1 Extreme Droughts and Human Responses to Them

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 the DUTCH DELTA MODEL for POLICY ANALYSIS on FLOOD RISK MANAGEMENT in the NETHERLANDS R.M. Slomp1, J.P. De Waal2, E.F.W. Ruijg

THE DUTCH DELTA MODEL FOR POLICY ANALYSIS ON FLOOD RISK MANAGEMENT IN THE NETHERLANDS R.M. Slomp1, J.P. de Waal2, E.F.W. Ruijgh2, T. Kroon1, E. Snippen2, J.S.L.J. van Alphen3 1. Ministry of Infrastructure and Environment / Rijkswaterstaat 2. Deltares 3. Staff Delta Programme Commissioner ABSTRACT The Netherlands is located in a delta where the rivers Rhine, Meuse, Scheldt and Eems drain into the North Sea. Over the centuries floods have been caused by high river discharges, storms, and ice dams. In view of the changing climate the probability of flooding is expected to increase. Moreover, as the socio- economic developments in the Netherlands lead to further growth of private and public property, the possible damage as a result of flooding is likely to increase even more. The increasing flood risk has led the government to act, even though the Netherlands has not had a major flood since 1953. An integrated policy analysis study has been launched by the government called the Dutch Delta Programme. The Delta model is the integrated and consistent set of models to support long-term analyses of the various decisions in the Delta Programme. The programme covers the Netherlands, and includes flood risk analysis and water supply studies. This means the Delta model includes models for flood risk management as well as fresh water supply. In this paper we will discuss the models for flood risk management. The issues tackled were: consistent climate change scenarios for all water systems, consistent measures over the water systems, choice of the same proxies to evaluate flood probabilities and the reduction of computation and analysis time. -

Acipenser Sturio L., 1758) in the Lower Rhine River, As Revealed by Telemetry Niels W

Outmigration Pathways of Stocked Juvenile European Sturgeon (Acipenser Sturio L., 1758) in the Lower Rhine River, as Revealed by Telemetry Niels W. P. Brevé, Hendry Vis, Bram Houben, André Breukelaar, Marie-Laure Acolas To cite this version: Niels W. P. Brevé, Hendry Vis, Bram Houben, André Breukelaar, Marie-Laure Acolas. Outmigration Pathways of Stocked Juvenile European Sturgeon (Acipenser Sturio L., 1758) in the Lower Rhine River, as Revealed by Telemetry. Journal of Applied Ichthyology, Wiley, 2019, 35 (1), pp.61-68. 10.1111/jai.13815. hal-02267361 HAL Id: hal-02267361 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02267361 Submitted on 19 Aug 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Received: 5 December 2017 | Revised: 26 April 2018 | Accepted: 17 September 2018 DOI: 10.1111/jai.13815 STURGEON PAPER Outmigration pathways of stocked juvenile European sturgeon (Acipenser sturio L., 1758) in the Lower Rhine River, as revealed by telemetry Niels W. P. Brevé1 | Hendry Vis2 | Bram Houben3 | André Breukelaar4 | Marie‐Laure Acolas5 1Koninklijke Sportvisserij Nederland, Bilthoven, Netherlands Abstract 2VisAdvies BV, Nieuwegein, Netherlands Working towards a future Rhine Sturgeon Action Plan the outmigration pathways of 3ARK Nature, Nijmegen, Netherlands stocked juvenile European sturgeon (Acipenser sturio L., 1758) were studied in the 4Rijkswaterstaat (RWS), Rotterdam, River Rhine in 2012 and 2015 using the NEDAP Trail system. -

Droughts in the Czech Lands, 1090–2012 AD Open Access Geoscientific Geoscientific Open Access 1,2 1,2 2,3 4 1,2 5 2,6 R

EGU Journal Logos (RGB) Open Access Open Access Open Access Advances in Annales Nonlinear Processes Geosciences Geophysicae in Geophysics Open Access Open Access Natural Hazards Natural Hazards and Earth System and Earth System Sciences Sciences Discussions Open Access Open Access Atmospheric Atmospheric Chemistry Chemistry and Physics and Physics Discussions Open Access Open Access Atmospheric Atmospheric Measurement Measurement Techniques Techniques Discussions Open Access Open Access Biogeosciences Biogeosciences Discussions Open Access Open Access Clim. Past, 9, 1985–2002, 2013 Climate www.clim-past.net/9/1985/2013/ Climate doi:10.5194/cp-9-1985-2013 of the Past of the Past © Author(s) 2013. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Discussions Open Access Open Access Earth System Earth System Dynamics Dynamics Discussions Droughts in the Czech Lands, 1090–2012 AD Open Access Geoscientific Geoscientific Open Access 1,2 1,2 2,3 4 1,2 5 2,6 R. Brazdil´ , P. Dobrovolny´ , M. Trnka , O. Kotyza , L. Reznˇ ´ıckovˇ a´ , H. Vala´sekˇ Instrumentation, P. Zahradn´ıcekˇ , and Instrumentation P. Stˇ epˇ anek´ 2,6 Methods and Methods and 1Institute of Geography, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic 2Global Change Research Centre AV CR,ˇ Brno, Czech Republic Data Systems Data Systems 3Institute of Agrosystems and Bioclimatology, Mendel University in Brno, Czech Republic Discussions Open Access 4 Open Access Regional Museum, Litomeˇrice,ˇ Czech Republic Geoscientific 5Moravian Land Archives, Brno, Czech Republic Geoscientific 6 Model Development Czech Hydrometeorological Institute, Brno, Czech Republic Model Development Discussions Correspondence to: R. Brazdil´ ([email protected]) Open Access Received: 29 April 2013 – Published in Clim. Past Discuss.: 8 May 2013 Open Access Revised: 4 July 2013 – Accepted: 8 July 2013 – Published: 20 August 2013 Hydrology and Hydrology and Earth System Earth System Abstract. -

The Present Status of the River Rhine with Special Emphasis on Fisheries Development

121 THE PRESENT STATUS OF THE RIVER RHINE WITH SPECIAL EMPHASIS ON FISHERIES DEVELOPMENT T. Brenner 1 A.D. Buijse2 M. Lauff3 J.F. Luquet4 E. Staub5 1 Ministry of Environment and Forestry Rheinland-Pfalz, P.O. Box 3160, D-55021 Mainz, Germany 2 Institute for Inland Water Management and Waste Water Treatment RIZA, P.O. Box 17, NL 8200 AA Lelystad, The Netherlands 3 Administrations des Eaux et Forets, Boite Postale 2513, L 1025 Luxembourg 4 Conseil Supérieur de la Peche, 23, Rue des Garennes, F 57155 Marly, France 5 Swiss Agency for the Environment, Forests and Landscape, CH 3003 Bern, Switzerland ABSTRACT The Rhine basin (1 320 km, 225 000 km2) is shared by nine countries (Switzerland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Austria, Germany, France, Luxemburg, Belgium and the Netherlands) with a population of about 54 million people and provides drinking water to 20 million of them. The Rhine is navigable from the North Sea up to Basel in Switzerland Key words: Rhine, restoration, aquatic biodiversity, fish and is one of the most important international migration waterways in the world. 122 The present status of the river Rhine Floodplains were reclaimed as early as the and groundwater protection. Possibilities for the Middle Ages and in the eighteenth and nineteenth cen- restoration of the River Rhine are limited by the multi- tury the channel of the Rhine had been subjected to purpose use of the river for shipping, hydropower, drastic changes to improve navigation as well as the drinking water and agriculture. Further recovery is discharge of water, ice and sediment. From 1945 until hampered by the numerous hydropower stations that the early 1970s water pollution due to domestic and interfere with downstream fish migration, the poor industrial wastewater increased dramatically. -

A Viking-Age Settlement in the Hinterland of Hedeby Tobias Schade

L. Holmquist, S. Kalmring & C. Hedenstierna-Jonson (eds.), New Aspects on Viking-age Urbanism, c. 750-1100 AD. Proceedings of the International Symposium at the Swedish History Museum, April 17-20th 2013. Theses and Papers in Archaeology B THESES AND PAPERS IN ARCHAEOLOGY B New Aspects on Viking-age Urbanism, c. 750-1100 AD. Proceedings of the International Symposium at the Swedish History Museum, April 17–20th 2013 Lena Holmquist, Sven Kalmring & Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson (eds.) Contents Introduction Sigtuna: royal site and Christian town and the Lena Holmquist, Sven Kalmring & regional perspective, c. 980-1100 Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson.....................................4 Sten Tesch................................................................107 Sigtuna and excavations at the Urmakaren Early northern towns as special economic and Trädgårdsmästaren sites zones Jonas Ros.................................................................133 Sven Kalmring............................................................7 No Kingdom without a town. Anund Olofs- Spaces and places of the urban settlement of son’s policy for national independence and its Birka materiality Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson...................................16 Rune Edberg............................................................145 Birka’s defence works and harbour - linking The Schleswig waterfront - a place of major one recently ended and one newly begun significance for the emergence of the town? research project Felix Rösch..........................................................153 -

The Cyril and Methodius Mission and Europe

THE CYRIL AND METHODIUS MISSION AND EUROPE 1150 Years Since the Arrival of the Thessaloniki Brothers in Great Moravia Pavel Kouřil et al. The Institute of Archaeology of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Brno THE CYRIL AND METHODIUS MISSION AND EUROPE – 1150 Years Since the Arrival of the Thessaloniki Brothers in Great Moravia Pavel Kouřil et al. The Institute of Archaeology of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Brno Brno 2014 THE CYRIL AND METHODIUS MISSION AND EUROPE – 1150 Years Since the Arrival of the Thessaloniki Brothers in Great Moravia Pavel Kouřil et al. The publication is funded from the Ministry of Culture NAKI project „Great Moravia and 1150 years of Christianity in Central Europe“, for 2012–2015, ID Code DF12P01OVV010, sponsored as well by the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic. The Cyril and Methodius Mission and Europe – 1150 Years Since the Arrival of the Thessaloniki Brothers in Great Moravia Head of the team of authors: doc. PhDr. Pavel Kouřil, CSc. Authors: Maddalena Betti, Ph.D., prof. Ivan Biliarsky, DrSc., PhDr. Ivana Boháčová, Ph.D., PhDr. František Čajka, Ph.D., Mgr. Václav Čermák, Ph.D., PhDr. Eva Doležalová, Ph.D., doc. PhDr. Luděk Galuška, CSc., PhDr. Milan Hanuliak, DrSc., prof. PhDr. Michaela Soleiman pour Hashemi, CSc., prof. PhDr. Martin Homza, Ph.D., prof. PhDr. Petr Charvát, DrSc., prof. Sergej A. Ivanov, prof. Mgr. Libor Jan, Ph.D., prof. Dr. hab. Krzysztof Jaworski, assoc. prof. Marija A. Jovčeva, Mgr. David Kalhous, Ph.D., doc. Mgr. Antonín Kalous, M.A., Ph.D., PhDr. Blanka Kavánová, CSc., prom. -

Water Management in the Netherlands

Water management in the Netherlands The Kreekraksluizen in Schelde-Rijnkanaal Water management in the Netherlands Water: friend and foe! 2 | Directorate General for Public Works and Water Management Water management in the Netherlands | 3 The Netherlands is in a unique position on a delta, with Our infrastructure and the 'rules of the game’ for nearly two-thirds of the land lying below mean sea level. distribution of water resources still meet our needs, but The sea crashes against the sea walls from the west, while climate change and changing water usage are posing new rivers bring water from the south and east, sometimes in challenges for water managers. For this reason research large quantities. Without protective measures they would findings, innovative strength and the capacity of water regularly break their banks. And yet, we live a carefree managers to work in partnership are more important than existence protected by our dykes, dunes and storm-surge ever. And interest in water management in the Netherlands barriers. We, the Dutch, have tamed the water to create land from abroad is on the increase. In our contacts at home and suitable for habitation. abroad, we need know-how about the creation and function of our freshwater systems. Knowledge about how roles are But water is also our friend. We do, of course, need allocated and the rules that have been set are particularly sufficient quantities of clean water every day, at the right valuable. moment and in the right place, for nature, shipping, agriculture, industry, drinking water supplies, power The Directorate General for Public Works and Water generation, recreation and fisheries. -

Four Headwaters Trail Through the St Gotthard Massif

A hike to the headwaters of the Rivers Rhine, Reuss, Ticino and Rhone. Four Headwaters Trail through the St Gotthard Massif Lak e Grim - r Lake Göscheneralp sel e e i La n Göschenen ke O c Sidelen be o a raar Source of the l h Hut SAC R G Rhone Belvédère Grimsel Pass Lake 5 Tiefenbach Tote Andermatt - otthard Oberalp Pass orn-G B) Furk Matterh y (MG a mo Railwa Furka Pass (st unt Oberwald eam ain ake ra s L lp ilw e bera a ct O Gletsch y) io ne n l Realp Ulrichen ho e Hospental R n ) n s tu s e Münster e r s p Headwaters 4 a x B E B - - l GB) r B of the Rhine ne hn (M a e hi rd-Ba k e d R ha i d n S ott Obergesteln r r -G c r l orn u s n a erh F a a e att l s u h h Lake Toma M G u t t n ( t t e t n d o o u R a t G G o Tschamut y r a Vermigel Sedrun w l i Maighels Lake a Hut SAC r Hut SAC Headwaters Lucendro s of the lp Gotthard Pass a 2 1 N Nufenen Pass Gotthard-Reuss e Lake Val Maighels k a Piansecco Sella L Hut SAC Lucendro Pass Maighels Pass Lake Gries Cruina 3 Ti Headwaters cin Bedretto o Villa Airolo of the Ticino All’Acqua Ronco Stage 1 Stage 2 Stage 3 Stage 4 Stage 5 Reproduced by permission of swisstopo (BA120056) 2044 m 2345 m 2314 m 2421 m 2042 m 2042 m 2375 m 2701 m 2776 m 2256 m 2091 m 2091 m 2182 m 2522 m 2128 m 2015 m 1996 m 1938 m 1982 m 1982 m 2093 m 2003 m 2440 m 1925 m 1762 m 1533 m 1355 m 1355 m 1368 m 1550 m 1757 m 2170 m 2429 m 2271 m Oberalp Lake Maighel Maighel Vermigel Vermigel Summer- Sella Giübin Lake Gotthard Gotthard Alpe di Lucendro Rosso Ri di Ri di Ri di Piansecco Piansecco Nufenen Alpe di Nufenen Ladstafel -

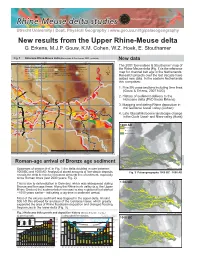

New Results from the Upper Rhine-Meuse Delta G

Utrecht University | Dept. Physical Geography | www.geo.uu.nl/fg/palaeogeography New results from the Upper Rhine-Meuse delta G. Erkens, M.J.P. Gouw, K.M. Cohen, W.Z. Hoek, E. Stouthamer Fig. 1 Holocene Rhine-Meuse delta (Berendsen & Stouthamer 2001, updated) New data 140,000 160,0005°30’E 180,000 6°0’E 200,000 220,000 The 2001 Berendsen & Stouthamer map of Fluvial channel belt age (cal yr BP) Miscellaneous Background 800 - 0 BP 3500 - 3000 6500 - 6000 Rivers, canals and lakes AHN (c) RWS-AGI 2005 the Rhine-Meuse delta (Fig. 1) is the reference Embankment 4000 - 3500 7000 - 6500 Cross sections High : 20 map for channel belt age in the Netherlands. 800 - 1500 4500 - 4000 7500 - 7000 A-E Gouw and Erkens NJG 2007 Low : -10 2000 - 1500 5000 - 4500 8000 - 7500 Betuwelijn section, B&S 2001 Research projects over the last decade have Utr. Vecht 2500 - 2000 5500 - 5000 8500 - 8000 3000 - 2500 6000 - 5500 added new data. In the eastern Netherlands E’ ,000 460 this comprises: Utrecht 1. Five SN cross-sections including time lines IJssel D’ (Gouw & Erkens, 2007 NJG) 2. History of sediment delivery to the Arnhem Oude IJssel C’ B’ A’ 52°0’N Holocene delta (PhD thesis Erkens) ,000 3. Mapping and dating Rhine deposition in 440 the Gelderse IJssel valley (Cohen) Linge 4. Late Glacial/Holocene landscape change in the Oude IJssel- and Niers-valley (Hoek) A Waal Nijmegen Rhine 1000 AD Embanked rivers C ,000 B 420 Former rivers Meuse River floodbasin D Den Bosch E G E R M A N Y Meuse 51°40’N Niers 0 10 20 30 40 km 140,000 160,0005°30’E 180,000 6°0’E200,000 220,000 Roman-age arrival of Bronze age sediment Upstream of section A-A in Fig. -

Download (PDF)

5 CHURCH OF St MAURICE damaged during the 30 Years’ War by the Swedish Army 12 CHURCH OF St GORAZD Christ’s Crucifixion.t he Crucifixion itself is located directly Church Union in 1925. the project was processed by the and following the fire of 1709, the Baroque interior of upon entering the chapel, which was canonized together architect and developer Josef Salek. Building commenced the Olomouc parish church from the beginning the church was renovated. the Orthodox Church of St Gorazd is a symmetrical seg- with the column in 1754 during the reign of Marie theresa. on September 16th, 1929 and was completed in 1932, of the 15th century is typical for its two asym- A complex building of the former monastery adjoins mented building, which at first glance significantly differs under the leadership of contractors Jindrich Kylian and metrical prismatic towers as well as its highly arched three- the church. today, with the exception of the church, the from the other Olomouc churches. It culminates with an 15 PILGRIMAGE CHURCH ON HOLY HILL tomas Sipka. the interior décor is dominated by a massive naved structure and therefore, rightfully is part of the unique monastery is privately owned. octagonal tower, topped with a gilded bulbous dome with mosaic, entirely in presbytery from the painter, Jano Köhler. late Gothic structure of Moravia. At the end of the 16th cen- a cross, which clearly refers to the obvious source of inspi- the Baroque basilica, with its double tower façade, sig- the organ with thirty registers was made by the Rieger bro- tury, two renaissance burial chapels of the noble Edelmann ration of the traditional Byzantine-like architecture of the nificantly dominates the Olomouc countryside. -

The Age and Origin of the Gelderse Ijssel

Netherlands Journal of Geosciences — Geologie en Mijnbouw | 87 – 4 | 323 - 337 | 2008 The age and origin of the Gelderse IJssel B. Makaske1,*, G.J. Maas1 & D.G. van Smeerdijk2 1 Alterra, Wageningen University and Research Centre, P.O. Box 47, 6700 AA Wageningen, the Netherlands. 2 BIAX Consult, Hogendijk 134, 1506 AL Zaandam, the Netherlands. * Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Manuscript received: February 2008; accepted: September 2008 Abstract The Gelderse IJssel is the third major distributary of the Rhine in the Netherlands and diverts on average ~15% of the Rhine discharge northward. Historic trading cities are located on the Gelderse IJssel and flourished in the late Middle Ages. Little is known about this river in the early Middle Ages and before, and there is considerable debate on the age and origin of the Gelderse IJssel as a Rhine distributary. A small river draining the surrounding Pleistocene uplands must have been present in the IJssel valley during most of the Holocene, but very diverse opinions exist as to when this local river became connected to the Rhine system (and thereby to a vast hinterland), and whether this was human induced or a natural process. We collected new AMS radiocarbon evidence on the timing of beginning overbank sedimentation along the lower reach of the Gelderse IJssel. Our data indicate onset of overbank sedimentation at about 950 AD in this reach. We attribute this environmental change to the establishment of a connection between the precursor of the IJssel and the Rhine system by avulsion. Analysis of previous conventional radiocarbon dates from the upper IJssel floodplain yields that this avulsion may have started ~600 AD. -

Rivers in the Sky, Flooding on the Ground

https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-2020-149 Preprint. Discussion started: 14 April 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. Rivers in the sky, flooding on the ground Monica Ionita1, Viorica Nagavciuc1,2 and Bin Guan3,4 1 Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, Bremerhaven, 27570, Germany 2 Faculty of Forestry, Ștefan cel Mare University, Suceava, 720229, Romania 5 3 Joint Institute for Regional Earth System Science and Engineering, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 4 Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA Correspondence to: Monica Ionita ([email protected]) Abstract. The role of the large scale atmospheric circulation and atmospheric rivers (ARs) in producing extreme flooding and heavy rainfall events in the lower part of Rhine River catchment area is examined in this study. Analysis of the largest 10 10 floods in the lower Rhine, between 1817 – 2015, indicate that all these extreme flood peaks have been preceded up to 7 days in advance by intense moisture transport from the tropical North Atlantic basin, in the form of narrow bands, also know as atmospheric rivers. The influence of ARs on the Rhine River flood events is done via the prevailing large-scale atmospheric circulation. Most of the ARs associated with these flood events are embedded in the trailing fronts of the extratropical cyclones. The typical large scale atmospheric circulation leading to heavy rainfall and flooding in the lower 15 Rhine is characterized by a low pressure center south of Greenland which migrates towards Europe and a stable high pressure center over the northern part of Africa and southern part of Europe.