Mil CJ E&M Sales by Year ($ Bil) 2013 1.6 2012 1.3 2011 1.2 CJ CGV & HelloVision Sales by Year ($ Bil) 2013 1.9 2012 1.5 2011 1.2 7 At the Center of Global Movie Industry Global Trends in Movie Industry Global Cinema Industry In Korea, cinema box office and attendance is continuously increasing since 2010. -

Published 26 February 2019 LKFF 2018

1–25 NOVEMBER LONSM_350_ .pdf 1 2018. 8. 22. �� 8:48 It is my pleasure to introduce to you the 13th instalment of the London Korean Film Festival, our annual celebration of Korean Film in all its forms. Since 2006, the Korean Cultural Centre UK has presented the festival with two simple goals, namely to be the most inclusive festival of national cinema anywhere and to always improve on where we left off. As part of this goal Daily to Seoul and Beyond for greater inclusivity, in 2016 the main direction of the festival was tweaked to allow a broader, more diverse range of Korean films to be shown. With special themes exploring different subjects, the popular strands covering everything from box office hits to Korean classics, as well as monthly teaser screenings, the festival has continued to find new audiences for Korean cinema. This year the festival once again works with critics, academics and visiting programmers on each strand of the festival and has partnered with several university film departments as well. At the time of writing, this year’s festival will screen upwards of 55 films, with a special focus entitled ‘A Slice of Everyday Life’. This will include the opening and closing films, Microhabitat by Jeon Go-woon, and The Return by Malene Choi. C ‘A Slice of Everyday Life’ explores valuable snapshots of the sometimes-ignored M lives of ordinary Koreans, often fragile individuals on the edge of society. One Y will also see director Lee Myung-se's films in the Contemporary Classics strand and Park Kiyong's films in the Indie Firepower strand. -

The Next Growth Strategy for Hallyu 79

Lee & Kim / The Next Growth Strategy for Hallyu 79 THE NEXT GROWTH STRATEGY FOR HALLYU A Comparative Analysis of Global Entertainment Firms Yeon W. Lee Seoul School of Integrated Science and Technology [email protected] Kyuchan Kim Korea Culture and Tourism Institute [email protected] Abstract Previous policy approaches on Hallyu have been focused on the role of government engagement, particularly in fostering diversity and equal business opportunities for small-and-medium enterprises (SMEs). However, a more strategic approach to the cultural industries should be implemented by carefully examining the role of the private sector, particularly the role of large enterprises (LEs). his is important because LEs have an overarching and fundamentally diferentiated role in increasing the size of industry through their expansive value-creating activities and diversiied business areas. his study focuses on the complementary roles of SMEs and LEs in facilitating the growth of Hallyu by bringing in the perspective of value chain diversiication and the modiied value chain framework for the ilm industry. By conducting a comparative analysis of the global entertainment irms in the US, China, and Japan, this study reveals how LEs in the global market enter and explore new industries within culture and continue to enhance their competitiveness. By forming a business ecosystem through linking their value-creating activities as the platform of network, this study looks into the synergistic role among enterprises of diferent size and scale and suggests that Korea’s policy for Hallyu should reorient toward a new growth strategy that encourages the integrative network of irms where the value activities of LEs serve as the platform for convergence. -

Cj Logistics Sustainability Report 2018-2019

CJ LOGISTICS SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2018-2019 REPORT SUSTAINABILITY LOGISTICS CJ This report is printed on FSC™(Forest Stewardship Council) Certified paper with soy ink. CJ LOGISTICS SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2018-2019 FORWARDING & INTERNATIONAL EXPRESS STEVEDORING & TRANSPORTATION CONTRACT LOGISTICS PROJECT LOGISTICS PARCEL www.cjlogistics.com ABOUT THIS REPORT CONTENTS 04 CEO Message SUSTAINABILITY AROUND THE GLOBE 54 USA Summary BUSINESS OVERVIEW 56 China CJ Logistics publishes a sustainable management report each year to 08 CJ Management Philosophy 58 India transparently disclose its economic, social, and environmental activities 09 About Us 60 Vietnam and achievements. We plan to publish a sustainable management report every year as a communication tool for stakeholders to reflect 11 Our Business 62 Others and maintain steady growth. 18 Global Network SUSTAINABILITY MANAGEMENT Reporting Period and Scope SUSTAINABILITY ISSUES 66 Corporate Governance This is a report on the key sustainable management performance 22 Business Performance 68 Risk Management during the period between January 1, 2018 to June 30, 2019. It includes 28 Safety and Health 70 Customer Satisfaction quantitative performance data from the most recent three years or 34 Environmental Management 72 Information Security more to identify trends. Some important information include details 74 Compliance from up to the second half of 2019 to facilitate your understanding. The SUSTAINABILITY FUNDAMENTALS 76 Human Rights report covers all work sites of CJ Logistics in Korea. Some information 77 Stakeholder Engagement from overseas work sites are also included. 40 Employees 78 Materiality Assessment 45 Partners 80 UN SDGs Report Preparation Standards 48 Community This report has been prepared in accordance with the Core Option of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) Standards, which is a standard for international reporting of sustainable management. -

CJ Corporation (001040 KS) BUY (Upgrade)

EQUITYEQUITY RESEARCH RESEARCH 5 Mar 2008 CJ (001040 KS) CJ Corporation (001040 KS) BUY (Upgrade) Waiting for positive signals as it converts to a holding company Patrick Kim (82-2-769-3809) [email protected] Upgrade to BUY, and boost TP to W120,000 We have a BUY rating on CJ Corporation (CJ), setting our target price at W120,000. Based Share price (Mar 5) W73,300 on our sum-of-parts valuation we derived our target price by adding the per share stake value Six-month TP W120,000 of W131,650 to the per share tangible asset value of W5,080, and then deducting W16,260 Par value W5,000 per share in borrowings. KOSPI 1,676.18 52 week high/low W147,968/W64,000 It has been half a year since it converted to a holding company structure Capital stock In Sep 2007, CJ began to convert to a holding company with a subsidiary spin-off. Then in W137.7bn (Common stock) Dec 2007, as it completed a tender offer for shares of CJ CheilJedang, CJ emerged as an Market cap W2,062.6bn undisputed holding company. As such, the company is comprised of a total of 15 subsidiaries, Foreign ownership 15.5% including three food production and food service companies, five E&M (Entertainment & Performance (%) Absolute Relative Media) companies, three new retail businesses, and three companies working in either the 1 m 0.4 1.3 financial industry or the infrastructure industry. Meanwhile, it has six listed subsidiaries and 6 m -11.5 1.3 nine unlisted ones. -

Cultural Production in Transnational Culture: an Analysis of Cultural Creators in the Korean Wave

International Journal of Communication 15(2021), 1810–1835 1932–8036/20210005 Cultural Production in Transnational Culture: An Analysis of Cultural Creators in the Korean Wave DAL YONG JIN1 Simon Fraser University, Canada By employing cultural production approaches in conjunction with the global cultural economy, this article attempts to determine the primary characteristics of the rapid growth of local cultural industries and the global penetration of Korean cultural content. It documents major creators and their products that are received in many countries to identify who they are and what the major cultural products are. It also investigates power relations between cultural creators and the surrounding sociocultural and political milieu, discussing how cultural creators develop local popular culture toward the global cultural markets. I found that cultural creators emphasize the importance of cultural identity to appeal to global audiences as well as local audiences instead of emphasizing solely hybridization. Keywords: cultural production, Hallyu, cultural creators, transnational culture Since the early 2010s, the Korean Wave (Hallyu in Korean) has become globally popular, and media scholars (Han, 2017; T. J. Yoon & Kang, 2017) have paid attention to the recent growth of Hallyu in many parts of the world. Although the influence of Western culture has continued in the Korean cultural market as well as elsewhere, local cultural industries have expanded the exportation of their popular culture to several regions in both the Global South and the Global North. Social media have especially played a major role in disseminating Korean culture (Huang, 2017; Jin & Yoon, 2016), and Korean popular culture is arguably reaching almost every corner of the world. -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

Membership Specials INCLUDING Mccartney Dylan Crosby, Stills and Nash and MORE!

MARCH 2014 ALL- NEW LINEUP OF Membership Specials INCLUDING McCartney Dylan Crosby, Stills and Nash AND MORE! Edie Brickell and Steve Martin The Monthly Magazine for Members of Vegas PBS Contents LetterFROM THE GENERAL MANAGER Cover Story An All-New Lineup of Membership Specials 6 March truly comes in like a lion this year with an incredible lineup of new programs during our spring membership campaign. March Program Highlights Departments his month, Vegas PBS kicks off the first membership cam- Message to Our Members 5 paign of the new year with a lineup of specials from well- Letter from General Manager Tom Axtell known experts. Viewers will travel ancient Italian cities with Rick Steves, hear about financial strategies from Suze Orman, School Media 9 and explore life’s guiding principles with Dr. Wayne Dyer. Planned Giving 17 MusicT lovers will enjoy two new concert specials from Great Performances, including a once-in-a-lifetime concert event celebrating Bob Dylan, and a unique look at the musical side of Steve Martin and his Features bluegrass band the Steep Canyon Rangers. You can sing along with your Can Eating Insects Save the World? 10 favorite artists like Paul McCartney, Il Divo, Andrea Bocelli, the Bee Gees and Antiques Roadshow and Elvis, and discover new talent like Italian rock singer Zucchero and retro vocal group Under the Streetlamp, featuring Gentleman’s Rule. Women’s History Month 12 Vegas PBS also celebrates St. Patrick’s Day with a quest down Arts: American Masters: Lennon NYC 14 Ireland’s greatest geographical landmark in Nature: Ireland’s Wild River and charming Irish music in Celtic Woman: Emerald.