Florida Historical Quarterly, Volume 90, Number 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jews, Radical Catholic Traditionalists, and the Extreme Right

“Artisans … for Antichrist”: Jews, Radical Catholic Traditionalists, and the Extreme Right Mark Weitzman* The Israeli historian, Israel J. Yuval, recently wrote: The Christian-Jewish debate that started nineteen hundred years ago, in our day came to a conciliatory close. … In one fell swoop, the anti-Jewish position of Christianity became reprehensible and illegitimate. … Ours is thus the first generation of scholars that can and may discuss the Christian-Jewish debate from a certain remove … a post- polemical age.1 This appraisal helped spur Yuval to write his recent controversial book Two Nations in Your Womb: Perceptions of Jews and Christians in late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Yuval based his optimistic assessment on the strength of the reforms in Catholicism that stemmed from the adoption by the Second Vatican Council in 1965 of the document known as Nostra Aetate. Nostra Aetate in Michael Phayer’s words, was the “revolution- ary” document that signified “the Catholic church’s reversal of its 2,000 year tradition of antisemitism.”2 Yet recent events in the relationship between Catholics and Jews could well cause one to wonder about the optimism inherent in Yuval’s pronouncement. For, while the established Catholic Church is still officially committed to the teachings of Nostra Aetate, the opponents of that document and of “modernity” in general have continued their fight and appear to have gained, if not a foothold, at least a hearing in the Vatican today. And, since in the view of these radical Catholic traditionalists “[i]nternational Judaism wants to radically defeat Christianity and to be its substitute” using tools like the Free- * Director of Government Affairs, Simon Wiesenthal Center. -

Vatican Secret Diplomacy This Page Intentionally Left Blank Charles R

vatican secret diplomacy This page intentionally left blank charles r. gallagher, s.j. Vatican Secret Diplomacy joseph p. hurley and pope pius xii yale university press new haven & london Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Copyright © 2008 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Scala and Scala Sans by Duke & Company, Devon, Pennsylvania. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gallagher, Charles R., 1965– Vatican secret diplomacy : Joseph P. Hurley and Pope Pius XII / Charles R. Gallagher. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-12134-6 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Hurley, Joseph P. 2. Pius XII, Pope, 1876–1958. 3. World War, 1939–1945— Religious aspects—Catholic Church. 4. Catholic Church—Foreign relations. I. Title. BX4705.H873G35 2008 282.092—dc22 [B] 2007043743 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Com- mittee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To my father and in loving memory of my mother This page intentionally left blank contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 1 A Priest in the Family 8 2 Diplomatic Observer: India and Japan, 1927–1934 29 3 Silencing Charlie: The Rev. -

The Priestly Patriotic Associations in the Eastern European Countries

231 Pregledni znanstveni članek (1.02) BV 68 (2008) 2, 231-256 UDK 272-784-726.3(4-11)«194/199« Bogdan Kolar SDB The Priestly Patriotic Associations in the Eastern European Countries Abstract: The priestly patriotic associations used to be a part of the every day life of the Catholic Church in the Eastern European countries where after World War II Com- munist Parties seized power putting in their programmes the elimination of the Catho- lic Church from the public life and in the final analysis the destruction of the religion in general. In spite of the fact that the associations were considered professional guilds of progressive priests with a particular national mission they were planned by their founders or instigators (mainly coming from various secret services and the offices for religious affairs) as a means of internal dissension among priests, among priests and bishops, among local Churches and the Holy See, and in the final stage also among the leaders of church communities and their members. A special attention of the totalitarian authorities was dedicated to the priests because they were in touch with the population and the most vulnerable part of the Church structures. To perform their duties became impossible if their relations with the local authorities as well as with the repressive in- stitutions were not regulated or if the latter set obstacles in fulfilling their priestly work. Taking into account the necessary historic and social context, the overview of the state of the matters in Yugoslavia (Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Croatia), Hungary, Poland and Czechoslovakia demonstrates that the instigators of the priestly patriotic so- cieties followed the same pattern, used the same methods and defined the same goals of their activities. -

Bogdan Kolar, Regens Nuntiaturae Mons. Joseph Patrick Hurley In

7 Razprave Pregledni znanstveni članek (1.02) Bogoslovni vestnik 77 (2017) 1,7—38 UDK: 272-9(497.4)“19“ Besedilo prejeto: 4/2017; sprejeto: 5/2017 Bogdan Kolar Regens nuntiaturae mons. Joseph Patrick Hurley in katoliška Cerkev v Sloveniji Povzetek: Po spremembi politične ureditve v Jugoslaviji s koncem druge svetovne vojne je bilo treba urediti tudi vprašanje odnosov s Svetim sedežem. Jugoslo- vanske oblasti so iskale priznanje Svetega sedeža, pri tem pa so imele pred očmi mednarodni pomen takšne odločitve. Papež Pij XII. je kot svojega osebnega po- slanca v Jugoslaviji imenoval ameriškega škofa mons. Josepha P. Hurleyja, ki se je enoumno postavil na stran katoliške Cerkve in ni opravičil pričakovanj državnih oblasti. Zato so kmalu nastale napetosti, ki so povzročile, da je po dobrih treh letih zapustil državo. Predtem je rešil vprašanje imenovanja nekaterih škofov, tudi v obeh slovenskih škofijah, uredil cerkvene strukture in se tudi drugače za- vzel za pravice Cerkve proti prevelikemu poseganju države na cerkveno področje. Katoliški škofje so v njem našli močnega podpiratelja in vez s Svetim sedežem. Stike z njim so ohranili še po njegovi vrnitvi na sedež sv. Avguština na Floridi. Ključne besede: mons. Joseph P. Hurley (1894–1967), papež Pij XII. (1876–1958), katoliška Cerkev, Slovenija Abstract: Regens Nuntiaturae Mons. Joseph Patrick Hurley and the Catholic Church in Slovenia Due to the change of the political system in Yugoslavia after the end of World War II it was necessary to find a new settlement of the relations between the state and the Holy See. The Yugoslav authorities were trying to be recognized by the Holy See, considering above all the international meaning of such a de- cision. -

Download the Florida Civil War Heritage Trail

Florida -CjvjlV&r- Heritage Trail .•""•^ ** V fc till -/foMyfa^^Jtwr^— A Florida Heritage Publication Florida . r li //AA Heritage Trail Fought from 1861 to 1865, the American Civil War was the country's bloodiest conflict. Over 3 million Americans fought in it, and more than 600,000 men, 2 percent of the American population, died in it. The war resulted in the abolition of slavery, ended the concept of state secession, and forever changed the nation. One of the 1 1 states to secede from the Union and join the Confederacy, Florida's role in this momentous struggle is often overlooked. While located far from the major theaters of the war, the state experienced considerable military activity. At one Florida battle alone, over 2,800 Confederate and Union soldiers became casualties. The state supplied some 1 5,000 men to the Confederate armies who fought in nearly all of the major battles or the war. Florida became a significant source of supplies for the Confederacy, providing large amounts of beef, pork, fish, sugar, molasses, and salt. Reflecting the divisive nature of the conflict, several thousand white and black Floridians also served in the Union army and navy. The Civil War brought considerable deprivation and tragedy to Florida. Many of her soldiers fought in distant states, and an estimated 5,000 died with many thousands more maimed and wounded. At home, the Union blockade and runaway inflation meant crippling scarcities of common household goods, clothing, and medicine. Although Florida families carried on with determination, significant portions of the populated areas of the state lay in ruins by the end of the war. -

US BISHOPS.Docx

Alabama Bishop of Holy Protection of Mary Byzantine Catholic Eparchy of Phoenix Archdiocese of Mobile 400 Government Street Diocese of Phoenix Mobile, AL 36602 400 East Monroe Street http://www.mobilearchdiocese.org/ Phoenix, AZ 85004-2336 Archbishop Thomas J. Rodi http://www.diocesephoenix.org/ Archbishop of Mobile Bishop Thomas J. Olmsted Diocese of Birmingham Bishop of Phoenix 2121 3rd Avenue North Bishop Eduardo A. Nevares P.O. Box 12047 Auxiliary Bishop of Phoenix Birmingham, AL 35202-2047 http://www.bhmdiocese.org/ Diocese of Tucson Bishop Steven J. Raica P.O. Box 31 Bishop of Birmingham Tucson, AZ85702 Bishop Robert J. Baker http://www.diocesetucson.org/ Bishop Emeritus of Birmingham Bishop Edward J. Weisenburger Bishop of Tucson Bishop Gerald F. Kicanas Alaska Bishop Emeritus of Tucson Archdiocese of Anchorage-Juneau 225 Cordova Street Arkansas Anchorage, AK 99501-2409 http://www.aoaj.org Diocese of Little Rock Archbishop Andrew E. Bellisario CM 2500 N. Tyler Street Archbishop of Anchorage-Juneau Little Rock, AR 72207 Archbishop Roger L. Schwietz OMI http://www.dolr.org/ Archbishop Emeritus of Anchorage Bishop Anthony B. Taylor Diocese of Fairbanks Bishop of Little Rock 1316 Peger Road Fairbanks, AK 99709-5199 California http://www.cbna.info/ Bishop Chad Zielinski Armenian Catholic Eparchy of Our Lady of Bishop of Fairbanks Nareg in the USA & Canada 1510 East Mountain St Arizona Glendale, CA 91207 http://www.armeniancatholic.org/inside.ph Holy Protection of Mary Byzantine Catholic p?lang=en&page_id=304 Eparchy of Phoenix Bishop Mikaël Mouradian 8105 North 16th Street Eparch of the Armenian Catholic Eparchy of Phoenix, AZ 85020 Our Lady of Nareg http://www.eparchyofphoenix.org/ Bishop Manuel Batakian Bishop John Stephen Pazak C.Ss.R Bishop Emeritus of Our Lady of Nareg in Archdiocese of San Francisco New York of Armenian Catholics One Peter Yorke Way Chaldean Catholic Eparchy of St. -

Nuacht Feb. 14.Indd

Community Newsletter of St. Patrick’s Society of MontrealNUACHT Joe Mell: Irishman of the Year By Kathleen Dunn t is fitting that Joe Mell, the 2014 Photo: Irishman of the Year, was born on St.I Patrick’s Day. Well actually, he Forrest Anne quips, “at 11:45 p.m. on March 16th, 1932, in Montreal, it was already St. Patrick’s Day in Ireland.” The title Irishman of the Year has been awarded annually since 1976 by the Erin Sports Association. Its President, Tim Furlong, explains that Joe was “the unanimous choice” of the 80-member organization. “He’s very, very deserving,” Tim adds, “and I’m shocked that he’s not been Irishman in the past.” He was chosen in recognition of what he has done for the Irish community in Montreal, the general community, and in particular Joe Mell being sashed by Bill Hurley, the 2012 Irishman of the year. for Point St. Charles. The list of his accomplishments is very long Family and friends and the youngsters they coached rallied together indeed. and named themselves “Leo’s Boys” to pursue the vision. Joe has been a life-long resident of “The Joe put his fundraising skills to work to make sure that as many Point” and has remained true to his roots. children as possible could participate, at no charge to their parents, in His community involvement began when he organized sports. He is particularly proud of the fact that there was was 16, coaching a softball team of 11-and- never a paid staff member with Leo’s Boys during its 35 years of 12-year-olds in the Point with his brother minor sports operations. -

Download the Irish American List Here

“ Here come the IRISH“ NEW JERSEY’S LEADERS 2019 MAKE OUR STATE A BETTER PLACE! HERE COME THE IR ISH ! New Jersey’s Leaders 2019 St. Patrick’s Day is once again upon us with its month long festivities. To help celebrate the occasion, InsiderNJ.com presents its annual and profiled list of New Jersey’s Irish American leaders and activists as a salute to the holiday and as a harbinger of long awaited springtime. The annual tribute to the ‘Irish High Holy Days’ is an acknowledgement of accomplishments, numerous contributions and community service. Once again, the list includes both veterans of previous compilations and quite a few newcomers, as well. Collectively, they have all demonstrated a commitment to their Irish American heritage. The updated list is compiled to commemorate the 84th Anniversary of the Newark St. Patrick’s Day Parade, the oldest Irish American march in New Jersey (1936-present), interrupted only by WWII (1943-46). This year’s Irish march in downtown Newark is scheduled for Friday, March 15 at 1:00pm. Grand Marshal Sean O’Neill and Deputy Grand Marshal Kathleen M. Conlon have been elected by delegates to lead the parade. The 2019 Newark Parade is dedicated to Thomas J. Gartland (1939-2018) Tom Barrett, compiler of the list, credits the Newark parade for its sense of tradition and staying power. His father, Thomas P. J. Barrett, a journalist and World War II veteran, was a three-time parade chairman. The list is purely subjective. WE HOPE YOU ENJOY IT! WILLIAM (BILL) BARONI JOSEPH P. BRENNAN, ESQ. -

May 16Th, 2021 Bulletin

Saint Agnes Catholic Church The Ascension of the Lord — May 16th, 2021 From the Gospel of Mark So then the Lord Jesus, after he spoke to them, was taken up into heaven and took his seat at the right hand of God. But they went forth and preached everywhere, while the Lord worked with them and confirmed the word through accompanying signs. Mk 16:15-20 This Week’s Mass Intentions Scripture Readings Sunday, May 16 Week of May 16th, 2021 8:00 a.m. Mothers Day Novena Sunday Solemnity of the Ascension of the Lord Acts 1:1-11; Ps 47:2-3, 6-7, 8-9; Eph 1:17-23 10:00 a.m. All Living and Deceased Parishioners or Eph 4:1-13 or 4:1-7, 11-13; Mk 16:15-20 12:00 p.m. Jose Ricardo Monday Acts 19:1-8; Ps 68:2-3ab, 4-5acd, 6-7ab; (Irene Brown) Jn 16:29-33 Tuesday Saint John I, Pope and Martyr Monday, May 17 Acts 20:17-27; Ps 68:10-11, 20-21; Jn 17:1-11a 6:30 a.m. Mothers Day Novena Wednesday Acts 20:28-38; Ps 68:29-30, 33-35a, 35bc- 9:00 a.m. Mr. Unwali 36ab; Jn 17:11b-19 (Margaret Breighner Thursday Saint Bernardine of Siena, Priest Acts 22:30; 23:6-11; Ps 16:1-2a and 5, 7-8, Tuesday, May 18 9-10, 11; Jn 17:20-26 6:30 a.m. Ignacio Flores Friday Saint Christopher Magallanes, Priest, and (Sainz Family) Companions, Martyrs Acts 25:13b-21; Ps 103:1-2, 11-12, 19-20ab; 9:00 a.m. -

Communion Breakfast – Sunday, April 22 Most Reverend Neal J

Vol. 53 No. 1 Spring 2012 Communion Breakfast – Sunday, April 22 Most Reverend Neal J. Buckon ’71 – Man of the Year Bishop Neal Buckon Platoon Leader and Transportation Officer in the graduated from Gesu Headquarters and Headquarters Company of the Allied Command Europe, Mobile Force (Land) (AMFL) (including Elementary School in deployments to Denmark, England, and Norway). University Heights and Cathedral Latin High Following seven years of active duty, he resigned his School. He continued commission and traveled to more than 100 countries. Inspired by these travels Neal entered the ministry. He earned a his education at John Bachelor of Arts degree in History from Cleveland State Carroll University, University, and a Bachelor of Arts degree in Philosophy from earning a Bachelor of Borromeo College of Ohio. He later received a Masters of Science degree through Divinity degree and a Master of Arts degree in Church History from Saint Mary’s Seminary in Cleveland, Ohio. his participation in the Following his graduate theological studies, he was ordained a ROTC program at priest in May 1995 for the Diocese of Cleveland and assigned Carroll. “Even before to Saint Margaret Mary Church in South Euclid, Ohio. While college, I knew I wanted in the seminary, he served in the U.S. Army Reserve as a Chaplain Candidate and was subsequently accessioned into to be in ROTC,” Bishop Buckon says. “It wasn’t the U.S. Army Chaplain Corps in 1996. something that was popular at the time with Vietnam, but my grandfather and other family members served. I His Chaplain assignments included locations around the felt every citizen ought to consider being of service.” world. -

US-State-Dept.-Ltr.Pdf

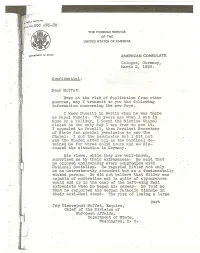

--.-"~--- ~~L."{ REFER TO ") : ':CiNo.BOO j..Ji['t{.-Rlvf· THE FOREIGN SERVICE OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AMERICAN CONSULATE Oologne, Germany, March 3, 1939. Confiden tial. I knew 'Pacelli·in Berlin 1Hhen he· was there as Papal llm1.cio. 'Tvvo years ago when I \vasJn Rome on a holiday, .I··found the Sistine Chapel closed oritlie only (lay'I Was' fre~ to see it. I appealed to Pacelli, then Cardinal Secr.etary of state for special permission to see the Chapel. I got the peYillissionbut I did not ,, see the Chapel after all as the Oardinalde~. tained me for ,three solid hOlITS and we dis• cussed the situation in GerQBnYo . His views, 'w4ile they are we 11:"YJlovm , surprised me by their extremeness. lIe said that he opposed ~~alterably every cQmpromise with National Socialism. He regarded Hitler not only a~ an untrustworthy scoundrel but as a fundamentally wicked person. He.did not believe that Hitler was capable ofmoc1eratio'n and in spite of a:p-Pear~'1.ces wQUlc1 end up in the camp of the left-wing Nazi extremists when he began his career. He told me that he supported the GerillallCatholic bishops in their anti-Nazi stand. The risk of losing a large part Jay. 'PierrepoJ?,tMoffat, Esquire, Chief of the Division of EDl~opean Affairs, Department of.state, W~shington, D. C. '1' '.1 'l!:~I':.-J. Ls ,':ji. - 2 - part of the Catholic .youth in Germany, he said, was not as great as the consequences to .~he Catholic Church in general throughout the world in surrendering to the Nazis. -

Strengthening Ministry

Strengthening Ministry Sai nt Luke In stitu te Annual Report | July 1, 2019-June 30, 2020 Saint Luke Institute strengthens the psychological and spiritual well-being of Catholic clergy and religious. 1 Table of Contents Saint Luke In stitu te Sai nt Luke In stitu te “See, I am doing something new!” 3 Education: Meeting Needs in the Virtual World 4 When Opportunity Knocks: 2020 Virtual Benefit for Saint Luke Institute 6 Saint Luke Institute at a Glance 8 Operating Revenue, Expense, and Charity Care Provided 9 In Gratitude for Our Partners in Mission and Ministry 10 Giving Your Way 18 Analysis Leads to New Treatment Model 19 Save the date: The 2021 Saint Luke Benefit 20 Accreditation Saint Luke Institute is accredited by The Joint Commission and licensed by the State of Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. The Joint Commission Accreditation for behavioral health care organizations is a nationally recognized leader in accreditation. The Joint Commission is an independent, objective evaluator of care quality. Accreditation from the Joint Commission is a “gold seal of quality” and a mark of distinction for behavioral health organizations. Over many decades Saint Luke Institute has achieved this standard of quality. It is our commitment to the Catholic Church and its servants to provide quality care, treatment, and service. 2 “See, I am doing something new!” Saint Luke In stitu te Fr. David Songy, O.F.M.Cap., S.T.D., Psy.D. President and CEO Dear Friends in Christ, Christians celebrate time. We move through the seasons of Advent, Christmas, Ordinary Time, Lent, and Easter just as surely as we move through winter, spring, summer, and fall.