Alban Berg – Sieben Frühe Lieder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

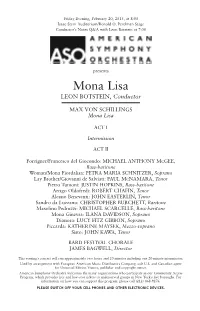

Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Friday Evening, February 20, 2015, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium/Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor MAX VON SCHILLINGS Mona Lisa ACT I Intermission ACT II Foreigner/Francesco del Giocondo: MICHAEL ANTHONY MCGEE, Bass-baritone Woman/Mona Fiordalisa: PETRA MARIA SCHNITZER, Soprano Lay Brother/Giovanni de Salviati: PAUL MCNAMARA, Tenor Pietro Tumoni: JUSTIN HOPKINS, Bass-baritone Arrigo Oldofredi: ROBERT CHAFIN, Tenor Alessio Beneventi: JOHN EASTERLIN, Tenor Sandro da Luzzano: CHRISTOPHER BURCHETT, Baritone Masolino Pedruzzi: MICHAEL SCARCELLE, Bass-baritone Mona Ginevra: ILANA DAVIDSON, Soprano Dianora: LUCY FITZ GIBBON, Soprano Piccarda: KATHERINE MAYSEK, Mezzo-soprano Sisto: JOHN KAWA, Tenor BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director This evening’s concert will run approximately two hours and 20 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. Used by arrangement with European American Music Distributors Company, sole U.S. and Canadian agent for Universal Edition Vienna, publisher and copyright owner. American Symphony Orchestra welcomes the many organizations who participate in our Community Access Program, which provides free and low-cost tickets to underserved groups in New York’s five boroughs. For information on how you can support this program, please call (212) 868-9276. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. FROM THE Music Director The Stolen Smile DVDs or pirated videos. Opera is the by Leon Botstein one medium from the past that resists technological reproduction. A concert This concert performance of Max von version still represents properly the Schillings’ 1915 Mona Lisa is the latest sonority and the multi-dimensional installment of a series of concert perfor- aspect crucial to the operatic experi- mances of rare operas the ASO has pio- ence. -

21St Century Consort Composer Performance List

21st Century Consort Composer List 1975 - 2019 Archive of performance recordings Hans Abrahamsen Winternacht (1976-78) 1986-12-06 (15:27) flute, clarinet, trumpet, French horn, piano, violin, cello, conductor John Adams Hallelujah Junction 2016-02-06 (17:25) piano, piano Road Movies 2012-05-05 (15:59) violin, piano Shaker Loops (1978) 2000-04-15 (26:34) violin, violin, violin, viola, cello, cello, contrabass, conductor Bruce Adolphe Machaut is My Beginning (1989) 1996-03-16 (5:01) violin, cello, flute, clarinet, piano Miguel Del Agui Clocks 2011-11-05 (20:46) violin, piano, viola, violin, cello Stephen Albert Treestone (1984) 1991-11-02 (38:15) soprano, tenor, violin, violin, viola, cello, bass, trumpet, clarinet, French horn, flute, percussion, piano, conductor Distant Hills Coming Nigh (1989-90) 1991-05-11 (31:28) tenor, soprano, violin, cello, bassoon, clarinet, viola, piano, French horn, double bass, flute, conductor Tribute (1988) 2002-01-26 (9:55) violin, piano Into Eclipse [New Version for Cello Solo Prepared by Jonathan Leshnoff] (2002) 2002-01-26 (31:53) violin, violin, viola, cello, cello, contrabass, flute, clarinet, trumpet, percussion, percussion, piano, conductor To Wake the Dead (1978) 1993-02-13 (27:24) soprano, violin, conductor Treestone (1978) 1984-03-17 (30:22) soprano, tenor, flute, clarinet, trumpet, horn, harp, violin, violin, viola, cello, bass, piano, percussion, conductor To Wake the Dead (1978) (Six Sentimental Songs and an Interlude After Finnegans Wake) 2013-02-23 (28:24) violin, clarinet, piano, flute, conductor, -

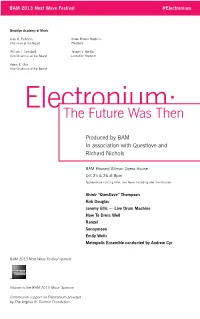

Electronium:The Future Was Then

BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival #Electronium Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Karen Brooks Hopkins, Chairman of the Board President William I. Campbell, Joseph V. Melillo, Vice Chairman of the Board Executive Producer Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Electronium:The Future Was Then Produced by BAM In association with Questlove and Richard Nichols BAM Howard Gilman Opera House Oct 25 & 26 at 8pm Approximate running time: two hours including one intermission Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson Kirk Douglas Jeremy Ellis — Live Drum Machine How To Dress Well Rahzel Sonnymoon Emily Wells Metropolis Ensemble conducted by Andrew Cyr BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival sponsor Viacom is the BAM 2013 Music Sponsor Commission support for Electronium provided by The Virginia B. Toulmin Foundation Electronium Metropolis Ensemble conducted by Andrew Cyr: Kristin Lee, violin (concertmaster) Francisco Fullana, violin Karen Kim, viola Hiro Matsuo, cello Mellissa Hughes, soprano Virginia Warnken, alto Geoffrey Silver, tenor Jonathan Woody, bass-baritone ADDITIONAL PRODUCTION CREDITS Arrangements by Daniel Felsenfeld, DD Jackson, Patrick McMinn and Anthony Tid Lighting design by Albin Sardzinski Sound engineering by John Smeltz Stage design by Alex Delaunay Stage manager Cheng-Yu Wei Electronium references the first electronic synthesizer created exclusively for the composition and performance of music. Initially created for Motown by composer-technologist Raymond Scott, the electronium was designed but never released for distribution; the one remaining machine is undergoing restoration. Complemented by interactive lighting and aural mash-ups, the music of Electronium: The Future Was Then honors the legacy of the electronium in a production that celebrates both digital and live music interplay. -

Songs of Love August 2

Concert Program IV: Songs of Love August 2 Tuesday, August 2 FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797–1828) 8:00 p.m., The Center for Performing Arts at Menlo-Atherton Selected Lieder S “Liebesbotschaft” P ROGRAM OVERVIEW “Nachtstück” “Auflösung” AM One of Brahms’s essential creative outlets was the vocal Paul Appleby, tenor; Wu Han, piano tradition he inherited from Franz Schubert. Brahms pos- sessed an innate sensitivity to the sympathy between poetry JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833–1897) and music—a vital concern of the Romantic generation. The Zwei Gesänge, op. 91 (1884; 1863–1864) perennially beloved Liebeslieder Waltzes contain all of “Gestillte Sehnsucht: In gold’nen Abendschein getauchet” the hallmarks of Brahms’s vocal oeuvre: warmth, intimacy, “Geistliches Wiegenlied: Die ihr schwebet” expressive nuance, and beguiling lyricism; the unique scor- Sasha Cooke, mezzo-soprano; Gilbert Kalish, piano; Paul Neubauer, viola ing of the Opus 91 Songs for Mezzo-Soprano, Viola, and ROBERT SCHUMANN (1810–1856) Piano adds to these qualities an exquisite melancholy. Con- ERT PROGR ERT Selected Lieder cert Program IV surrounds these works with the music of “Lehn’ deine Wang’ an meine Wang’,” op. 142, no. 2 C Schubert and Schumann (including the Spanische Liebes- “Du bist wie eine Blume,” op. 25, no. 24 lieder, which served as a model for Brahms’s Liebeslieder “Heiß mich nicht reden,” op. 98a, no. 5 Waltzes). Brahms’s legacy is evident in the hyper-Romantic Kelly Markgraf, baritone; Wu Han, piano ON Seven Early Songs of Alban Berg, one of Brahms’s early- C twentieth-century artistic heirs. ROBERT SCHUMANN Spanische Liebeslieder, op. 138 (1849) Erin Morley, soprano; Sasha Cooke, mezzo-soprano; Paul Appleby, tenor; Kelly Markgraf, baritone; Gilbert Kalish, Wu Han, piano I NTERMISSION SPECIAL THANKS AlbaN BERG (1885–1935) Music@Menlo dedicates this performance to Linda DeMelis Sieben frühe Lieder (1905–1908) and Ted Wobber with gratitude for their generous support. -

Bridging the Gap Between Opera and Musical Theatre

The Crossover Opera Singer: Bridging the Gap Between Opera and Musical Theatre D.M.A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Keyona Willis-Lynam, M.M Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2015 D.M.A. Document Committee: J. Robin Rice, Advisor Joe Duchi Kristine Kearney Copyright by Keyona Willis-Lynam 2015 Abstract For decades, a divide has existed between opera and musical theatre, with the lesser value being placed upon the latter. Singers, from the start of their training, are told to choose a genre if one wants to achieve any type of singing success. This type of division creates a chasm of isolation and misunderstanding between the musical styles. From academia, to the stage, to the concert goer, one’s allegiance to opera versus musical theatre has been built upon a firm foundation of contrast, without acknowledging that both genres have ties to one another. As a result, most teaching of singing is done from the perspective of the classical singing style, with little to no mention of how to efficiently and healthily sing in a musical theatre style. In today’s social and economic climate, opera houses across the United States and abroad are seeing a decline in ticket sales; some have been able to restructure to survive, while others are shutting down. Companies are seeking a variety of ways to stay connected to the community; one avenue that has produced an area of contention is the addition of musical theatre productions to the season’s billing. -

A Singing Voice Dataset

VOCALSET: A SINGING VOICE DATASET Julia Wilkins1;2 Prem Seetharaman1 Alison Wahl2;3 Bryan Pardo1 1 Computer Science, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 2 School of Music, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 3 School of Music, Ithaca College, Ithaca, NY [email protected] ABSTRACT Gender and Voice Type Distribution We present VocalSet, a singing voice dataset of a capella 11 10 Voice Type singing. Existing singing voice datasets either do not 9 Baritone capture a large range of vocal techniques, have very few 8 Bass singers, or are single-pitch and devoid of musical context. 7 VocalSet captures not only a range of vowels, but also a 6 Bass−Baritone 5 Countertenor diverse set of voices on many different vocal techniques, Count sung in contexts of scales, arpeggios, long tones, and ex- 4 Mezzo−Soprano 3 cerpts. VocalSet has recordings of 10.1 hours of 20 pro- Soprano 2 fessional singers (11 male, 9 female) performing 17 differ- 1 Tenor ent different vocal techniques. This data will facilitate the 0 development of new machine learning models for singer F M identification, vocal technique identification, singing gen- Gender eration and other related applications. To illustrate this, we establish baseline results on vocal technique classification Figure 1. Distribution of singer gender and voice type. and singer identification by training convolutional network VocalSet data comes from 20 professional male and female classifiers on VocalSet to perform these tasks. singers ranging in voice type. 1. INTRODUCTION plored [2,5]. VocalSet can be used in a similar way, but for VocalSet is a singing voice dataset containing 10.1 hours singing voice generation. -

CONTACT: Robert Patterson for Music at St. Alban's 718 984 7756 for IMMEDIATE RELEASE METROPOLITAN OPERA SOPRANO TONNA MILLER

CONTACT: Robert Patterson for Music at St. Alban’s 718 984 7756 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE METROPOLITAN OPERA SOPRANO TONNA MILLER AND INTERNATIONAL CLARINET VIRTUOSO IGOR BEGELMAN TO PERFORM “MUSIC OF TRIUMPH AND JUBILATION” IN SAINT ALBAN’S CONCERT SERIES WITH THE SAINT ALBAN'S FESTIVAL CHORAL SOCIETY, SINFONIA CELESTIS AND OTHER SOLOISTS ON SATURDAY, APRIL 26, 2008 AND SUNDAY, APRIL 27, 2008 Staten Island, NY – April 01, 2008– Music at Saint Alban’s announced today that the Saint Alban's Festival Choral Society, Sinfonia Celestis and soloists, conducted by Artistic Director and Series Founder Jeffrey Hoffman, will perform “Music of Triumph and Jubilation” – a concert of masterworks for chorus, soloists and chamber orchestra – on Saturday, April 26, 2008 at 7:30 PM and Sunday, April 27, 2008 at 3:30 PM. Featured soloists for this concert are virtuoso clarinetist Igor Begelman, and Metropolitan Opera soprano Tonna Miller. They will be joined as soloists by soprano Laurelyn Watson Chase, mezzo-soprano Tracy Bidleman, tenor Robert Cunningham, and bass-baritone Simon Cram. The concert will take place in the parish church of Saint Alban’s Episcopal Church, 76 Saint Alban’s Place, Eltingville, Staten Island 10312. The music performed on this concert will include Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Concerto for Clarinet and Orchestra, his motet for solo soprano Exsultate jubilate, and Franz Joseph Haydn’s Missa in Angustiis (“Lord Nelson” Mass). Tickets for this concert are priced at $20 for adults and $15 for senior citizens and students, and may be purchased by calling 718-984-7756 or by visiting www.MusicatSaintAlbans.org. -

Historical Tradition in the Pre-Serial Atonal Music of Alban Berg. William Glenn Walden Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1988 Historical Tradition in the Pre-Serial Atonal Music of Alban Berg. William Glenn Walden Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Walden, William Glenn, "Historical Tradition in the Pre-Serial Atonal Music of Alban Berg." (1988). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4547. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4547 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. -

San Francisco Symphony 2021–22 Season Concert Calendar

San Francisco Symphony 2021-22 Season Calendar Contact: Public Relations San Francisco Symphony (415) 503-5474 [email protected] www.sfsymphony.org/press SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY 2021–22 SEASON CONCERT CALENDAR PLEASE NOTE: Single tickets for the San Francisco Symphony’s 2021–22 concerts go on sale TUESDAY, August 31 at 10am and can be purchased online at www.sfsymphony.org or by phone at (415) 864-6000. All concerts are at Davies Symphony Hall, 201 Van Ness Avenue, San Francisco, unless otherwise noted. FILM SERIES The Princess Bride—Film with Live Orchestra Wednesday, September 22, 2021 at 7:30pm Thursday, September 23, 2021 at 7:30pm Sarah Hicks conductor San Francisco Symphony MARK KNOPFLER The Princess Bride ROB REINER director FILM SERIES Apollo 13—Film with Live Orchestra Friday, September 24, 2021 at 7:30pm Saturday, September 25, 2021 at 7:30pm Constantine Kitsopoulos conductor San Francisco Symphony JAMES HORNER Apollo 13 RON HOWARD director SPECIAL EVENT All San Francisco Concert Thursday, September 30, 2021 at 7:30pm Esa-Pekka Salonen conductor Esperanza Spalding vocalist and bass Alonzo King LINES Ballet San Francisco Symphony JOHN ADAMS Slonimsky’s Earbox ALBERTO GINASTERA Estancia Suite WAYNE SHORTER Selected Songs SILVESTRE REVUELTAS Noche de encantamiento, from La noche de los Mayas SPECIAL EVENT San Francisco Symphony Re-Opening Night Friday, October 1, 2021 at 7pm Esa-Pekka Salonen conductor Esperanza Spalding vocalist and bass Alonzo King LINES Ballet San Francisco Symphony JOHN ADAMS Slonimsky’s Earbox -

Alban Berg's Sieben Frühe Lieder

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 6-16-2014 Alban Berg’s Sieben frühe Lieder: An Analysis of Musical Structures and Selected Performances Lisa A. Lynch University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Lynch, Lisa A., "Alban Berg’s Sieben frühe Lieder: An Analysis of Musical Structures and Selected Performances" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 480. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/480 Alban Berg’s Sieben frühe Lieder: An Analysis of Musical Structures and Selected Performances Lisa Anne Lynch, DMA University of Connecticut, 2014 ABSTRACT Alban Berg’s Sieben frühe Lieder, composed between 1905-08, lie on the border between late 19th-century Romanticism and early atonality, resulting in their particularly lyrical and yet distinctly modern character. This dissertation looks in detail at the songs with an emphasis on the relevance of a musical analysis to performers. Part I provides an overview of the historical context surrounding the Sieben frühe Lieder, including Berg’s studies with Schoenberg, stylistic features, biographical details, and analytic approaches to Berg’s work. The primary focus of the dissertation, Part II, is a study of each individual song. Each analysis begins with an overview of the formal design of the piece, taking into consideration the structure and content of the poetry, and includes a chart of the song’s form. A detailed study of the harmonic structure and motivic development within the song follows. The analysis also addresses the nuances of text setting. Following each analysis of musical structure, specific aspects of performance are discussed, including comparisons of recordings and the expressive effects of different performers’ choices. -

01-14-2020 Traviata Eve.Indd

GIUSEPPE VERDI la traviata conductor Opera in three acts Karel Mark Chichon Libretto by Francesco Maria Piave, production Michael Mayer based on the play La Dame aux Camélias by Alexandre Dumas fils set designer Christine Jones Tuesday, January 14, 2020 costume designer 7:30–10:40 PM Susan Hilferty lighting designer Kevin Adams choreographer Lorin Latarro The production of La Traviata was revival stage director Sarah Ina Meyers made possible by a generous gift from The Paiko Foundation Major additional funding for this production was received from Mercedes T. Bass, Mr. and Mrs. Paul M. Montrone, and Rolex general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2019–20 SEASON The 1,028th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S la traviata conductor Karel Mark Chichon in order of vocal appearance violet ta valéry annina Aleksandra Kurzak Maria Zifchak flor a bervoix giuseppe Megan Marino Patrick Miller the marquis d’obigny giorgio germont Christopher Job Quinn Kelsey baron douphol a messenger Trevor Scheunemann Ross Benoliel dr. grenvil Paul Corona germont’s daughter Kendall Cafaro gastone solo dancers Tonight’s Brian Michael Moore** Garen Scribner performances of Sara Mearns the roles of Violetta and Alfredo are alfredo germont underwritten by the Dmytro Popov Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Great Singers Fund. Tuesday, January 14, 2020, 7:30–10:40PM MARTY SOHL / MET OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Verdi’s La Traviata Musical Preparation Linda Hall, Derrick Inouye, Bradley Moore*, -

ALSO on Signumclassics

115booklet 30/11/07 10:01 Page 1 ALSO on signumclassics The Hymns Album Sir Michael Tippett: Choral Images Man I Sing Huddersfield Choral Society / Joseph Cullen The BBC Singers / Stephen Cleobury Choral Music by Bob Chilcott SIGCD079 SIGCD092 The BBC Singers / Bob Chilcott SIGCD100 Choral Arrangements by Clytus Gottwald Monteverdi Vespers of 1610 The Rodolfus Choir / Ralph Allwood The Rodolfus Choir & Southern Sinfonia / SIGCD102 Ralph Allwood SIGCD109 Available through most record stores and at www.signumrecords.com For more information call +44 (0) 20 8997 4000 115booklet 30/11/07 10:02 Page 3 HEAR my words Hear my words 1. Hear my words, ye people Hubert Parry [15.03] This disc, featuring some of the best-loved After the justified success of Blest Pair of Sirens in 2. Teach me, O Lord William Byrd [3.23] anthems in the church repertoire, is loosely woven 1887, Parry could reasonably be regarded as the 3. Magnificat in G Charles Villiers Stanford [3.57] around two strands in particular. The first is the leading choral composer in England. Hear my 4. Benedictus from Missa Brevis Sancti treble, or boy soprano, voice. The English choral words, ye people was written for the Diocesan Joannis de Deo Hob XXII/7 tradition, at least as old (for example) as the late Choral Festival in Salisbury Cathedral in 1894, in (Little Organ Mass) Joseph Haydn [4.24] mediaeval Eton Choirbook, depends integrally on which choirs were drawn together from across the 5. Thou, O God, art praised in Sion Malcolm Boyle [6.04] the nurturing of treble singing in schools.