Adrien Christian René THOB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Particle Dark Matter an Introduction Into Evidence, Models, and Direct Searches

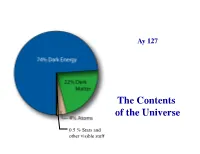

Particle Dark Matter An Introduction into Evidence, Models, and Direct Searches Lecture for ESIPAP 2016 European School of Instrumentation in Particle & Astroparticle Physics Archamps Technopole XENON1T January 25th, 2016 Uwe Oberlack Institute of Physics & PRISMA Cluster of Excellence Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz http://xenon.physik.uni-mainz.de Outline ● Evidence for Dark Matter: ▸ The Problem of Missing Mass ▸ In galaxies ▸ In galaxy clusters ▸ In the universe as a whole ● DM Candidates: ▸ The DM particle zoo ▸ WIMPs ● DM Direct Searches: ▸ Detection principle, physics inputs ▸ Example experiments & results ▸ Outlook Uwe Oberlack ESIPAP 2016 2 Types of Evidences for Dark Matter ● Kinematic studies use luminous astrophysical objects to probe the gravitational potential of a massive environment, e.g.: ▸ Stars or gas clouds probing the gravitational potential of galaxies ▸ Galaxies or intergalactic gas probing the gravitational potential of galaxy clusters ● Gravitational lensing is an independent way to measure the total mass (profle) of a foreground object using the light of background sources (galaxies, active galactic nuclei). ● Comparison of mass profles with observed luminosity profles lead to a problem of missing mass, usually interpreted as evidence for Dark Matter. ● Measuring the geometry (curvature) of the universe, indicates a ”fat” universe with close to critical density. Comparison with luminous mass: → a major accounting problem! Including observations of the expansion history lead to the Standard Model of Cosmology: accounting defcit solved by ~68% Dark Energy, ~27% Dark Matter and <5% “regular” (baryonic) matter. ● Other lines of evidence probe properties of matter under the infuence of gravity: ▸ the equation of state of oscillating matter as observed through fuctuations of the Cosmic Microwave Background (acoustic peaks). -

Dark Energy and Dark Matter

Dark Energy and Dark Matter Jeevan Regmi Department of Physics, Prithvi Narayan Campus, Pokhara [email protected] Abstract: The new discoveries and evidences in the field of astrophysics have explored new area of discussion each day. It provides an inspiration for the search of new laws and symmetries in nature. One of the interesting issues of the decade is the accelerating universe. Though much is known about universe, still a lot of mysteries are present about it. The new concepts of dark energy and dark matter are being explained to answer the mysterious facts. However it unfolds the rays of hope for solving the various properties and dimensions of space. Keywords: dark energy, dark matter, accelerating universe, space-time curvature, cosmological constant, gravitational lensing. 1. INTRODUCTION observations. Precision measurements of the cosmic It was Albert Einstein first to realize that empty microwave background (CMB) have shown that the space is not 'nothing'. Space has amazing properties. total energy density of the universe is very near the Many of which are just beginning to be understood. critical density needed to make the universe flat The first property that Einstein discovered is that it is (i.e. the curvature of space-time, defined in General possible for more space to come into existence. And Relativity, goes to zero on large scales). Since energy his cosmological constant makes a prediction that is equivalent to mass (Special Relativity: E = mc2), empty space can possess its own energy. Theorists this is usually expressed in terms of a critical mass still don't have correct explanation for this but they density needed to make the universe flat. -

![DARK MATTER and NEUTRINOS Arxiv:1711.10564V1 [Physics.Pop-Ph]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1574/dark-matter-and-neutrinos-arxiv-1711-10564v1-physics-pop-ph-391574.webp)

DARK MATTER and NEUTRINOS Arxiv:1711.10564V1 [Physics.Pop-Ph]

Physics Education 1 dateline DARK MATTER AND NEUTRINOS Gazal Sharma1, Anu2 and B. C. Chauhan3 Department of Physics & Astronomical Science School of Physical & Material Sciences Central University of Himachal Pradesh (CUHP) Dharamshala, Kangra (HP) INDIA-176215. [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] (Submitted 03-08-2015) Abstract The Keplerian distribution of velocities is not observed in the rotation of large scale structures, such as found in the rotation of spiral galaxies. The deviation from Keplerian distribution provides compelling evidence of the presence of non-luminous matter i.e. called dark matter. There are several astrophysical motivations for investigating the dark matter in and around the galaxy as halo. In this work we address various theoretical and experimental indications pointing towards the existence of this unknown form of matter. Amongst its constituents neutrino is one of the most prospective candidates. We know the neutrinos oscillate and have tiny masses, but there are also signatures for existence of heavy and light sterile neutrinos and possibility of their mixing. Altogether, the role of neutrinos is of great interests in cosmology and understanding dark matter. arXiv:1711.10564v1 [physics.pop-ph] 23 Nov 2017 1 Introduction revealed in 2013 that our Universe contains 68:3% of dark energy, 26:8% of dark matter, and only 4:9% of the Universe is known mat- As a human being the biggest surprise for us ter which includes all the stars, planetary sys- was, that the Universe in which we live in tems, galaxies, and interstellar gas etc.. This is mostly dark. -

A Derivation of Modified Newtonian Dynamics

Journal of The Korean Astronomical Society http://dx.doi.org/10.5303/JKAS.2013.46.2.93 46: 93 ∼ 96, 2013 April ISSN:1225-4614 c 2013 The Korean Astronomical Society. All Rights Reserved. http://jkas.kas.org A DERIVATION OF MODIFIED NEWTONIAN DYNAMICS Sascha Trippe Department of Physics and Astronomy, Seoul National University, Seoul 151-742, Korea E-mail : [email protected] (Received February 14, 2013; Revised March 20, 2013; Accepted March 29, 2013) ABSTRACT Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND) is a possible solution for the missing mass problem in galac- tic dynamics; its predictions are in good agreement with observations in the limit of weak accelerations. However, MOND does not derive from a physical mechanism and does not make predictions on the transitional regime from Newtonian to modified dynamics; rather, empirical transition functions have to be constructed from the boundary conditions and comparisons with observations. I compare the formalism of classical MOND to the scaling law derived from a toy model of gravity based on virtual massive gravitons (the “graviton picture”) which I proposed recently. I conclude that MOND naturally derives from the “graviton picture” at least for the case of non-relativistic, highly symmetric dynamical systems. This suggests that – to first order – the “graviton picture” indeed provides a valid candidate for the physical mechanism behind MOND and gravity on galactic scales in general. Key words : Gravitation — Galaxies: kinematics and dynamics −10 −2 1. INTRODUCTION where x = ac/am, am ≈ 10 ms is Milgrom’s con- stant, and µ(x)isa transition function with the asymp- “ It is worth remembering that all of the discus- totic behavior µ(x) → 1 for x ≫ 1 and µ(x) → x for sion [on dark matter] so far has been based on x ≪ 1. -

The Contents of the Universe

Ay 127! The Contents of the Universe 0.5 % Stars and other visible stuff Supernovae alone ⇒ Accelerating expansion ⇒ Λ > 0 CMB alone ⇒ Flat universe ⇒ Λ > 0 Any two of SN, CMB, LSS ⇒ Dark energy ~70% Also in agreement with the age estimates (globular clusters, nucleocosmochronology, white dwarfs) Today’s Best Guess Universe Age: Best fit CMB model - consistent with ages of oldest stars t0 =13.82 ± 0.05 Gyr Hubble constant: CMB + HST Key Project to -1 -1 measure Cepheid distances H0 = 69 km s Mpc € Density of ordinary matter: CMB + comparison of nucleosynthesis with Lyman-a Ωbaryon = 0.04 € forest deuterium measurement Density of all forms of matter: Cluster dark matter estimate CMB power spectrum 0.31 € Ωmatter = Cosmological constant: Supernova data, CMB evidence Ω = 0.69 for a flat universe plus a low € Λ matter density € The Component Densities at z ~ 0, in critical density units, assuming h ≈ 0.7 Total matter/energy density: Ω0,tot ≈ 1.00 From CMB, and consistent with SNe, LSS From local dynamics and LSS, and Matter density: Ω0,m ≈ 0.31 consistent with SNe, CMB From cosmic nucleosynthesis, Baryon density: Ω0,b ≈ 0.045 and independently from CMB Luminous baryon density: Ω0,lum ≈ 0.005 From the census of luminous matter (stars, gas) Since: Ω0,tot > Ω0,m > Ω0,b > Ω0,lum There is baryonic dark matter There is non-baryonic dark matter There is dark energy The Luminosity Density Integrate galaxy luminosity function (obtained from large redshift surveys) to obtain the mean luminosity density at z ~ 0 8 3 SDSS, r band: ρL = (1.8 ± 0.2) 10 h70 L/Mpc 8 3 2dFGRS, b band: ρL = (1.4 ± 0.2) 10 h70 L/Mpc Luminosity To Mass Typical (M/L) ratios in the B band along the Hubble sequence, within the luminous portions of galaxies, are ~ 4 - 5 M/L This includes some dark matter - for pure stellar populations, (M/L) ratios should be slightly lower. -

Modified Newtonian Dynamics, an Introductory Review

Modified Newtonian Dynamics, an Introductory Review Riccardo Scarpa European Southern Observatory, Chile E-mail [email protected] Abstract. By the time, in 1937, the Swiss astronomer Zwicky measured the velocity dispersion of the Coma cluster of galaxies, astronomers somehow got acquainted with the idea that the universe is filled by some kind of dark matter. After almost a century of investigations, we have learned two things about dark matter, (i) it has to be non-baryonic -- that is, made of something new that interact with normal matter only by gravitation-- and, (ii) that its effects are observed in -8 -2 stellar systems when and only when their internal acceleration of gravity falls below a fix value a0=1.2×10 cm s . Being completely decoupled dark and normal matter can mix in any ratio to form the objects we see in the universe, and indeed observations show the relative content of dark matter to vary dramatically from object to object. This is in open contrast with point (ii). In fact, there is no reason why normal and dark matter should conspire to mix in just the right way for the mass discrepancy to appear always below a fixed acceleration. This systematic, more than anything else, tells us we might be facing a failure of the law of gravity in the weak field limit rather then the effects of dark matter. Thus, in an attempt to avoid the need for dark matter many modifications of the law of gravity have been proposed in the past decades. The most successful – and the only one that survived observational tests -- is the Modified Newtonian Dynamics. -

Cosmology Meets Condensed Matter

Cosmology Meets Condensed Matter Mark N. Brook Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. July 2010 The Feynman Problem-Solving Algorithm: 1. Write down the problem 2. Think very hard 3. Write down the answer – R. P. Feynman att. to M. Gell-Mann Supervisor: Prof. Peter Coles Examiners: Prof. Ed Copeland Prof. Ray Rivers Abstract This thesis is concerned with the interface of cosmology and condensed matter. Although at either end of the scale spectrum, the two disciplines have more in common than one might think. Condensed matter theorists and high-energy field theorists study, usually independently, phenomena embedded in the structure of a quantum field theory. It would appear at first glance that these phenomena are disjoint, and this has often led to the two fields developing their own procedures and strategies, and adopting their own nomenclature. We will look at some concepts that have helped bridge the gap between the two sub- jects, enabling progress in both, before incorporating condensed matter techniques to our own cosmological model. By considering ideas from cosmological high-energy field theory, we then critically examine other models of astrophysical condensed mat- ter phenomena. In Chapter 1, we introduce the current cosmological paradigm, and present a somewhat historical overview of the interplay between cosmology and condensed matter. Many concepts are introduced here that later chapters will follow up on, and we give some examples in which condensed matter physics has had a very real effect on informing cosmology. We also reflect on the most recent incarnations of the condensed matter / cosmology interplay, and the future of these developments. -

Cosmological N-Body Simulations with Generic Hot Dark Matter

Prepared for submission to JCAP Cosmological N-body simulations with generic hot dark matter Jacob Brandbyge,a;b Steen Hannestada aDepartment of Physics and Astronomy, University of Aarhus, Ny Munkegade 120, DK{8000 Aarhus C, Denmark bCentre for Star and Planet Formation, Niels Bohr Institute & Natural History Museum of Denmark, University of Copenhagen, Øster Voldgade 5-7, DK{1350 Copenhagen, Denmark E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. We have calculated the non-linear effects of generic fermionic and bosonic hot dark matter components in cosmological N-body simulations. For sub-eV masses, the non- linear power spectrum suppression caused by thermal free-streaming resembles the one seen for massive neutrinos, whereas for masses larger than 1eV, the non-linear relative suppression of power is smaller than in linear theory. We furthermore find that in the non-linear regime, one can map fermionic to bosonic models by performing a simple transformation. arXiv:1706.00025v1 [astro-ph.CO] 31 May 2017 Contents 1 Introduction1 2 Hot dark matter in linear theory2 2.1 Power spectrum suppression2 2.2 Phase space distribution of the hot dark matter4 2.3 Current constraints from linear theory4 3 Simulation methods6 3.1 Cosmology and initial conditions6 3.2 Different hot dark matter simulation methods7 3.3 The correlation of bulk and thermal velocities7 4 Non-linear results8 4.1 Generic hot dark matter power spectrum suppression 10 4.2 Fermions versus bosons 11 4.3 Convergence 13 5 Discussion and conclusions 13 1 Introduction Although many different types of observations constrain the dominant dark matter compo- nent of the Universe to be cold, a sub-dominant hot dark matter (HDM) component cannot be excluded. -

Dark Matter and Dark Energy: Summary and Future Directions

Dark Matter and Dark Energy: Summary and Future Directions By John Ellis TH Division, CERN, Geneva, Switzerland CERN–TH/2003-086 astro-ph/0304183 April 2003 This paper reviews the progress reported at this Royal Society Discussion Meeting and advertizes some possible future directions in our drive to understand dark matter and dark energy. Additionally, a first attempt is made to place in context the exciting new results from the WMAP satellite, which were published shortly after this Meeting. In the first part of this review, pieces of observational evidence shown here that bear on the amounts of dark matter and dark energy are reviewed. Subsequently, particle candidates for dark matter are mentioned, and detection strategies are discussed. Finally, ideas are presented for calculating the amounts of dark matter and dark energy, and possibly relating them to laboratory data. Keywords: cosmology, particle physics, dark matter, dark energy 1. The Density Budget of the Universe It is convenient to express the mean densities ρi of various quantities in the Universe in terms of their fractions relative to the critical density: Ωi ρi/ρcrit. The theory of cosmological inflation strongly suggests that the the total≡ density should be very close to the critical one: Ωtot 1, and this is supported by the available data on the cosmic microwave background' radiation (CMB) (Bond 2003). The fluctuations 5 observed in the CMB at a level 10− in amplitude exhibit a peak at a partial wave ` 200, as would be produced∼ by acoustic oscillations in a flat Universe with ∼ Ωtot 1. At lower partial waves, ` 200, the CMB fluctuations are believed to be dominated' by the Sachs-Wolfe effect due to the gravitational potential, and more acoustic oscillations are expected at larger `>200, whose relative heights depend on the baryon density Ωb. -

Closing the Window on Warm Dark Matter

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk LAPTH-852/01; astro-ph/0106108brought to you by CORE provided by CERN Document Server Closing the Window on Warm Dark Matter Steen H. Hansen1, Julien Lesgourgues2, Sergio Pastor3, Joseph Silk1 1 Department of Physics, Nuclear & Astrophysics Laboratory, University of Oxford, Keble Road, Oxford OX1 3RH, U.K. 2 Laboratoire de Physique Th´eorique LAPTH, B.P. 110, F-74941 Annecy-le-Vieux Cedex, France 3 Max-Planck-Institut f¨ur Physik (Werner-Heisenberg-Institut), F¨ohringer Ring 6, D-80805, Munich, Germany Sterile neutrinos may be one of the best Warm Dark Matter candidates we have today. Both lower and upper bounds on the mass of the sterile neutrino come from astronomical observations. We show that the proper inclusion of the neutrino momentum distribution and the solution of the kinetic equations with the correct coherence breaking terms lead to the near exclusion of the sterile neutrino as a dark matter candidate. PACS number(s): 14.60.Pq, 14.60.St, 95.35.+d I. INTRODUCTION do massless neutrinos. Therefore they do not share the entropy release from the successive particle annihilations. Astrophysics provides an increasing amount of inde- Since they were relativistic at decoupling, their distribu- pendent indications that the dark matter of the universe tion function in momentum space is subsequently that of is warm, so that the small-scale fluctuations are damped a massless fermion, but with a temperature, TW , which out by free streaming. This is most easily achieved by is given today by giving a keV mass to the DM particle, in which case the 1=3 preferred candidate is the sterile neutrino. -

Baryonic and Non-Baryonic Dark Matter in Massive Galaxies

Baryonic and Non-Baryonic Dark Matter: Halo Contraction and the IMF Matt Auger UC Santa Barbara Tommaso Treu, Raphael Gavazzi, Adam Bolton, Leon Koopmans, Phil Marshall Refrain: Strong Gravitational Lensing Background Source Multiply-Imaged by Massive Foreground Galaxy Image Separation depends on: - lens and source redshifts (geometry) - lensing galaxy mass First Verse: The Sloan Lens ACS (SLACS) Survey SLACS Strong Lens Factory Late-type Background Source Early-type Foreground Lens SLACS Strong Lens Factory [OII] from source Ca K&H from Lens Second Verse: Properties of Early-Type Galaxies ETGs show remarkably tight scaling relations between size, velocity dispersion and ... FP M*P MP Surface Stellar mass Total mass brightness density density Hyper-plane Relations Relationship between: - size - velocity dispersion - total mass in Re/2 - stellar mass Consistent with no intrinsic scatter, no dependence on stellar mass More Massive Galaxies have More Central Dark Matter Total M/L M/L `dark' matter Stellar M/L mass Dark Matter could be CDM or could be baryons not described by the IMF Third Verse: The Important Physical Properties and Mechanisms Three Key Ingredients - Star-formation efficiency (mass dependent) - Dark matter (response to baryons?) - IMF (mass-dependent ??) Star Formation Efficiency Increasing Satellite kinematics efficiency and weak lensing broadly confirm the expected trends of decreased eff. at high and low mass due to feedback from AGN and stars Dutton et al 2010 Abundance Matching Moster et al 2010 Cold Dark Matter Halo NFW Halos from N-body Simulations ETGs are dominated by baryons at small radii Cold Dark Matter Halo Cooling of baryons causes the halo to contract Gnedin et al 2004 Cold Dark Matter Halo Halo contraction may depend on the amount of baryons and how the baryons got there Dynamical friction can `puff up' halos.. -

Baryonic and Non-Baryonic Dark Matter

Baryonic and Non-Baryonic Dark Mat- ter Bernard CARR Astronomy Unit, Queen Mary & Westfield College, Mile End Road, London E1 4NS, England, [email protected] Abstract Cosmological nucleosynthesis calculations imply that there should be both non-baryonic and baryonic dark matter. Recent data suggest that some of the non-baryonic dark matter must be “hot” (i.e. massive neutrinos) and there may also be evidence for “cold” dark matter (i.e. WIMPs). If the baryonic dark matter resides in galactic halos, it is likely to be in the form of compact objects (i.e. MACHOs) and these would probably be the remnants of a first generation of pregalactic or protogalactic Population III stars. Many candidates have been proposed - brown dwarfs, red dwarfs, white dwarfs or black holes - and at various times each of these has been in vogue. We review the many types of observations which can be used to constrain or exclude both baryonic and non-baryonic dark matter candidates. 1. Introduction arXiv:gr-qc/0008005v1 1 Aug 2000 Evidence for dark matter has been claimed in many different contexts. There may be local dark matter in the Galactic disc, dark matter in the halos of our own and other galaxies, dark matter associated with clusters of galaxies and finally - if one believes that the total cosmological density has the critical value - smoothly distributed background dark matter. Since dark matter probably takes as many different forms as visible matter, it would be simplistic to assume that all these dark matter problems have a single solution. The local dark matter is almost certainly unrelated to the other ones and, while the halo and cluster dark matter would be naturally connected in many evolutionary scenarios, there is a growing tendency to regard the unclustered background dark matter as different from the clustered component.