Jacques Audiard – Twenty-First Century Auteur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Film Watcher's Guide to Multicultural Films

(Year) The year stated follows the TPL catalogue, based on when the film was released in DVD format. DRAMA CONTINUED Young and Beautiful (2014) [French] La Donation (The Legacy) (2010) [French] Yureru (Sway) (2006) [Japanese] Eccentricities of a Blonde-Haired Girl (2010) FAMILY [Portuguese] Amazonia (2014) [no dialogue] Ekstra (2014) [Tagalog] Antboy (2014) [English] Everyday (2014) [English] A Film Watcher’s The Book of Life (2014) [English/Spanish/French] Force Majeure (2014) [Swedish/English/French] Jack and the Cuckoo-Clock Heart (2013) Gerontophilia (2014) [French/English] Guide To Gett: The Trial of Viviane Amsalem (2015) [English/French] Khumba (2013) [English] [French/Hebrew/Arabic] Song of the Sea (2015) [English/French] Girlhood (2015) [French] Happy-Go-Lucky (2009) [English] HORROR The hundred year-old man who climbed out of a (*includes graphic scenes/violence) window and disappeared (2015) [Swedish/English] Berberian Sound Studio (2012) [English] The Hunt (2013) [Danish] *Borgman (2013) [Dutch/English] I am Yours (2013) [Norwegian/Urdu/Swedish] *Kill List (2011) [English] Ida (2014) [Polish] The Loved Ones (2012) [English] In a Better World (2011) [Danish/French] The Wild Hunt (2010) [English/French] The Last Sentence (2012) [Swedish] Les Neiges du Kilimanjaro (The Snows of ROMANCE Kilimanjaro) (2012) [French] All about Love (2006) [Cantonese/Mandarin] Leviathan (2015) [Russian/English/French] Amour (2013) [French] Like Father, Like Son (2014) [Japanese] Cairo Time (2010) [English/French] Goodbye First Love (2011) [French] -

Film & Event Calendar

1 SAT 17 MON 21 FRI 25 TUE 29 SAT Events & Programs Film & Event Calendar 12:00 Event 4:00 Film 1:30 Film 11:00 Event 10:20 Family Gallery Sessions Tours for Fours: Art-Making Warm Up. MoMA PS1 Sympathy for The Keys of the #ArtSpeaks. Tours for Fours. Daily, 11:30 a.m. & 1:30 p.m. Materials the Devil. T1 Kingdom. T2 Museum galleries Education & 4:00 Film Museum galleries Saturdays & Sundays, Sep 15–30, Research Building See How They Fall. 7:00 Film 7:00 Film 4:30 Film 10:20–11:15 a.m. Join us for conversations and T2 An Evening with Dragonfly Eyes. T2 Dragonfly Eyes. T2 10:20 Family Education & Research Building activities that offer insightful and Yvonne Rainer. T2 A Closer Look for 7:00 Film 7:30 Film 7:00 Film unusual ways to engage with art. Look, listen, and share ideas TUE FRI MON SAT Kids. Education & A Self-Made Hero. 7:00 Film The Wind Will Carry Pig. T2 while you explore art through Research Building Limited to 25 participants T2 4 7 10 15 A Moment of Us. T1 movement, drawing, and more. 7:00 Film 1:30 Film 4:00 Film 10:20 Family Innocence. T1 4:00 Film WED Art Lab: Nature For kids age four and adult companions. SUN Dheepan. T2 Brigham Young. T2 This Can’t Happen Tours for Fours. SAT The Pear Tree. T2 Free tickets are distributed on a 26 Daily. Education & Research first-come, first-served basis at Here/High Tension. -

71 Ans De Festival De Cannes Karine VIGNERON

71 ans de Festival de Cannes Titre Auteur Editeur Année Localisation Cote Les Années Cannes Jean Marie Gustave Le Hatier 1987 CTLes (Exclu W 5828 Clézio du prêt) Festival de Cannes : stars et reporters Jean-François Téaldi Ed du ricochet 1995 CTLes (Prêt) W 4-9591 Aux marches du palais : Le Festival de Cannes sous le regard des Ministère de la culture et La 2001 Salle Santeuil 791 (44) Mar sciences sociales de la communication Documentation française Cannes memories 1939-2002 : la grande histoire du Festival : Montreuil Média 2002 Salle Santeuil 791 (44) Can l’album officiel du 55ème anniversaire business & (Exclu du prêt) partners Le festival de Cannes sur la scène internationale Loredana Latil Nouveau monde 2005 Salle Santeuil 791 (44) LAT Cannes Yves Alion L’Harmattan 2007 Magasin W 4-27856 (Exclu du prêt) En haut des marches, le cinéma : vitrine, marché ou dernier refuge Isabelle Danel Scrineo 2007 Salle Santeuil 791 (44) DAN du glamour, à 60 ans le Festival de Cannes brille avec le cinéma Cannes Auguste Traverso Cahiers du 2007 Salle Santeuil 791 (44) Can cinéma (Exclu du prêt) Hollywood in Cannes : The history of a love-hate relationship Christian Jungen Amsterdam 2014 Magasin W 32950 University press Sélection officielle Thierry Frémaux Grasset 2017 Magasin W 32430 Ces années-là : 70 chroniques pour 70 éditions du Festival de Stock 2017 Magasin W 32441 Cannes La Quinzaine des réalisateurs à Cannes : cinéma en liberté (1969- Ed de la 1993 Magasin W 4-8679 1993) Martinière (Exclu du prêt) Cannes, cris et chuchotements Michel Pascal -

Phoenix Films 1999-2019/20 Sorted by Film Title 10

Phoenix Films 1999-2019/20 Sorted by Film Title Film Date Rating(%) 2046 1-Feb-2006 68 120BPM (Beats Per Minute) 24-Oct-2018 75 3 Coeurs 14-Jun-2017 64 35 Shots of Rum 13-Jan-2010 65 45 Years 20-Apr-2016 83 5 x 2 3-May-2006 65 A Bout de Souffle 23-May-2001 60 A Clockwork Orange 8-Nov-2000 81 A Fantastic Woman 3-Oct-2018 84 A Farewell to Arms 19-Nov-2014 70 A Highjacking 22-Jan-2014 92 A Late Quartet 15-Jan-2014 86 A Man Called Ove 8-Nov-2017 90 A Matter of Life and Death 7-Mar-2001 80 A One and A Two 23-Oct-2001 79 A Prairie Home Companion 19-Dec-2007 79 A Private War 15-May-2019 94 A Room and a Half 30-Mar-2011 75 A Royal Affair 3-Oct-2012 92 A Separation 21-Mar-2012 85 A Simple Life 8-May-2013 86 A Single Man 6-Oct-2010 79 A United Kingdom 22-Nov-2017 90 A Very Long Engagement 8-Jun-2005 80 A War 15-Feb-2017 91 A White Ribbon 21-Apr-2010 75 Abouna 3-Dec-2003 75 About Elly 26-Mar-2014 78 Accident 22-May-2002 72 After Love 14-Feb-2018 76 After the Storm 25-Oct-2017 77 After the Wedding 31-Oct-2007 86 Alice et Martin 10-May-2000 All About My Mother 11-Oct-2000 84 All the Wild Horses 22-May-2019 88 Almanya: Welcome To Germany 19-Oct-2016 88 Amal 14-Apr-2010 91 American Beauty 18-Oct-2000 83 American Honey 17-May-2017 67 American Splendor 9-Mar-2005 78 Amores Perros 7-Nov-2001 85 Amour 1-May-2013 85 Amy 8-Feb-2017 90 An Autumn Afternoon 2-Mar-2016 66 An Education 5-May-2010 86 Anna Karenina 17-Apr-2013 82 Another Year 2-Mar-2011 86 Apocalypse Now Redux 30-Jan-2002 77 Apollo 11 20-Nov-2019 95 Apostasy 6-Mar-2019 82 Aquarius 31-Jan-2018 73 -

12 Big Names from World Cinema in Conversation with Marrakech Audiences

The 18th edition of the Marrakech International Film Festival runs from 29 November to 7 December 2019 12 BIG NAMES FROM WORLD CINEMA IN CONVERSATION WITH MARRAKECH AUDIENCES Rabat, 14 November 2019. The “Conversation with” section is one of the highlights of the Marrakech International Film Festival and returns during the 18th edition for some fascinating exchanges with some of those who create the magic of cinema around the world. As its name suggests, “Conversation with” is a forum for free-flowing discussion with some of the great names in international filmmaking. These sessions are free and open to all: industry professionals, journalists, and the general public. During last year’s festival, the launch of this new section was a huge hit with Moroccan and internatiojnal film lovers. More than 3,000 people attended seven conversations with some legendary names of the big screen, offering some intense moments with artists, who generously shared their vision and their cinematic techniques and delivered some dazzling demonstrations and fascinating anecdotes to an audience of cinephiles. After the success of the previous edition, the Festival is recreating the experience and expanding from seven to 11 conversations at this year’s event. Once again, some of the biggest names in international filmmaking have confirmed their participation at this major FIFM event. They include US director, actor, producer, and all-around legend Robert Redford, along with Academy Award-winning French actor Marion Cotillard. Multi-award-winning Palestinian director Elia Suleiman will also be in attendance, along with independent British producer Jeremy Thomas (The Last Emperor, Only Lovers Left Alive) and celebrated US actor Harvey Keitel, star of some of the biggest hits in cinema history including Thelma and Louise, The Piano, and Pulp Fiction. -

The State, Democracy and Social Movements

The Dynamics of Conflict and Peace in Contemporary South Asia This book engages with the concept, true value, and function of democracy in South Asia against the background of real social conditions for the promotion of peaceful development in the region. In the book, the issue of peaceful social development is defined as the con- ditions under which the maintenance of social order and social development is achieved – not by violent compulsion but through the negotiation of intentions or interests among members of society. The book assesses the issue of peaceful social development and demonstrates that the maintenance of such conditions for long periods is a necessary requirement for the political, economic, and cultural development of a society and state. Chapters argue that, through the post-colo- nial historical trajectory of South Asia, it has become commonly understood that democracy is the better, if not the best, political system and value for that purpose. Additionally, the book claims that, while democratization and the deepening of democracy have been broadly discussed in the region, the peace that democracy is supposed to promote has been in serious danger, especially in the 21st century. A timely survey and re-evaluation of democracy and peaceful development in South Asia, this book will be of interest to academics in the field of South Asian Studies, Peace and Conflict Studies and Asian Politics and Security. Minoru Mio is a professor and the director of the Department of Globalization and Humanities at the National Museum of Ethnology, Japan. He is one of the series editors of the Routledge New Horizons in South Asian Studies and has co-edited Cities in South Asia (with Crispin Bates, 2015), Human and International Security in India (with Crispin Bates and Akio Tanabe, 2015) and Rethinking Social Exclusion in India (with Abhijit Dasgupta, 2017), also pub- lished by Routledge. -

The Reel World: Contemporary Issues on Screen

The Reel World: Contemporary Issues on Screen Films • “Before the Rain” (Macedonia 1994) or “L’America” (Italy/Albania 1994) • “Earth” (India 1998) • “Xiu-Xiu the Sent Down Girl” (China 1999) • (OPTIONAL): “Indochine” (France/Vietnam 1992) • “Zinat” (Iran 1994) • “Paradise Now” (Palestine 2005) • “Hotel Rwanda” (Rwanda 2004) • (OPTIONAL): “Lumumba” (Zaire 2002) • “A Dry White Season” (South Africa 1989) • “Missing” (US/Chile 1982) • “Official Story” (Argentina 1985) • “Men With Guns” (Central America 1997) Books • We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will be Killed With Our Families: Stories from Rwanda by Philip Gourevitch • (OPTIONAL/RECOMMENDED): A Dry White Season by André Brink Course Goals There are several specific goals to achieve for the course: Students will learn to view films historically as one of a number of sources offering an interpretation of the past Students will acquire a knowledge of the key terms, facts, and events in contemporary world history and thereby gain an informed historical perspective Students will take from the class the skills to critically appraise varying historical arguments based on film and to clearly express their own interpretations Students will develop the ability to synthesize and integrate information and ideas as well as to distinguish between fact and opinion Students will be encouraged to develop an openness to new ideas and, most importantly, the capacity to think critically Course Activities and Procedures This course is taught in conjunction with “The Contemporary World,” although that course is not a prerequisite. We will use material from that course as background and context for the films we see. Students who have already taken “The Contemporary World” can review the material to refresh their memories before watching the relevant titles if they feel the need to do so. -

Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND Index 2016_4.indd 1 14/12/2016 17:41 SUBJECT INDEX SUBJECT INDEX After the Storm (2016) 7:25 (magazine) 9:102 7:43; 10:47; 11:41 Orlando 6:112 effect on technological Film review titles are also Agace, Mel 1:15 American Film Institute (AFI) 3:53 Apologies 2:54 Ran 4:7; 6:94-5; 9:111 changes 8:38-43 included and are indicated by age and cinema American Friend, The 8:12 Appropriate Behaviour 1:55 Jacques Rivette 3:38, 39; 4:5, failure to cater for and represent (r) after the reference; growth in older viewers and American Gangster 11:31, 32 Aquarius (2016) 6:7; 7:18, Céline and Julie Go Boating diversity of in 2015 1:55 (b) after reference indicates their preferences 1:16 American Gigolo 4:104 20, 23; 10:13 1:103; 4:8, 56, 57; 5:52, missing older viewers, growth of and A a book review Agostini, Philippe 11:49 American Graffiti 7:53; 11:39 Arabian Nights triptych (2015) films of 1970s 3:94-5, Paris their preferences 1:16 Aguilar, Claire 2:16; 7:7 American Honey 6:7; 7:5, 18; 1:46, 49, 53, 54, 57; 3:5: nous appartient 4:56-7 viewing films in isolation, A Aguirre, Wrath of God 3:9 10:13, 23; 11:66(r) 5:70(r), 71(r); 6:58(r) Eric Rohmer 3:38, 39, 40, pleasure of 4:12; 6:111 Aaaaaaaah! 1:49, 53, 111 Agutter, Jenny 3:7 background -

Press Information September | October 2016 Choice of Arms The

Press Information September | October 2016 Half a century of modern French crime thrillers and Samuel Beckett and Buster Keaton 's collaboration of the century in the year of 1965; the politically aware work of documentary filmmaker Helga Reidemeister and the seemingly apolitical "hipster" cinema of the Munich Group between 1965 and 1970: these four topics will launch the 2016/17 season at the Austrian Film Museum. Furthermore, the Film Museum will once again take part in the Long Night of the Museums (October 1); a new semester of our education program School at the Cinema begins on October 13, and the upcoming publications ( Alain Bergala's book The Cinema Hypothesis and the DVD edition of Josef von Sternberg's The Salvation Hunters ) are nearing completion. Latest Film Museum restorations are presented at significant film festivals – most recently, Karpo Godina's wonderful "film-poems" (1970-72) were shown at the Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna – the result of a joint restoration project conducted with Slovenska kinoteka. As the past, present and future of cinema have always been intertwined in our work, we are particularly glad to announce that Michael Palm's new film Cinema Futures will have its world premiere at the Venice Film Festival on September 2 – the last of the 21 projects the Film Museum initiated on the occasion of its 50th anniversary in 2014. Choice of Arms The French Crime Thriller 1958–2009 To start off the season, the Film Museum presents Part 2 of its retrospective dedicated to French crime cinema. Around 1960, propelled by the growth spurt of the New Wave, the crime film was catapulted from its "classical" period into modernity. -

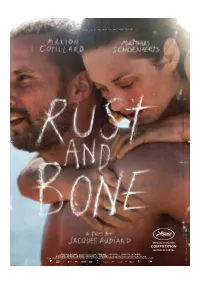

Marion Cotillard Matthias Schoenaerts RUST AND

RustnBone1.indd 1 6/5/12 15:12:51 Why Not Productions and Page 114 present Marion Cotillard Matthias Schoenaerts RUST AND BONE A film by Jacques Audiard Armand Verdure / Céline Sallette / Corinne Masiero Bouli Lanners / Jean-Michel Correia France / Belgium / 2012 / color / 2.40 / 120 min International Press: International Sales: Magali Montet Celluloid Dreams [email protected] 2, rue Turgot - 75009 Paris Tel: +33 6 71 63 36 16 Tel: +33 1 4970 0370 Fax: +33 1 4970 0371 Delphine Mayele [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +33 6 60 89 85 41 Contact in Cannes Celluloid Dreams 84, rue d’Antibes 06400 Cannes Hengameh Panahi +33 6 11 96 57 20 Annick Mahnert +33 6 37 12 81 36 Agathe Mauruc +33 6 82 73 80 04 Director’s Note There is something gripping about Craig Davidson’s short story collection “Rust and Bone”, a depiction of a dodgy, modern world in which individual lives and simple destinies are blown out of all proportion by drama and accident. They offer a vision of the United States as a rational universe in which the physical needs to fight to find its place and to escape what fate has in store for it. Ali and Stephanie, our two characters, do not appear in the short stories, and Craig Davidson’s collection already seems to belong to the prehistory of the project, but the power and brutality of the tale, our desire to use drama, indeed melodrama, to magnify their characters all have their immediate source in those stories. -

A Prophet of Grace a Prophet of Grace an Expository'& Devotional Study of the Life of Elisha

A PROPHET OF GRACE A PROPHET OF GRACE AN EXPOSITORY'& DEVOTIONAL STUDY OF THE LIFE OF ELISHA BY THE REV. ALEXANDER STEWART EDINBURGH W. F. HENDERSON 19 GEORGE IV BRIDGE Prl,.ted t"n Great JJritain by T1<rnhull & Spears, Edinburgh TO THE CONGREGATION OF ST COLUMBA AND FOUNTAINBRIDGE FREE OHURCH, EDINBURGH THIS VOLUME IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED PREFACE THE following pages deal with a portion of the Old Testament Scriptures which can scarcely be supposed to offer any special attraction to the modern mind, and which therefore, as a matter of fact, is to a great extent neglected alike by preachers and by. writers on Bible themes. It is indeed not too much to say. that in many quarters to-day the claim that the recorded events of the life of Elisha should be regarded as serious history would be dismissed with a derisive smile as the survival of a discredited doctrine of Scripture. This attitude is of course due to the miraculous element which occupies so large a place in the narrative. In an age when a daring challenge is being offered to the miracles of Jesus Christ Himself, it is hardly to be expected that the marvels associated with a shadowy figure which looms out from the mists of a much more distant past should be accepted as literal historical happenings. In those far off days, we are told, men's minds were more credulous than they are in this scientific age ; they were accordingly disposed to invest with supernatural significance every phenomenon of the natural world which they were unable to understand ; and in this way a fertile soil was provided for the propagation of myth and legend. -

2015 WORLD CINEMA Duke of York’S the Brighton Film Festival 13-29 Nov 2015 OPENING NIGHT Fri 13 Nov / 8:30Pm

The Brighton Film Festival ADVENTURES IN 13-29 NOV 2015 WORLD CINEMA www.cine-city.co.uk Duke OF YORK’S The Brighton Film Festival 13-29 Nov 2015 OPENING NIGHT FRI 13 NOV / 8:30PM DIR: TODD Haynes. ADVENTURES IN WITH: Cate BLanchett, ROOney MARA, KYLE CHANDLER. WORLD CINEMA UK / USA 2015. 118 MINS. A stirring and stunningly realised adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s TH novel The Price of Salt, set in Welcome TO THE 13 EDITION OF CINECITY 1950s’ New York. Therese (Rooney Mara) is an aspiring photographer, working in a Manhattan department CINECITY presents the very best store where she first encounters (15) in world cinema with a global mix of Appropriately for our 13th edition, a strong coming-of- Ben Wheatley’s High Rise – both based on acclaimed Carol (Cate Blanchett), an alluring age theme runs right through this year’s selection with novels and with long and complicated paths to the older woman whose marriage is premieres and previews, treasures many titles featuring a young protagonist at their heart, screen - we have produced an updated version of ‘Not breaking down. There is an Carol from the archive, artists’ cinema, navigating their way in the world. Showing at this Cinema’, our programme of unrealised immediate connection between a showcase of films made in this British Cinema, which will be available at venues them but as their connection city and a programme of talks and Highlighted by the screenings of throughout the festival. deepens, a spiralling emotional The Forbidden Room, Hitchcock / intensity has seismic and far-reaching education events.