Golding As a Psychological Novelist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Writing from Ireland

New Writing from Ireland Promoting Irish Literature Abroad Fiction | 1 NEW WRITING FROM ireLAND 2013 This is a year of new beginnings – Ireland first published 2013 Impac Award-winner Literature Exchange has moved offices Kevin Barry’s collection, There Are Little and entered into an exciting partnership Kingdoms in 2007, offers us stories from with the Centre for Literary Translation at Colin Barrett. Trinity College, Dublin. ILE will now have more space to host literary translators from In the children and young adult section we around the world and greater opportunities have debut novels by Katherine Farmar and to organise literary and translation events Natasha Mac a’Bháird and great new novels in co-operation with our partners. by Oisín McGann and Siobhán Parkinson. Writing in Irish is also well represented and Regular readers of New Writing from Ireland includes Raic/Wreck by Máire Uí Dhufaigh, will have noticed our new look. We hope a thrilling novel set on an island on the these changes make our snapshot of Atlantic coast. contemporary Irish writing more attractive and even easier to read! Poetry and non-fiction are included too. A new illustrated book of The Song of Contemporary Irish writing also appears Wandering Aengus by WB Yeats is an exciting to be undergoing a renaissance – a whole departure for the Futa Fata publishing house. 300 pp range of intriguing debut novels appear Leabhar Mór na nAmhrán/The Big Book of this year by writers such as Ciarán Song is an important compendium published Collins, Niamh Boyce, Paul Lynch, Frank by Cló Iar-Chonnacht. -

Department of English and American Studies English Language And

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Bc. Michaela Murajdová Unheard Voices, Lost Children and the Ambivalence of Power in Selected Rewritings of Master Narratives Master’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Martina Horáková, Ph.D. 2015 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Bc. Michaela Murajdová Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor, Mgr. Martina Horáková, Ph.D., for her ecouragement during the writing process, her patience and numerous inspirational remarks. I would also like to thank my friends and my parents for their continuous support during the years of my studies and their unending love. Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................5 1. Questioning Metanarratives as a Strategy of Postcolonial and Feminist Discourse .....................................................................................................8 2. Taking My Story Back: Giving Voice to the Marginalized ..................13 2.1. Female Perspective .........................................................................13 2.2. Gaps and Silences: Voices of the Doubly Colonized ......................21 3. Lost Children ........................................................................................29 4. Ambivalence of Power ..........................................................................45 -

2015 April Highlights

WHRO-TV Highlights April 2015 Nova “Alien Planets Revealed” Wednesday, April 1, 2015, 8:00-9:00 p.m. ASA’s planet-hunting Kepler Telescope has discovered thousands of exotic new worlds far beyond our solar system. Are any of them like Earth? And what sort of life could flourish on them? With vivid animation and input from expert astrophysicists and astrobiologists, NOVA takes you on a mind-bending exploration of these strange worlds and the possible creatures we might one day encounter there. Cancer the Emperor of all Maladies “Finding the Achilles Heel” Wednesday, April 1, 2015, 9:00-11:00 p.m. This episode starts at a moment of optimism: Scientists believe they have cracked the mystery of the malignant cell, and the first targeted therapies have been developed. But very quickly cancer reveals new layers of complexity and a formidable array of defenses. Many call for a new focus on prevention and early detection as the most promising fronts in the war on cancer. By the second decade of the 2000s, the bewildering complexity of the cancer cell yields to a more ordered picture, revealing new vulnerabilities and avenues of attack. Perhaps most exciting is the prospect of harnessing the human immune system to defeat cancer. A 60-year-old NASCAR mechanic with melanoma and a six-year-old with leukemia are pioneers in new immunotherapy treatments, which the documentary follows as their stories unfold. A Chef’s Life, Season 2 “The Fish Episode, Y’all” Thursday, April 2, 2015, 9:00-9:30 p.m. Vivian presents a few of the many ways fish makes its appearance in southern cooking. -

Both Gordimer and Coetzee Have Been Preoccupied, Throughout Their Careers, with the Responsibility of the Novelist

Volume 2: 2009-2010 ISSN: 2041-6776 9 { Both Gordimer and Coetzee have been preoccupied, throughout their careers, with the responsibility of the novelist. From your reading of the novels, how would you say their ideas about responsibility differ? Hamish Matthews Considering the responsibility of the novelist in South Africa involves questions deeply embedded in the country's troubled history. The spectre of apartheid casts an unavoidable shadow over writers from white privileged society despite the breakdown of the political system of apartheid. With regard to the problem of the author's position Gallagher queries, ”how one can write for œ in support of œ the ”Other‘ without presuming to write for œ assuming power over œ the Other.‘ 1 The ”Other‘ is a term used to refer to the black majority, in that they had been so suppressed by apartheid, that their sudden integration into South African culture did not erase the ingrained difference projected during apartheid between the ”us‘ and ”them‘ of whites and blacks. There are two extremes in which the racist hierarchy can live on through art. In speaking for the ”Other‘ there is a risk of a continuing form of linguistic colonialism. At the other end of the scale is the counter-fear of an outright refusal to deal with the ”Other‘, accepting unbridgeable differences, straying toward recreating the rhetoric that formed apartheid. It is between these two fears that Coetzee and Gordimer carefully tread. Coetzee leans strongly towards the impossibility of representation, pushing language to its limit to expose the limitations of current literary conditions. -

Paul and the Vocation of Israel: How Paul's Jewish Identity Informs His Apostolic Ministry, with Special Reference to Romans

Durham E-Theses Paul and the Vocation of Israel: How Paul's Jewish Identity Informs his Apostolic Ministry, with Special Reference to Romans WINDSOR, LIONEL JAMES How to cite: WINDSOR, LIONEL JAMES (2012) Paul and the Vocation of Israel: How Paul's Jewish Identity Informs his Apostolic Ministry, with Special Reference to Romans , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3920/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Paul and the Vocation of Israel: How Paul’s Jewish Identity Informs his Apostolic Ministry, with Special Reference to Romans by Lionel James Windsor Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Durham University Department of Theology and Religion 2012 Lionel James Windsor, “Paul and the Vocation of Israel: How Paul’s Jewish Identity Informs his Apostolic Ministry, with Special Reference to Romans,” Thesis, Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Durham University, Department of Theology and Religion, 2012. -

Lord of the Flies About the Author (William Golding) Born in Cornwall

Lord of the Flies About the Author (William Golding) ➢ Born in Cornwall on 19th September 1911. ➢ He attended Marlborough Grammar School, then went to Oxford with the intention of reading science but eventually graduated in English in 1933. ➢ He became a teacher. ➢ In 1939 he married Ann Brookfield and a year later volunteered for the Royal Navy in which he served until 1945. ➢ He had witnessed the two World Wars, the First World War as a child while in WWII, he participated in action. He took part in the D-Day landings in Normandy and rose to the rank of the lieutenant. ➢ After the War ended, he returned back to teaching taking up a job at Bishop Wordsworth’s School, Salisbury and after his superannuation he became a full time author. ➢ Lord of the Flies (1954) in his first published novel and it was made into a film in 1963. ➢ His other notable publications include The Inheritors (1955), Pincher Martin (1956), The Brass Butterfly (1958), Free Fall (1959), The Spire (1964), The Hot Gates (1965), The Pyramid (1967), The Scorpion God (1971), Darkness Visible (1979), Rites of Passage (1980), A Moving Target (1982) and The Paper Man (1984). ➢ He won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize and The Booker McConnell Prize in 1980 and won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1983. ➢ He died on 19th June, 1993 at the age of 81 years. Possible Sources of the novel Although the adventure-island-story tradition can be traced back to a host of novels like R.L. Stevenson’s Treasure Island, Arthur Ransome’s Swallows and Amazons, Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, yet the most notable influence had been R.M. -

Paper XI: the 20Th Century Unit I Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness

1 Paper XI: The 20th Century Unit I Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness 1. Background 2. Plot Overview 3. Summary and Analysis 4. Character Analysis 5. Stylistic Devices of the Novel 6. Study Questions 7. Suggested Essay Topics 8. Suggestions for Further Reading 9. Bibliography Structure 1. Background 1.1 Introduction to the Author Joseph Conrad, one of the English language's greatest stylists, was born Teodor Josef Konrad Nalecz Korzenikowski in Podolia, a province of the Polish Ukraine. Poland had been a Roman Catholic kingdom since 1024, but was invaded, partitioned, and repartitioned throughout the late eighteenth-century by Russia, Prussia, and Austria. At the time of Conrad's birth (December 3, 1857), Poland was one-third of its size before being divided between the three great powers; despite the efforts of nationalists such as Tadeusz Kosciuszko, who led an unsuccessful uprising 2 in 1795, Poland was controlled by other nations and struggled for independence. When Conrad was born, Russia effectively controlled Poland. Conrad's childhood was largely affected by his homeland's struggle for independence. His father, Apollo Korzeniowski, belonged to the szlachta, a hereditary social class comprised of members of the landed gentry; he despised the Russian oppression of his native land. At the time of Conrad's birth, Apollo's land had been seized by the Russian government because of his participation in past uprisings. He and one of Conrad's maternal uncles, Stefan Bobrowski, helped plan an uprising against Russian rule in 1863. Other members of Conrad's family showed similar patriotic convictions: Kazimirez Bobrowski, another maternal uncle, resigned his commission in the army (controlled by Russia) and was imprisoned, while Robert and Hilary Korzeniowski, two fraternal uncles, also assisted in planning the aforementioned rebellion. -

Republic of Turkey Firat University Institute of Social Sciences Department of Western Languages and Literatures Program of English Language and Literature

REPUBLIC OF TURKEY FIRAT UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF WESTERN LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES PROGRAM OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE AN ECOCRITICAL READING OF THE INHERITORS BY WILLIAM GOLDING MASTER THESIS SUPERVISOR PREPARED BY Assist. Prof. Dr. Seda ARIKAN Emrah GÜMÜŞBOĞA ELAZIĞ - 2015 II ÖZET Yüksek Lisans Tezi William Golding’in The Inheritors Adlı Romanının Ekoeleştirel Bir İncelemesi Emrah GÜMÜŞBOĞA Fırat Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Batı Dilleri ve Edebiyatları Anabilim Dalı İngiliz Dili ve Edebiyatı Bilim Dalı Elazığ – 2015, Sayfa: V + 86 Bu çalışma William Golding’in The Inheritors adlı eserinde geçen doğa tasavvurunun ekoeleştirel bakış açısıyla tartışılmasını amaçlamaktadır. Giriş ve sonuç bölümleri ve dört ana bölümden oluşan çalışma, ekoeleştirinin ortaya çıkışını ve gelişim sürecini inceleyerek The Inheritors adlı romanda ekoleştirel öğelerin yansımasını ele almaktadır. William Golding’in dünya görüşünü ve insanoğluna bakış açısını yansıtan bu roman, günümüz ekoeleştirel söylemleri önceler niteliktedir. Bu bağlamda, insanoğlunun doğaya karşı yıkıcı eylemleri ve doğayı sömürü üzerine kurulu solipsist yaklaşımının ilksel örnekleri, arkaik bir dünyayı temsil eden bu romanda resmedilmektedir. Bu çalışma Golding’in resmettiği bu dünyayı ekoleştirel bir söylem olarak ortaya koymayı amaçlamaktadır. Anahtar Kelimeler: Ekoeleştiri, William Golding, The Inheritors , Neanderthals, Homo sapiens III ABSTRACT Master Thesis An Ecocritical Reading of The Inheritors by William Golding Emrah GÜMÜŞBOĞA Fırat University Institute of Social Sciences Department of Western Languages and Literatures Program of English Language and Literature Elazığ - 2015, Sayfa: V + 86 This study aims to discuss the concept of nature in William Golding’s novel The Inheritors through ecocritical approach. The study consisting of four main chapters with an introduction and a conclusion examines the rise and development of ecocriticism and addresses reflections of ecocritical elements in The Inheritors. -

William Golding's the Paper Men: a Critical Study درا : روا و ر ل ورق

William Golding’s The Paper Men: A Critical study روا و ر ل ورق : درا Prepared by: Laheeb Zuhair AL Obaidi Supervised by: Dr. Sabbar S. Sultan A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Master of Arts in English Language and Literature Department of English Language and Literature Faculty of Arts and Sciences Middle East University July, 2012 ii iii iv Acknowledgment I wish to thank my parent for their tremendous efforts and support both morally and financially towards the completion of this thesis. I am also grateful to thank my supervisor Dr. Sabbar Sultan for his valuable time to help me. I would like to express my gratitude to the examining committee members and to the panel of experts for their invaluable inputs and encouragement. Thanks are also extended to the faculty members of the Department of English at Middle East University. v Dedication I dedicate this thesis to my precious father; To my beloved mother; To my two little brothers; To my family, friends, and to all people who helped me complete this thesis. vi Table of contents Subject A Thesis Title I B Authorization II C Thesis Committee Decision III D Acknowledgment IV E Dedication V F Table of Contents VI G English Abstract VIII H Arabic Abstract IX Chapter One: Introduction 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 Golding and Gimmick 2 1.2 Use of Symbols 4 1.3 Golding’s Recurrent Theme (s) 5 1.4 The Relationship between Creative Writer and 7 Biographers or Critics 1.6 Golding’s Biography and Writings 8 1.7 Statement of the problem 11 1.8 Research Questions 11 1.9 Objectives of the study 12 1.10 Significance of the study 12 1.11 Limitations of the study 13 1.12 Research Methodology 14 Chapter Two: Review of Literature 2.0 Literature Review 15 Chapter Three: Discussion 3.0 Preliminary Notes 35 vii 3.1 The Creative Writer: Between Two Pressures 38 3.2 The Nature of Creativity: Seen from the Inside and 49 Outside Chapter Four 4.0 Conclusion 66 References 71 viii William Golding’s The Paper Men: A Critical Study Prepared by: Laheeb Zuhair AL Obaidi Supervised by: Dr. -

8Th Grade Packet 3 Lord of the Flies Phase 3 Distance Learning

Reading Comprehension Activities Directions: Until your Lord of the Flies novel arrives, complete the Animal Farm Choiceboard Activities. See attachment. Also, complete the Vocabulary and English Activities. Included is: Animal Farm Choice Board Independent Reading Choice Board Vocabulary for Success Book Pages: Lessons 10-13 English: Language Network-Chapter 4 Verbs Test Language Network: (at end of packet) Chapter 5 - Adjectives and Adverbs Practice Pages and Tests Chapter 6 Adectives and Adverbs Practice Pages and Tests Chapter 7 Verbals Practice Pages and Tests Novel Study Non-Digital Choice Menu – Animal Farm Directions: – You must complete at least four of the items. **See attachments for concept map and newscast graphic organizer. Thesis Character Study Thematic Study Summary Setting Create a summary of Design a comic strip that Create a concept map about Write a 3-minute Create a timeline of two chapters we focuses on Squealer’s what you learned about newscast summary on events leading up to studied. *One use of gaslighting and propaganda. See below. an event from your the Battle of paragraph summary propaganda to influence favorite chapter in the Cowshed. for each chapter. the other animals. novel. Each paragraph should contain a thesis and three supporting details. Character Study Substitution Drama Summary Character Study Create a poster on Create an alternate Write a one-page play about Write a two-paragraph Create a concept regular copy paper ending (typed or your favorite, least favorite, blog about the events map about the concerning Molly’s written-minimum of three or most interesting scene in any chapter from events in any reactions to the events paragraphs) for the from the book. -

William Golding List

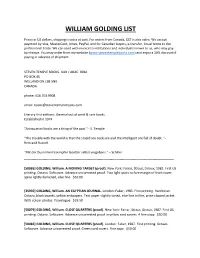

WILLIAM GOLDING LIST Prices in US dollars, shipping is extra at cost. For orders from Canada, GST is also extra. We accept payment by Visa, MasterCard, Amex, PayPal, and for Canadian buyers, e-transfer. Usual terms to the professional trade. We can send with invoice to institutions and individuals known to us, who may pay by cheque. You may order from my website (www.steventemplebooks.com) and enjoy a 10% discount if paying in advance of shipment. STEVEN TEMPLE BOOKS. ILAB / ABAC. IOBA PO BOX 45 WELLAND ON L3B 5N9 CANADA phone: 416.703.9908 email: [email protected] Literary first editions. General out of print & rare books. Established in 1974. "Antiquarian books are a thing of the past." - S. Temple “The trouble with the world is that the stupid are cocksure and the intelligent are full of doubt. “- Bertrand Russell "Mit der Dummheit kaempfen Goetter selbst vergebens." – Schiller ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- [50085] GOLDING, William. A MOVING TARGET (proof). New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1982. First US printing. Octavo. Softcover. Advance uncorrected proof. Two light spots to fore margin of front cover, spine lightly darkened, else fine. $50.00 [35930] GOLDING, William. AN EGYPTIAN JOURNAL. London: Faber, 1985. First printing. Hardcover. Octavo, black boards, yellow endpapers. Text paper slightly toned, else fine in fine, price-clipped jacket. With colour photos. Travelogue. $19.50 [50079] GOLDING, William. CLOSE QUARTERS (proof). New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1987. First US printing. Octavo. Softcover. Advance uncorrected proof in yellow card covers. A fine copy. $50.00 [50083] GOLDING, William. CLOSE QUARTERS (proof). London: Faber, 1987. First printing. -

The Scorpion God: Three Short Novels William Golding

The Scorpion God: Three Short Novels William Golding 178 pages William Golding 1984 The Scorpion God: Three Short Novels 0156796589, 9780156796583 Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1984 Three short novels show Golding at his subtle, ironic, mysterious best. The Scorpion God depicts a challenge to primal authority as the god-ruler of an ancient civilization lingers near death. Clonk Clonk is a graphic account of a crippled youth's triumph over his tormentors in a primitive matriarchal society. Envoy Extraordinary is a tale of Imperial Rome where the emperor loves his illegitimate son more than his own arrogant, loutish heir. file download wuxin.pdf Sequel to: Close quarters Fiction ISBN:0374526389 Dec 1, 1999 313 pages William Golding Fire Down Below Sequel to: Rites of passage. Recounts the further adventures of the eighteenth-century fighting ship, converted at the close of the Napoleonic War to carry passengers and cargo Dec 1, 1999 281 pages Fiction ISBN:0374526362 William Golding Close Quarters Scorpion Jorge Luis Borges, Donald A. Yates, James East Irby Selected Stories & Other Writings A new edition of a classic work by a late forefront Argentinean writer features the 1964 augmented original text and is complemented by a biographical essay, a tribute to the 1964 Fiction ISBN:0811216993 Labyrinths 256 pages download Domestics Michle Desbordes A Story 2003 149 pages ISBN:0571210066 The Maid's Request At the behest of the French king the artist has journeyed from Italy to lead his school of students in the design and construction of a chateau in the Loire Valley. Despite the Oct 1, 1999 Fiction William Golding 278 pages Edmund Talbot recounts his voyage from England to the Antipodes, and the humiliating confrontation between the stern Captain Anderson and the nervous parson, James Colley Rites of Passage ISBN:9780374526405 Short ISBN:0143027980 Asia Now reissued with a substantial new afterword, this highly acclaimed overview of Western attitudes towards the East has become one of the canonical texts of cultural studies Orientalism 2006 416 pages Edward W.