William Golding's Great Dream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paper XI: the 20Th Century Unit I Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness

1 Paper XI: The 20th Century Unit I Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness 1. Background 2. Plot Overview 3. Summary and Analysis 4. Character Analysis 5. Stylistic Devices of the Novel 6. Study Questions 7. Suggested Essay Topics 8. Suggestions for Further Reading 9. Bibliography Structure 1. Background 1.1 Introduction to the Author Joseph Conrad, one of the English language's greatest stylists, was born Teodor Josef Konrad Nalecz Korzenikowski in Podolia, a province of the Polish Ukraine. Poland had been a Roman Catholic kingdom since 1024, but was invaded, partitioned, and repartitioned throughout the late eighteenth-century by Russia, Prussia, and Austria. At the time of Conrad's birth (December 3, 1857), Poland was one-third of its size before being divided between the three great powers; despite the efforts of nationalists such as Tadeusz Kosciuszko, who led an unsuccessful uprising 2 in 1795, Poland was controlled by other nations and struggled for independence. When Conrad was born, Russia effectively controlled Poland. Conrad's childhood was largely affected by his homeland's struggle for independence. His father, Apollo Korzeniowski, belonged to the szlachta, a hereditary social class comprised of members of the landed gentry; he despised the Russian oppression of his native land. At the time of Conrad's birth, Apollo's land had been seized by the Russian government because of his participation in past uprisings. He and one of Conrad's maternal uncles, Stefan Bobrowski, helped plan an uprising against Russian rule in 1863. Other members of Conrad's family showed similar patriotic convictions: Kazimirez Bobrowski, another maternal uncle, resigned his commission in the army (controlled by Russia) and was imprisoned, while Robert and Hilary Korzeniowski, two fraternal uncles, also assisted in planning the aforementioned rebellion. -

Republic of Turkey Firat University Institute of Social Sciences Department of Western Languages and Literatures Program of English Language and Literature

REPUBLIC OF TURKEY FIRAT UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF WESTERN LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES PROGRAM OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE AN ECOCRITICAL READING OF THE INHERITORS BY WILLIAM GOLDING MASTER THESIS SUPERVISOR PREPARED BY Assist. Prof. Dr. Seda ARIKAN Emrah GÜMÜŞBOĞA ELAZIĞ - 2015 II ÖZET Yüksek Lisans Tezi William Golding’in The Inheritors Adlı Romanının Ekoeleştirel Bir İncelemesi Emrah GÜMÜŞBOĞA Fırat Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Batı Dilleri ve Edebiyatları Anabilim Dalı İngiliz Dili ve Edebiyatı Bilim Dalı Elazığ – 2015, Sayfa: V + 86 Bu çalışma William Golding’in The Inheritors adlı eserinde geçen doğa tasavvurunun ekoeleştirel bakış açısıyla tartışılmasını amaçlamaktadır. Giriş ve sonuç bölümleri ve dört ana bölümden oluşan çalışma, ekoeleştirinin ortaya çıkışını ve gelişim sürecini inceleyerek The Inheritors adlı romanda ekoleştirel öğelerin yansımasını ele almaktadır. William Golding’in dünya görüşünü ve insanoğluna bakış açısını yansıtan bu roman, günümüz ekoeleştirel söylemleri önceler niteliktedir. Bu bağlamda, insanoğlunun doğaya karşı yıkıcı eylemleri ve doğayı sömürü üzerine kurulu solipsist yaklaşımının ilksel örnekleri, arkaik bir dünyayı temsil eden bu romanda resmedilmektedir. Bu çalışma Golding’in resmettiği bu dünyayı ekoleştirel bir söylem olarak ortaya koymayı amaçlamaktadır. Anahtar Kelimeler: Ekoeleştiri, William Golding, The Inheritors , Neanderthals, Homo sapiens III ABSTRACT Master Thesis An Ecocritical Reading of The Inheritors by William Golding Emrah GÜMÜŞBOĞA Fırat University Institute of Social Sciences Department of Western Languages and Literatures Program of English Language and Literature Elazığ - 2015, Sayfa: V + 86 This study aims to discuss the concept of nature in William Golding’s novel The Inheritors through ecocritical approach. The study consisting of four main chapters with an introduction and a conclusion examines the rise and development of ecocriticism and addresses reflections of ecocritical elements in The Inheritors. -

William Golding's the Paper Men: a Critical Study درا : روا و ر ل ورق

William Golding’s The Paper Men: A Critical study روا و ر ل ورق : درا Prepared by: Laheeb Zuhair AL Obaidi Supervised by: Dr. Sabbar S. Sultan A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Master of Arts in English Language and Literature Department of English Language and Literature Faculty of Arts and Sciences Middle East University July, 2012 ii iii iv Acknowledgment I wish to thank my parent for their tremendous efforts and support both morally and financially towards the completion of this thesis. I am also grateful to thank my supervisor Dr. Sabbar Sultan for his valuable time to help me. I would like to express my gratitude to the examining committee members and to the panel of experts for their invaluable inputs and encouragement. Thanks are also extended to the faculty members of the Department of English at Middle East University. v Dedication I dedicate this thesis to my precious father; To my beloved mother; To my two little brothers; To my family, friends, and to all people who helped me complete this thesis. vi Table of contents Subject A Thesis Title I B Authorization II C Thesis Committee Decision III D Acknowledgment IV E Dedication V F Table of Contents VI G English Abstract VIII H Arabic Abstract IX Chapter One: Introduction 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 Golding and Gimmick 2 1.2 Use of Symbols 4 1.3 Golding’s Recurrent Theme (s) 5 1.4 The Relationship between Creative Writer and 7 Biographers or Critics 1.6 Golding’s Biography and Writings 8 1.7 Statement of the problem 11 1.8 Research Questions 11 1.9 Objectives of the study 12 1.10 Significance of the study 12 1.11 Limitations of the study 13 1.12 Research Methodology 14 Chapter Two: Review of Literature 2.0 Literature Review 15 Chapter Three: Discussion 3.0 Preliminary Notes 35 vii 3.1 The Creative Writer: Between Two Pressures 38 3.2 The Nature of Creativity: Seen from the Inside and 49 Outside Chapter Four 4.0 Conclusion 66 References 71 viii William Golding’s The Paper Men: A Critical Study Prepared by: Laheeb Zuhair AL Obaidi Supervised by: Dr. -

8Th Grade Packet 3 Lord of the Flies Phase 3 Distance Learning

Reading Comprehension Activities Directions: Until your Lord of the Flies novel arrives, complete the Animal Farm Choiceboard Activities. See attachment. Also, complete the Vocabulary and English Activities. Included is: Animal Farm Choice Board Independent Reading Choice Board Vocabulary for Success Book Pages: Lessons 10-13 English: Language Network-Chapter 4 Verbs Test Language Network: (at end of packet) Chapter 5 - Adjectives and Adverbs Practice Pages and Tests Chapter 6 Adectives and Adverbs Practice Pages and Tests Chapter 7 Verbals Practice Pages and Tests Novel Study Non-Digital Choice Menu – Animal Farm Directions: – You must complete at least four of the items. **See attachments for concept map and newscast graphic organizer. Thesis Character Study Thematic Study Summary Setting Create a summary of Design a comic strip that Create a concept map about Write a 3-minute Create a timeline of two chapters we focuses on Squealer’s what you learned about newscast summary on events leading up to studied. *One use of gaslighting and propaganda. See below. an event from your the Battle of paragraph summary propaganda to influence favorite chapter in the Cowshed. for each chapter. the other animals. novel. Each paragraph should contain a thesis and three supporting details. Character Study Substitution Drama Summary Character Study Create a poster on Create an alternate Write a one-page play about Write a two-paragraph Create a concept regular copy paper ending (typed or your favorite, least favorite, blog about the events map about the concerning Molly’s written-minimum of three or most interesting scene in any chapter from events in any reactions to the events paragraphs) for the from the book. -

William Golding List

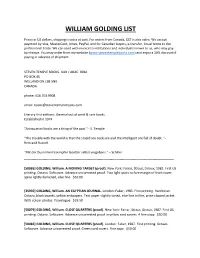

WILLIAM GOLDING LIST Prices in US dollars, shipping is extra at cost. For orders from Canada, GST is also extra. We accept payment by Visa, MasterCard, Amex, PayPal, and for Canadian buyers, e-transfer. Usual terms to the professional trade. We can send with invoice to institutions and individuals known to us, who may pay by cheque. You may order from my website (www.steventemplebooks.com) and enjoy a 10% discount if paying in advance of shipment. STEVEN TEMPLE BOOKS. ILAB / ABAC. IOBA PO BOX 45 WELLAND ON L3B 5N9 CANADA phone: 416.703.9908 email: [email protected] Literary first editions. General out of print & rare books. Established in 1974. "Antiquarian books are a thing of the past." - S. Temple “The trouble with the world is that the stupid are cocksure and the intelligent are full of doubt. “- Bertrand Russell "Mit der Dummheit kaempfen Goetter selbst vergebens." – Schiller ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- [50085] GOLDING, William. A MOVING TARGET (proof). New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1982. First US printing. Octavo. Softcover. Advance uncorrected proof. Two light spots to fore margin of front cover, spine lightly darkened, else fine. $50.00 [35930] GOLDING, William. AN EGYPTIAN JOURNAL. London: Faber, 1985. First printing. Hardcover. Octavo, black boards, yellow endpapers. Text paper slightly toned, else fine in fine, price-clipped jacket. With colour photos. Travelogue. $19.50 [50079] GOLDING, William. CLOSE QUARTERS (proof). New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1987. First US printing. Octavo. Softcover. Advance uncorrected proof in yellow card covers. A fine copy. $50.00 [50083] GOLDING, William. CLOSE QUARTERS (proof). London: Faber, 1987. First printing. -

The Scorpion God: Three Short Novels William Golding

The Scorpion God: Three Short Novels William Golding 178 pages William Golding 1984 The Scorpion God: Three Short Novels 0156796589, 9780156796583 Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1984 Three short novels show Golding at his subtle, ironic, mysterious best. The Scorpion God depicts a challenge to primal authority as the god-ruler of an ancient civilization lingers near death. Clonk Clonk is a graphic account of a crippled youth's triumph over his tormentors in a primitive matriarchal society. Envoy Extraordinary is a tale of Imperial Rome where the emperor loves his illegitimate son more than his own arrogant, loutish heir. file download wuxin.pdf Sequel to: Close quarters Fiction ISBN:0374526389 Dec 1, 1999 313 pages William Golding Fire Down Below Sequel to: Rites of passage. Recounts the further adventures of the eighteenth-century fighting ship, converted at the close of the Napoleonic War to carry passengers and cargo Dec 1, 1999 281 pages Fiction ISBN:0374526362 William Golding Close Quarters Scorpion Jorge Luis Borges, Donald A. Yates, James East Irby Selected Stories & Other Writings A new edition of a classic work by a late forefront Argentinean writer features the 1964 augmented original text and is complemented by a biographical essay, a tribute to the 1964 Fiction ISBN:0811216993 Labyrinths 256 pages download Domestics Michle Desbordes A Story 2003 149 pages ISBN:0571210066 The Maid's Request At the behest of the French king the artist has journeyed from Italy to lead his school of students in the design and construction of a chateau in the Loire Valley. Despite the Oct 1, 1999 Fiction William Golding 278 pages Edmund Talbot recounts his voyage from England to the Antipodes, and the humiliating confrontation between the stern Captain Anderson and the nervous parson, James Colley Rites of Passage ISBN:9780374526405 Short ISBN:0143027980 Asia Now reissued with a substantial new afterword, this highly acclaimed overview of Western attitudes towards the East has become one of the canonical texts of cultural studies Orientalism 2006 416 pages Edward W. -

Moral Sub-Structures As the Foundation of William Golding's

www.ijcrt.org © 2021 IJCRT | Volume 9, Issue 2 February 2021 | ISSN: 2320-2882 Moral Sub-structures as the Foundation of William Golding’s Novels LESHVEER SINGH RESEARCH SCHOLAR M.J.P.R.K.U. BAREILLY INDIA ANURADHA SINGH ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR Dept. OF ENGLISH, GOKULDAS H. G. PG COLLEGE MORADABAD INDIA. In Golding’s words we are a species that produces evil as a bee produces honey. Naturally as humble insects produce harmony and sweetness, we produce the wickedness and violence which spoils our lives. The purpose of Golding’s writing is not say-sex or geometry. It is just understanding. The understanding of ‘terrible disease’ and to rouse an alertness amids people and help in making this universe a paradise which man seems to have lost. Each and every novel of Golding searches the predicament of human life which is full of decay and fall due to the original sin committed by our first parents Adam and Eve. He is strongly adhere to the biblical term ‘idolatry’. By this man isolates himself off from the Supreme power whom we called God. My aim is to point out the ‘truths’ and probes the different state of human mind and also religious concerns hidden in the mighty lines of William Golding’s novels. Like the plays of Shakespeare, the novels of Golding serving its purpose of filling the faith into human mind which has gone a long long ago. The novels of Golding, namely, ‘Lord of the Flies’, ‘The Inheritors’, ‘Pincher Martin’ and ‘Free Fall’ are worth mentioning in this connection. -

Novels of William Golding: an Overview

NOVELS OF WILLIAM GOLDING: AN OVERVIEW DR. NAGNATH TOTAWAD Associate Prof., Dept. of English, Member, BOS in English, Coordinator, IGNOU, SC 1610, Vivekanand Arts, S.D.Commerce & Science College, Aurangabad, 431001 (MS) INDIA William Golding is known as a prominent writer of English fiction. He is judged as an incredible fabulist, a symbolic essayist or a mythmaker. In this regard his inclination is to be called as an author of 'mytho poetic control'. His books are translated in the light of philosophy. Golding’s vision about human instinct is very well reflected in his fictions, in a general sense he has confidence in God, yet he questions if God has faith in him or in humankind. His fictions are brimming with Christian imagery yet he bids to each sort of faith in his fiction. His propensity is toward the submissive and the soul. He never endeavors to instruction. There is no agreement in his fiction. He opens human instinct for the reader so well that the reader is stunned subsequent to perusing any Golding epic and starts to scrutinize his own tendency and his job in the unceasing catastrophe on the earth-organize. Keywords: Imagery, Christ, good, evil, loss, innocence, chaos, experience etc. INTRODUCTION William Golding was a great theological novelist. Golding’s work tries to achieve apt definition of the religious implications such as the sense of guilt and shame on the one hand and as the result of wars, and inevitable urgency of more humanity, more care and more love on the other. Golding has seen the cruelty and wickedness during his service in Navy, DR. -

William G. Golding

Bibliothèque Nobel 1983 Bernhard Zweifel William G. Golding Année de naissance 1911 Année du décès 1993 Langue anglais Raison: for his novels which, with the perspicuity of realistic narrative art and the diversity and universality of myth, illuminate the human condition in the world of today Informations supplementaire Littérature secondaire - R. A. Gekoski & P. A. Grogan, William Golding (1994) - Robert Fricker, Der späte William Golding, Schweiz. Monatsh. 70 (3), 233 (1990) - Robert Fricker, Der späte William Golding, Schweiz. Monatshefte 70, Nr. 3 (1990) - I. Gregor and M. Kinkead-Weekes, William Golding: a Critical Study (1967) - H.S. Babb, The Novels of William Golding (1973) - J. Whitley, W. Golding: Lord of the Flies (1970) - S. Medcalf, William Golding (1975) - J.I. Biles and R.D. Evans (eds.), William Golding: Some Critical Considerations (1978) - Philip Redpath, William Golding: A Structural Reading of His Fiction (1987) - L.KL. Dickson, The Modern Allegories of William Goldman (1990) - Lawrence S. Friedman, William Golding (1992) - Pralhad A. Kulkarni, William Golding (1994) - Karin Siegl, The Robinsonade Tradition in Robert Michael Ballantyne's the Coral Island and William Golding's the Lord of the Flies (1996) - Clarice Swisher, Readings on Lord of the Flies (1997) - David L. Hoover, Language and Style in the Inheritors (1998) Film - Lord of the flies, 1963, dir. By Peter Brook; remake 1990, directed for American tv-savvy kids Catalogue des oeuvres The Scorpion God [1971] Drame Envoy Extraordinary [1971] Clonk Clonk [1971] -

Palacký University Olomouc Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies

Palacký University Olomouc Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies William Golding’s Trinity: Humanity, Society, and Religion as the Building Blocks of Humankind’s Self-delusion Master Thesis Bc. Čeněk Cvešper F170474 English Philology Supervisor: Mgr. Ema Jelínková, Ph.D. Olomouc 2020 Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto diplomovou práci vypracoval samostatně pod odborným dohledem vedoucího práce a uvedl jsem všechny použité podklady a literaturu. V Olomouci dne 19.2.2020 …….………………………………. Čeněk Cvešper Děkuji Mgr. Emě Jelínkové, Ph.D. za pomoc při vypracování této práce a za poskytnutí odborných materiálů a cenných rad. Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................... 4 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 5 2. The life of William Golding .................................................................................................... 8 3. The human condition .......................................................................................................... 14 4. Of religions and saints ......................................................................................................... 29 5. The social clockwork ........................................................................................................... 44 6. Conclusion .......................................................................................................................... -

William Golding: the Man Who Wrote Lord of the Flies Pdf, Epub, Ebook

WILLIAM GOLDING: THE MAN WHO WROTE LORD OF THE FLIES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John Carey | 592 pages | 03 Sep 2009 | FABER & FABER | 9780571231638 | English | London, United Kingdom William Golding: The Man Who Wrote Lord of the Flies PDF Book The day before he died at 81 he was up a ladder unblocking a drainpipe. Drawing on a vast wealth of previously-unpublished material in the Golding family archive, John Carey explores the life and career of an often violently self-critical novelist who won the nobel prize for literature. John Carey has an extensive and impressive list of sources at the end of the biography. In reading this biography, I learned something of other characters, like James Lovelock, who lived for a time in the same Wiltshire village as William Golding. If you love the novels of William Golding then this first biography of the great writer will fascinate you. With Carey it's part of his integrity. John Carey. His time in the trenches gave him the insight he needed to create believable archetypes. Aug 07, Betsy rated it really liked it. He feels happy and unafraid. Welcome back. And it was largely written to serve as comfort, which helps explain its warmth: Rites of Passage to offset the difficulty of Darkness Visible and Close Quarters in the same relation to The Paper Men. Extensive use is made of his journals and letters to produce a warts'n all bio. But for him Golding would probably have died an unknown schoolteacher. As a long-time admirer of Golding, Carey can't have believed his luck when given access to a family archive containing several unpublished novels, two autobiographies, and a 5,page private journal. -

William Golding: a Process of Discovery

WILLIAM GOLDING: A PROCESS OF DISCOVERY APPROVED: 1- Ma joi/ Professor Consulting E*?ofessor Mine# Professor {•9 • f Chairman of the Department of English Dean <5f the Graduate School WILLIAM GOLDING: A PROCESS OF DISCOVERY THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Diane M, Dodson, B. A, Denton.9 Texas Augus t j 1970 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 11 • LORD OF THE FLIES 12 III. THE INHERITORS 38 IV. PIN CHER MARTIN AND FREE FALL 60 V. THE SPIRE 84 VI. THE PYRAMID 106 VII. CONCLUSION. 123 A SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY . 129 HI CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION The scholar who is especially interested in the influence of a writer's life and intellectual background on his literature would probably find William Golding's biography a sheer delight because almost all that is known about Golding's life and interests can easily be traced in his novels. Golding spent a rather isolated childhood during which he read simultaneously the great classics of childhood and adulthood. He recalls with equal enthusiasm the first i time he read the works of Ballantyne, Burroughs, and Verne, 2 and Homer, Sophocles, and Euripides. Among his favorite memories of his youth is his passion for the written word and for words themselves: While I was supposed to be learning my Collect, I was likely to be chanting inside my head a list of delightful words which I had picked up God knows where--deebriss and Skirmishar, creskertt and sweeside.3 "'"William Golding, "Billy the Kid," The Hot Gates (New York, 1965), pp.