Non-Baryonic Dark Matter: Observational Evidence and Detection Methods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adrien Christian René THOB

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE MORPHOLOGY AND KINEMATICS OF GALAXIES AND ITS DEPENDENCE ON DARK MATTER HALO STRUCTURE IN SIMULATED GALAXIES Adrien Christian René THOB A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Liverpool John Moores University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 26 April 2019 To my grand-parents, René Roumeaux, Christian Thob, Yvette Roumeaux (née Bajaud) and Anne-Marie Thob (née Léglise). ii Abstract Galaxies are among nature’s most majestic and diverse structures. They can play host to as few as several thousands of stars, or as many as hundreds of billions. They exhibit a broad range of shapes, sizes, colours, and they can inhabit vastly differing cosmic environments. The physics of galaxy formation is highly non-linear and in- volves a variety of physical mechanisms, precluding the development of entirely an- alytic descriptions, thus requiring that theoretical ideas concerning the origin of this diversity are tested via the confrontation of numerical models (or “simulations”) with observational measurements. The EAGLE project (which stands for Evolution and Assembly of GaLaxies and their Environments) is a state-of-the-art suite of such cos- mological hydrodynamical simulations of the Universe. EAGLE is unique in that the ill-understood efficiencies of feedback mechanisms implemented in the model were calibrated to ensure that the observed stellar masses and sizes of present-day galaxies were reproduced. We investigate the connection between the morphology and internal 9:5 kinematics of the stellar component of central galaxies with mass M? > 10 M in the EAGLE simulations. We compare several kinematic diagnostics commonly used to describe simulated galaxies, and find good consistency between them. -

Letter of Interest Cosmic Probes of Ultra-Light Axion Dark Matter

Snowmass2021 - Letter of Interest Cosmic probes of ultra-light axion dark matter Thematic Areas: (check all that apply /) (CF1) Dark Matter: Particle Like (CF2) Dark Matter: Wavelike (CF3) Dark Matter: Cosmic Probes (CF4) Dark Energy and Cosmic Acceleration: The Modern Universe (CF5) Dark Energy and Cosmic Acceleration: Cosmic Dawn and Before (CF6) Dark Energy and Cosmic Acceleration: Complementarity of Probes and New Facilities (CF7) Cosmic Probes of Fundamental Physics (TF09) Astro-particle physics and cosmology Contact Information: Name (Institution) [email]: Keir K. Rogers (Oskar Klein Centre for Cosmoparticle Physics, Stockholm University; Dunlap Institute, University of Toronto) [ [email protected]] Authors: Simeon Bird (UC Riverside), Simon Birrer (Stanford University), Djuna Croon (TRIUMF), Alex Drlica-Wagner (Fermilab, University of Chicago), Jeff A. Dror (UC Berkeley, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory), Daniel Grin (Haverford College), David J. E. Marsh (Georg-August University Goettingen), Philip Mocz (Princeton), Ethan Nadler (Stanford), Chanda Prescod-Weinstein (University of New Hamp- shire), Keir K. Rogers (Oskar Klein Centre for Cosmoparticle Physics, Stockholm University; Dunlap Insti- tute, University of Toronto), Katelin Schutz (MIT), Neelima Sehgal (Stony Brook University), Yu-Dai Tsai (Fermilab), Tien-Tien Yu (University of Oregon), Yimin Zhong (University of Chicago). Abstract: Ultra-light axions are a compelling dark matter candidate, motivated by the string axiverse, the strong CP problem in QCD, and possible tensions in the CDM model. They are hard to probe experimentally, and so cosmological/astrophysical observations are very sensitive to the distinctive gravitational phenomena of ULA dark matter. There is the prospect of probing fifteen orders of magnitude in mass, often down to sub-percent contributions to the DM in the next ten to twenty years. -

Particle Dark Matter an Introduction Into Evidence, Models, and Direct Searches

Particle Dark Matter An Introduction into Evidence, Models, and Direct Searches Lecture for ESIPAP 2016 European School of Instrumentation in Particle & Astroparticle Physics Archamps Technopole XENON1T January 25th, 2016 Uwe Oberlack Institute of Physics & PRISMA Cluster of Excellence Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz http://xenon.physik.uni-mainz.de Outline ● Evidence for Dark Matter: ▸ The Problem of Missing Mass ▸ In galaxies ▸ In galaxy clusters ▸ In the universe as a whole ● DM Candidates: ▸ The DM particle zoo ▸ WIMPs ● DM Direct Searches: ▸ Detection principle, physics inputs ▸ Example experiments & results ▸ Outlook Uwe Oberlack ESIPAP 2016 2 Types of Evidences for Dark Matter ● Kinematic studies use luminous astrophysical objects to probe the gravitational potential of a massive environment, e.g.: ▸ Stars or gas clouds probing the gravitational potential of galaxies ▸ Galaxies or intergalactic gas probing the gravitational potential of galaxy clusters ● Gravitational lensing is an independent way to measure the total mass (profle) of a foreground object using the light of background sources (galaxies, active galactic nuclei). ● Comparison of mass profles with observed luminosity profles lead to a problem of missing mass, usually interpreted as evidence for Dark Matter. ● Measuring the geometry (curvature) of the universe, indicates a ”fat” universe with close to critical density. Comparison with luminous mass: → a major accounting problem! Including observations of the expansion history lead to the Standard Model of Cosmology: accounting defcit solved by ~68% Dark Energy, ~27% Dark Matter and <5% “regular” (baryonic) matter. ● Other lines of evidence probe properties of matter under the infuence of gravity: ▸ the equation of state of oscillating matter as observed through fuctuations of the Cosmic Microwave Background (acoustic peaks). -

Mixed Axion/Neutralino Cold Dark Matter in Supersymmetric Models

Preprint typeset in JHEP style - HYPER VERSION Mixed axion/neutralino cold dark matter in supersymmetric models Howard Baera, Andre Lessaa, Shibi Rajagopalana,b and Warintorn Sreethawonga aDept. of Physics and Astronomy, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK 73019, USA bLaboratoire de Physique Subatomique et de Cosmologie, UJF Grenoble 1, CNRS/IN2P3, INPG, 53 Avenue des Martyrs, F-38026 Grenoble, France E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected],[email protected] Abstract: We consider supersymmetric (SUSY) models wherein the strong CP problem is solved by the Peccei-Quinn (PQ) mechanism with a concommitant axion/axino supermul- tiplet. We examine R-parity conserving models where the neutralino is the lightest SUSY particle, so that a mixture of neutralinos and axions serve as cold dark matter (aZ1 CDM). The mixed aZ1 CDM scenario can match the measured dark matter abundance for SUSY models which typically give too low a value of the usual thermal neutralino abundance,e such as modelse with wino-like or higgsino-like dark matter. The usual thermal neutralino abundance can be greatly enhanced by the decay of thermally-produced axinos (˜a) to neu- tralinos, followed by neutralino re-annihilation at temperatures much lower than freeze-out. In this case, the relic density is usually neutralino dominated, and goes as (f /N)/m3/2. ∼ a a˜ If axino decay occurs before neutralino freeze-out, then instead the neutralino abundance can be augmented by relic axions to match the measured abundance. Entropy production from late-time axino decays can diminish the axion abundance, but ultimately not the arXiv:1103.5413v1 [hep-ph] 28 Mar 2011 neutralino abundance. -

![DARK MATTER and NEUTRINOS Arxiv:1711.10564V1 [Physics.Pop-Ph]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1574/dark-matter-and-neutrinos-arxiv-1711-10564v1-physics-pop-ph-391574.webp)

DARK MATTER and NEUTRINOS Arxiv:1711.10564V1 [Physics.Pop-Ph]

Physics Education 1 dateline DARK MATTER AND NEUTRINOS Gazal Sharma1, Anu2 and B. C. Chauhan3 Department of Physics & Astronomical Science School of Physical & Material Sciences Central University of Himachal Pradesh (CUHP) Dharamshala, Kangra (HP) INDIA-176215. [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] (Submitted 03-08-2015) Abstract The Keplerian distribution of velocities is not observed in the rotation of large scale structures, such as found in the rotation of spiral galaxies. The deviation from Keplerian distribution provides compelling evidence of the presence of non-luminous matter i.e. called dark matter. There are several astrophysical motivations for investigating the dark matter in and around the galaxy as halo. In this work we address various theoretical and experimental indications pointing towards the existence of this unknown form of matter. Amongst its constituents neutrino is one of the most prospective candidates. We know the neutrinos oscillate and have tiny masses, but there are also signatures for existence of heavy and light sterile neutrinos and possibility of their mixing. Altogether, the role of neutrinos is of great interests in cosmology and understanding dark matter. arXiv:1711.10564v1 [physics.pop-ph] 23 Nov 2017 1 Introduction revealed in 2013 that our Universe contains 68:3% of dark energy, 26:8% of dark matter, and only 4:9% of the Universe is known mat- As a human being the biggest surprise for us ter which includes all the stars, planetary sys- was, that the Universe in which we live in tems, galaxies, and interstellar gas etc.. This is mostly dark. -

A Derivation of Modified Newtonian Dynamics

Journal of The Korean Astronomical Society http://dx.doi.org/10.5303/JKAS.2013.46.2.93 46: 93 ∼ 96, 2013 April ISSN:1225-4614 c 2013 The Korean Astronomical Society. All Rights Reserved. http://jkas.kas.org A DERIVATION OF MODIFIED NEWTONIAN DYNAMICS Sascha Trippe Department of Physics and Astronomy, Seoul National University, Seoul 151-742, Korea E-mail : [email protected] (Received February 14, 2013; Revised March 20, 2013; Accepted March 29, 2013) ABSTRACT Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND) is a possible solution for the missing mass problem in galac- tic dynamics; its predictions are in good agreement with observations in the limit of weak accelerations. However, MOND does not derive from a physical mechanism and does not make predictions on the transitional regime from Newtonian to modified dynamics; rather, empirical transition functions have to be constructed from the boundary conditions and comparisons with observations. I compare the formalism of classical MOND to the scaling law derived from a toy model of gravity based on virtual massive gravitons (the “graviton picture”) which I proposed recently. I conclude that MOND naturally derives from the “graviton picture” at least for the case of non-relativistic, highly symmetric dynamical systems. This suggests that – to first order – the “graviton picture” indeed provides a valid candidate for the physical mechanism behind MOND and gravity on galactic scales in general. Key words : Gravitation — Galaxies: kinematics and dynamics −10 −2 1. INTRODUCTION where x = ac/am, am ≈ 10 ms is Milgrom’s con- stant, and µ(x)isa transition function with the asymp- “ It is worth remembering that all of the discus- totic behavior µ(x) → 1 for x ≫ 1 and µ(x) → x for sion [on dark matter] so far has been based on x ≪ 1. -

WNPPC Program Booklet

58th Winter Nuclear & Particle Physics Virtual Conference WNPPC 2021 February 9-12 2021 WNPPC.TRIUMF.CA Book of Abstracts 58th WINTER NUCLEAR AND PARTICLE PHYSICS CONFERENCE WNPPC 2021 Virtual Online Conference February 9 - 12, 2021 Organizing Committee Soud Al Kharusi . McGill Alain Bellerive . Carleton Thomas Brunner . current chair, McGill Jens Dilling . TRIUMF Beatrice Franke . future chair, TRIUMF Dana Giasson . TRIUMF Gwen Grinyer . Regina Blair Jamieson . past chair, Winnipeg Allayne McGowan . TRIUMF Tony Noble . Queen's Ken Ragan . McGill Hussain Rasiwala . McGill Jana Thomson . TRIUMF Andreas Warburton . McGill Hosted by McGill University and TRIUMF WNPPC j i Welcome to WNPPC 2021! On behalf of the organizing committee, I would like to welcome you to the 58th Winter Nuclear and Particle Physics Conference. As always, this year's conference brings to- gether scientists from the entire Canadian subatomic physics community and serves as an important venue for our junior scientists and researchers from across the country to network and socialize. Unlike previous conferences of this series, we will unfortunately not be able to meet in person this year. WNPPC 2021 will be a virtual online conference. A big part of WNPPC, besides all the excellent physics presentations, has been the opportunity to meet old friends and make new ones, and to discuss physics, talk about life, and develop our community. The social aspect of WNPPC has been one of the things that makes this conference so special and dear to many of us. Our goal in the organizing committee has been to keep this spirit alive this year despite being restricted to a virtual format, and provide ample opportunities to meet with peers, form new friendships, and enjoy each other's company. -

Axionyx: Simulating Mixed Fuzzy and Cold Dark Matter

AxioNyx: Simulating Mixed Fuzzy and Cold Dark Matter Bodo Schwabe,1, ∗ Mateja Gosenca,2, y Christoph Behrens,1, z Jens C. Niemeyer,1, 2, x and Richard Easther2, { 1Institut f¨urAstrophysik, Universit¨atG¨ottingen,Germany 2Department of Physics, University of Auckland, New Zealand (Dated: July 17, 2020) The distinctive effects of fuzzy dark matter are most visible at non-linear galactic scales. We present the first simulations of mixed fuzzy and cold dark matter, obtained with an extended version of the Nyx code. Fuzzy (or ultralight, or axion-like) dark matter dynamics are governed by the comoving Schr¨odinger-Poisson equation. This is evolved with a pseudospectral algorithm on the root grid, and with finite differencing at up to six levels of adaptive refinement. Cold dark matter is evolved with the existing N-body implementation in Nyx. We present the first investigations of spherical collapse in mixed dark matter models, focusing on radial density profiles, velocity spectra and soliton formation in collapsed halos. We find that the effective granule masses decrease in proportion to the fraction of fuzzy dark matter which quadratically suppresses soliton growth, and that a central soliton only forms if the fuzzy dark matter fraction is greater than 10%. The Nyx framework supports baryonic physics and key astrophysical processes such as star formation. Consequently, AxioNyx will enable increasingly realistic studies of fuzzy dark matter astrophysics. I. INTRODUCTION Small-scale differences open the possibility of observa- tional comparisons of FDM and CDM. Moreover, the ob- The physical nature of dark matter is a major open served small scale properties of galaxies may be in tension question for both astrophysics and particle physics. -

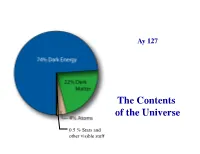

The Contents of the Universe

Ay 127! The Contents of the Universe 0.5 % Stars and other visible stuff Supernovae alone ⇒ Accelerating expansion ⇒ Λ > 0 CMB alone ⇒ Flat universe ⇒ Λ > 0 Any two of SN, CMB, LSS ⇒ Dark energy ~70% Also in agreement with the age estimates (globular clusters, nucleocosmochronology, white dwarfs) Today’s Best Guess Universe Age: Best fit CMB model - consistent with ages of oldest stars t0 =13.82 ± 0.05 Gyr Hubble constant: CMB + HST Key Project to -1 -1 measure Cepheid distances H0 = 69 km s Mpc € Density of ordinary matter: CMB + comparison of nucleosynthesis with Lyman-a Ωbaryon = 0.04 € forest deuterium measurement Density of all forms of matter: Cluster dark matter estimate CMB power spectrum 0.31 € Ωmatter = Cosmological constant: Supernova data, CMB evidence Ω = 0.69 for a flat universe plus a low € Λ matter density € The Component Densities at z ~ 0, in critical density units, assuming h ≈ 0.7 Total matter/energy density: Ω0,tot ≈ 1.00 From CMB, and consistent with SNe, LSS From local dynamics and LSS, and Matter density: Ω0,m ≈ 0.31 consistent with SNe, CMB From cosmic nucleosynthesis, Baryon density: Ω0,b ≈ 0.045 and independently from CMB Luminous baryon density: Ω0,lum ≈ 0.005 From the census of luminous matter (stars, gas) Since: Ω0,tot > Ω0,m > Ω0,b > Ω0,lum There is baryonic dark matter There is non-baryonic dark matter There is dark energy The Luminosity Density Integrate galaxy luminosity function (obtained from large redshift surveys) to obtain the mean luminosity density at z ~ 0 8 3 SDSS, r band: ρL = (1.8 ± 0.2) 10 h70 L/Mpc 8 3 2dFGRS, b band: ρL = (1.4 ± 0.2) 10 h70 L/Mpc Luminosity To Mass Typical (M/L) ratios in the B band along the Hubble sequence, within the luminous portions of galaxies, are ~ 4 - 5 M/L This includes some dark matter - for pure stellar populations, (M/L) ratios should be slightly lower. -

Modified Newtonian Dynamics, an Introductory Review

Modified Newtonian Dynamics, an Introductory Review Riccardo Scarpa European Southern Observatory, Chile E-mail [email protected] Abstract. By the time, in 1937, the Swiss astronomer Zwicky measured the velocity dispersion of the Coma cluster of galaxies, astronomers somehow got acquainted with the idea that the universe is filled by some kind of dark matter. After almost a century of investigations, we have learned two things about dark matter, (i) it has to be non-baryonic -- that is, made of something new that interact with normal matter only by gravitation-- and, (ii) that its effects are observed in -8 -2 stellar systems when and only when their internal acceleration of gravity falls below a fix value a0=1.2×10 cm s . Being completely decoupled dark and normal matter can mix in any ratio to form the objects we see in the universe, and indeed observations show the relative content of dark matter to vary dramatically from object to object. This is in open contrast with point (ii). In fact, there is no reason why normal and dark matter should conspire to mix in just the right way for the mass discrepancy to appear always below a fixed acceleration. This systematic, more than anything else, tells us we might be facing a failure of the law of gravity in the weak field limit rather then the effects of dark matter. Thus, in an attempt to avoid the need for dark matter many modifications of the law of gravity have been proposed in the past decades. The most successful – and the only one that survived observational tests -- is the Modified Newtonian Dynamics. -

History of Dark Matter

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) History of dark matter Bertone, G.; Hooper, D. DOI 10.1103/RevModPhys.90.045002 Publication date 2018 Document Version Final published version Published in Reviews of Modern Physics Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Bertone, G., & Hooper, D. (2018). History of dark matter. Reviews of Modern Physics, 90(4), [045002]. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.90.045002 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:25 Sep 2021 REVIEWS OF MODERN PHYSICS, VOLUME 90, OCTOBER–DECEMBER 2018 History of dark matter Gianfranco Bertone GRAPPA, University of Amsterdam, Science Park 904 1098XH Amsterdam, Netherlands Dan Hooper Center for Particle Astrophysics, Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, Batavia, Illinois 60510, USA and Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, The University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois 60637, USA (published 15 October 2018) Although dark matter is a central element of modern cosmology, the history of how it became accepted as part of the dominant paradigm is often ignored or condensed into an anecdotal account focused around the work of a few pioneering scientists. -

Arxiv:Astro-Ph/0508141V2 29 May 2006 O Opeeve H Edri Eerdt H Above the to Referred Is Reader the Case, Any View in Complete Reionization

Gravitino, Axino, Kaluza-Klein Graviton Warm and Mixed Dark Matter and Reionization Karsten Jedamzik a, Martin Lemoine b, Gilbert Moultaka a a Laboratoire de Physique Th´eorique et Astroparticules, CNRS UMR 5825, Universit´eMontpellier II, F-34095 Montpellier Cedex 5, France b GReCO, Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris, CNRS, 98 bis boulevard Arago, F-75014 Paris, France Stable particle dark matter may well originate during the decay of long-lived relic particles, as recently extensively examined in the cases of the axino, gravitino, and higher-dimensional Kaluza- Klein (KK) graviton. It is shown that in much of the viable parameter space such dark matter emerges naturally warm/hot or mixed. In particular, decay produced gravitinos (KK-gravitons) may only be considered cold for the mass of the decaying particle in the several TeV range, unless the decaying particle and the dark matter particle are almost degenerate. Such dark matter candidates are thus subject to a host of cosmological constraints on warm and mixed dark matter, such as limits from a proper reionization of the Universe, the Lyman-α forest, and the abundance of clusters of galaxies.. It is shown that constraints from an early reionsation epoch, such as indicated by recent observations, may potentially limit such warm/hot components to contribute only a very small fraction to the dark matter. The nature of the ubiquitous dark matter is still un- studies as well. known. Dark matter in form of fundamental, and as yet Decay produced particle dark matter is often experimentally undiscovered, stable particles predicted warm/hot, i.e. is endowed with primordial free-streaming to exist in extensions of the standard model of parti- velocities leading to the early erasure of small-scale per- cle physics may be particularly promising.