Not to Be Printed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Royal Air Force Historical Society Journal 29

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 29 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Copyright 2003: Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 2003 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361-4231 Typeset by Creative Associates 115 Magdalen Road Oxford OX4 1RS Printed by Advance Book Printing Unit 9 Northmoor Park Church Road Northmoor OX29 5UH 3 CONTENTS BATTLE OF BRITAIN DAY. Address by Dr Alfred Price at the 5 AGM held on 12th June 2002 WHAT WAS THE IMPACT OF THE LUFTWAFFE’S ‘TIP 24 AND RUN’ BOMBING ATTACKS, MARCH 1942-JUNE 1943? A winning British Two Air Forces Award paper by Sqn Ldr Chris Goss SUMMARY OF THE MINUTES OF THE SIXTEENTH 52 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING HELD IN THE ROYAL AIR FORCE CLUB ON 12th JUNE 2002 ON THE GROUND BUT ON THE AIR by Charles Mitchell 55 ST-OMER APPEAL UPDATE by Air Cdre Peter Dye 59 LIFE IN THE SHADOWS by Sqn Ldr Stanley Booker 62 THE MUNICIPAL LIAISON SCHEME by Wg Cdr C G Jefford 76 BOOK REVIEWS. 80 4 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air Marshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-Marshal -

Premier Apartments #Beaufortpark

#BeaufortPark #BeaufortPark London living made easy Beaufort Park is a thriving Beaufort Park is exceptionally well located for work and 02 destination in North play. King’s Cross, home to tech giants Google, YouTube 03 and Facebook, is just a short journey away. West London, one with a rich history in aviation, There are also a variety of cultural and leisure attractions on the doorstep. Brent Cross, the retail and leisure and provides homes set complex, is within easy reach and will soon be London’s amongst a variety of shops largest shopping centre. and restaurants, with Close by is Hampstead Village with its boutiques, cobbled excellent facilities including streets and views of London from Hampstead Heath. a residents-only spa, gym Beaufort Park is perfectly located to an outstanding and swimming pool. selection of schools and nearby Middlesex University. The nearby London Underground Station provides swift and convenient access to Central London with 24-hour weekend service. This is London living at its very best. YOU’VE ARRIVED Premier Apartments #BeaufortPark 04 Distinctive design 05 Beaufort Park is an inspiring place to be. These stylish premier three bedroom homes offer spacious, light-filled living spaces with contemporary interiors. Quality specification homes are accompanied by stunning views over North West London, landscaped parkland or courtyard. The exclusive, residents-only spa is home to a large fitness studio, fully-equipped gym, indoor swimming pool, sauna and jacuzzi. The Castleton and Celeste Apartments, named in continuation of the aviation history of the development, provides exclusive city living. YOU’VE ARRIVED Premier Apartments #BeaufortPark Bentfield Hucks’s first loop-the-loop was celebrated with an upside-down dinner, with tables arranged in a loop, and a menu that started with dessert and finished with the starter. -

The EVOLUTION of an AIRPORT

GATWICK The EVOLUTION of an AIRPORT JOHN KING Gatwick Airport Limited and Sussex Industrial Archaeology Society _SUSSEX_ INDUSTRIAL HISTORY journal of the Sussex Industrial Archaeology Society GATWICK The EVOLUTION of an AIRPORT john King Issue No. 16 Produced in conjunction with Gatwick Airport Ltd. 1986 ISSN 0263 — 5151 CONTENTS 1 . The Evolution of an Airport 1 2 . The Design Problem 12 3. Airports Ltd .: Private to Public 16 4 . The First British Airways 22 5. The Big Opening 32 6. Operating Difficulties 42 7. Merger Problems 46 8. A Sticky Patch 51 9. The Tide Turns 56 10. The Military Arrive 58 11 . The Airlines Return 62 12. The Visions Realised 65 Appendix 67 FOREWORD Air Marshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC This is a story of determination and endeavour in the face of many difficulties — the site, finance and "the authorities" — which had to be overcome in the significant achievement of the world's first circular airport terminal building . A concept which seems commonplace now was very revolutionary fifty years ago, and it was the foresight of those who achieved so much which springs from the pages of John King's fascinating narrative. Although a building is the central character, the story rightly involves people because it was they who had to agonise over the decisions which were necessary to achieve anything. They had the vision, but they had to convince others : they had to raise the cash, to generate the publicity, to supervise the work — often in the face of opposition to Gatwick as a commercial airfield. -

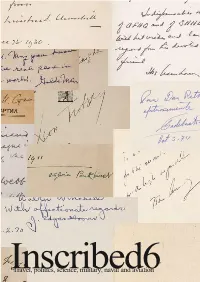

Inscribed 6 (2).Pdf

Inscribed6 CONTENTS 1 1. AVIATION 33 2. MILITARY 59 3. NAVAL 67 4. ROYALTY, POLITICIANS, AND OTHER PUBLIC FIGURES 180 5. SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 195 6. HIGH LATITUDES, INCLUDING THE POLES 206 7. MOUNTAINEERING 211 8. SPACE EXPLORATION 214 9. GENERAL TRAVEL SECTION 1. AVIATION including books from the libraries of Douglas Bader and “Laddie” Lucas. 1. [AITKEN (Group Captain Sir Max)]. LARIOS (Captain José, Duke of Lerma). Combat over Spain. Memoirs of a Nationalist Fighter Pilot 1936–1939. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. 8vo., cloth, pictorial dust jacket. London, Neville Spearman. nd (1966). £80 A presentation copy, inscribed on the half title page ‘To Group Captain Sir Max AitkenDFC. DSO. Let us pray that the high ideals we fought for, with such fervent enthusiasm and sacrifice, may never be allowed to perish or be forgotten. With my warmest regards. Pepito Lerma. May 1968’. From the dust jacket: ‘“Combat over Spain” is one of the few first-hand accounts of the Spanish Civil War, and is the only one published in England to be written from the Nationalist point of view’. Lerma was a bomber and fighter pilot for the duration of the war, flying 278 missions. Aitken, the son of Lord Beaverbrook, joined the RAFVR in 1935, and flew Blenheims and Hurricanes, shooting down 14 enemy aircraft. Dust jacket just creased at the head and tail of the spine. A formidable Vic formation – Bader, Deere, Malan. 2. [BADER (Group Captain Douglas)]. DEERE (Group Captain Alan C.) DOWDING Air Chief Marshal, Lord), foreword. Nine Lives. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. -

FOR ENGLAND August 2018

St GEORGE FOR ENGLAND DecemberAugust 20182017 In this edition The Murder of the Tsar The Royal Wedding Cenotaph Cadets Parade at Westminster Abbey The Importance of Archives THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF St. GEORGE – The Premier Patriotic Society of England Founded in 1894. Incorporated by Royal Charter. Patron: Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II £3.50 Proud to be working with The Royal Society of St. George as the of cial printer of "St. George for England". One of the largest printing groups in the UK with six production sites. We offer the following to an extensive portfolio of clients and market sectors: • Our services: Printing, Finishing, Collation, Ful lment, Pick & Pack, Mailing. • Our products: Magazines, Brochures, Lea ets, Catalogues and Training Manuals. • Our commitment: ISO 14001, 18001, 9001, FSC & PEFC Accreditation. wyndehamgroup Call Trevor Stevens on 07917 576478 $$%# #%)( $#$#!#$%( '#$%) # &%#% &#$!&%)%#% % !# %!#$#'%&$&#$% % #)# ( #% $&#%%%$% ##)# %&$% '% &%&# #% $($% %# &%% ) &! ! #$ $ %# & &%% &# &#)%'%$& #$(%%(#)&#$'!#%&# %%% % #)# &%#!# %$ # #$#) &$ $ #'%% !$$ %# & &# ## $#'$(# # &"&%)*$ &#$ # %%!#$% &$ ## (#$ #) &! ! '#)##'$'*$)#!&$'%% $% '#%) % '%$& &#$% #(##$##$$)"&%)$!#$# # %#%$ # $% # # #% !$ %% #'$% # +0 +))%)$ -0$,)'*(0&$'$- 0".+(- + "$,- + $(("&()'*(0) ( "$,- + #+$-0) "$,- + !!$ (+ ,,!)+)++ ,*)( ( # -.$))*0#)&+'0+)/ )+$(" -# $(" Contents Vol 16. No. 2 – August 2018 Front Cover: Tower Bridge, London 40 The Royal Wedding 42 Cenotaph Cadets Parade and Service at Westminster St George -

A Glider Pilot Bold... Wally Kahn a Glider Pilot Bold

A Glider Pilot Bold.. f ttom % fRfltng liBttattg of A Glider Pilot Bold... Wally Kahn A Glider Pilot Bold... Wally Kahn First edition published by Jardine Publishers 1998 Second edition published by Airplan Flight Equipment Ltd Copyright ©2008 Third edition published by Walter Kahn 2011 Copyright ©WALTER KAHN (1998 & 2008) and Airplan Flight Equipment (2008) WALTER KAHN 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a newspaper, magazine, or radio or television broadcast. Every effort has been made by the author and the publishers to trace owners of copyright material. The events described have been cross-checked wherever possible and the author apologises for any errors or omissions which may have arisen. Cover photograph courtesy Neil Lawson. White Planes Co A Glider Pilot Bold... 1st Edition original cover Contents Another bite of the cherry .................................................................................9 Chapter 1 The early days and Oerlinghausen ..........................................15 Chapter 2 More Oerlinghausen.................................................................19 Chapter 3 Mindeheide and Scharfholdendorf ...........................................29 Chapter 4 Dunstable and Redhill -

British Rainfall 1950

RELATION OF RAINFALL IN 1950 TO THE AVERAGE OF 1881-1915. RAINFALL IN SCALE OF TINTS 1950 PERCENT OF AVERAGE 0 50 100 AIR MINISTRY, METEOROLOGICAL OFFICE. The area coloured Red had rainfall below the average, that coloured Blue had rainfall above the average. British Rainfall, 1950 } [ Frontispiece 4756-4402-M.3171-750-IO/5Z.(M.F P.) M.O. 560 AIR MINISTRY METEOROLOGICAL OFFICE BRITISH RAINFALL 1950 THE NINETIETH ANNUAL VOLUME OF THE BRITISH RAINFALL ORGANIZATION Report on the DISTRIBUTION OF RAIN IN SPACE AND TIME OVER GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND DURING THE YEAR 1950 AS RECORDED BY ABOUT 5,000 OBSERVERS WITH MAPS 60549 LONDON : HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE 1952 CROWN COPYRIGHT RESERVED PUBLISHED BY HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE To be purchased from York House, Kingsway, LONDON, w.c.2 423 Oxford Street, LONDON, w.l P.O. Box 569, LONDON, s.E.l 13a Castle Street, EDINBURGH, 2 1 St. Andrew's Crescent, CARDIFF 39 King Street, MANCHESTER, 2 Tower Lane, BRISTOL, 1 2 Edmund Street, BIRMINGHAM, 3 80 Chichester Street, BELFAST or from any Bookseller 1952 Price £1 5s. Off. net S.O, Code No. 40 10-0-50* CONTENTS PAGE PAGE PART I PART ffl 1. THE WORK OF THE BRITISH RAINFALL PAPERS ON RAINFALL IN British Rainfall ORGANIZATION British Rainfall 1926-1950 .. .. .. ..208 1950 Local Organizations — The AVERAGE MONTHLY AND ANNUAL RAIN Staff of Observers — Investigations FALL OVER EACH COUNTY OF ENGLAND —Inspections—Inquiries—Obituary 1 AND WALES .. .. .. .. 215 2. THE DISTRIBUTION OF RAINFALL IN TIME DAYS WITH RAIN 5 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS 3. -

Second World War Roll of Honour

Second World War roll of honour This document lists the names of former Scouts and Scout Leaders who were killed during the Second World War (1939 – 1945). The names have been compiled from official information gathered at and shortly after the War and from information supplied by several Scout historians. We welcome any names which have not been included and, once verified through the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, will add them to the Roll. We are currently working to cross reference this list with other sources to increase its accuracy. Name Date of Death Other Information RAF. Aged 21 years. Killed on active service, 4th February 1941. 10th Barking Sergeant Bernard T. Abbott 4 February 1941 (Congregational) Group. Army. Aged 21 years. Killed on active service in France, 21 May 1940. 24th Corporal Alan William Ablett 21 May 1940 Gravesend (Meopham) Group. RAF. Aged 22 years. Killed on active service, February 1943. 67th North Sergeant Pilot Gerald Abrey February 1943 London Group. South African Air Force. Aged 23 years. Killed on active service in air crash Jan Leendert Achterberg 14 May 1942 14th May, 1942. 1st Bellevue Group, Johannesburg, Transvaal. Flying Officer William Ward RAF. Aged 25 years. Killed on active service 15 March 1940. Munroe College 15 March 1940 Adam Troop, Ontonio, Jamaica. RAF. Aged 23 years. Died on active service 4th June 1940. 71st Croydon Denis Norman Adams 4 June 1940 Group. Pilot Officer George Redvers RAF. Aged 23 years. Presumed killed in action over Hamburg 10th May 1941. 10 May 1940 Newton Adams 8th Ealing Group. New Zealand Expeditionary Force. -

Material Cultures of Childhood in Second World War Britain

Material Cultures of Childhood in Second World War Britain How do children cope when their world is transformed by war? This book draws on memory narratives to construct an historical anthropology of childhood in Second World Britain, focusing on objects and spaces such as gas masks, air raid shelters and bombed-out buildings. In their struggles to cope with the fears and upheavals of wartime, with families divided and familiar landscapes lost or transformed, children reimagined and reshaped these material traces of conflict into toys, treasures and playgrounds. This study of the material worlds of wartime childhood offers a unique viewpoint into an extraordinary period in history with powerful resonances across global conflicts into the present day. Gabriel Moshenska is Associate Professor in Public Archaeology at University College London, UK. Material Culture and Modern Conflict Series editors: Nicholas J. Saunders, University of Bristol, Paul Cornish, Imperial War Museum, London Modern warfare is a unique cultural phenomenon. While many conflicts in history have produced dramatic shifts in human behaviour, the industrialized nature of modern war possesses a material and psychological intensity that embodies the extremes of our behaviours, from the total economic mobiliza- tion of a nation state to the unbearable pain of individual loss. Fundamen- tally, war is the transformation of matter through the agency of destruction, and the character of modern technological warfare is such that it simulta- neously creates and destroys more than any previous kind of conflict. The material culture of modern wars can be small (a bullet, machine-gun or gas mask), intermediate (a tank, aeroplane, or war memorial), and large (a battleship, a museum, or an entire contested landscape). -

Aeromodeller December 1960

SILVER C f j r is t n m s isisiiic DECEMBER I960 ρε-m e z a p / o co/rrzoi ε/rs 44 The most comprehensive prefabrication ever undertaken in a kit of this siz e .......... ’» R M A “V I K I N G ” 60 span. For 2.5 to 5 c.c. Diesel or Glo Motors. A European Championship design by Swedish ace Erik Berglund. Suitable for all types of Radio installations. Super Pre-Fab Kit contains every thing including Airwhccls. Cut wing ribs. Ready-made U/C, finished fuselage sides, formers, bulkheads, shaped L.E., T.E., N ose and Tail blocks, etc. etc. down to the last nut and bolt! £6 12/6 ASK TO SEE THEM AT YOUR LOCAL MODEL SHOP TO-DAY! 44 The finest example of die-cutting we have seen Aeromodeller, April, I960 /Λ R M A “ V A G A B O N D ” 59 span. For 2.5 to 5 c.c. motors Superb for sport or contest flying — / simple to build and fly. This super I de luxe kit is absolutely COMPLETE ^ including three airwheels, transfers and all parts shaped, etc.— unrivalled in value and performance. £6/5/0 SVENE TRUDSON SWEDEN MAIN DISTRIBUTORS OF THE COMPLETE RANGE OF E.D. RADIO CONTROL EQUIPMENT BLACK ARROW 4, 6 or 8 CHANNEL RECEIVERS The receiver is completely revolution- ized with a new and absolutely reliable relay and a super sensitive reed unit, capable of operating with an input of o ily 2 volts R.M.S. Using the new high gain Mullard Transistors. -

Records of the British Aviation Industry in the Raf Museum: a Brief Guide

RECORDS OF THE BRITISH AVIATION INDUSTRY IN THE RAF MUSEUM: A BRIEF GUIDE Contents Introduction 2 Section 1: Background to the collection 2 Arrangement of this Guide 3 Access to the records 3 Glossary of terms 4 The British aircraft industry: an overview 3 Section 2: Company histories and description of records 6 Appendix The British Aircraft Industry: a bibliography 42 1 Introduction The RAF Museum holds what is probably Britain's most comprehensive collection of records relating to companies involved in the manufacture of airframes (i.e. aircraft less their engines) aero-engines, components and associated equipment. The entries in this guide are arranged by company name and include a history of each company, particularly its formation and that of subsidiaries together with mergers and take-overs. Brief details of the records, the relevant accession numbers and any limitations on access are given. Where the records have been listed this is indicated. A glossary of terms specific to the subject area is also included, together with an index. Background to the Collection The Museum's archive department began collecting records in the late 1960s and targeted a number of firms. Although many of the deposits were arranged through formal approaches by the Museum to companies, a significant number were offered by company staff: a significant example is the Supermarine archive (AC 70/4) including some 50,000 drawings, which would have been burnt had an employee not contacted the Museum. The collections seem to offer a bias towards certain types of record, notably drawings and production records, rather than financial records and board minutes. -

The Meaning of Hendon: the Royal Air Force Display, Aerial Theatre And

[This is the pre-peer reviewed version of the following article: ‘The meaning of Hendon: the Royal Air Force Display, aerial theatre and the technological sublime, 1920–37’, which has been accepted for publication in Historical Research] The meaning of Hendon: the Royal Air Force Display, aerial theatre and the technological sublime, 1920–37 Brett Holman University of Canberra; University of New England [email protected] https://airminded.org Acknowledgements For their advice and assistance, the author would like to thank the following: Peter Hobbins, Thomas Kehoe, James Kightly, Ross Mahoney, Cathy Schapper and Dorthe Gert Simonsen. Part of this research was supported by University of New England Research Seed Grant 19261. Introduction It is 2 July 1927. Two squadrons of hostile bombers approach London, preparing to unload their deadly cargo on the great metropolis. Fortunately, they are intercepted by two British fighter squadrons, which manage to destroy or turn back the enemy aircraft, albeit at terrible cost to themselves. Shortly afterwards, in a far-flung corner of empire, the European residents of a small village come under attack from their indigenous neighbours. Their distress signals are seen by a British aerial patrol, which radios for assistance. As the colonists withdraw under fire across a bridge, a friendly bomber squadron arrives and targets the hostile insurgents. Three large transport aircraft land nearby and take the white refugees to safety, as the village burns furiously. These battles never happened. Or, rather, they only happened as entertainment, as the spectacular climax to a highly-choreographed and heavily-publicised performance of British airpower: the Royal Air Force (RAF) 1 Display, held annually at Hendon aerodrome in north London between 1920 and 1937, to shape the public image of Britain’s newest arm of defence.1 One day every summer (weather permitting) dozens of military aircraft soared and dived over Hendon, looped and tumbled, flew in formation and fought in mock battles, before huge, enraptured crowds.