Wozzeck by Alban Berg Correlations Between Text and Music in Opera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For All the Attention Paid to the Striking Passage of Thirty-Four

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Humanities Commons for Jane, on our thirty-fourth Accents of Remorse The good has never been perfect. There is always some flaw in it, some defect. First Sightings For all the attention paid to the “interview” scene in Benjamin Britten’s opera Billy Budd, its musical depths have proved remarkably resistant to analysis and have remained unplumbed. This striking passage of thirty-four whole-note chords has probably attracted more comment than any other in the opera since Andrew Porter first spotted shortly after the 1951 premiere that all the chords harmonize members of the F major triad, leading to much discussion over whether or not the passage is “in F major.” 1 Beyond Porter’s perception, the structure was far from obvious, perhaps in some way unprecedented, and has remained mysterious. Indeed, it is the undisputed gnomic power of its strangeness that attracted (and still attracts) most comment. Arnold Whittall has shown that no functional harmonic or contrapuntal explanation of the passage is satisfactory, and proceeded from there to make the interesting assertion that that was the point: The “creative indecision”2 that characterizes the music of the opera was meant to confront the listener with the same sort of difficulty as the layers of irony in Herman Melville’s “inside narrative,” on which the opera is based. To quote a single sentence of the original story that itself contains several layers of ironic ambiguity, a sentence thought by some—I believe mistakenly—to say that Vere felt no remorse: 1. -

Understanding Character Agency Through the Music of Wozzeck

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 4-2016 Oppression, Evaluation, and Direction: Understanding Character Agency through the Music of Wozzeck Eric Allen Hester Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Hester, Eric Allen, "Oppression, Evaluation, and Direction: Understanding Character Agency through the Music of Wozzeck" (2016). Master's Theses. 702. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/702 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OPPRESSION, EVALUATION, AND DIRECTION: UNDERSTANDING CHARACTER AGENCY THROUGH THE MUSIC OF WOZZECK by Eric Allen Hester A Thesis submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music School of Music Western Michigan University April 2016 Thesis Committee: Alexander M. Cannon, Ph.D., Chair Matthew C. Steel, Ph.D. Daniel C. Jacobson, Ph.D. Paul R. Solomon, M.F.A. OPPRESSION, EVALUATION, AND DIRECTION: UNDERSTANDING CHARACTER AGENCY THROUGH THE MUSIC OF WOZZECK Eric Allen Hester, M.A. Western Michigan University, 2016 In Alban Berg’s opera, Wozzeck, the concept of agency is one of fundamental importance. The oppressive dictates of fate and social position are featured prominently in the plot of the opera, and the characters evaluate their relationship with these oppressive structures in order to direct their agency. -

Alban Berg – Sieben Frühe Lieder

DOI: 10.2478/ajm-2020-0012 Studies Alban Berg – Sieben frühe Lieder. Performance perspectives IONELA BUTU, Associate Professor PhD “George Enescu” National University of Arts ROMANIA∗ Bergʼs worldwide reputation had been consolidated with orchestral and chamber works and the opera Wozzeck. (...) For different reasons, his dimension as a composer of songs does not seem to be very large, and yet it is fundamental to his personality nevertheless. Mark DeVoto Abstract: The study presents several interpretative suggestions made from the perspective of the accompanying pianist that played Alban Bergʼs Sieben frühe Lieder. Why this topic? Because in the Romanian music literature, there is nothing written about the song cycle Sieben frühe Lieder by Alban Berg, which is a representative work in the history of the art song. The theme, addressed in the literature written abroad, is treated mostly from a musicological standpoint. That is why we considered it useful to make some observations of an interpretative nature. They will become relevant if read in parallel with the PhD thesis entitled Alban Bergʼs “Sieben frühe Lieder”: An Analysis of Musical Structures and Selected Performances, written by Lisa A. Lynch (the only documentary source that proposes in-depth syntactic analyses of the work, associated with valuable interpretative suggestions made from a vocal perspective). We also considered useful, during the study, the comparison between the two variants of the work: the chamber/voice-piano version and the orchestral version. The analysis of the symphonic text was carried out intending the observation of significant details useful for realizing an expressive duo performance. Of course, our interpretative suggestions are a variant between many others. -

TURANDOT Cast Biographies

TURANDOT Cast Biographies Soprano Martina Serafin (Turandot) made her San Francisco Opera debut as the Marshallin in Der Rosenkavalier in 2007. Born in Vienna, she studied at the Vienna Conservatory and between 1995 and 2000 she was a member of the ensemble at Graz Opera. Guest appearances soon led her to the world´s premier opera stages, including at the Vienna State Opera where she has been a regular performer since 2005. Serafin´s repertoire includes the role of Lisa in Pique Dame, Sieglinde in Die Walküre, Elisabeth in Tannhäuser, the title role of Manon Lescaut, Lady Macbeth in Macbeth, Maddalena in Andrea Chénier, and Donna Elvira in Don Giovanni. Upcoming engagements include Elsa von Brabant in Lohengrin at the Opéra National de Paris and Abigaille in Nabucco at Milan’s Teatro alla Scala. Dramatic soprano Nina Stemme (Turandot) made her San Francisco Opera debut in 2004 as Senta in Der Fliegende Holländer, and has since returned to the Company in acclaimed performances as Brünnhilde in 2010’s Die Walküre and in 2011’s Ring cycle. Since her 1989 professional debut as Cherubino in Cortona, Italy, Stemme’s repertoire has included Rosalinde in Die Fledermaus, Mimi in La Bohème, Cio-Cio-San in Madama Butterfly, the title role of Manon Lescaut, Tatiana in Eugene Onegin, the title role of Suor Angelica, Euridice in Orfeo ed Euridice, Katerina in Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the Countess in Le Nozze di Figaro, Marguerite in Faust, Agathe in Der Freischütz, Marie in Wozzeck, the title role of Jenůfa, Eva in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Elsa in Lohengrin, Amelia in Un Ballo in Machera, Leonora in La Forza del Destino, and the title role of Aida. -

Franz A. Birgel Muhlenberg College

Werner Herzog's Debt to Georg Buchner Franz A. Birgel Muhlenberg College The filmmaker Wemcr Herzog has been labeled eve1)1hing from a romantic, visionary idealist and seeker of transcendence to a reactionary. regressive fatalist and t)Tannical megalomaniac. Regardless of where viewers may place him within these e:-..1reme positions of the spectrum, they will presumably all admit that Herzog personifies the true auteur, a director whose unmistakable style and wor1dvie\v are recognizable in every one of his films, not to mention his being a filmmaker whose art and projected self-image merge to become one and the same. He has often asserted that film is the art of i1literates and should not be a subject of scholarly analysis: "People should look straight at a film. That's the only \vay to see one. Film is not the art of scholars, but of illiterates. And film culture is not analvsis, it is agitation of the mind. Movies come from the count!)' fair and circus, not from art and academicism" (Greenberg 174). Herzog wants his ideal viewers to be both mesmerized by his visual images and seduced into seeing reality through his eyes. In spite of his reference to fairgrounds as the source of filmmaking and his repeated claims that his ·work has its source in images, it became immediately transparent already after the release of his first feature film that literature played an important role in the development of his films, a fact which he usually downplays or effaces. Given Herzog's fascination with the extremes and mysteries of the human condition as well as his penchant for depicting outsiders and eccentrics, it comes as no surprise that he found a kindred spirit in Georg Buchner whom he has called "probably the most ingenious writer for the stage that we ever had" (Walsh 11). -

The Application of Bel Canto Concepts and Principles to Trumpet Pedagogy and Performance

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1980 The Application of Bel Canto Concepts and Principles to Trumpet Pedagogy and Performance. Malcolm Eugene Beauchamp Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Beauchamp, Malcolm Eugene, "The Application of Bel Canto Concepts and Principles to Trumpet Pedagogy and Performance." (1980). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3474. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3474 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

William Kentridge Brings 'Wozzeck' Into the Trenches

William Kentridge Brings ‘Wozzeck’ Into the Trenches The artist’s production of Berg’s brutal opera, updated to World War I, has come to the Metropolitan Opera. By Jason Farago (December 26, 2019) ”Credit...Devin Yalkin for The New York Times Three years ago, on a trip to Johannesburg, I had the chance to watch the artist William Kentridge working on a new production of Alban Berg’s knifelike opera “Wozzeck.” With a troupe of South African performers, Mr. Kentridge blocked out scenes from this bleak tale of a soldier driven to madness and murder — whose setting he was updating to the years around World War I, when it was written, through the hand-drawn animations and low-tech costumes that Metropolitan Opera audiences have seen in his stagings of Berg’s “Lulu” and Shostakovich’s “The Nose.” Some of what I saw in Mr. Kentridge’s studio has survived in “Wozzeck,” which opens at the Met on Friday. But he often works on multiple projects at once, and much of the material instead ended up in “The Head and the Load,” a historical pageant about the impact of World War I in Africa, which New York audiences saw last year at the Park Avenue Armory. Mr. Kentridge’s “Wozzeck” premiered at the Salzburg Festival in 2017. Zachary Woolfe of The New York Times called it “his most elegant and powerful operatic treatment yet.” At the Met, the Swedish baritone Peter Mattei will sing the title role for the first time; Elza van den Heever, like Mr. Kentridge from Johannesburg, plays his common-law wife, Marie; and Yannick Nézet- Séguin, the company’s music director, will conduct. -

Così Fan Tutte Cast Biography

Così fan tutte Cast Biography (Cahir, Ireland) Jennifer Davis is an alumna of the Jette Parker Young Artist Programme and has appeared at the Royal Opera, Covent Garden as Adina in L’Elisir d’Amore; Erste Dame in Die Zauberflöte; Ifigenia in Oreste; Arbate in Mitridate, re di Ponto; and Ines in Il Trovatore, among other roles. Following her sensational 2018 role debut as Elsa von Brabant in a new production of Lohengrin conducted by Andris Nelsons at the Royal Opera House, Davis has been propelled to international attention, winning praise for her gleaming, silvery tone, and dramatic characterisation of remarkable immediacy. (Sacramento, California) American Mezzo-soprano Irene Roberts continues to enjoy international acclaim as a singer of exceptional versatility and vocal suppleness. Following her “stunning and dramatically compelling” (SF Classical Voice) performances as Carmen at the San Francisco Opera in June, Roberts begins the 2016/2017 season in San Francisco as Bao Chai in the world premiere of Bright Sheng’s Dream of the Red Chamber. Currently in her second season with the Deutsche Oper Berlin, her upcoming assignments include four role debuts, beginning in November with her debut as Urbain in David Alden’s new production of Les Huguenots led by Michele Mariotti. She performs in her first Ring cycle in 2017 singing Waltraute in Die Walküre and the Second Norn in Götterdämmerung under the baton of Music Director Donald Runnicles, who also conducts her role debut as Hänsel in Hänsel und Gretel. Additional roles for Roberts this season include Rosina in Il barbiere di Siviglia, Fenena in Nabucco, Siebel in Faust, and the title role of Carmen at Deutsche Oper Berlin. -

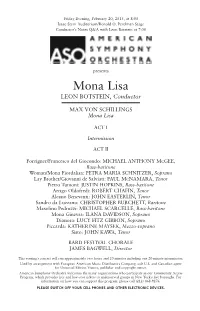

Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Friday Evening, February 20, 2015, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium/Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor MAX VON SCHILLINGS Mona Lisa ACT I Intermission ACT II Foreigner/Francesco del Giocondo: MICHAEL ANTHONY MCGEE, Bass-baritone Woman/Mona Fiordalisa: PETRA MARIA SCHNITZER, Soprano Lay Brother/Giovanni de Salviati: PAUL MCNAMARA, Tenor Pietro Tumoni: JUSTIN HOPKINS, Bass-baritone Arrigo Oldofredi: ROBERT CHAFIN, Tenor Alessio Beneventi: JOHN EASTERLIN, Tenor Sandro da Luzzano: CHRISTOPHER BURCHETT, Baritone Masolino Pedruzzi: MICHAEL SCARCELLE, Bass-baritone Mona Ginevra: ILANA DAVIDSON, Soprano Dianora: LUCY FITZ GIBBON, Soprano Piccarda: KATHERINE MAYSEK, Mezzo-soprano Sisto: JOHN KAWA, Tenor BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director This evening’s concert will run approximately two hours and 20 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. Used by arrangement with European American Music Distributors Company, sole U.S. and Canadian agent for Universal Edition Vienna, publisher and copyright owner. American Symphony Orchestra welcomes the many organizations who participate in our Community Access Program, which provides free and low-cost tickets to underserved groups in New York’s five boroughs. For information on how you can support this program, please call (212) 868-9276. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. FROM THE Music Director The Stolen Smile DVDs or pirated videos. Opera is the by Leon Botstein one medium from the past that resists technological reproduction. A concert This concert performance of Max von version still represents properly the Schillings’ 1915 Mona Lisa is the latest sonority and the multi-dimensional installment of a series of concert perfor- aspect crucial to the operatic experi- mances of rare operas the ASO has pio- ence. -

London's Symphony Orchestra

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Sunday 7 May 2017 7pm Barbican Hall SHOSTAKOVICH SYMPHONY NO 15 Mussorgsky arr Rimsky-Korsakov Prelude to ‘Khovanshchina’ Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto INTERVAL London’s Symphony Orchestra Shostakovich Symphony No 15 Sir Mark Elder conductor Anne-Sophie Mutter violin Concert finishes approx 9.10pm Generously supported by Celia & Edward Atkin CBE 2 Welcome 7 May 2017 Welcome Living Music Kathryn McDowell In Brief A warm welcome to this evening’s LSO concert at BMW LSO OPEN AIR CLASSICS 2017 the Barbican, where we are joined by Sir Mark Elder for an all-Russian programme of works by Mussorgsky, The London Symphony Orchestra, in partnership with Tchaikovsky and Shostakovich. BMW and conducted by Valery Gergiev, performs an all-Rachmaninov programme in London’s Trafalgar The concert opens with the prelude to Mussorgsky’s Square on Sunday 21 May, the sixth concert in the opera Khovanshchina, in an arrangement by fellow Orchestra’s annual BMW LSO Open Air Classics Russian composer, Rimsky-Korsakov. Then we are series, free and open to all. delighted to see Anne-Sophie Mutter return as the soloist in Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto, before lso.co.uk/openair Sir Mark Elder concludes the programme with Shostakovich’s final symphony, No 15. LSO WIND ENSEMBLE ON LSO LIVE I hope you enjoy the performance. I would like to take this opportunity to welcome Celia and The new recording of Mozart’s Serenade No 10 Edward Atkin, and to thank them for their generous for Wind Instruments (‘Gran Partita’) by the LSO support of this evening’s concert. -

A History of Modern Drama

Krasner_bindex.indd 404 8/11/2011 5:01:22 PM A History of Modern Drama Volume I Krasner_ffirs.indd i 8/12/2011 12:32:19 PM Books by David Krasner An Actor’s Craft: The Art and Technique of Acting (2011) Theatre in Theory: An Anthology (editor, 2008) American Drama, 1945–2000: An Introduction (2006) Staging Philosophy: New Approaches to Theater, Performance, and Philosophy (coeditor with David Saltz, 2006) A Companion to Twentieth-Century American Drama (editor, 2005) A Beautiful Pageant: African American Theatre, Drama, and Performance, 1910–1927 (2002), 2002 Finalist for the Theatre Library Association’s George Freedley Memorial Award African American Performance and Theater History: A Critical Reader (coeditor with Harry Elam, 2001), Recipient of the 2002 Errol Hill Award from the American Society for Theatre Research (ASTR) Method Acting Reconsidered: Theory, Practice, Future (editor, 2000) Resistance, Parody, and Double Consciousness in African American Theatre, 1895–1910 (1997), Recipient of the 1998 Errol Hill Award from ASTR See more descriptions at www.davidkrasner.com Krasner_ffirs.indd ii 8/12/2011 12:32:19 PM A History of Modern Drama Volume I David Krasner A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication Krasner_ffirs.indd iii 8/12/2011 12:32:19 PM This edition first published 2012 © 2012 David Krasner Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell. Registered Office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell. -

Woyzeck Bursts Onto the Ensemble Theatre Company Stage

MEDIA RELEASE CONTACT: Josh Gren [email protected] or 805.965.5400 x103 ELECTRIFYING TOM WAITS MUSICAL WOYZECK BURSTS ONTO THE ENSEMBLE THEATRE COMPANY STAGE March 25, 2015 – Santa Barbara, CA — The influential 19th Century play about a soldier fighting to retain his humanity has been transformed into a tender and carnivalesque musical by the legendary vocalist, Tom Waits. “If there’s one thing you can say about mankind,” the show begins, “there’s nothing kind about man.” The haunting opening phrase is the heart of the thrilling, bold, and contemporary English adaptation of Woyzeck – the classic German play, being presented at Ensemble Theatre Company this April. Inspired by the true story of a German soldier who was driven mad by army medical experiments and infidelity, Georg Büchner’s dynamic and influential 1837 poetic play was left unfinished after the untimely death of its author. In 2000, Waits and his wife and collaborator, Kathleen Brennan, resurrected the piece, wrote music for an avant-garde production in Denmark, and the resulting work became a Woyzeck musical and an album entitled “Blood Money.” “[The music] is flesh and bone, earthbound,” says Waits. “The songs are rooted in reality: jealousy, rage…I like a beautiful song that tells you terrible things. We all like bad news out of a pretty mouth.” Woyzeck runs at the New Vic Theater from April 16 – May 3 and opens Saturday, April 18. Jonathan Fox, who has served as ETC’s Executive Artistic Director since 2006, will direct the ambitious, wild, and long-awaited musical. “It’s one of the most unusual productions we’ve undertaken,” says Fox.