Part Two - 'Why Should We Protect Endangered Languages?' Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction Laurent Sagart, Roger Blench, Alicia Sanchez-Mazas

Introduction Laurent Sagart, Roger Blench, Alicia Sanchez-Mazas To cite this version: Laurent Sagart, Roger Blench, Alicia Sanchez-Mazas. Introduction. Laurent Sagart, Roger Blench et Alicia Sanchez-Mazas. The Peopling of East Asia: Putting together archaeology, linguistics and genetics, RoutledgeCurzon, pp.1-14, 2005. halshs-00104717 HAL Id: halshs-00104717 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00104717 Submitted on 9 Oct 2006 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. INTRODUCTION 5460 words In the past ten years or so, important advances in our understanding of the formation of East Asian populations, historical cultures and language phyla have been made separately by geneticists, physical anthropologists, archaeologists and linguists. In particular, the genetics of East Asian populations have become the focus of intense scrutiny. The mapping of genetic markers, both classical and molecular, is progressing daily: geneticists are now proposing scenarios for the initial settlement of East Asia by modern humans, as well as for population movements in more recent times. Chinese archaeologists have shown conclusively that the origins of rice agriculture are to be sought in the mid-Yangzi region around 10,000 BP and that a millet-based agriculture developed in the Huang He Valley somewhat later. -

Graphic Loans: East Asia and Beyond

This is a repository copy of Graphic loans: East Asia and beyond. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/77434/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Tranter, N. (2009) Graphic loans: East Asia and beyond. Word , 60 (1). pp. 1-37. ISSN 0043-7956 https://doi.org/10.1080/00437956.2009.11432591 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Graphic loans: East Asia and beyond Abstract. The national languages of East Asia (Chinese, Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese) have made extensive use of a type of linguistic borrowing sometimes referred to as a ‘graphic loan’. Such loans have no place in the conventional classification of loans based on Haugen (1950) or Weinreich (1953), and research on loan word theory and phonology generally overlooks them. -

East Asian Studies Program |

East Asian Studies Program and Department Annual Report 2016-17 Cover: Main section from “A Humorous Map of the World 歐洲大戰亂畫報 (其十六): 滑稽時局世界地圖” (inscribed, The Ōshū dai senran gahō no. 16). Printed in 1914. From the Princieton University Library collection of “Block Prints of the Chinese Revolu- tion,” given in 1937 by Donald Roberts, Class of 1909. Annual Report 2011-12 Contents Director’s Letter 4 Department and Program News 6 Language Programs 8 Undergraduates 10 Graduate Students 14 Faculty 18 Events 20 Summer Programs 28 Affiliated Programs 30 Beyond Princeton EAS 33 Libraries 34 Museum 37 In Memoriam: Professor Yu-kung Kao (1929-2016) Director’s Letter, 2016-17 East Asian Studies dates from the 1960s and 1970s, when Princeton established first a Program and then a Department focusing on the study of China, Japan, and Korea, including linguistic and disciplinary training. The Department comprises about forty faculty members and language instructors and offers a major, while the Program supports faculty and students working on East Asia in both the East Asian Studies Department and other departments. In 2016-17 the nearly forty undergraduates enrolled in East Asian Studies pursued many interests, combining breadth of study with a solid foundation in the languages of East Asia. The eleven majors in the East Asian Studies Department worked in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean languages and wrote theses covering political history, transnational cinema, trauma and narrative, economics, ethnicity and colonialism, literature and translation, educational inequality, and the politics of space exploration. Twenty-six majors in other departments who completed certificates in East Asian Studies (one offered by the Department and one by the Program) submitted independent work that ranged even more widely. -

Linguistics of East Asian Languages

2020/2021 Linguistics of East Asian Languages Code: 101540 ECTS Credits: 6 Degree Type Year Semester 2500244 East Asian Studies OB 3 2 The proposed teaching and assessment methodology that appear in the guide may be subject to changes as a result of the restrictions to face-to-face class attendance imposed by the health authorities. Contact Use of Languages Name: Makiko Fukuda Principal working language: catalan (cat) Email: [email protected] Some groups entirely in English: No Some groups entirely in Catalan: No Some groups entirely in Spanish: No Other comments on languages Part of Japan (Makiko Fukuda): Catalan, Part of China (Leonor Sola): Spanish Teachers Leonor Sola Comino Prerequisites None. Objectives and Contextualisation The aim of this subject is to introduce students to fundamental encyclopedic knowledge of issues related to two of the main languages of East Asia, Chinese and Japanese. On successfully completing this subject, students will be able to: Assimilate and understand the principles that govern language variation in East Asian languages. Identify, analyse, differentiate between, summarise and explain the principles that govern language variation in Chinese and Japanese. Determine the values, beliefs and ideologies expressed in oral and written texts in Chinese and Japanese. Apply linguistic, cultural and thematic knowledge to the analysis and comprehension of written texts in Chinese and Japanese. Apply knowledge of the values, beliefs and ideologies of East Asia to understand and appreciate written texts in Chinese and Japanese. Develop a critical way of thinking and reasoning, and communicate effectively, both in their own languages and a third language. Develop autonomous learning strategies. -

9 to Which Language Family Does Chinese Belong, Or What's in a Name?

9 To which language family does Chinese belong, or what's in a name? George van Driem There are at least five competing theories about the linguistic prehistory of Chinese. Two of them, Tibeto-Burman and Sino-Tibetan, originated in the beginning of the 19th century. Sino-Caucasian and Sino-Austronesian are products of the second half of the 20th century, and East Asian is an intriguing model presented in 2001. These terms designate distinct models of language relationship with divergent implications for the peopling of East Asia. What are the substantive differences between the models? How do the paradigms differently inform the direction of linguistic investigation and differently shape the formulation of research topics? What empirical evidence can compel us to decide between the theories? Which of the theories is the default hypothesis, and why? How can terminology be used in a judicious manner to avoid unwittingly presupposing the veracity of improbable or, at best, unsupported propositions? 1. The default hypothesis: Tibeto-Burman The first rigorous polyphyletic exposition of Asian linguistic stocks was presented in Paris by the German scholar Julius Heinrich von Klaproth in 1823. 1 His Asia Polyglotta was more comprehensive, extended beyond the confines ofthe Russian Empire and included major languages of East Asia, Southeast Asia and Polar America. Based on a systematic comparison of lexical roots, Klaproth identified and distinguished twenty-three Asian linguistic stocks, which he knew did not represent an exhaustive inventory. Yet he argued for a smaller number of phyla because he recognized the genetic affinity between certain of these stocks and the distinct nature of others. -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2018–19 From the Director his year we mark the fifth year of the Lieberthal-Rogel Center for Chinese Studies. The Center was established in 1961 with foundation Tgrants from the Mellon and Ford Foundations, and support from the US Department of Education. The 2014 Rogel Endowment further strength- ened our capacity to offer innovative programming, to fund cutting-edge research on China across the disciplines, to host visiting scholars, postdoctoral fellows, and distinguished practitioners, and, finally, to offer Michigan graduate and undergraduate students internship, research and educational opportunities in China. At this fifth-year juncture, this report summarizes the full range of the Center’s activities since 2014. In particular I want to highlight one of our new programs funded via the Rogel Endowment. The Lieberthal-Rogel Postdoctoral Fellowship has thus far hosted twelve early-career academics. The postdoctoral program runs for two years and the fellows are integrated into the UM Community, both at the Center and at their disciplinary homes where they often teach and take part in seminars and workshops. Our fellows come from diverse disciplinary backgrounds—archeology, comparative literature, political science, to name a few. Their presence at the Center has been transformative for our graduate students and faculty, facilitating new collaborations, mentoring, and joint research. In turn, the Center has University of Michigan Lieberthal-Rogel University been a formative experience for young faculty members as they make the transition from graduate student to faculty positions, think tanks, and even the private sector. We now have former fellows placed at New York University, University of Notre Dame, Hoover Institution, and Facebook as well as many other places. -

Review Article

Review article Language and dialect in China Norbert Francis Northern Arizona University In the study of language learning, researchers sometimes ask how languages in contact are related. They compare the linguistic features of the languages, how the mental grammars of each language sub‑system are represented, put to use in performance, and how they interact. Within a linguistic family, languages can be closely related or distantly related, an interesting factor, for example, in understanding bilingualism and second language development. Dialects, on the other hand, are considered to be variants of the same language. While there is no way to always draw a sharp line between the categories of language and dialect, it is necessary to distinguish between the two kinds of language variation by the application of uniform criteria. The distinction between dialect and language is important for designing bilingual instructional programs, both for students who already speak two languages and for beginning second language learners. Keywords: dialect, language contact, language policy, minority languages, biliteracy, Chinese Introduction Researchers of language learning do not often delve into questions about how lan‑ guages and their varieties are related. One topic of debate however, due in part to widespread commentary outside of the field, often presents itself for explanation: the distinction between the categories of language and dialect. Sociolinguists for their part have contributed most notably to the task of distinguishing in a prin‑ cipled way between these categories; and a clear understanding is important for the study of language learning and for the broader discipline of applied linguistics. This article will present the case for continuing to uphold the traditional concep‑ tion underlying this distinction. -

UC Santa Barbara Himalayan Linguistics

UC Santa Barbara Himalayan Linguistics Title Direct Speech as a Rhetorical Style in Chantyal Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0rx8d1vt Journal Himalayan Linguistics, 6(0) Author Noonan, Michael Publication Date 2006 DOI 10.5070/H96023030 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Direct Speech as a Rhetorical Style in Chantyal Michael Noonan University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee 1.0 Introduction: Anyone who has had the experience of learning — or better yet, describing — a language other than his or her native language is quickly made to realize that languages can ‘package’ information in rather different ways. So, for example, fluent speakers of two languages, both trying to respond verbally to the same situation, might do so efficiently and yet quite differently. Indeed, bilinguals often report that they engage in different kinds of thinking when they shift languages, and these shifts in thinking can result in rather different modes of expression in the bilingual’s two languages. Putting aside purely ‘cultural’ differences in perception of events, such as imputations of motive, notions of appropriateness, and so on, and focusing instead on purely linguistic differences — difficult [or impossible] though these may be to disentangle in practice — we find that languages differ not just in the grammatical form in which descriptions of situations are packaged, but also in the amount of information and the kind of information that they contain. This sense that speakers of different languages engage in different sorts of thought processes can be explained with Slobin’s (1987, 1996a) hypothesis of ‘thinking for speaking’, thinking generated because of the requirements of the linguistic code. -

Clause Structure in South Asian Languages: General Introduction

V. DAYAL AND A. MAHAJAN CLAUSE STRUCTURE IN SOUTH ASIAN LANGUAGES: GENERAL INTRODUCTION 1. SOUTH ASIAN LANGUAGES IN GENERATIVE GRAMMAR “There is a tension between the demands of descriptive and explanatory adequacy. To achieve the latter, it is necessary to restrict available descriptive mechanisms so that few languages are accessible…To achieve descriptive adequacy, however, the available devices must be rich and diverse enough to deal with the phenomena exhibited in the possible human languages. We therefore face conflicting requirements. We might identify the field of generative grammar, as an area of research, with the domain in which this tension remains unresolved” (Chomsky 1986). Chomsky’s characterization of the role of empirical work in theoretical linguistics provides a good introduction to this volume of papers on the clause structure of South Asian languages. The search for principles to account for universal properties of language and the identification of parameters along which variation may occur, at the heart of the generative enterprise, cannot be carried out without balancing the twin requirements of descriptive and explanatory adequacy. Insights from various languages and language families have thus informed the generative research program since its inception approximately fifty years ago. South Asian languages have been studied within the generative paradigm since the sixties but it was in the eighties and nineties that they began to have a critical impact on the development of grammatical theory. Research by a number of scholars including K.P. Mohanan (1982), Gurtu (1985), Mahajan (1990), Srivastav (1991), Davison (1992), T. Mohanan (1994), Dwivedi (1994), Butt (1995), Dayal (1996), Lidz, (1997), Rakesh Bhatt (1999) and Kidwai (2000) took on the challenge posed by “exotic language” phenomena to linguistic theory, refining our understanding of the nature of Universal Grammar and simultaneously making accessible to the general linguistic audience special properties of the languages of South Asia. -

Information-Theoretic Causal Inference of Lexical Flow

Information-theoretic causal inference of lexical flow Johannes Dellert language Language Variation 4 science press Language Variation Editors: John Nerbonne, Martijn Wieling In this series: 1. Côté, Marie-Hélène, Remco Knooihuizen and John Nerbonne (eds.). The future of dialects. 2. Schäfer, Lea. Sprachliche Imitation: Jiddisch in der deutschsprachigen Literatur (18.–20. Jahrhundert). 3. Juskan, Martin. Sound change, priming, salience: Producing and perceiving variation in Liverpool English. 4. Dellert, Johannes. Information-theoretic causal inference of lexical flow. ISSN: 2366-7818 Information-theoretic causal inference of lexical flow Johannes Dellert language science press Dellert, Johannes. 2019. Information-theoretic causal inference of lexical flow (Language Variation 4). Berlin: Language Science Press. This title can be downloaded at: http://langsci-press.org/catalog/book/233 © 2019, Johannes Dellert Published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence (CC BY 4.0): http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISBN: 978-3-96110-143-6 (Digital) 978-3-96110-144-3 (Hardcover) ISSN: 2366-7818 DOI:10.5281/zenodo.3247415 Source code available from www.github.com/langsci/233 Collaborative reading: paperhive.org/documents/remote?type=langsci&id=233 Cover and concept of design: Ulrike Harbort Typesetting: Johannes Dellert Proofreading: Amir Ghorbanpour, Aniefon Daniel, Barend Beekhuizen, David Lukeš, Gereon Kaiping, Jeroen van de Weijer, Fonts: Linux Libertine, Libertinus Math, Arimo, DejaVu Sans Mono Typesetting software:Ǝ X LATEX Language Science Press Unter den Linden 6 10099 Berlin, Germany langsci-press.org Storage and cataloguing done by FU Berlin Contents Preface vii Acknowledgments xi 1 Introduction 1 2 Foundations: Historical linguistics 7 2.1 Language relationship and family trees ............. -

Information-Theoretic Causal Inference of Lexical Flow

Information-theoretic causal inference of lexical flow Johannes Dellert language Language Variation 4 science press Language Variation Editors: John Nerbonne, Martijn Wieling In this series: 1. Côté, Marie-Hélène, Remco Knooihuizen and John Nerbonne (eds.). The future of dialects. 2. Schäfer, Lea. Sprachliche Imitation: Jiddisch in der deutschsprachigen Literatur (18.–20. Jahrhundert). 3. Juskan, Martin. Sound change, priming, salience: Producing and perceiving variation in Liverpool English. 4. Dellert, Johannes. Information-theoretic causal inference of lexical flow. ISSN: 2366-7818 Information-theoretic causal inference of lexical flow Johannes Dellert language science press Dellert, Johannes. 2019. Information-theoretic causal inference of lexical flow (Language Variation 4). Berlin: Language Science Press. This title can be downloaded at: http://langsci-press.org/catalog/book/233 © 2019, Johannes Dellert Published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence (CC BY 4.0): http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISBN: 978-3-96110-143-6 (Digital) 978-3-96110-144-3 (Hardcover) ISSN: 2366-7818 DOI:10.5281/zenodo.3247415 Source code available from www.github.com/langsci/233 Collaborative reading: paperhive.org/documents/remote?type=langsci&id=233 Cover and concept of design: Ulrike Harbort Typesetting: Johannes Dellert Proofreading: Amir Ghorbanpour, Aniefon Daniel, Barend Beekhuizen, David Lukeš, Gereon Kaiping, Jeroen van de Weijer, Fonts: Linux Libertine, Libertinus Math, Arimo, DejaVu Sans Mono Typesetting software:Ǝ X LATEX Language Science Press Unter den Linden 6 10099 Berlin, Germany langsci-press.org Storage and cataloguing done by FU Berlin Contents Preface vii Acknowledgments xi 1 Introduction 1 2 Foundations: Historical linguistics 7 2.1 Language relationship and family trees ............. -

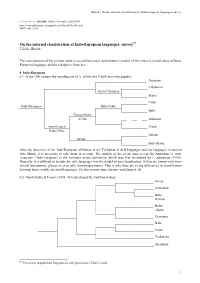

Blažek : on the Internal Classification of Indo-European Languages: Survey

Blažek : On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey Linguistica ONLINE. Added: November 22nd 2005. http://www.phil.muni.cz/linguistica/art/blazek/bla-003.pdf ISSN 1801-5336 On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey[*] Václav Blažek The main purpose of the present study is to confront most representative models of the internal classification of Indo- European languages and their daughter branches. 0. Indo-European 0.1. In the 19th century the tree-diagram of A. Schleicher (1860) was very popular: Germanic Lithuanian Slavo-Lithuaian Slavic Celtic Indo-European Italo-Celtic Italic Graeco-Italo- -Celtic Albanian Aryo-Graeco- Greek Italo-Celtic Iranian Aryan Indo-Aryan After the discovery of the Indo-European affiliation of the Tocharian A & B languages and the languages of ancient Asia Minor, it is necessary to take them in account. The models of the recent time accept the Anatolian vs. non- Anatolian (‘Indo-European’ in the narrower sense) dichotomy, which was first formulated by E. Sturtevant (1942). Naturally, it is difficult to include the relic languages into the model of any classification, if they are known only from several inscriptions, glosses or even only from proper names. That is why there are so big differences in classification between these scantily recorded languages. For this reason some scholars omit them at all. 0.2. Gamkrelidze & Ivanov (1984, 415) developed the traditional ideas: Greek Armenian Indo- Iranian Balto- -Slavic Germanic Italic Celtic Tocharian Anatolian [*] Previously unpublished. Reproduced with permission. [Editor’s note] 1 Blažek : On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey 0.3.