Drama Around a War-Time Heisenberg Letter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cincinnati

! "# $ % & % ' % !" #$ !% !' &$ &""! '() ' #$ *+ ' "# ' '% $$(' ,) * !$- .*./- 0 #!1- 2 *,*- Atomic Apocalypse – ‘Nuclear Fiction’ in German Literature and Culture A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) in the Department of German Studies of the College of Arts and Sciences 2010 by Wolfgang Lueckel B.A. (equivalent) in German Literature, Universität Mainz, 2003 M.A. in German Studies, University of Cincinnati, 2005 Committee Chair: Sara Friedrichsmeyer, Ph.D. Committee Members: Todd Herzog, Ph.D. (second reader) Katharina Gerstenberger, Ph.D. Richard E. Schade, Ph.D. ii Abstract In my dissertation “Atomic Apocalypse – ‘Nuclear Fiction’ in German Literature and Culture,” I investigate the portrayal of the nuclear age and its most dreaded fantasy, the nuclear apocalypse, in German fictionalizations and cultural writings. My selection contains texts of disparate natures and provenance: about fifty plays, novels, audio plays, treatises, narratives, films from 1946 to 2009. I regard these texts as a genre of their own and attempt a description of the various elements that tie them together. The fascination with the end of the world that high and popular culture have developed after 9/11 partially originated from the tradition of nuclear fiction since 1945. The Cold War has produced strong and lasting apocalyptic images in German culture that reject the traditional biblical apocalypse and that draw up a new worldview. In particular, German nuclear fiction sees the atomic apocalypse as another step towards the technical facilitation of genocide, preceded by the Jewish Holocaust with its gas chambers and ovens. -

GV-Vorlage Präsident

Eine Initiative von Wissenschaft, Politik und Wirtschaft Die Eröffnung des Harnack-Hauses am 7. Mai 1929 war für Berliner Wissenschaftler, Politiker und Spitzenvertreter der Wirtschaft ein großer Tag, hatten sie doch mit vereinten Kräften erreicht, dass Berlin endlich ein Vortrags- und Begegnungszentrum für die Mitglieder der berühmten Dahlemer Institute und gleichzeitig ein Gästehaus für Wissenschaftler aus aller Welt bekam. Initiatoren des Hauses waren vor allem Adolf von Harnack und Friedrich Glum, die energisch für die Realisierung des Projektes gekämpft hatten. Der Theologe Adolf von Harnack, erster Präsident der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft, Robert Andrews Millikan im Harnack-Haus © Bundesarchiv Bild 102-12631 / CC-BA-SA,/Fotograf: hatte vor allem ein Ziel: Die Isolation der deutschen Georg Pahl Wissenschaft nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg zu über- winden und durch internationale Zusammenarbeit Spitzenleistungen zu ermöglichen. Harnacks Bestrebungen, ein internationales Forscher- zentrum in Dahlem aufzubauen, wurden tatkräftig unterstützt von Generaldirektor Glum, der innerhalb der KWG, bei Firmen und Privatleuten für die Idee einer internationalen Begeg- nungsstätte Werbung gemacht hatte. Im Juni 1926 beschloss der Senat der Kaiser- Wilhelm-Gesellschaft die Gründung des Harnack- Hauses - auch mit dem Ziel, Dank abzustatten für die Gastfreundschaft, die deutsche Forscher im Ausland erfahren hatten. Als wichtigste politische Paten des Harnack-Hauses stellten sich Reichsau- ßenminister Gustav Stresemann, Reichskanzler Wilhelm Marx und der einflussreiche Zentrums- Abgeordnete Georg Schreiber heraus, die der Idee Harnacks die nötige politische Lobby verschafften und öffentliche Mittel für den Bau des Hauses durchsetzten. Konkret bedeutete das: Das Reich Einweihung des Kaiser-Wilhelm-Instituts in Berlin Dahlem, 28. Oktober 1913 zahlte 1,5 Millionen Reichsmark, während Preußen © Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R15350 / CC-BY-SA das Grundstück zur Verfügung stellte. -

The Historic Dahlem District and the Fritz-Haber-Institut

Sketch of the south-west border of Berlin today Berlin 1885 1908 Starting with a comparison of sciences in Prussia with that in France, England, and USA, Adolf von Harnack (a protestant theologian) suggested to the Kaiser to found research institutes named "Kaiser Wilhelm Institutes for Scientific Research". The Kaiser liked the idea and was fully supportive: 1910 "... We need institutions that exceed the boundaries of the universities and are unimpaired by the objectives of education, but in close association with academia and universities, serving only the purpose of research ... it is my desire to establish under my protectorate and under my name a society whose task it is to establish and maintain such institutes .... 1911 Foundation of the "KWI for Chemistry" and the "KWI for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry" (first director: Fritz Haber) -- about 10 more institutes were founded during the coming 10 years. 1 1912 Kaiser-Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry and for Physical- Chemistry and Electrochemistry -- Most right: Villa of Fritz Haber. Kaiser Wilhelm II, Adolf von Harnack, followed by Emil Fischer and Fritz Haber walking to the opening cere- mony of the first two KWG institutes October 1912 Arial view of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institutes for "Chemistry" and for "Physical-Chemistry and Electrochemistry" -- around 1918 2 A glimpse at the history of the Fritz-Haber- Institute of the Max-Planck-Gesellschaft 1911 Foundation of the Kaiser- Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electro- chemistry (first director: Fritz Haber) 1914 Research and production -1918 of chemical weapons (mustard gas, etc.) 1918 Haber received the Nobelprize for the development of the ammonia synthesis Fritz Haber and 1933 Haber leaves Germany Albert Einstein at (see also FHI- webpages: history and the "FHI" -- 1915 2 brief PBS reports.) A glimpse at the history of the Fritz-Haber- Institute of the Max-Planck-Gesellschaft 1911 Foundation of the Kaiser-Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry (1. -

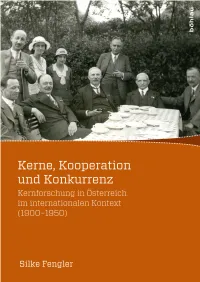

Kerne, Kooperation Und Konkurrenz. Kernforschung In

Wissenschaft, Macht und Kultur in der modernen Geschichte Herausgegeben von Mitchell G. Ash und Carola Sachse Band 3 Silke Fengler Kerne, Kooperation und Konkurrenz Kernforschung in Österreich im internationalen Kontext (1900–1950) 2014 Böhlau Verlag Wien Köln Weimar The research was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) : P 19557-G08 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Datensind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Umschlagabbildung: Zusammentreffen in Hohenholte bei Münster am 18. Mai 1932 anlässlich der 37. Hauptversammlung der deutschen Bunsengesellschaft für angewandte physikalische Chemie in Münster (16. bis 19. Mai 1932). Von links nach rechts: James Chadwick, Georg von Hevesy, Hans Geiger, Lili Geiger, Lise Meitner, Ernest Rutherford, Otto Hahn, Stefan Meyer, Karl Przibram. © Österreichische Zentralbibliothek für Physik, Wien © 2014 by Böhlau Verlag Ges.m.b.H & Co. KG, Wien Köln Weimar Wiesingerstraße 1, A-1010 Wien, www.boehlau-verlag.com Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dieses Werk ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist unzulässig. Lektorat: Ina Heumann Korrektorat: Michael Supanz Umschlaggestaltung: Michael Haderer, Wien Satz: Michael Rauscher, Wien Druck und Bindung: Prime Rate kft., Budapest Gedruckt auf chlor- und säurefrei gebleichtem Papier Printed in Hungary ISBN 978-3-205-79512-4 Inhalt 1. Kernforschung in Österreich im Spannungsfeld von internationaler Kooperation und Konkurrenz ....................... 9 1.1 Internationalisierungsprozesse in der Radioaktivitäts- und Kernforschung : Eine Skizze ...................... 9 1.2 Begriffsklärung und Fragestellungen ................. 10 1.2.2 Ressourcenausstattung und Ressourcenverteilung ......... 12 1.2.3 Zentrum und Peripherie ..................... 14 1.3 Forschungsstand ........................... 16 1.4 Quellenlage ............................. -

Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Werner Heisenberg And

MAX-PLANCK-INSTITUT FÜR WISSENSCHAFTSGESCHICHTE Max Planck Institute for the History of Science PREPRINT 203 (2002) Horst Kant Werner Heisenberg and the German Uranium Project Otto Hahn and the Declarations of Mainau and Göttingen Werner Heisenberg and the German Uranium Project* Horst Kant Werner Heisenberg’s (1901-1976) involvement in the German Uranium Project is the most con- troversial aspect of his life. The controversial discussions on it go from whether Germany at all wanted to built an atomic weapon or only an energy supplying machine (the last only for civil purposes or also for military use for instance in submarines), whether the scientists wanted to support or to thwart such efforts, whether Heisenberg and the others did really understand the mechanisms of an atomic bomb or not, and so on. Examples for both extreme positions in this controversy represent the books by Thomas Powers Heisenberg’s War. The Secret History of the German Bomb,1 who builds up him to a resistance fighter, and by Paul L. Rose Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project – A Study in German Culture,2 who characterizes him as a liar, fool and with respect to the bomb as a poor scientist; both books were published in the 1990s. In the first part of my paper I will sum up the main facts, known on the German Uranium Project, and in the second part I will discuss some aspects of the role of Heisenberg and other German scientists, involved in this project. Although there is already written a lot on the German Uranium Project – and the best overview up to now supplies Mark Walker with his book German National Socialism and the quest for nuclear power, which was published in * Paper presented on a conference in Moscow (November 13/14, 2001) at the Institute for the History of Science and Technology [àÌÒÚËÚÛÚ ËÒÚÓËË ÂÒÚÂÒÚ‚ÓÁ̇ÌËfl Ë ÚÂıÌËÍË ËÏ. -

Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project, 1939-1945: a Study in German Culture

Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project http://content.cdlib.org/xtf/view?docId=ft838nb56t&chunk.id=0&doc.v... Preferred Citation: Rose, Paul Lawrence. Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project, 1939-1945: A Study in German Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1998 1998. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft838nb56t/ Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project A Study in German Culture Paul Lawrence Rose UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford © 1998 The Regents of the University of California In affectionate memory of Brian Dalton (1924–1996), Scholar, gentleman, leader, friend And in honor of my father's 80th birthday Preferred Citation: Rose, Paul Lawrence. Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project, 1939-1945: A Study in German Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1998 1998. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft838nb56t/ In affectionate memory of Brian Dalton (1924–1996), Scholar, gentleman, leader, friend And in honor of my father's 80th birthday ― ix ― ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For hospitality during various phases of work on this book I am grateful to Aryeh Dvoretzky, Director of the Institute of Advanced Studies of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, whose invitation there allowed me to begin work on the book while on sabbatical leave from James Cook University of North Queensland, Australia, in 1983; and to those colleagues whose good offices made it possible for me to resume research on the subject while a visiting professor at York University and the University of Toronto, Canada, in 1990–92. Grants from the College of the Liberal Arts and the Institute for the Arts and Humanistic Studies of The Pennsylvania State University enabled me to complete the research and writing of the book. -

Otto Hahn Medal 2015

Outstanding! Junior scientists of the Max Planck Society June 2016, Saarbrücken Contents Foreword ......................... 2 The Otto Hahn Medal .......... 4 – 35 The Otto Hahn Award .............36 The Dieter Rampacher Prize .......40 The Nobel Laureate Fellowship ....42 The Reimar Lüst Fellowship ........48 Impressum ......................49 1 Outstanding! The Max Planck Society is always on the lookout for the most creative, innovative minds in almost every discipline of the basic sciences. We offer such pioneers ideal conditions for the achieve ment of their research goals. From the Directors to our doctoral students, Max Planck researchers of all career stages have the courage and intellec tual strength to open up new chapters in science. Especially in the case of junior scientists, our aim is to make them more aware of their own abilities and to encourage them to find their own way in research. Support of junior scientists is there fore an essential element of the Max Planck Society. We are fully aware that the same universal law holds true in science as elsewhere: the future depends on the upandcoming generation! The level at which our junior scientists pursue their research is consistently high across all 83 Institutes. Nevertheless, every year we single out a small number of junior scientists whose achievements we deem to be particularly out standing. They have succeeded – right at the start of their careers – in demonstrating a high degree of scientific creativity. The laureates featured in this booklet will be honoured at a ceremony at the 2016 Annual General Meeting in Saarbrücken in the presence of all the members of the Max Planck Society. -

Hitler's Uranium Club, the Secret Recordings at Farm Hall

HITLER’S URANIUM CLUB DER FARMHALLER NOBELPREIS-SONG (Melodie: Studio of seiner Reis) Detained since more than half a year Ein jeder weiss, das Unglueck kam Sind Hahn und wir in Farm Hall hier. Infolge splitting von Uran, Und fragt man wer is Schuld daran Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. The real reason nebenbei Die energy macht alles waermer. Ist weil we worked on nuclei. Only die Schweden werden aermer. Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. Die nuclei waren fuer den Krieg Auf akademisches Geheiss Und fuer den allgemeinen Sieg. Kriegt Deutschland einen Nobel-Preis. Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. Wie ist das moeglich, fragt man sich, In Oxford Street, da lebt ein Wesen, The story seems wunderlich. Die wird das heut’ mit Thraenen lesen. Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. Die Feldherrn, Staatschefs, Zeitungsknaben, Es fehlte damals nur ein atom, Ihn everyday im Munde haben. Haett er gesagt: I marry you madam. Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. Even the sweethearts in the world(s) Dies ist nur unsre-erste Feier, Sie nennen sich jetzt: “Atom-girls.” Ich glaub die Sache wird noch teuer, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. -

Selbstreflexionen Deutscher Atomphysiker. Die Farm Hall

MARK WALKER SELBSTREFLEXIONEN DEUTSCHER ATOMPHYSIKER Die Farm Hall-Protokolle und die Entstehung neuer Legenden um die „deutsche Atombombe" Das deutsche Bemühen um die Nutzung der Kernspaltung bleibt eine der meistdisku tierten Episoden in der jüngeren Wissenschaftsgeschichte1. Ein besonders umstrittener Aspekt in der Geschichte der „deutschen Atombombe" ist dabei die Debatte über die mysteriösen und schwer zu erfassenden „Farm Hall-Aufnahmen", die nach dem Krieg ohne Wissen der zehn im englischen Farm Hall festgehaltenen deutschen Naturwis senschaftler erstellt wurden. Die „Gäste" waren Erich Bagge, Kurt Diebner, Walther Gerlach, Otto Hahn, Paul Harteck, Werner Heisenberg, Horst Korsching, Max von Laue, Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker und Karl Wirtz. In einem Schreiben an den Britischen Lordkanzler vom November 1991 forderten rund zwanzig renommierte Naturwissenschaftler und Historiker, angeführt von Nicholas Kurti, Rudolf Peierls und Margaret Gowing, darunter auch die Präsidenten der Royal Society sowie der British Academy, die Freigabe der Farm Hall-Aufnah men2. Wenige Monate später gab das Public Record Office in London ein 212 Seiten starkes Transkript jener „Operation Epsilon" frei, wie der Deckname der Lausch aktion gelautet hatte3. Kurz darauf stellte auch das amerikanische Nationalarchiv in 1 Vgl. Mark Walker, Die Uranmaschine. Mythos und Wirklichkeit der deutschen Atombombe, Berlin 1990; ders., Legenden um die deutsche Atombombe, in: VfZ 38 (1990), S. 45-74; ders., Physics and Propaganda: Werner Heisenberg's Foreign Lectures under National Socialism, in: Historical Studies in the Physical and Biological Sciences 22 (1992), S. 339-389. Ich möchte Paul Forman, Barbara Sul- livan und Andreas Wirsching für ihre Hilfe danken. 2 The Farm Hall Transcripts (siehe Anm. 4), S. -

Nazi Secret Weapons and the Cold War Allied Legend

Nazi Secret Weapons and the Cold War Allied Legend http://myth.greyfalcon.us/sun.htm by Joseph P. Farrell GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG "A comprehensive February 1942 (German) Army Ordnance report on the German uranium enrichment program includes the statement that the critical mass of a nuclear weapon lay between 10 and 100 kilograms of either uranium 235 or element 94.... In fact the German estimate of critical mass of 10 to 100 kilograms was comparable to the contemporary Allied estimate of 2 to 100.... The German scientists working on uranium neither withheld their figure for critical mass because of moral scruples nor did they provide an inaccurate estimate as the result of gross scientific error." --Mark Walker, "Nazi Science: Myth, Truth, and the German Atomic Bomb" A Badly Written Finale "In southern Germany, meanwhile, the American Third and Seventh and the French First Armies had been driving steadily eastward into the so-called 'National Redoubt'.... The American Third Army drove on into Czechoslovakia and by May 6 had captured Pilsen and Karlsbad and was approaching Prague." --F. Lee Benns, "Europe Since 1914 In Its World Setting" (New York: F.S. Crofts and Co., 1946) On a night in October 1944, a German pilot and rocket expert by the same of Hans Zinsser was flying his Heinkel 111 twin-engine bomber in twilight over northern Germany, close to the Baltic coast in the province of Mecklenburg. He was flying at twilight to avoid the Allied fighter aircraft that at that time had all but undisputed mastery of the skies over Germany. Little did he know that what he saw that night would be locked in the vaults of the highest classification of the United States government for several decades after the war. -

The Virus House -

David Irving The Virus House - F FOCAL POINT Copyright © by David Irving Electronic version copyright © by Parforce UK Ltd. All rights reserved No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. Copies may be downloaded from our website for research purposes only. No part of this publication may be commercially reproduced, copied, or transmitted save with written permission in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act (as amended). Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. To Pilar is the son of a Royal Navy commander. Imper- fectly educated at London’s Imperial College of Science & Tech- nology and at University College, he subsequently spent a year in Germany working in a steel mill and perfecting his fluency in the language. In he published The Destruction of Dresden. This became a best-seller in many countries. Among his thirty books (including three in German), the best-known include Hitler’s War; The Trail of the Fox: The Life of Field Marshal Rommel; Accident, the Death of General Sikorski; The Rise and Fall of the Luftwaffe; Göring: a Biography; and Nuremberg, the Last Battle. The second volume of Churchill's War appeared in and he is now completing the third. His works are available as free downloads at www.fpp.co.uk/books. Contents Author’s Introduction ............................. Solstice.......................................................... A Letter to the War Office ........................ The Plutonium Alternative....................... An Error of Consequence ......................... Item Sixteen on a Long Agenda............... Freshman................................................... Vemork Attacked..................................... -

Bruno Touschek in Germany After the War: 1945-46

LABORATORI NAZIONALI DI FRASCATI INFN–19-17/LNF October 10, 2019 MIT-CTP/5150 Bruno Touschek in Germany after the War: 1945-46 Luisa Bonolis1, Giulia Pancheri2;† 1)Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Boltzmannstraße 22, 14195 Berlin, Germany 2)INFN, Laboratori Nazionali di Frascati, P.O. Box 13, I-00044 Frascati, Italy Abstract Bruno Touschek was an Austrian born theoretical physicist, who proposed and built the first electron-positron collider in 1960 in the Frascati National Laboratories in Italy. In this note we reconstruct a crucial period of Bruno Touschek’s life so far scarcely explored, which runs from Summer 1945 to the end of 1946. We shall describe his university studies in Gottingen,¨ placing them in the context of the reconstruction of German science after 1945. The influence of Werner Heisenberg and other prominent German physicists will be highlighted. In parallel, we shall show how the decisions of the Allied powers, towards restructuring science and technology in the UK after the war effort, determined Touschek’s move to the University of Glasgow in 1947. Make it a story of distances and starlight Robert Penn Warren, 1905-1989, c 1985 Robert Penn Warren arXiv:1910.09075v1 [physics.hist-ph] 20 Oct 2019 e-mail: [email protected], [email protected]. Authors’ ordering in this and related works alternates to reflect that this work is part of a joint collaboration project with no principal author. †) Also at Center for Theoretical Physics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, USA. Contents 1 Introduction2 2 Hamburg 1945: from death rays to post-war science4 3 German science and the mission of the T-force6 3.1 Operation Epsilon .