The Cyril and Methodius Mission and Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dokument B.Indd

část B - nová infrastruktura Rozvoj linek PID v Praze 2019-2029 Rozvoj linek PID 2019-2029 část B (nová infrastruktura) © Odbor městské dopravy, Ropid 2018 sazba a design: Ing. arch. Václav Brejška, provozní bilance: David Marek výpočet výkonů: Ing. Blanka Brožová strategie snižování emisí autobusů: Ing. Jan Barchánek zástupce vedoucího projektu: Ing. Martin Šubrt vedoucí projektu: Ing. Martin Fafejta 3 Obsah Úvod Dokument „Rozvoj linek PID v Praze 2019-2029“ zachycuje předpokládaný vývoj linkového vedení Úvod 5 PID na území hl. m. Prahy v následujících deseti letech. Tento vývoj je zpracován v kontextu realizací no- vých projektů na síti kolejové dopravy, v souvislosti s další komerční a bytovou zástavbou v jednotlivých Vysvětlivky, symboly a struktura hesel 6 lokalitách Prahy, s předpokládaným růstem přepravní poptávky a v řadě míst reaguje i na výhledové po- Opatření B.01-B.19 – Úvod k novým infrastrukturním projektům 9 žadavky městských částí. Základním cílem dokumentu je poskytnout městské samosprávě i veřejnosti podrobnější před- Opatření B.01 - TT Levského - Libuš, Autobusové obratiště Šabatka 11 stavu o tom, jakou podobu hromadné dopravy mohou v okolí svého bydliště očekávat po dokončení no- vých tras metra, tratí tramvají, modernizací železničních tratí a po dostavbě dalších obytných a adminis- Opatření B.02 - Tramvajová smyčka Depo Hostivař 17 trativních celků. Opatření B.03 - TT Divoká Šárka - Dědina 21 Dokument si dále klade za cíl popsat, jaký objem hromadné dopravy bude na nových úsecích možné očekávat. Bude sloužit jako podklad pro výpočet vývoje objemu objednaných vozokilometrů PID Opatření B.04 - TT Sídliště Barrandov - Slivenec, Železniční trať Smíchov - Radotín 27 na území hl. -

Saint ADALBERT and Central Europe

POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC SLOVAKIA AUSTRIA HUNGARY SLO CRO ITALY BiH SERBIA ME BG Saint ADALBERT and Central Europe Patrimonium Sancti Adalberti Collective of Authors Patrimonium Sancti Adalberti Society issued this collection of essays as its first publication in 2021. I/2021 Issuing of the publication was supported by companies: ZVVZ GROUP, a.s. RUDOLF JELÍNEK a.s. PNEUKOM, spol. s r.o. ISBN 978-80-270-9768-5 Saint ADALBERT and Central Europe Issuing of the publication was supported by companies: Collective of Authors: Petr Bahník Jaroslav Bašta Petr Drulák Aleš Dvořák Petr Charvát Stanislav Janský Zdeněk Koudelka Adam Kretschmer Radomír Malý Martin Pecina Igor Volný Zdeněk Žák Introductory Word: Prokop Siostrzonek A word in conclusion: Tomáš Jirsa Editors: Tomáš Kulman, Michal Semín Publisher: Patrimonium Sancti Adalberti, z.s. Markétská 1/28, 169 00 Prague 6 - Břevnov Czech Republic [email protected] www.psazs.cz Cover: Statue of St. Adalbert from the monument of St. Wenceslas on Wenceslas Square in Prague Registration at Ministry of the Culture (Czech Republic): MK ČR E 24182 ISBN 978-80-270-9768-5 4 / Prokop Siostrzonek Introductory word 6 / Petr Bahník Content Pax Christiana of Saint Slavník 14 / Radomír Malý Saint Adalbert – the common patron of Central European nations 19 / Petr Charvát The life and work of Saint Adalbert 23 / Aleš Dvořák Historical development and contradictory concepts of efforts to unite Europe 32 / Petr Drulák A dangerous world and the Central European integration as a necessity 41 / Stanislav Janský Central Europe -

Crusading, the Military Orders, and Sacred Landscapes in the Baltic, 13Th – 14Th Centuries ______

TERRA MATRIS: CRUSADING, THE MILITARY ORDERS, AND SACRED LANDSCAPES IN THE BALTIC, 13TH – 14TH CENTURIES ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the School of History, Archaeology and Religion Cardiff University ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in History & Welsh History (2018) ____________________________________ by Gregory Leighton Abstract Crusading and the military orders have, at their roots, a strong focus on place, namely the Holy Land and the shrines associated with the life of Christ on Earth. Both concepts spread to other frontiers in Europe (notably Spain and the Baltic) in a very quick fashion. Therefore, this thesis investigates the ways that this focus on place and landscape changed over time, when crusading and the military orders emerged in the Baltic region, a land with no Christian holy places. Taking this fact as a point of departure, the following thesis focuses on the crusades to the Baltic Sea Region during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. It considers the role of the military orders in the region (primarily the Order of the Teutonic Knights), and how their participation in the conversion-led crusading missions there helped to shape a distinct perception of the Baltic region as a new sacred (i.e. Christian) landscape. Structured around four chapters, the thesis discusses the emergence of a new sacred landscape thematically. Following an overview of the military orders and the role of sacred landscpaes in their ideology, and an overview of the historiographical debates on the Baltic crusades, it addresses the paganism of the landscape in the written sources predating the crusades, in addition to the narrative, legal, and visual evidence of the crusade period (Chapter 1). -

A Dictionary of Orthodox Terminology Fotios K. Litsas, Ph.D

- Dictionary of Orthodox Terminology Page 1 of 25 Dictionary of Orthodox Terminology A Dictionary of Orthodox Terminology Fotios K. Litsas, Ph.D. -A- Abbess. (from masc. abbot; Gr. Hegoumeni ). The female superior of a community of nuns appointed by a bishop; Mother Superior. She has general authority over her community and nunnery under the supervision of a bishop. Abbot. (from Aram. abba , father; Gr. Hegoumenos , Sl. Nastoyatel ). The head of a monastic community or monastery, appointed by a bishop or elected by the members of the community. He has ordinary jurisdiction and authority over his monastery, serving in particular as spiritual father and guiding the members of his community. Abstinence. (Gr. Nisteia ). A penitential practice consisting of voluntary deprivation of certain foods for religious reasons. In the Orthodox Church, days of abstinence are observed on Wednesdays and Fridays, or other specific periods, such as the Great Lent (see fasting). Acolyte. The follower of a priest; a person assisting the priest in church ceremonies or services. In the early Church, the acolytes were adults; today, however, his duties are performed by children (altar boys). Aër. (Sl. Vozdukh ). The largest of the three veils used for covering the paten and the chalice during or after the Eucharist. It represents the shroud of Christ. When the creed is read, the priest shakes it over the chalice, symbolizing the descent of the Holy Spirit. Affinity. (Gr. Syngeneia ). The spiritual relationship existing between an individual and his spouse’s relatives, or most especially between godparents and godchildren. The Orthodox Church considers affinity an impediment to marriage. -

A1a 11 M-P A2a 12 M-1A/A A2b 13 M-1A/B A3a 14 M-1B/A A3b 15 M-1B

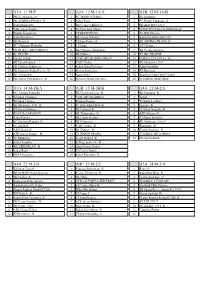

A1A 11 M-P A2A 12 M-1A/A A2B 13 M-1A/B 1 FK Újezd nad Lesy 1 FC TEMPO PRAHA 1 SK Modřany 2 FK ADMIRA PRAHA B 2 Sokol Troja 2 FC Přední Kopanina B 3 Sokol Kolovraty 3 SK Čechie Uhříněves 3 FK ZLÍCHOV 1914 4 AFK Slavoj Podolí 4 FC Háje Jižní Město 4 SPORTOVNÍ KLUB ZBRASLAV 5 Přední Kopanina 5 TJ BŘEZINĚVES 5 TJ AFK Slivenec 6 Sokol Královice 6 SK Union Vršovice 6 Sportovní klub Libuš 838 7 SK Hostivař 7 TJ Kyje Praha 14 7 SK ARITMA PRAHA B 8 SC Olympia Radotín 8 TJ Praga 8 1999 Praha 9 FK DUKLA JIŽNÍ MĚSTO 9 SK Viktoria Štěrboholy 9 SK Čechie Smíchov 10 FC ZLIČÍN 10 SK Ďáblice 10 TJ ABC BRANÍK 11 Uhelné sklady 11 TJ SPARTAK HRDLOŘEZY 11 LOKO VLTAVÍN z.s. B 12 SK Újezd Praha 4 12 ČAFC Praha 12 SK Střešovice 1911 13 FK Viktoria Žižkov a.s. 13 Sokol Dolní Počernice 13 Sokol Stodůlky 14 FK Motorlet Praha B s.r.o. B 14 Slovan Kunratice 14 FK Řeporyje 15 SK Třeboradice 15 Spoje Praha 15 Sportovní klub Dolní Chabry 16 FK Slavoj Vyšehrad a.s. B 16 Xaverov Horní Počernice 16 TJ SOKOL NEBUŠICE A3A 14 M-1B/A A3B 15 M-1B/B A4A 21 M-2/A 1 FC Tempo Praha B 1 FK Újezd nad Lesy B 1 SK Modřany B 2 TJ Sokol Cholupice 2 TJ SPARTAK KBELY 2 Točná 3 TJ Sokol Lipence 3 Partisan Prague 3 TJ Sokol Lochkov 4 SK Střešovice 1911 B 4 FC Háje Jižní Město B 4 Lipence B 5 TJ Slovan Bohnice 5 SK Hostivař B 5 TJ Sokol Nebušice B 6 TJ AVIA ČAKOVICE 6 SK Třeboradice B 6 AFK Slivenec B 7 Sokol Písnice 7 FK Union Strašnice 7 TJ Slavoj Suchdol 8 SC Olympia Radotín B 8 FK Klánovice 8 SK Střešovice 1911 C 9 FC Zličín B 9 ČAFC Praha B 9 Řeporyje B 10 ABC Braník B 10 SK Ďáblice -

Echa Przeszłości 11/2010

2 Irena Makarczyk Rada Redakcyjna Stanis³aw Achremczyk, Daniel Beauvois, Stanis³aw Gajewski, Stefan Hartmann, Zoja Jaroszewicz-Pieres³awcew, Janusz Jasiñski, S³awomir Kalembka , Marek K. Kamiñski, Norbert Kasparek (przewodnicz¹cy), Andrzej Kopiczko, Giennadij Krietinin, Kazimierz £atak, Bohdan £ukaszewicz, Jens E. Olesen, Bohdan Ryszewski, Jan Sobczak, Alojzy Szorc Redakcja Jan Gancewski (sekretarz), Witold Gieszczyñski (redaktor naczelny), Roman Jurkowski, Norbert Kasparek Recenzenci Jan Dziêgielewski, Zbigniew Opacki Adres Redakcji Instytut Historii i Stosunków Miêdzynarodowych UWM, ul. Kurta Obitza 1 10-725 Olsztyn, tel./fax 089-527-36-12, tel. 089-524-64-35 e-mail: [email protected] http://human.uwm.edu.pl/historia/echa.htm Projekt ok³adki Barbara Lis-Romañczukowa Redakcja wydawnicza Danuta Jamio³kowska T³umaczenie na jêzyk angielski Aleksandra Poprawska ISSN 1509-9873 © Copyright by Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warmiñsko-Mazurskiego w Olsztynie Olsztyn 2010 Nak³ad 155 egz. Ark. wyd. 36,8; ark. druk. 31,25; pap. druk. kl. III Druk Zak³ad Poligraficzny Uniwersytetu Warmiñsko-Mazurskiego w Olsztynie zam. 653 SPIS TRECI ARTYKU£Y I ROZPRAWY Krzysztof Tomasz Witczak, Ksi¹¿ê stodorañski Têgomir próba rehabilitacji .......... 7 Pavel Krafl, Prawo kocielne w Czechach i na Morawach w redniowieczu .............. 19 Grzegorz Bia³uñski, Uwagi o udziale chor¹gwi che³miñskiej w bitwie grunwaldzkiej ........................................................................................................... 37 Anna Ko³odziejczyk, Regulacje prawne -

Anniversary of the Dedication of the Monastic Church of Holy Cross Monastery (Rostrevor) (Ephesians 2:19-22 / John 4:19-24) 18.01.2015

Anniversary of the Dedication of the Monastic Church of Holy Cross Monastery (Rostrevor) (Ephesians 2:19-22 / John 4:19-24) 18.01.2015 Right Rev Dom Hugh Gilbert OSB (Bishop of Aberdeen) Around the year 600, a Spanish bishop – Isidore of Seville – wrote a book on the liturgy of the Church. And one of the chapters is on ‘Temples’ – in our terms, ‘On the Dedication of Churches’. It’s very short and it says this: “Moses, the lawgiver, was the first to dedicate a Tabernacle to the Lord. Then Solomon ... established the Temple. After these, in our own times, faith has consecrated buildings for Christ throughout the world.” The word that jumps out there is the word “faith”. Faith, he says, “has consecrated buildings for Christ throughout the world.” He has mentioned Moses and Solomon. What we’d expect, when he gets to now, is bishops consecrate buildings for Christ. They do, after all. Bishop John dedicated this church on 18 January 2004. And it was the same in St. Isidore’s day. But he goes deeper. He goes to what makes us Christians and come together in community. He goes to the root which makes us build churches in the first place and want them to be consecrated. He goes back to what gathers people round their bishop and to what moves the bishop to celebrate the liturgy for us. He goes back to what brings us here week after week, and the monks five times a day: faith. “After these – after the Tabernacle and the Temple – in our own times, faith has consecrated buildings for Christ throughout the world.” This is what it is about! We’re familiar with chapter 11 of the Letter to the Hebrews. -

Die Kirche Und Die „Kärntner Seele“

Open Access © 2019 by BÖHLAU VERLAG GMBH & CO.KG, WIEN KÖLN WEIMAR Johannes Thonhauser Die Kirche und die »Kärntner Seele« Habitus, kulturelles Gedächtnis und katholische Kirche in Kärnten, insbesondere vor 1938 Böhlau Verlag Wien Köln Weimar Veröffentlicht mit der Unterstützung des Austrian Science Fund (FWF): PUB 612-G28 Open Access: Wo nicht anders festgehalten, ist diese Publikation lizenziert unter der Creative-Commons- Lizenz Namensnennung 4.0; siehe http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Die Publikation wurde einem anonymen, internationalen Peer-Review-Verfahren unterzogen Bibliografsche Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek : Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografe ; detaillierte bibliografsche Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. © 2019 by Böhlau Verlag Ges.m.b.H & Co. KG, Wien, Kölblgasse 8–10, A-1030 Wien Umschlagabbildung : Krypta des Gurker Domes. Foto: Martin Siepmann Korrektorat : Jörg Eipper-Kaiser, Graz Einbandgestaltung : Michael Haderer, Wien Satz : Michael Rauscher, Wien Druck und Bindung : Prime Rate, Budapest Gedruckt auf chlor- und säurefrei gebleichtem Papier Printed in the EU Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Verlage | www.vandenhoeck-ruprecht-verlage.com ISBN 978-3-205-23291-9 Open Access © 2019 by BÖHLAU VERLAG GMBH & CO.KG, WIEN KÖLN WEIMAR Inhaltsverzeichnis Danksagung .................................... 11 Einleitung Die katholische Kirche und der Sonderfall Kärnten ............. 13 1 Vorbemerkungen .............................. 13 2 Hinführung ................................. 17 2.1 Empirische Befunde zur Wahrnehmung der Kirche in Kärnten ... 18 2.2 Der Sonderfall Kärnten und die Kirche ................. 23 3 Theoretische Vorüberlegungen ...................... 30 3.1 Soziologische Grundannahmen ...................... 31 3.2 Kulturelles und kollektives Gedächtnis ................. 39 3.3 Zum methodischen Umgang mit Kunst und Literatur ......... 49 Erster Teil Kirche und Habitusentwicklung in Kärnten ................. -

Droughts in the Czech Lands, 1090–2012 AD Open Access Geoscientific Geoscientific Open Access 1,2 1,2 2,3 4 1,2 5 2,6 R

EGU Journal Logos (RGB) Open Access Open Access Open Access Advances in Annales Nonlinear Processes Geosciences Geophysicae in Geophysics Open Access Open Access Natural Hazards Natural Hazards and Earth System and Earth System Sciences Sciences Discussions Open Access Open Access Atmospheric Atmospheric Chemistry Chemistry and Physics and Physics Discussions Open Access Open Access Atmospheric Atmospheric Measurement Measurement Techniques Techniques Discussions Open Access Open Access Biogeosciences Biogeosciences Discussions Open Access Open Access Clim. Past, 9, 1985–2002, 2013 Climate www.clim-past.net/9/1985/2013/ Climate doi:10.5194/cp-9-1985-2013 of the Past of the Past © Author(s) 2013. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Discussions Open Access Open Access Earth System Earth System Dynamics Dynamics Discussions Droughts in the Czech Lands, 1090–2012 AD Open Access Geoscientific Geoscientific Open Access 1,2 1,2 2,3 4 1,2 5 2,6 R. Brazdil´ , P. Dobrovolny´ , M. Trnka , O. Kotyza , L. Reznˇ ´ıckovˇ a´ , H. Vala´sekˇ Instrumentation, P. Zahradn´ıcekˇ , and Instrumentation P. Stˇ epˇ anek´ 2,6 Methods and Methods and 1Institute of Geography, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic 2Global Change Research Centre AV CR,ˇ Brno, Czech Republic Data Systems Data Systems 3Institute of Agrosystems and Bioclimatology, Mendel University in Brno, Czech Republic Discussions Open Access 4 Open Access Regional Museum, Litomeˇrice,ˇ Czech Republic Geoscientific 5Moravian Land Archives, Brno, Czech Republic Geoscientific 6 Model Development Czech Hydrometeorological Institute, Brno, Czech Republic Model Development Discussions Correspondence to: R. Brazdil´ ([email protected]) Open Access Received: 29 April 2013 – Published in Clim. Past Discuss.: 8 May 2013 Open Access Revised: 4 July 2013 – Accepted: 8 July 2013 – Published: 20 August 2013 Hydrology and Hydrology and Earth System Earth System Abstract. -

Выпуск 9 Issn 2079-1488

ВЫПУСК 9 ISSN 2079-1488 ГОСУДАРСТВЕННОЕ УЧРЕЖДЕНИЕ ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ «РЕСПУБЛИКАНСКИЙ ИНСТИТУТ ВЫСШЕЙ ШКОЛЫ» КАФЕДРА ИСТОРИКО-КУЛЬТУРНОГО НАСЛЕДИЯ БЕЛАРУСИ Научный сборник Основан в 2008 году ВЫПУСК 9 Минск РИВШ 2016 УДК 94(4-11)(082) Рекомендовано редакционно-издательской комиссией государственного учреждения образования «Республиканский институт высшей школы» (протокол № 6 от 30 декабря 2015 г.) Редакционная коллегия: А. В. Мартынюк – кандидат исторических наук, отв. редактор (Минск) Г. Я. Голенченко – доктор исторических наук, зам. отв. редактора (Минск) О. А. Яновский – кандидат исторических наук, зам. отв. редактора (Минск) А. А. Любая – кандидат исторических наук, зам. отв. редактора (Минск) Ю. Н. Бохан – доктор исторических наук (Минск) М. Вайерс – доктор исторических наук (Бонн) В. А. Воронин – кандидат исторических наук (Минск) О. И. Дзярнович – кандидат исторических наук (Минск) Д. Домбровский – доктор исторических наук (Быдгощ) Л. В. Левшун – доктор филологических наук (Минск) А. В. Любый – кандидат исторических наук (Минск) И. А. Марзалюк – доктор исторических наук (Могилев) В. Нагирный – доктор истории (Краков) Н. В. Николаев – доктор филологических наук (Санкт-Петербург) В. А. Теплова – кандидат исторических наук (Минск) В. А. Федосик – доктор исторических наук (Минск) А. И. Филюшкин – доктор исторических наук (Санкт-Петербург) А. Л. Хорошкевич – доктор исторических наук (Москва) В. Янкаускас – доктор истории (Каунас) Studia Historica Europae Orientalis = Исследования по истории И87 Восточной Европы : науч. сб. Вып. 9. – Минск : РИВШ, 2016. – 252 с. В научном сборнике представлены актуальные исследования белорусских и зарубежных ученых, посвященные широкому кругу проблем истории Вос- точной Европы в Средние века и раннее Новое время. Сборник включен ВАК Республики Беларусь в перечень научных изданий для опубликования резуль- татов диссертационных исследований по историческим наукам. Адресуется студентам, аспирантам, преподавателям и научным работни- кам, а также всем, кто интересуется историей восточных славян. -

ANZAC Day Resources

ANZAC Day Worship Resource Content Preface …3 Introduction …4 Service of Remembrance …5 Gathering …6 Word ...13 Remembrance …17 Sending …24 General Prayers …26 Hymn Suggestions …30 Public Services …33 Images Front Page 3rd Light Horse Chap Merrington 1915 Gallipoli Page 3 3rd Light Horse Burial ANZAC Day 1917 Cairo Page 5 1st Light Horse Funeral at Cairo Presbyterian Cemetary 1914-15 Page 6 CoE RC and Presb. Chaplains bury four British soldiers 1915 Page 13 Church parade at Ryrie's Post 1915 Gallipoli Page 17 3rd Light Horse Chap Merrington 1915 Gallipoli Page 25 Grave of an Australian Soldier 1915 Gallipoli Page 27 Soldiers on Gallipoli listening to sermon 1915 Page 31 Chaplain writing field card Greece, Date Unknown Page 34 Brockton WA WW! Memorial after ANZAC Day Service !2 Preface This resource has been compiled by Uniting Church in Australia ministers who are current- ly in placement as Chaplains in the Australian Defence Force. Some of them have seen deployments in places of war and served for many years while others are new to this min- istry who care for sailors, soldiers and airmen and women in the ADF and their families. These traditional and interactive prayers have been provided for congregations that will be remembering Australians throughout the centenary year of World War 1 and in particular the landings at Gallipoli. The prayers in this resource have been broken up in light of the four fold structure of wor- ship, as found in Uniting in Worship 2: Gathering, Word, Remembrance, and Sending. There is a fifth section which has been compiled from prayers used by Chaplains in public services, such as ANZAC Days and Remembrance Days. -

The Impact of the Roman Army (200 BC – AD 476)

Impact of Empire 6 IMEM-6-deBlois_CS2.indd i 5-4-2007 8:35:52 Impact of Empire Editorial Board of the series Impact of Empire (= Management Team of the Network Impact of Empire) Lukas de Blois, Angelos Chaniotis Ségolène Demougin, Olivier Hekster, Gerda de Kleijn Luuk de Ligt, Elio Lo Cascio, Michael Peachin John Rich, and Christian Witschel Executive Secretariat of the Series and the Network Lukas de Blois, Olivier Hekster Gerda de Kleijn and John Rich Radboud University of Nijmegen, Erasmusplein 1, P.O. Box 9103, 6500 HD Nijmegen, The Netherlands E-mail addresses: [email protected] and [email protected] Academic Board of the International Network Impact of Empire geza alföldy – stéphane benoist – anthony birley christer bruun – john drinkwater – werner eck – peter funke andrea giardina – johannes hahn – fik meijer – onno van nijf marie-thérèse raepsaet-charlier – john richardson bert van der spek – richard talbert – willem zwalve VOLUME 6 IMEM-6-deBlois_CS2.indd ii 5-4-2007 8:35:52 The Impact of the Roman Army (200 BC – AD 476) Economic, Social, Political, Religious and Cultural Aspects Proceedings of the Sixth Workshop of the International Network Impact of Empire (Roman Empire, 200 B.C. – A.D. 476) Capri, March 29 – April 2, 2005 Edited by Lukas de Blois & Elio Lo Cascio With the Aid of Olivier Hekster & Gerda de Kleijn LEIDEN • BOSTON 2007 This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.