Brothers in Arms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anarchists in the Late 1990S, Was Varied, Imaginative and Often Very Angry

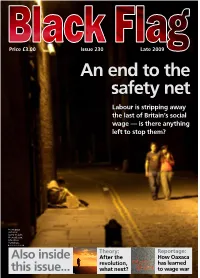

Price £3.00 Issue 230 Late 2009 An end to the safety net Labour is stripping away the last of Britain’s social wage — is there anything left to stop them? Front page pictures: Garry Knight, Photos8.com, Libertinus Yomango, Theory: Reportage: Also inside After the How Oaxaca revolution, has learned this issue... what next? to wage war Editorial Welcome to issue 230 of Black Flag, the fifth published by the current Editorial Collective. Since our re-launch in October 2007 feedback has generally tended to be positive. Black Flag continues to be published twice a year, and we are still aiming to become quarterly. However, this is easier said than done as we are a small group. So at this juncture, we make our usual appeal for articles, more bodies to get physically involved, and yes, financial donations would be more than welcome! This issue also coincides with the 25th anniversary of the Anarchist Bookfair – arguably the longest running and largest in the world? It is certainly the biggest date in the UK anarchist calendar. To celebrate the event we have included an article written by organisers past and present, which it is hoped will form the kernel of a general history of the event from its beginnings in the Autonomy Club. Well done and thank you to all those who have made this event possible over the years, we all have Walk this way: The Black Flag ladybird finds it can be hard going to balance trying many fond memories. to organise while keeping yourself safe – but it’s worth it. -

This Mess We're In

scottishleftreviewIssue 55 November/December 2009 £2.00 This mess we’re in... scottishleftreviewIssue 55 November/December 2009 Contents Comment ........................................................2 Us swallowing their medicine ......................14 Root of this evil ...............................................6 Robin McAlpine Neil Davidson Fragments of truth .......................................16 Mark Hirst Work isn’t working ............................................8 Lessons for now ............................................18 Isobel Lindsay Bob Thomson Why we fight ..................................................10 Minimum isn’t enough ..................................20 Alan McKinnon Peter Kelly No such thing as failure ................................12 The English postman ....................................22 John Barker Tom Nairn stance (which is hard to argue with, other than that it appears to assume that the speculative bit is a necessary evil). There Comment is also the active state intervention approach which suggests t would be understandable if the regular Scottish Left Review that the retail banking bit should in fact be nationalised and Ireader gave a slight sign of resignation at the thought of yet run as a secure public service. And then there are those who another ‘what is to be done?’ issue. It’s not just that we’ve run a want to address some of the root causes of the whole thing few articles on the theme of ‘reforming the post-banking crash by tackling the way speculative financial capitalism works in world’. It’s not even that there have been enough column inches the first place (such as advocates of a Tobin Tax). What do we on the subject from which to build an airport rail link. It’s that you learn from all of this? Well, the majority of these proposals do may well feel that the totality of the suggestions you have heard not really appear to envisage a global financial system which and read in the last year may sound a little bit underwhelming. -

Anarch Fortnightly 131‘ Augzzst, 1 98.! Vol 42, No 15:7

anarch fortnightly 131‘ Augzzst, 1 98.! Vol 42, No 15:7 _ OK ER 160 years ago now, Black -an Dwarf, in a pers'pica.cious inissive to his friend the Yellow Bonze. ren1arl~;e cl that. "in England, the great art is not to avoid tyranny, but to disguise it"."i"""‘“ The wave of riots across Britain this nionth, however, bearing in their walte serious threats about the hitroduction of rubber bullets. water cannon, even taiiltsz the re- instatement of the Riot act and the t;'.5i&l)llSl1I11€I‘rI oi special riot courts arid arniy camps for convicted riot- ers and ioote rs, shows just how poor that disguise really is. l\.»-'largare: Thatcher admitted as much when she said "The veneer of civilisation is very thin. It has to be cherished if it is to continue.Whateve r Marg- aret Thatcher actually n1ea.ns, it is certain that she was ft-3l?£3I’I‘ll1.§?",' to a certain scale of values guaranteed by the police - or at least that large section of them who subscribe to the views of the chief constable of Man- chester, James Anderton. These have predictably adopted the attitude that the riots were not caused by any social factor, but militarily organ- ised by masked guerrillas on motor bike s, with London accents and CB radios. This is l~;nown as the cons- piracy theory, or what Je re my Bentham once described as the ‘Hobgoblin Argument’ - i.e. using the claim that we are ‘close to anarchy‘ in order to sit tight and do nothing. -

Inside: an Antifascist's Memories of Internment; Book Reviews

Number 49 50 pence or one dollar Jan. 2007 John Taylor Caldwell 1911•2007 With the death of John Taylor Caldwell aged 95 we have lost continued to be published until, in 1962, the Press was forced the last significant link with an anarchist anti•parliamentary to remove to Montrose Street. The George Street premises form of socialism/communism which flourished in the first were the heart of this anarchist oasis in Glasgow, as a few decades of the last century, and was part of a tradition of meeting•place, bookshop, printing press and social centre for libertarian socialism going back to the days of William a whole generation of Glaswegians. John managed to capture Morris and the Socialist League – a socialism based on this in an epitaph for the group’s old HQ written after it had working•class self•activity manifest in workers’ councils and been bulldozed for a new University of Strathclyde building: direct action rather than in reliance on political parties, When the meeting was over the chairs were replaced and whether social democratic or revolutionary. the audience meandered upstairs where books were bought This kind of anarchism is assumed to have become and fresh arguments broke out amongst small groups. The extinct during the inter•War period, crushed between the old man was tired… but he was loth to hurry them away. pincers of the Parliamentary Labour Party and the Commu• Some, he knew, went home to misery and loneliness. The nist Party. But in a few places, notably Glasgow, it continued evening in the old cellar was a rare feast of companionship to flourish, thanks to individuals like John and his mentor, for them. -

Brothers in Arms

The Anarchist Library (Mirror) Anti-Copyright Brothers in Arms Stuart Christie 2009 WRITING IN the preface to l’Espagne Libre, in 1946, the year of my birth, Albert Camus said of the Spanish struggle: “It is now nine years that men of my generation have had Spain within their hearts. Nine years that they have carried it with them like an evil wound. It was in Spain that men learned that one can be right and yet be beaten, that force can vanquish spirit, that there are times when courage is not its own recompense. It is this, doubt- less, which explains why so many men, the world over, regard the Spanish drama as a personal tragedy”. Stuart Christie On 1 April 2009 seventy years will have passed since General Brothers in Arms Franco declared victory in his three-year crusade against the Span- 2009 ish Republic. His victory was won with the military support of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, the moral support of the Roman Retrieved on 22nd September 2020 from Catholic Church and the covert diplomatic connivance of Britain https://libcom.org/history/brothers-arms and France, the prime movers in the Non-Intervention Agreement. Article by Stuart Christie in Scottish Review of Books, Volume 5, It brought not peace but the outbreak of a vengeful and prolonged Issue 1, 2009 forty-year war of vindictive terror, humiliation and suffering for the losers, the Spanish people. Apart from the victims of the war it- usa.anarchistlibraries.net self, between 1939 and 1951 at least 50,000 Spaniards paid with their lives for their support of the Republic while hundreds of thousands paid with their freedom. -

Anarchism in Glasgow (Interview)

Anarchist library Anti-Copyright Anarchism in Glasgow (Interview) Various Authors 14/8/87 In August 1987 the Raesides, who had been living in Australia for many years, returned to Glasgow for a visit. This provided a rare op- portunity to bring together some surviving members of anarchist groups in Glasgow during the 1940s for a public discussion on the history of that movement and the lesson which can be learned. Q: How did people come in contact with the movement and Various Authors how did the movement strike them at the time? Anarchism in Glasgow (Interview) JR: Well, the clothes have changed a bit! And the venue 14/8/87 — the anarchist movement would have had to grow Anarchy is Order CD quite a bit to get a room like this. Transcribed in November 1993 from a not-always-clear cassette MB: Yes… The “Hangman’s Rest”: when there wasa tape. A formerly inaudible section has now been transcribed with lull in the questions the rats used to come out‼ help from Charlie Baird Jnr. JR: Or street corners… en.anarchistlibraries.net JTC: The movement started in Glasgow in a way that’s buried in a certain amount of mystery because they haven’t been able to research it properly, but after the Paris Commune a number of Frenchmen came to Britain and one of these settled in Glasgow and be- came the companion of a woman called MacDonald who lived in Crown St. She had anarchist views and they organised the first anarchism movement in Glas- gow working from Crown St. -

Towards a Cosmopolitan Account of Jewish Socialism Class, Identity and Immigration in Edwardian London Ben Gidley

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Birkbeck Institutional Research Online Towards a Cosmopolitan Account of Jewish Socialism Class, Identity and Immigration in Edwardian London Ben Gidley This article reflects on the historiography of Jewish socialism in Britain by arguing that we cannot understand it without attending fully to both its local context and its transnational and specifically Jewish context. Although the article focuses on Edwardian Britain, the argument speaks equally to other times and places, and indeed for other comparable non-Jewish diasporic radicalisms. In anchoring my argument in Edwardian Britain, I will try to show that the particularities of British socialist intellectual culture, as well as the wider social, cultural and political context in which socialism developed here then, gave a particular shape and form to the varieties of socialism which flourished among Jewish immigrants in London, Leeds, Manchester, Glasgow, Dublin and other cities û but also that the particular cultural traditions and transnational networks in the (mainly Yiddish-speaking) Ashkenazi Jewish world gave them a particular content. The historiography of Jewish socialism in Britain There is a rich historiography of immigrant socialism and of working class Jews in Britain. This includes an earlier Yiddish-language historiography,1 as well as a body of work emerging after the turn in the 1970s to a ‘history from below perspective’, which foregrounded previously neglected dimen- sions of the migrant experience and in particular the dimension of class.2 There is also an important body of socialist history that has touched on the experiences of Jewish activists.3 However, much of this literature attends only to one of the two primary contexts, the national or the Jewish. -

Discover NLS the Autumn Issue of Discover NLS Celebrates the Official Opening of Our New Visitor Centre in the George IV Bridge Building

THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR and Scotland’s tireless activists The magazine of the National Library of Scotland | www.nls.uk | Issue 13 Autumn 2009 The origin of Darwin’s greatest work TOP 10 SCOttish Scientists PLUS Conan Doyle and the Afghan connection WELCOME A new Visitor Centre and a new issue of Discover NLS The autumn issue of Discover NLS celebrates the official opening of our new Visitor Centre in the George IV Bridge building. After many T It’s a tale months of work the new facilities opened over the summer to very positive feedback from staff and of women customers. We hope you will have an opportunity to enjoy turning into the new shop and café area, and the general feeling of campaigners, DISCOVER NLS IssUE 13 AUTUMN 2009 welcome that the new facilities have given to the Library. sometimes for CONTACT US Also in this issue of Discover NLS, Daniel Gray has written the first time We welcome all comments, questions, submissions a fascinating piece on the role that Scotswomen played in and subscription enquiries. the Spanish Civil War. It’s a tale of women turning into Please write to us at the National Library of Scotland campaigners, sometimes for the first time in their lives. address below or email [email protected] Elsewhere, we explore a series of links found in the Library’s collections that bring together Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the FOR NLS EDITOR-IN-CHIEF publisher William Blackwood and Sons and Afghanistan. Alexandra Miller MANAGING EDITOR Touching on connections, Conan Doyle was born in 1859, Julian Stone which also happens to be the year that John Murray first Director of DEVELOPment AND EXTERNAL RELATIONS published Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. -

Anarchism in 1940S Glasgow

Anarchism in 1940s Glasgow Two interviews with veterans of the anarchist scene in 1940s Glasgow. Source; Research on Anarchism http://raforum.info/ ========= 1) Charlie Baird Sr. : An Interview 6th June 1977 Before the war I’d been sympathetic to the Communist Party, as early as 16 or 17 years of age. It wasn’t until the war, when Russia had signed the pact with Hitler, that I started to have my doubts about the CP. But even prior to that I’d drifted away from them. When the war started, I took up the Conscientious Objector position, and finished up, of course, in jail. It was in jail - I hadn’t been conscious that there was such a movement as the libertarian movement, the anarchist movement - I thought that the CP was the last thing in left-wing movements. I met two lads in prison (I also knew one prior to going in, who’d told me to look out for these two lads) ; one was Jimmy Dick. He’d managed to get some anarchist literature in. I went through that and discovered that was what I’d been looking for. It was what I’d believed, even when I was in the CP ; I was dissatisfied with the centralised character of the movement. Then, of course, when we came out, there was an anarchist movement in Glasgow at that particular time. We came out of jail and teamed up with them. It was around 1942 when I came out of jail,and there were about 40 active members of the group. -

Papers of Patricia Lynch and R. M. Fox

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 79 PAPERS OF PATRICIA LYNCH AND R. M. FOX (MSS 34,923-34,931; 40,248-40,419) (Accession No. 4937) Patricia Lynch (1898-1972) was the author of children’s stories mostly set in Ireland; her husband, R.M. (Richard Michael) Fox (1891-1969), was an historian, journalist, and socialist. Compiled by Margaret Burke Contents Introduction 8 I Papers of Patricia Lynch 10 I.i Literary works 10 I.i.1 Novels 10 I.i.1.A The Green Dragon (1925) 10 I.i.1.B The Cobbler’s Apprentice (1930) 10 I.i.1.C The Turf-cutter’s Donkey (1934) 10 I.i.1.D The Turf-cutter’s Donkey Goes Visiting (1935) 11 I.i.1.E The King of the Tinkers (1938) 11 I.i.1.F The Turf-cutter’s Donkey Kicks Up His Heels (1939) 11 I.i.1.G The Grey Goose of Kilnevin (1939) 11 I.i.1.H Fiddler’s Quest (1941) 12 I.i.1.I Long Ears (1943) 12 I.i.1.J Brogeen of the Stepping Stones (1947) 12 I.i.1.K The Mad O’Haras (1948) 12 I.i.1.L The Dark Sailor of Youghal (1951) 13 I.i.1.M The Boy at the Swinging Lantern (1952) 13 I.i.1.N Brogeen Follows the Magic Tune (1952) 14 I.i.1.O Brogeen and the Green Shoes (1953) 14 I.i.1.P Delia Daly of Galloping Green (1953) 14 I.i.1.Q Brogeen and the Bronze Lizard (1954) 14 I.i.1.R Orla of Burren (1954) 14 I.i.1.S Brogeen and the Princess of Sheen (1955) 15 I.i.1.T Tinker Boy (1955) 15 I.i.1.U The Bookshop on the Quay (1956) 15 I.i.1.V Brogeen and the Lost Castle (1956) 16 I.i.1.W Fiona Leaps the Bonfire (1957) 16 I.i.1.X Brogeen and the Black Enchanter (1958) 16 I.i.1.Y The Old Black Sea -

Meydan 37 20170228 0920.Indd

Tarihteki Krizin Faturası Kadına Militarizmin Göçmen Kadınlardan s 8 Anarşist Kadınlar(3) Modası Umudun Reçelleri Krizin Faturasını Ödemeyeceğiz s 16 s 9 s 32 s 20 kendi “İnsan ancak anların adar özgür ins k ürdür” arasında özg SAYI:37 MART 2017 Kadınlar Sokaklara, Özgür Yaşamı Yaratmaya YAŞASlN 8 MART YAŞASlN ÖZGÜRLÜK 2 Meydan Gazetesi 37. sayısını, Umudun reçellerini tenef- Mart sayısını yine biz Anarşist Kadınlar füs zilini beklemeden yi- olarak hazırladık. Sadece gazetemizin sayfa- yecek çocuklarımız, onlar larında değil, meydanlarda da bu ay yine biz için “nasıl”ını tartıştığımız varız. Her yıl olduğu gibi bu yıl da 8 Mart gün- alternatif okullarımız var. Ka- demiyle buluşsak da, her gün bizim diyerek dının etine saldıran katillerin dolduracağız sokakları, meydanları. geliştirdiği katil buluşlar, par- çalanarak katledilen kadınlar, Bu sayının yazılarında öfke, tasa, heyecan, erkek ellerden akan kan var. umut, direniş var. Her birinde kadın, her bi- Büyük şehirlerin gecekondu- rinde mücadele var. Kadını hedef alan gün- larında, sınırların duvarlarında, demlerin kadının kalemiyle verdiği bir sınav akıl hastanelerinin odalarında var. Referanduma dair sözü olan, krize kaybolmuş, unutulmuş kadınlar mücadelesi alternatif olan kadın var. var. Düşmüş kadınlar var karanlı- Tarih var buram buram özgürlük ko- ğın orta yerine. Yalnız kadınlar var kan. Kolektif uyum var benleri biz Mozart’tan da öte, her şeye rağmen yapan. Dünyanın dört bir yanın- isyan şarkısını söyleyebilen. Her şeye dan sesimize ses, isyanımıza rağmen yazabilen kadınlar var ve bu ortak olan kadın yoldaşlar var. yazılarda küfre yer yok. Direnen kadın- Hiç olmasa dediğimiz bir savaş, lar var. Fabrikalarından sokaklara koşan. doğduğumuz andan itibaren et- Bitmeyen bir maratonda özgürlüğe el ele rafımızı kuşatan militarizmin be- koşan, “edi bes e” diyerek haykıran, biri denimize giydirdiği, yakıştırdığı düştüğünde diğerinin kaldırdığı kız kardeşliğin bir modası bile var. -

Scottish Anarchist We Hope Yon Will Be Truly Free in a Free World

INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Big Brother in Glasgow • Unemployed occupy Edinburgh Centre • Looking back at Timex • The Scottish Financial Mafia • Our History • and much more £1.00 NumberCAUTION1 I o MONITORED Contents 5 The Pollok Free State .................««»•••«»..»»••»»•»••.•.•"" McLlbel 2 ^ Orwell's 1984. Glasgow's 1994? » * * Hands Off Our Babies!!! .....— ...——~»— Flushing out the Scotnsh Financial Mafia —. .... 10 Ttmex- Labour and Trade Unionism at Its best 14 Spain and Its Relevance Today ................*••«....«.••••—""" 16 Anarchism In Glasgow—— ............ 20 Review: Severely Dealt With — From an Egoist Window Pane „„„™™.™...............».....»».. 24 Ireland -for a lasting peace with justice. .......... 26 Computer Networks and Anarchy ..................................... 28 London demonstration at Downing Street editorial Cover illustration; AngryArtworks into the free, we can only who do and watch them turn WELCOME TO THE FIRST ISSUE OJ struggle. We want to be but get that we nightmare of stale capitalism. We must and Scottish Anarchist We hope yon will be truly free in a free world. To the with you. Its will sing anew and write the songs of enjoy it need you! But the first step lies new world we carry in our hearts in a new Scottish Anarchist is the Journal of the your life. of tomorrow. anarchist and the SFA aim to help language . the language Scottish Federation of Anarchists (the SFA). Scottish to hope And this tomorrow? Anarchy, a free The SFA unites anarchists, libertarian us to dream again, to fight again, forums through which we society of free and equal individuals, who socialists and autonomous revolutionaries again by providing themselves from the authority talk, think and act. By organising have liberated across this fair nation.