Brothers in Arms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Bulletin Volume 30 No

American Association of Teachers of French NATIONAL BULLETIN VOLUME 30 NO. 1 SEPTEMBER 2004 FROM THE PRESIDENT butions in making this an exemplary con- utility, Vice-President Robert “Tennessee ference. Whether you were in attendance Bob” Peckham has begun to develop a Web physically or vicariously, you can be proud site in response to SOS calls this spring of how our association represented all of and summer from members in New York us and presented American teachers of state, and these serve as models for our French as welcoming hosts to a world of national campaign to reach every state. T- French teachers. Bob is asking each chapter to identify to the Regional Representative an advocacy re- Advocacy, Recruitment, and Leadership source person to work on this project (see Development page 5), since every French program is sup- Before the inaugural session of the con- ported or lost at the local level (see pages 5 ference took center stage, AATF Executive and 7). Council members met to discuss future A second initiative, recruitment of new initiatives of our organization as we strive to members, is linked to a mentoring program respond effectively to the challenges facing to provide support for French teachers, new Atlanta, Host to the Francophone World our profession. We recognize that as teach- teachers, solitary teachers, or teachers ers, we must be as resourceful outside of We were 1100 participants with speak- looking to collaborate. It has been recog- the classroom as we are in the classroom. nized that mentoring is essential if teach- ers representing 118 nations, united in our We want our students to become more pro- passion for the French language in its di- ers are to feel successful and remain in the ficient in the use of French and more knowl- profession. -

Comrades Come Rally!

Comrades Come Rally! A tremendously evocative, emotional but also uplifting evening was enjoyed by over 80 comrades who rallied to the call to celebrate brigaders from the UK and Ireland who fought to defend democracy in Spain during the Spanish Civil War. Housed in the Holywell Music Room, Oxford, the first purpose built 18 th Century concert hall in Europe, professional actors Alison Skilbeck, Time Hardy and jeff Robert, held the audience spell bound with their renditions of brigaders’ poems, correspondence and memoirs of their battles and the heroism of their comrades. Interspersed between readings from Cecil Day Lewis, John Cornford, Charlotte Haldane, Frank McCasker, John Dunlop, Thora Silverthorne, Kenneth Sinclair- Loutit, Jason Gurney, Rev. Robert Hilliard, Gilbert Taylor, Jack Jones, Nan Green, Jim Brewer and Bob Cooney, were music and songs by Na Mara with “The Bite”, “Only for Three Months” and “The English Penny”; “La Carmagnole” and “The Minstrel Boy” by Brenda O’Riordan; “Song for Charlie Donnelly” and “If My Voice On Earth Should Die” by Manus O’Riordan – with both singing “Viva la Quinta Brigada” and a medley based on the flamenco palos of seguiriyas, tangos, taranta and rumba by Marcos, professional flamenco guitarist. The audience gave full vent to their sympathy in singing “The Valley of Jarama” led by Na Mara before the interval and the evening concluded with la Pasionaria’s iconic farewell speech to the International Brigades, read initially in Spanish by Alison, but reading the whole speech in English. Finally, all joined in with a rousing rendition of “The Internationale”. Marlene Sideway, President of the IBMT, thanked the Oxford IB memorial Committee for organizing the fundraiser on behalf of the IBMT. -

Anarchists in the Late 1990S, Was Varied, Imaginative and Often Very Angry

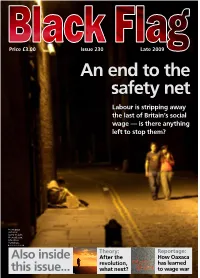

Price £3.00 Issue 230 Late 2009 An end to the safety net Labour is stripping away the last of Britain’s social wage — is there anything left to stop them? Front page pictures: Garry Knight, Photos8.com, Libertinus Yomango, Theory: Reportage: Also inside After the How Oaxaca revolution, has learned this issue... what next? to wage war Editorial Welcome to issue 230 of Black Flag, the fifth published by the current Editorial Collective. Since our re-launch in October 2007 feedback has generally tended to be positive. Black Flag continues to be published twice a year, and we are still aiming to become quarterly. However, this is easier said than done as we are a small group. So at this juncture, we make our usual appeal for articles, more bodies to get physically involved, and yes, financial donations would be more than welcome! This issue also coincides with the 25th anniversary of the Anarchist Bookfair – arguably the longest running and largest in the world? It is certainly the biggest date in the UK anarchist calendar. To celebrate the event we have included an article written by organisers past and present, which it is hoped will form the kernel of a general history of the event from its beginnings in the Autonomy Club. Well done and thank you to all those who have made this event possible over the years, we all have Walk this way: The Black Flag ladybird finds it can be hard going to balance trying many fond memories. to organise while keeping yourself safe – but it’s worth it. -

Merchant City Women's

Glasgow Merchant City Women’s Heritage Walk Glasgow Merchant City Women’s Heritage Walk A portrait hangs in Glasgow’s People’s Palace. Infamous as damning evidence of the city’s role in the transatlantic slave trade, the Glassford Family portrait holds another secret. The face of the wealthy merchant’s wife has been painted over that of his former spouse. This piece of 18th century editing deems women to be replaceable, almost ghostly: there in spirit, but not important to the story. This map aims to redress that view and to shout about, share and celebrate the achievements of women in this regenerated and thriving quarter of Glasgow. Women have played a part in this area from its dear green beginnings, through its darker days, to its recent resurgence. So, join us on a journey of her-stories - you can choose to follow the suggested route of the walk (in which case allow this to take around 45 minutes to an hour) or, if you have time, why not take a little longer to wander and soak up the sights and sounds of the area? Route map ROTTENROW Queen St Train Station N PORTLAND ST site of Rottenrow Hospital GEORGE ST RICHMOND ST George Square site of GEORGE ST Strickland Press COCHRANE ST MONTROSE ST Herald Building QUEEN ST site of Ramshorn Church Women’s INGRAM ST & Graveyard Centre ALBION ST INGRAM ST MILLER ST WILSON ST City BRUNSWICK ST Halls CANDLERIGGS HIGH ST WALLS ST BELL ST ARGYLE STVIRGINIA ST GLASSFORD ST HUTCHESON ST TRONGATE CANDLERIGGS ALBION ST Panopticon former GWL HIGH ST premises PARNIE ST TRONGATE STOCKWELL ST Mercat Cross ET’S BEGIN our tour by walking to the (1884–1971) and Ethel Macdonald (1909–1960) upper edges of the Merchant City. -

This Mess We're In

scottishleftreviewIssue 55 November/December 2009 £2.00 This mess we’re in... scottishleftreviewIssue 55 November/December 2009 Contents Comment ........................................................2 Us swallowing their medicine ......................14 Root of this evil ...............................................6 Robin McAlpine Neil Davidson Fragments of truth .......................................16 Mark Hirst Work isn’t working ............................................8 Lessons for now ............................................18 Isobel Lindsay Bob Thomson Why we fight ..................................................10 Minimum isn’t enough ..................................20 Alan McKinnon Peter Kelly No such thing as failure ................................12 The English postman ....................................22 John Barker Tom Nairn stance (which is hard to argue with, other than that it appears to assume that the speculative bit is a necessary evil). There Comment is also the active state intervention approach which suggests t would be understandable if the regular Scottish Left Review that the retail banking bit should in fact be nationalised and Ireader gave a slight sign of resignation at the thought of yet run as a secure public service. And then there are those who another ‘what is to be done?’ issue. It’s not just that we’ve run a want to address some of the root causes of the whole thing few articles on the theme of ‘reforming the post-banking crash by tackling the way speculative financial capitalism works in world’. It’s not even that there have been enough column inches the first place (such as advocates of a Tobin Tax). What do we on the subject from which to build an airport rail link. It’s that you learn from all of this? Well, the majority of these proposals do may well feel that the totality of the suggestions you have heard not really appear to envisage a global financial system which and read in the last year may sound a little bit underwhelming. -

There's a Valley in Spain Called Jarama

There's a valley in Spain called Jarama The development of the commemoration of the British volunteers of the International Brigades and its influences D.G. Tuik Studentno. 1165704 Oudendijk 7 2641 MK Pijnacker Tel.: 015-3698897 / 06-53888115 Email: [email protected] MA Thesis Specialization: Political Culture and National Identities Leiden University ECTS: 30 Supervisor: Dhr Dr. B.S. v.d. Steen 27-06-2016 Image frontpage: photograph taken by South African photographer Vera Elkan, showing four British volunteers of the International Brigades in front of their 'camp', possibly near Albacete. Imperial War Museums, London, Collection Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. 1 Contents Introduction : 3 Chapter One – The Spanish Civil War : 11 1.1. Historical background – The International Brigades : 12 1.2. Historical background – The British volunteers : 14 1.3. Remembering during the Spanish Civil War : 20 1.3.1. Personal accounts : 20 1.3.2. Monuments and memorial services : 25 1.4. Conclusion : 26 Chapter Two – The Second World War, Cold War and Détente : 28 2.1. Historical background – The Second World War : 29 2.2. Historical background – From Cold War to détente : 32 2.3. Remembering between 1939 and 1975 : 36 2.3.1. Personal accounts : 36 2.3.2. Monuments and memorial services : 40 2.4. Conclusion : 41 Chapter Three – Commemoration after Franco : 43 3.1. Historical background – Spain and its path to democracy : 45 3.1.1. The position of the International Brigades in Spain : 46 3.2. Historical background – Developments in Britain : 48 3.2.1. Decline of the Communist Party of Great Britain : 49 3.2.2. -

Anarch Fortnightly 131‘ Augzzst, 1 98.! Vol 42, No 15:7

anarch fortnightly 131‘ Augzzst, 1 98.! Vol 42, No 15:7 _ OK ER 160 years ago now, Black -an Dwarf, in a pers'pica.cious inissive to his friend the Yellow Bonze. ren1arl~;e cl that. "in England, the great art is not to avoid tyranny, but to disguise it"."i"""‘“ The wave of riots across Britain this nionth, however, bearing in their walte serious threats about the hitroduction of rubber bullets. water cannon, even taiiltsz the re- instatement of the Riot act and the t;'.5i&l)llSl1I11€I‘rI oi special riot courts arid arniy camps for convicted riot- ers and ioote rs, shows just how poor that disguise really is. l\.»-'largare: Thatcher admitted as much when she said "The veneer of civilisation is very thin. It has to be cherished if it is to continue.Whateve r Marg- aret Thatcher actually n1ea.ns, it is certain that she was ft-3l?£3I’I‘ll1.§?",' to a certain scale of values guaranteed by the police - or at least that large section of them who subscribe to the views of the chief constable of Man- chester, James Anderton. These have predictably adopted the attitude that the riots were not caused by any social factor, but militarily organ- ised by masked guerrillas on motor bike s, with London accents and CB radios. This is l~;nown as the cons- piracy theory, or what Je re my Bentham once described as the ‘Hobgoblin Argument’ - i.e. using the claim that we are ‘close to anarchy‘ in order to sit tight and do nothing. -

Anarchism in Siberia Prison Gates

Number 52 50 pence or one dollar October 2007 Prison Gates The gates of the Modelo Prison in Barcelona were set workers from the Calcetería Hispania Tapices, Vidal y alight during a prison riot and put out of commission. Vda de Enrique Escapa firm are CNT personnel. So not The Barcelona Woodworkers’ Union imposed a an inch! (...) And the affiliation of the comrades on strike boycott on repair work. Faced with the impossibility of at Frau Brothers? CNT. So, not an inch!” (Cultura having repairs done there, the authorities decided to Obrera, 21 November 1931) ship the gates out to Majorca. Soldiers loaded the gates On 17 October Cultura Obrera saw fit to denounce on board the ship for delivery as the Barcelona dockers Rafael Mercadal, the president of the UGT•affiliated refused to do so. “Desarrollo y Arte” association as an active participant In September 1931 the gates arrived in Palma but the in the repair job on the gates. Is this, it asked, what the dockworkers there, most of them CNT personnel like UGT is all about … strike•breaking? However, Rafael their colleagues on the mainland, refused to unload them. Mercader was a familiar name to the anarcho• The scene in Barcelona was replayed: troops from the syndicalists; he had settled in Palma but came from a nearby garrison had to unload the gates under Civil nearby town, moving after breaking a strike at the Can Guard protection. Pieras plant. When socialist councillors Miguel Bisbal The Balearic Islands CNT Woodworkers’ Union (son of Llorenç Bisbal, the ‘founding father’ of socialism imposed a boycott and asked workers to refuse to do the on the island) and Miguel Porcel acted in favour of the repair work as an act of solidarity. -

288381679.Pdf

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Loughborough University Institutional Repository This item was submitted to Loughborough University as a PhD thesis by the author and is made available in the Institutional Repository (https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/) under the following Creative Commons Licence conditions. For the full text of this licence, please go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ Towards a Libertarian Communism: A Conceptual History of the Intersections between Anarchisms and Marxisms By Saku Pinta Loughborough University Submitted to the Department of Politics, History and International Relations in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Approximate word count: 102 000 1. CERTIFICATE OF ORIGINALITY This is to certify that I am responsible for the work submitted in this thesis, that the original work is my own except as specified in acknowledgments or in footnotes, and that neither the thesis nor the original work contained therein has been submitted to this or any other institution for a degree. ……………………………………………. ( Signed ) ……………………………………………. ( Date) 2 2. Thesis Access Form Copy No …………...……………………. Location ………………………………………………….……………...… Author …………...………………………………………………………………………………………………..……. Title …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Status of access OPEN / RESTRICTED / CONFIDENTIAL Moratorium Period :…………………………………years, ending…………../…………20………………………. Conditions of access approved by (CAPITALS):…………………………………………………………………… Supervisor (Signature)………………………………………………...…………………………………... Department of ……………………………………………………………………...………………………………… Author's Declaration : I agree the following conditions: Open access work shall be made available (in the University and externally) and reproduced as necessary at the discretion of the University Librarian or Head of Department. It may also be digitised by the British Library and made freely available on the Internet to registered users of the EThOS service subject to the EThOS supply agreements. -

Anarchists in the Gulag, Prison and Exile Special Double Issue Trouble in Moscow the Club Is Now Moving to the New Quarters, While Couldn’T Ask Anybody Either

Number 55•56 one pound or two dollars Oct. 2008 Trouble in Moscow: From the life of the “Liesma” [“Flame”] Group [This account covers the Latvian anarchists’ activities from its prescribed path and topple the theory laid out in in Moscow, up to the Cheka raids of April 1918, when the thick volumes of Marx’s Capital. the Bolsheviks attacked anarchists in the city in the All this made comrades think that there was no time name of “Law and Order”] to wait until capital would “concentrate” in their cash The group was founded in August 1917 and from box in order to rent quarters; quarters had to be the beginning worked in the syndicalist direction. acquired now, in the nearest future, irrespective of how Before its foundation comrades worked independ• and by what means. As social expropriations were ently, as well as together with existing Russian groups. already happening in other cities, where private houses, Later, in view of much greater efficiency if comrades shops, factories and other private property were being could communicate in Latvian, working with Latvian nationalised, our comrades considered this a justified workers, comrades decided to unite in a permanent and important step in continuing the revolution, and group and found quarters which could be open at any decided to look out for an appropriate building where time to interested workers, where existing anarchist we could start our club. literature would be available for their use, where on In the end such a house was found in Presnensk certain days comrades would be able to come together, Pereulok number 3. -

Freedom to Speak? Social Centre

www.freedoinpress-org.uk LO FEBRUARY 2007 Favela Rising review Svartfrosk column p a g e ^ ~ ; page 7 '. page 8 WSF: NOT FOR THE POOR I be 2® 07f^rld Social FotUin |^ v#e;hUmah^^b^^Crneq:^gediCr^fi hea^dattcism fbf pursue their thinking; its-most recent financial pluming, democratieal^ which denied access; to the poor., The Seeretidtobf® ■- p fifk ^ o xeffective adtion4;^M yearwasheld mKQSya, has been Thei^F'beg^ thisy^Dhychs^ charged widih^^^% 'bym edia ^%^ti^^toindividu Aftica fo groupsin. jhe attend'theget^dgether'wto ^in^e^\%ejy;e?q^^ International food while shhufeato jSfbS^nrte. ’. h efty e b jp ^ Theid®pbf%^ the , A rouhd ^ the;eyei% whj^ the the r^|id)lal;m ini^ Saxemmt and the teemational ; ISOrmemtoTib^^ c b n tin n i^ ^ guidelines. The which has;am0^ b f e e f • members national Tmdes^Jmon C ouncils, though ‘this was-sbmeV^hat mitigated groups, efeectivd^^t^'as thenucleus f^lftdneyrfeom the Italian government, orgamsau^-otme wdfld Social Forums takes place. Which anarchirt^oups^cOndeinned^'m Thegrowthof thelntemational COBJXC&^fa^ and a rte^dvdeal with- for tife ;toM Tortmis has Come alongside increasing^^conoerns^3c^tib.e K enp^y^d|^;had been threaten.^; accountability and-dkeption o fffae ^ e n tt tiaemselVe^mkl tife turnout this I k year is the lowest since the 'Social a n ti-to d iu s t m '^sures and .mCisjm in Locals turn out in force to support the occupation of the Vortex Social Centre in Stoke Newington, ForumsbegaiL theCbmpan^^hich, itwasalleged, m m . -

Inside: an Antifascist's Memories of Internment; Book Reviews

Number 49 50 pence or one dollar Jan. 2007 John Taylor Caldwell 1911•2007 With the death of John Taylor Caldwell aged 95 we have lost continued to be published until, in 1962, the Press was forced the last significant link with an anarchist anti•parliamentary to remove to Montrose Street. The George Street premises form of socialism/communism which flourished in the first were the heart of this anarchist oasis in Glasgow, as a few decades of the last century, and was part of a tradition of meeting•place, bookshop, printing press and social centre for libertarian socialism going back to the days of William a whole generation of Glaswegians. John managed to capture Morris and the Socialist League – a socialism based on this in an epitaph for the group’s old HQ written after it had working•class self•activity manifest in workers’ councils and been bulldozed for a new University of Strathclyde building: direct action rather than in reliance on political parties, When the meeting was over the chairs were replaced and whether social democratic or revolutionary. the audience meandered upstairs where books were bought This kind of anarchism is assumed to have become and fresh arguments broke out amongst small groups. The extinct during the inter•War period, crushed between the old man was tired… but he was loth to hurry them away. pincers of the Parliamentary Labour Party and the Commu• Some, he knew, went home to misery and loneliness. The nist Party. But in a few places, notably Glasgow, it continued evening in the old cellar was a rare feast of companionship to flourish, thanks to individuals like John and his mentor, for them.