Jacques Audiard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film & Event Calendar

1 SAT 17 MON 21 FRI 25 TUE 29 SAT Events & Programs Film & Event Calendar 12:00 Event 4:00 Film 1:30 Film 11:00 Event 10:20 Family Gallery Sessions Tours for Fours: Art-Making Warm Up. MoMA PS1 Sympathy for The Keys of the #ArtSpeaks. Tours for Fours. Daily, 11:30 a.m. & 1:30 p.m. Materials the Devil. T1 Kingdom. T2 Museum galleries Education & 4:00 Film Museum galleries Saturdays & Sundays, Sep 15–30, Research Building See How They Fall. 7:00 Film 7:00 Film 4:30 Film 10:20–11:15 a.m. Join us for conversations and T2 An Evening with Dragonfly Eyes. T2 Dragonfly Eyes. T2 10:20 Family Education & Research Building activities that offer insightful and Yvonne Rainer. T2 A Closer Look for 7:00 Film 7:30 Film 7:00 Film unusual ways to engage with art. Look, listen, and share ideas TUE FRI MON SAT Kids. Education & A Self-Made Hero. 7:00 Film The Wind Will Carry Pig. T2 while you explore art through Research Building Limited to 25 participants T2 4 7 10 15 A Moment of Us. T1 movement, drawing, and more. 7:00 Film 1:30 Film 4:00 Film 10:20 Family Innocence. T1 4:00 Film WED Art Lab: Nature For kids age four and adult companions. SUN Dheepan. T2 Brigham Young. T2 This Can’t Happen Tours for Fours. SAT The Pear Tree. T2 Free tickets are distributed on a 26 Daily. Education & Research first-come, first-served basis at Here/High Tension. -

Benicio Del Toro Mathieu Amalric Psychotherapy of A

WHY NOT PRODUCTIONS PRESENTS BENICIO DEL TORO MATHIEU AMALRIC JIMMY P. PSYCHOTHERAPY OF A PLAINS INDIAN A FILM BY ARNAUD DESPLECHIN WHY NOT PRODUCTIONS PRESENTS BENICIO DEL TORO MATHIEU AMALRIC JIMMY P. PSYCHOTHERAPY OF A PLAINS INDIAN A FILM BY ARNAUD DESPLECHIN 2013 – France – 1h54 – 2.40 – 5.1 INTERNATIONAL SALES INTERNATIONAL PR THE PR CONTACT Phil SYMES - +33 (0)6 09 65 58 08 Carole BARATON - [email protected] Ronaldo MOURAO - +33 (0)6 09 56 54 48 Gary FARKAS - [email protected] [email protected] Vincent MARAVAL - [email protected] Silvia SIMONUTTI - [email protected] SYNOPSIS GEORGES DEVEREUX At the end of World War II, Jimmy Picard, a Native American Blackfoot who fought Inspired by a true story JIMMY P. (Psychotherapy of a Plains Indian) is adapted from the in France, is admitted to Topeka Military Hospital in Kansas - an institution specializing seminal book Reality and Dream by Georges Devereux. Published for the first time in in mental illness. Jimmy suffers from numerous symptoms: dizzy spells, temporary 1951, the book reflects the remarkable multidisciplinary talents of its writer, standing as blindness, hearing loss... and withdrawal. In the absence of any physiological causes, it does at a crossroads between anthropology and psychoanalysis, and opening the way he is diagnosed as schizophrenic. Nevertheless, the hospital management decides to ethno-psychiatry, among other disciplines. It is also the only book about psychoanalysis to seek the opinion of Georges Devereux, a French anthropologist, psychoanalyst to transcribe an entire analysis, session after session, in minute detail. and specialist in Native American culture. Georges Devereux, a Hungarian Jew, moved to Paris in the mid 1920s. -

12 Big Names from World Cinema in Conversation with Marrakech Audiences

The 18th edition of the Marrakech International Film Festival runs from 29 November to 7 December 2019 12 BIG NAMES FROM WORLD CINEMA IN CONVERSATION WITH MARRAKECH AUDIENCES Rabat, 14 November 2019. The “Conversation with” section is one of the highlights of the Marrakech International Film Festival and returns during the 18th edition for some fascinating exchanges with some of those who create the magic of cinema around the world. As its name suggests, “Conversation with” is a forum for free-flowing discussion with some of the great names in international filmmaking. These sessions are free and open to all: industry professionals, journalists, and the general public. During last year’s festival, the launch of this new section was a huge hit with Moroccan and internatiojnal film lovers. More than 3,000 people attended seven conversations with some legendary names of the big screen, offering some intense moments with artists, who generously shared their vision and their cinematic techniques and delivered some dazzling demonstrations and fascinating anecdotes to an audience of cinephiles. After the success of the previous edition, the Festival is recreating the experience and expanding from seven to 11 conversations at this year’s event. Once again, some of the biggest names in international filmmaking have confirmed their participation at this major FIFM event. They include US director, actor, producer, and all-around legend Robert Redford, along with Academy Award-winning French actor Marion Cotillard. Multi-award-winning Palestinian director Elia Suleiman will also be in attendance, along with independent British producer Jeremy Thomas (The Last Emperor, Only Lovers Left Alive) and celebrated US actor Harvey Keitel, star of some of the biggest hits in cinema history including Thelma and Louise, The Piano, and Pulp Fiction. -

Press Information September | October 2016 Choice of Arms The

Press Information September | October 2016 Half a century of modern French crime thrillers and Samuel Beckett and Buster Keaton 's collaboration of the century in the year of 1965; the politically aware work of documentary filmmaker Helga Reidemeister and the seemingly apolitical "hipster" cinema of the Munich Group between 1965 and 1970: these four topics will launch the 2016/17 season at the Austrian Film Museum. Furthermore, the Film Museum will once again take part in the Long Night of the Museums (October 1); a new semester of our education program School at the Cinema begins on October 13, and the upcoming publications ( Alain Bergala's book The Cinema Hypothesis and the DVD edition of Josef von Sternberg's The Salvation Hunters ) are nearing completion. Latest Film Museum restorations are presented at significant film festivals – most recently, Karpo Godina's wonderful "film-poems" (1970-72) were shown at the Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna – the result of a joint restoration project conducted with Slovenska kinoteka. As the past, present and future of cinema have always been intertwined in our work, we are particularly glad to announce that Michael Palm's new film Cinema Futures will have its world premiere at the Venice Film Festival on September 2 – the last of the 21 projects the Film Museum initiated on the occasion of its 50th anniversary in 2014. Choice of Arms The French Crime Thriller 1958–2009 To start off the season, the Film Museum presents Part 2 of its retrospective dedicated to French crime cinema. Around 1960, propelled by the growth spurt of the New Wave, the crime film was catapulted from its "classical" period into modernity. -

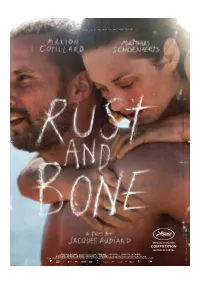

Marion Cotillard Matthias Schoenaerts RUST AND

RustnBone1.indd 1 6/5/12 15:12:51 Why Not Productions and Page 114 present Marion Cotillard Matthias Schoenaerts RUST AND BONE A film by Jacques Audiard Armand Verdure / Céline Sallette / Corinne Masiero Bouli Lanners / Jean-Michel Correia France / Belgium / 2012 / color / 2.40 / 120 min International Press: International Sales: Magali Montet Celluloid Dreams [email protected] 2, rue Turgot - 75009 Paris Tel: +33 6 71 63 36 16 Tel: +33 1 4970 0370 Fax: +33 1 4970 0371 Delphine Mayele [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +33 6 60 89 85 41 Contact in Cannes Celluloid Dreams 84, rue d’Antibes 06400 Cannes Hengameh Panahi +33 6 11 96 57 20 Annick Mahnert +33 6 37 12 81 36 Agathe Mauruc +33 6 82 73 80 04 Director’s Note There is something gripping about Craig Davidson’s short story collection “Rust and Bone”, a depiction of a dodgy, modern world in which individual lives and simple destinies are blown out of all proportion by drama and accident. They offer a vision of the United States as a rational universe in which the physical needs to fight to find its place and to escape what fate has in store for it. Ali and Stephanie, our two characters, do not appear in the short stories, and Craig Davidson’s collection already seems to belong to the prehistory of the project, but the power and brutality of the tale, our desire to use drama, indeed melodrama, to magnify their characters all have their immediate source in those stories. -

Thomas Vinterberg Film

LUC BESSON PRESENTS MATTHIAS LÉA COLIN SCHOENAERTS SEYDOUX FIRTH A THOMAS VINTERBERG FILM COMING SOON SYNOPSIS Kursk is inspired by the unforgettable true story of the K-141 Kursk, a Russian flagship nuclear-powered submarine that sank to the bottom of the Barents Sea in August 2000. As 23 sailors fought for survival aboard the disabled sub, their families desperately battled bureaucratic obstacles and impossible odds to find answers and save them. 2 THE KURSK TRAGEDY On August 10, 2000, Kursk — a submarine twice the size of a jumbo jet and longer than two football fields, the “unsinkable” pride of the Russian Navy’s Northern Fleet — embarked upon a naval exercise. It was their first exercise in a decade and the maneuvers entailed 30 ships and three submarines. Two days later, two internal explosions, powerful enough to register on seismographs as far away as Alaska, sent the ship to the bottom of the Arctic waters of the Barents Sea. At least 23 of the 118 sailors aboard survived the explosions. Over the next nine days, the entire world was on tenterhooks, as rescue operations faltered and foreign assistance was refused. The fate of the men aboard hung in the balance. Journalist Robert Moore’s book A Time to Die: The Untold Story of the Kursk Tragedy scrupulously dissects all the forensic evidence and every agonizing moment on the final hours in the lives of those doomed sailors. 3 PRODUCTION NOTES FROM BOOK TO SCREEN recalls. “But one thing that stayed with me, from the what happened. They all died. So we surrounded news coverage, was the tapping. -

Contemporary World Cinema Brian Owens, Artistic Diretor – Nashville Film Festival

Contemporary World Cinema Brian Owens, Artistic Diretor – Nashville Film Festival OLLI Winter 2015 Term Tuesday, January 13 Viewing Guide – The Cinema of Europe These suggested films are some that will or may come up for discussion during the first course. If you go to Netflix, you can use hyperlinks to find further suggestions. The year listed is the year of theatrical release in the US. Some films (Ida for instance) may have had festival premieres in the year prior. VOD is “Video On Demand.” Note: It is not necessary to see any or all of the films, by any means. These simply serve as a guide for the discussion. You can also use IMDB.com (Internet Movie Database) to search for other works by these filmmakers. You can also keep this list for future viewing after the session, if that is what you prefer. Most of the films are Rated R – largely for language and brief nudity or sexual content. I’ve noted in bold the films that contain scenes that could be too extreme for some viewers. In the “Additional works” lines, those titles are noted by an asterisk. Force Majeure Director: Ruben Östlund. 2014. Sweden. 118 minutes. Rated R. A family on a ski holiday in the French Alps find themselves staring down an avalanche during lunch. In the aftermath, their dynamic has been shaken to its core. Currently playing at the Belcourt. Also Available on VOD through most services and on Amazon Instant. Ida Director: Pawel Pawlikowski. 2014. Poland. 82 minutes. Rated PG-13. A young novitiate nun in 1960s Poland, is on the verge of taking her vows when she discovers a dark family secret dating back to the years of the Nazi occupation. -

December 2012 Table of Contents

NEWSLETTER DECEMBER 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table is hyperlinked to each article! WELCOME – by Martyn Sibley ...............................................................................................................................................................................................3 Differently abled through digital art .....................................................................................................................................................................................4 Viewing disability and difference through the eye of a lens ................................................................................................................................................7 Disability art and Turning Points ...........................................................................................................................................................................................9 Accessibility with style .........................................................................................................................................................................................................11 The British Paraorchestra: recruiting new talents ..............................................................................................................................................................13 Q&A with one-handed pianist Nicholas McCarthy .............................................................................................................................................................14 -

De Battre Mon Cœur S'est Arrêté Jacques Audiard

DE BATTRE MON CŒUR S’EST ARRÊTÉ JACQUES AUDIARD D E B A T T R E M O N C Œ U R S ‘ E S T A R R Ê T É J A C Q U E S A U D I A R D BASTIEN FERRÉ THOMAS STEINMETZ MAÎTRISER Auteurs Directeur de publication Jean-Marc Merriaux Bastien Ferré enseigne le cinéma, l’audiovisuel et les lettres au lycée Philippe-Lamour de Nîmes. Également réalisateur, il navigue Directrice de l’édition transmédia et de la pédagogie entre le court métrage de fiction (Aux marches du palais, 2011) et le Michèle Briziou documentaire (Un monde sous la main, 2014). Directeur artistique Thomas Steinmetz enseigne le cinéma et la littérature en première Samuel Baluret supérieure au lycée Jean-Pierre-Vernant de Sèvres, ainsi que l’espa- gnol à l’université Paris III-Sorbonne nouvelle. Il anime également Coordination éditoriale des débats littéraires au festival America de Vincennes, où il est par Carole Fouillen et Éric Rostand ailleurs interprète. Ses recherches portent sur les littératures et le cinéma néofan- Secrétariat d’édition tastiques, sur les relations entre littérature et cinéma et sur la Véronique Le Dosseur et Nathalie Bidart littérature hispano-américaine contemporaine. Iconographie Adeline Riou et Maxime Bissonnet Remerciements Les auteurs remercient chaleureusement Jacques Audiard pour son Crédits photographiques temps et son aimable contribution à l’ouvrage, Patrick Laudet Photogrammes du film De battre mon cœur s’est arrêté : et Marie-Laure Lepetit pour leur confiance, Carole Fouillen et © Why Not Productions l’ensemble de l’équipe éditoriale de Canopé, Fanny Perrigault et Anne Belle pour leurs conseils avisés et leur relecture éclairante. -

Community Exhibitor Survey

Community Exhibitor Survey 2018 — 2019 Table of Contents Table of Contents 1 Summary 2 Introduction 4 Background 4 Aims 4 Timescale 4 Sector 4 Methods 4 Results 5 Administration 6 Audience, Membership and Admission 8 Provision 13 Programming 15 Cinema For All 19 The Sector 24 1 Summary Survey The questionnaire was sent out to all full, associate and affiliate Cinema For All members and other community cinema organisations on the Cinema For All mailing list. 137 organisations responded to the survey. Administration • 80% of respondents were established in the year 2000 or later. • 82% of respondents describe themselves as a Community Cinema or Film Society. • Community Cinemas and Film Societies were seen as different by 60% of respondents, with the main cited differences being in administration (open vs membership organisations) and programming. • Staff or volunteers from just under two thirds (64%) of responding organisations attended an event aimed at film exhibitors. • 18% of respondents had paid members of staff. • Most respondents (80%) used just one venue for all of their screenings, and almost half (45%) of respondents’ primary venues were village halls or community centres. • Over a third (35%) of responding groups purchased equipment during the relevant period. Audience, Membership and Admission • The average audience size was 56, which is a decrease from 75 reported in both 2009 and 2014. • Despite the lower average audience size, admissions seem to have risen; the average total number of admissions this year was 2,383, up from 1,360 in 2009 and 1,891 in 2014. • Just 15% of groups reported a decrease in their audience size. -

1. Title: 13 Tzameti ISBN: 5060018488721 Sebastian, A

1. Title: 13 Tzameti ISBN: 5060018488721 Sebastian, a young man, has decided to follow instructions intended for someone else, without knowing where they will take him. Something else he does not know is that Gerard Dorez, a cop on a knife-edge, is tailing him. When he reaches his destination, Sebastian falls into a degenerate, clandestine world of mental chaos behind closed doors in which men gamble on the lives of others men. 2. Title: 12 Angry Men ISBN: 5050070005172 Adapted from Reginald Rose's television play, this film marked the directorial debut of Sidney Lumet. At the end of a murder trial in New York City, the 12 jurors retire to consider their verdict. The man in the dock is a young Puerto Rican accused of killing his father, and eleven of the jurors do not hesitate in finding him guilty. However, one of the jurors (Henry Fonda), reluctant to send the youngster to his death without any debate, returns a vote of not guilty. From this single event, the jurors begin to re-evaluate the case, as they look at the murder - and themselves - in a fresh light. 3. Title: 12:08 East of Bucharest ISBN: n/a 12:08pm on the 22 December 1989 was the exact time of Ceausescu's fall from power in Romania. Sixteen years on, a provincial TV talk show decides to commemorate the event by asking local heroes to reminisce about their own contributions to the revolution. But securing suitable guests proves an unexpected challenge and the producer is left with two less than ideal participants - a drink addled history teacher and a retired and lonely sometime-Santa Claus grateful for the company. -

Lynne Ramsay

Why Not Productions presents In association with Film4, BFI, Amazon Studios, Sixteen Films, JWFilms YOU WERE NEVER REALLY HERE A film by Lynne Ramsay Starring Joaquin Phoenix, Ekaterina Samsonov 95 min | UK | English | Color | Digital | 2.39 | 24fps | 5.1 International Sales International PR IMR Charles McDonald Vincent Maraval [email protected] Noëmie Devide +44 7785 246 377 [email protected] Kim Fox | Lesly Gross US PR Samantha Deshon Jeff Hill [email protected] [email protected] SYNOPSIS A missing teenage girl. A brutal and tormented enforcer on a rescue mission. Corrupt power and vengeance unleash a storm of violence that may lead to his awakening. LYNNE RAMSAY Director Born in Glasgow, Lynne Ramsay is considered one of the British most original and exciting voices working in Independent cinema today. She has a long running relationship with Cannes winning the Prix de Jury in 1996 for her graduation film, the short Small Deaths and in 1998 for her third short Gasman. Her debut feature film Ratcatcher premiered in Un Certain Regard (2000) winning Special Mention. We need to talk about Kevin was the only British film nominated for the Palme d'Or in official competition in 2011. It received several BAFTA nominations and won 'Best Director' at the British independent Film awards, 'Best film' at the London Film Festival and 'Best Screenplay' from the Writers Guild of Great Britain. Swimmer, commissioned by the Cultural Olympiad of Great Britain (2012), won the BAFTA (2013) for Best short film. JOAQUIN PHOENIX Actor Joaquin Phoenix began his acting career at the age of eight.