Songs of Love August 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alban Berg – Sieben Frühe Lieder

DOI: 10.2478/ajm-2020-0012 Studies Alban Berg – Sieben frühe Lieder. Performance perspectives IONELA BUTU, Associate Professor PhD “George Enescu” National University of Arts ROMANIA∗ Bergʼs worldwide reputation had been consolidated with orchestral and chamber works and the opera Wozzeck. (...) For different reasons, his dimension as a composer of songs does not seem to be very large, and yet it is fundamental to his personality nevertheless. Mark DeVoto Abstract: The study presents several interpretative suggestions made from the perspective of the accompanying pianist that played Alban Bergʼs Sieben frühe Lieder. Why this topic? Because in the Romanian music literature, there is nothing written about the song cycle Sieben frühe Lieder by Alban Berg, which is a representative work in the history of the art song. The theme, addressed in the literature written abroad, is treated mostly from a musicological standpoint. That is why we considered it useful to make some observations of an interpretative nature. They will become relevant if read in parallel with the PhD thesis entitled Alban Bergʼs “Sieben frühe Lieder”: An Analysis of Musical Structures and Selected Performances, written by Lisa A. Lynch (the only documentary source that proposes in-depth syntactic analyses of the work, associated with valuable interpretative suggestions made from a vocal perspective). We also considered useful, during the study, the comparison between the two variants of the work: the chamber/voice-piano version and the orchestral version. The analysis of the symphonic text was carried out intending the observation of significant details useful for realizing an expressive duo performance. Of course, our interpretative suggestions are a variant between many others. -

Preview Notes • Week Four • Persons Auditorium

2019 Preview Notes • Week Four • Persons Auditorium Saturday, August 3 at 8:00pm Sieben frühe Lieder (1905-08) Dolce Cantavi (2015) Alban Berg Caroline Shaw Born February 9, 1885 Born August 1, 1982 Died December 24, 1935 Duration: approx. 3 minutes Duration: approx. 15 minutes Marlboro premiere Last Marlboro performance: 1997 Berg’s Sieben frühe Liede, literally “seven early songs,” As she has done in other works such as her piano were written while he was still a student of Arnold concerto for Jonathan Biss, which was inspired by Schoenberg. In fact, three of these songs were premiered Beethoven’s third piano concerto, Shaw looks into music in a concert by Schoenberg’s students in late 1907, history to compose music for the present. This piece in around the time that Berg met the woman whom he particular eschews fixed meter to recall the conventions would marry. In honor of the 10-year anniversary of this of early music and to highlight the natural rhythms of the meeting, he later revisited and corrected a final version of libretto. The text of this short but wonderfully involved the songs. The whole set was not published until 1928, song is taken from a poem by Francesca Turini Bufalini when Berg arranged an orchestrated version. Each song (1553-1641). Not only does the language harken back to features text by a different poet, so there is no through- an artistic period before our own, but the music flits narrative, however the songs all feature similar themes, through references of erstwhile luminaries such as revolving around night, longing, and infatuation. -

01-Sargeant-PM

CERI OWEN Vaughan Williams’s Early Songs On Singing and Listening in Vaughan Williams’s Early Songs CERI OWEN I begin with a question not posed amid the singer narrates with ardent urgency their sound- recent and unusually liberal scholarly atten- ing and, apparently, their hearing. But precisely tion devoted to a song cycle by Ralph Vaughan who is engaged in these acts at this, the musi- Williams, the Robert Louis Stevenson settings, cal and emotional heart of the cycle? Songs of Travel, composed between 1901 and The recollected songs are first heard on the 1904.1 My question relates to “Youth and Love,” lips of the speaker in “The Vagabond,” an os- the fourth song of the cycle, in which an unex- tensibly archetypal Romantic wayfarer who in- pectedly impassioned climax erupts with pecu- troduces himself at the cycle’s opening in the liar force amid music of otherwise unparalleled lyric first-person, grimly issuing a characteris- serenity. Here, as strains of songs heard earlier tic demand for the solitary life on the open intrude into the piano’s accompaniment, the road. This lyric voice, its eye fixed squarely on the future, is retained in two subsequent songs, “Let Beauty Awake” and “The Roadside Fire” I thank Byron Adams, Daniel M. Grimley, and Julian (in which life with a beloved is contemplated).2 Johnson for their comments on this research, and espe- cially Benedict Taylor, for his invaluable editorial sugges- With “Youth and Love,” however, Vaughan tions. Thanks also to Clive Wilmer for his discussion of Williams rearranges the order of Stevenson’s Rossetti with me. -

Edexcel Aos1: Vaughan Williams's on Wenlock Edge

KSKS55 Edexcel AoS1: Vaughan Williams’s On Wenlock Edge Hanh Doan is a by Hanh Doan former AST and head of music, and currently works as a part-time music teacher at Beaumont School in St Albans. OVERVIEW She is the author of various books, On Wenlock Edge is a song cycle by Ralph Vaughan Williams that sets some of AE Housman’s poems from and writes articles his collection A Shropshire Lad. Published in 1896, the 63 poems in A Shropshire Lad reflect a variety of and resources for Music Teacher different themes (including the simple pleasures of rural life and a longing for lost innocence). They are written magazine, exam in different voices, including conversations from beyond the grave. As well as Vaughan Williams’s settings of boards and other six of these poems, other composers to set extracts from A Shropshire Lad include George Butterworth, Arthur music education publishers. Somervell and Ivor Gurney. Vaughan Williams set the following poems from the collection (the Roman numeral indicating the poem’s place in A Shropshire Lad): 1. XXXI ‘On Wenlock Edge’ 2. XXXII ‘From Far, from Eve and Morning’ 3. XXVII ‘Is My Team Ploughing’ 4. XVIII ‘Oh, When I Was in Love with You’ 5. XXI ‘Bredon Hill’ 6. L ‘Clun’ On Wenlock Edge is set for tenor and the unusual accompaniment of string quartet and piano. (Vaughan Williams also provided an alternative solo piano accompaniment.) Edexcel has chosen numbers 1, 3 and 5 for study at A level, but it is of course essential that students get to know the whole work. -

Brahms, Johannes (B Hamburg, 7 May 1833; D Vienna, 3 April 1897)

Brahms, Johannes (b Hamburg, 7 May 1833; d Vienna, 3 April 1897). German composer. The successor to Beethoven and Schubert in the larger forms of chamber and orchestral music, to Schubert and Schumann in the miniature forms of piano pieces and songs, and to the Renaissance and Baroque polyphonists in choral music, Brahms creatively synthesized the practices of three centuries with folk and dance idioms and with the language of mid and late 19thcentury art music. His works of controlled passion, deemed reactionary and epigonal by some, progressive by others, became well accepted in his lifetime. 1. Formative years. 2. New paths. 3. First maturity. 4. At the summit. 5. Final years and legacy. 6. Influence and reception. 7. Piano and organ music. 8. Chamber music. 9. Orchestral works and concertos. 10. Choral works. 11. Lieder and solo vocal ensembles. WORKS BIBLIOGRAPHY GEORGE S. BOZARTH (1–5, 10–11, worklist, bibliography), WALTER FRISCH (6– 9, 10, worklist, bibliography) Brahms, Johannes 1. Formative years. Brahms was the second child and first son of Johanna Henrika Christiane Nissen (1789–1865) and Johann Jakob Brahms (1806–72). His mother, an intelligent and thrifty woman simply educated, was a skilled seamstress descended from a respectable bourgeois family. His father came from yeoman and artisan stock that originated in lower Saxony and resided in Holstein from the mid18th century. A resourceful musician of modest talent, Johann Jakob learnt to play several instruments, including the flute, horn, violin and double bass, and in 1826 moved to the free Hanseatic port of Hamburg, where he earned his living playing in dance halls and taverns. -

A Dichterliebe by Robert Schumann

,A DICHTERLIEBE BY ROBERT SCHUMANN THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Hubert Neil Davidson, B. M. Denton, Texas August, 1957 PREFACE The purpose of this work, an analysis of the song cycle Dichterliebe (Op. 1+8) by Robert Schumann, is to recognize the special features of the songs which will contribute to their understanding and musical interpretation and perform- ance. The Dichterliebe was chosen as the composition to be analyzed because of its prominent position in the vocal lit.- erature of the Romantic period. An acquaintance with the life of the poet, Heinrich Heine, as well as the life of the composer of these songs and their relationship to each other contributes toward an understanding of the cycle. Each of the sixteen songs in the cycle is analyzed according to its most important characteristics, including text setting, general harmonic structure, important role of the accompaniment, expressive techniques, mood, tempo, rhythm, and dynamics. It is not the aim of this work to offer an extensive formal or harmonic analysis of this song cycle. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE . iii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.... ..... .v Chapter I. BACKGROUND OF THE DICHTERLIEBE . .1 Biographical Sketch of Robert Schumann The Life and Work of Heinrich Heine Robert Schumann's Relationship with Heinrich Heine History of Song Cycles up to and Past the Dichterliebe II. ANALYSIS OF THE DICHTERLIEBE . 18 I Im wundersch8ne Monat Mai II lus meinen Thranen spriessen III Die Rose, die Lilie, die Taube IV Wenn ich in!~deine Augen~seh1' V IhwiT miieine Seele tauchen VI Im Rhein, im heiligen Strome VII Ich rolle nicht VIII Und, ssten's die Blumen, die kleinen IX Das ist ein Fl8ten und Geigen x 'Tich das Liedchen~klingen XI Emn J17ling liebt ein Mdchen XII Am leuchtenden Sommemorgen XIII Ich hablimTTraum geweinet XIV llnHEhtlich im Traume seh' ich dich XV Aus alten Murchen Winkt es XVI Die alten b6sen Leider BIBLIOGRAPHY 0. -

Armida Abducts the Sleeping Rinaldo”

“Armida abducts the sleeping Rinaldo” Neutron autoradiography is capable of revealing different paint layers piled-up during the creation of the painting, whereas different pigments can be represented on separate films due to a contrast variation created by the differences in the half-life times of the isotopes. Thus, in many cases the individual brushstroke applied by the artist is made visible, as well as changes made during the painting process, so-called pentimentis. When investigating paintings that have been reliably authenticated, it is possible to identify the particular style of an artist. By an example - a painting from the French painter Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665), belonging to the Berlin Picture Gallery - the efficiency of neutron autoradiography is demonstrated as a non- destructive method. Fig. 1: Nicolas Poussin, Replica, “Armida abducts the sleeping Rinaldo”, (c. 1637), Picture Gallery Berlin, 120 x 150 cm2, Cat No. 486 The painting show scenes from the bible and from classical antiquity. In 1625 the legend of the sorceress Armida and the crusader Rinaldo had inspired Poussin to a painting named “Armida and Rinaldo”, now owned by the Dulwich Picture Gallery in London, that has been identified as an original. In contrast, the painting from the Berlin Picture Gallery “Armida abducts the sleeping Rinaldo” (Fig. 1) shows a different but similar scene, and was listed in the Berlin Gallery’s catalogue as a copy. To clarify the open question of the ascription a neutron radiography investigation was carried out. In Fig. 2, one of the autoradiographs is depicted. Fig. 2: Nicolas Poussin, “Armida abducts the sleeping Rinaldo”, 1st neutron autoradiography assembled from 12 image plate records: in order to investigate the whole picture, two separated irradiations were carried out and finally recomposed. -

3982.Pdf (118.1Kb)

II 3/k·YC)) b,~ 1'1 ,~.>u The next work in Brahms oeuvre, and our symphonic second move . PROGRAM ment, is his achingly beautiful Op. 82, Niinie, or "Lament." Again the Ci) I~ /6':; / duality of Brahms vision is evident in the structure of the setting of Schiller's poem. Brahms begins and ends the work in a delicate 6/4 v time, separated by a central majestic Andante in common time. Brahms lD~B~=':~i.~.~~ f~.:..::.?.................... GIU~3-':;') and Schiller describe not only the distance between humanity trapped in ............. our earthly condition and the ideal life of the gods, but also the lament "" that pain also invades the heavens. Not only are we separated from our bliss, but the gods must also endure pain as death separated Venus from Adonis, Orpheus from Euridice, and others. Some consider this music PAUSE among Brahms' most beautiful. r;J ~ ~\.e;Vll> I Boe (5 Traditionally a symphonic third movement is a minuet and trio or a scherzo. For tonight's "choral symphony" the Schicksalslied, or "Song of A "Choral Symphony" -Tragedy to Triumph Fate," fills that role. Continuing the two-fold vision of heaven and earth, Brahms' Op. 54 is set as an other-worldly adagio followed by a fiery ~ TRAGIC OVERTURE Op. 81 .......... L~:.s..:>.................JOHANNES BRAHMS allegro in 3/4 time, thus fulfilling our need for a two-part minuet and trio (1833-1897) movement. A setting of a HOideriein poem, the text again describes the idyllic life of the god's contrasted against the fearful fate of our life on NANIE Op. -

Dissertation Body

Summary of Three Dissertation Recitals by Leo R. Singer A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Music Performance) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Richard Aaron, Chair Professor Colleen Conway Assistant Professor Joseph Gascho Professor Andrew Jennings Professor James Joyce Leo R. Singer [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-2741-1104 © Leo R. Singer 2020 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation was made possible by the incredible faculty at the University of Michigan. Each course presented new information and ways of thinking, which in turn inspired the programming and performing choices for these three dissertation recitals. I would like to thank all the collaborators who worked tirelessly to make these performances special. I also must express my sincere and utmost gratitude to Professor Richard Aaron for his years of guidance, mentorship and inspiration. Lastly, I would like to thank my parents, Scott and Rochelle, my sister, Julie, the rest of my family, and all of my friends for their unwavering support throughout the many ups and downs during my years of education. !ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii ABSTRACT iv RECITALS I. MUSIC FROM FRANCE 1 RECITAL 1 PROGRAM 1 RECITAL 1 PROGRAM NOTES 2 BIBLIOGRAPHY 8 II. MUSIC FROM GERMANY AND AUSTRIA 10 RECITAL 2 PROGRAM 10 RECITAL 2 PROGRAM NOTES 12 BIBLIOGRAPHY 26 III. MUSIC FROM AMERICA 28 RECITAL 3 PROGRAM 28 RECITAL 3 PROGRAM NOTES 29 BIBLIOGRAPHY 37 !iii ABSTRACT In each of the three dissertation cello recitals, music from a different nation is featured. The first is music from France, the second from Germany and Austria, and the third from America. -

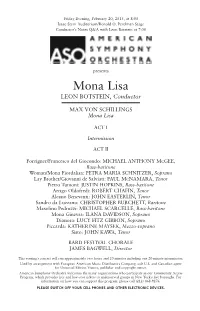

Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Friday Evening, February 20, 2015, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium/Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor MAX VON SCHILLINGS Mona Lisa ACT I Intermission ACT II Foreigner/Francesco del Giocondo: MICHAEL ANTHONY MCGEE, Bass-baritone Woman/Mona Fiordalisa: PETRA MARIA SCHNITZER, Soprano Lay Brother/Giovanni de Salviati: PAUL MCNAMARA, Tenor Pietro Tumoni: JUSTIN HOPKINS, Bass-baritone Arrigo Oldofredi: ROBERT CHAFIN, Tenor Alessio Beneventi: JOHN EASTERLIN, Tenor Sandro da Luzzano: CHRISTOPHER BURCHETT, Baritone Masolino Pedruzzi: MICHAEL SCARCELLE, Bass-baritone Mona Ginevra: ILANA DAVIDSON, Soprano Dianora: LUCY FITZ GIBBON, Soprano Piccarda: KATHERINE MAYSEK, Mezzo-soprano Sisto: JOHN KAWA, Tenor BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director This evening’s concert will run approximately two hours and 20 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. Used by arrangement with European American Music Distributors Company, sole U.S. and Canadian agent for Universal Edition Vienna, publisher and copyright owner. American Symphony Orchestra welcomes the many organizations who participate in our Community Access Program, which provides free and low-cost tickets to underserved groups in New York’s five boroughs. For information on how you can support this program, please call (212) 868-9276. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. FROM THE Music Director The Stolen Smile DVDs or pirated videos. Opera is the by Leon Botstein one medium from the past that resists technological reproduction. A concert This concert performance of Max von version still represents properly the Schillings’ 1915 Mona Lisa is the latest sonority and the multi-dimensional installment of a series of concert perfor- aspect crucial to the operatic experi- mances of rare operas the ASO has pio- ence. -

The Inventory of the Erica Morini Collection #1077

The Inventory of the Erica Morini Collection #1077 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Morini, Erica , 1904-1995. #1077 Preliminary Listing 2/27/91 Box( I. ORAL HISTORY A. AUSTRIAN PROJECT: THE REMINISCENCES OF ERICA MORINI. Oral History Research Office, Columbia University, 1981. 16 boxes: FULLER Morini, Erica #1077 Preliminary Listing 5/6/97 Box 1 I. Framed photographs, mostly family and friends, including some musicians (autographed): A. Bruno Walter B. Pablo Casals C. Bronislaw Huberman D. Otakar Sevcik E. Arturo Toscanini F. Wilhelm Furtwanger G. George Szell H. Stravinsky (in HBG's office) II. Certificate of appreciation, city of New York Ill. Award from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences, Nomination for Best Classical Performance, Chamber Music, 1961 Box2 I. Photographs II. Slide view finder Box3 I. Printed matter A. Programs, flyers, ads, featuring EM performances B. Menus from restaurants and dinner parties C. Catalogues from record stores D. "Bronislaw Huberman and the Unity of Europe," by Helmut Goetz, 1967 E. "Erika Morini erzahlt ausihrem leben," Die Frau, Oct. 1954 F. "Rostopovich, Off and Running-'Tritico,'" Saturday Review, March 11, 1967 G. "Basic Elements of Music" Paul Emerich H. EM on cover of AHET, 1957 I. Performing Arts, Jan. 1970 J. East ofFifth, Sept. 1956 K. "100 Years of Great Performances at Univ. of Michigan, 1879-1979 ," commemorative book L. Etude, Nov. 1954 M. Texas String News, Summer 1951 Box 3 N. The Strad, Dec. 1987 Box4 I. Correspondence, mainly from 1970's Including 1 Xmas card from Arturo Toscanini, 1943 II. Expenses/Financial Papers Ill. Newspaper clippings IV. -

Brahms's Song Collections," in Brahms Studies: Analytical and Historical Perspectives, Ed

Brahms’s Song Collections: Rethinking a Genre by Daniel Brian Stevens A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music Theory) in The University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Professor Kevin E. Korsyn, Chair Professor Walter T. Everett Associate Professor Johanna H. Prins Associate Professor Ramon Satyendra © Daniel Brian Stevens 2008 To Elizabeth and Olivia ii Acknowledgements This dissertation would not have been possible were it not for the generous support of many individuals. First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Kevin Korsyn, whose keen insights and sensitive guidance fueled this project from its conception to its completion. I am grateful for the imaginative ideas that he freely shared with me throughout this process, ideas that were deeply formative both of this dissertation and of its author. It has been an inspiration to study with this consummate music scholar throughout my years at the University of Michigan. I owe an enormous debt of gratitude to the other members of my committee, each of whom responded to this project with enthusiasm and support. Five years ago, Walter Everett first drew me to the interpretive challenges and delights of studying song, and his valuable research in the area of text-music relations made an important contribution to my thinking. His close reading of and detailed responses to many of the ideas in this dissertation have yielded many suggestions for future research that will keep me busy for at least another five years. I have also benefited greatly from Ramon Satyendra’s refined musical and philosophical mind; his encouragement of my work and the unique perspective he brought to it enriched this project in innumerable ways.