Telecom & Media Sector in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Releases, SEC Filings, Recent News, Financial Results, and Other Announcements

Press Contact: Shannon N. Booker Ciena Corporation +1 (410) 865-8570 [email protected] Investor Contact: Gregg Lampf Ciena Corporation +1 (410) 694-5700 [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Tele2 Netherlands Improves Network Performance Using Ciena’s WaveLogic Ai Spike in mobile data usage drives the need for an adaptive network that scales up to 400G HANOVER, Md. – September 10, 2018 – Tele2 Netherlands, a leading regional telecommunications service provider, recently deployed Ciena’s (NYSE: CIEN) WaveLogic Ai coherent optical solution to increase the capacity of its network, lower operating costs and support a tremendous increase in mobile video data traffic driven by Netflix™ and YouTube™. Key Facts: • Tele2 Netherlands is a telecommunications service provider supporting the Dutch market. Tele2 Netherlands services both domestic and large enterprise customers, and manages a portfolio of fixed telephone, mobile phone, broadband and digital television products. • Using Ciena’s 6500 packet-optical platform powered by WaveLogic Ai, the industry’s first programmable coherent modem that can scale to 400Gbps per wavelength, Tele2 Netherlands can deploy 300G and 400G wavelengths across most of its existing network. The platform enables Tele2 Netherlands to effectively address a significant surge of mobile data usage from customers who are taking advantage of the service provider’s unlimited bundles for voice and mobile internet services. • WaveLogic Ai enables Tele2 Netherlands to leverage existing network assets and deliver up to forty times the bandwidth the network was originally designed to support. The service provider also benefits from a smaller footprint, reduced cost per bit and power consumption and lower cooling requirements. -

Jon James to Leave Tele2 Following the Merger in the Netherlands

Jon James to leave Tele2 following the merger in the Netherlands Stockholm – Tele2 AB (Tele2) (Nasdaq Stockholm: TEL2 A and TEL2 B) today announces that Jon James, Executive Vice President and former CEO Tele2 Netherlands leaves the Leadership Team and Tele2 at the end of June. Following the merger of Tele2 and T-Mobile in the Netherlands, announced on January 2nd2019, Jon James, Executive Vice President and former CEO Tele2 Netherlands, will officially leave Tele2 at the end of June 2019. – Jon joined Tele2 in 2017 and has been a crucial driver behind the turnaround of Tele2’s Dutch operations, ultimately culminating with the merger. Jon and I have worked together for many years and he has contributed greatly to both the success of Com Hem and Tele2 in his two most recent positions. I want to thank Jon for his leadership and engagement, and I wish him the best of luck in whatever challenges he will take on in the future, says Anders Nilsson, President and CEO, Tele2. – It is a source of great satisfaction to have secured, in just two years, a significant organizational transformation of Tele2 Netherlands plus the successful T-Mobile merger with an unconditional European clearance. This reflects great credit on the Tele2 team, in particular my Dutch colleagues, and I wish them all the best for the future, says Jon James, Executive Vice President and former CEO Tele2 Netherlands. For more information, please contact: Joel Ibson, Head of Corporate Communications, Tele2 AB, Phone: +46 766 26 44 00 Erik Strandin Pers, Head of Investor Relations, Tele2 AB, Phone: +46 733 41 41 88 TELE2’S MISSION IS TO FEARLESSLY LIBERATE PEOPLE TO LIVE A MORE CONNECTED LIFE. -

ITU Operational Bulletin Telecommunication Union

International ITU Operational Bulletin Telecommunication Union No. 850 15.XII.2005 (Information received by 8 December 2005) Table of Contents Page General information Lists annexed to the ITU Operational Bulletin: Note from TSB.............................................................. 2 Approval of ITU-T Recommendations................................................................................................... 3 Assignment of Signalling Area/Network Codes (SANC) (ITU-T Recommendation Q.708 (03/1999)): Note from TSB).................................................................................................................................. 4 International Public Telecommunication Numbering Plan (ITU-T Recommendation E.164 (02/2005)): Identification Codes for International Networks ................................................................................ 5 Telephone Service: Afghanistan (Ministry of Communications (MoC), Kabul)............................................................. 5 Denmark (National IT and Telecom Agency (NITA), Copenhagen) ............................................... 6 Egypt (National Telecom Regulatory Authority (NTRA), Cairo) ..................................................... 6 New Zealand (Ministry of Economic Development, Wellington) ................................................... 8 Niger (Société Nigérienne des Télécommunications (SONITEL), Niamey)...................................... 9 Service Restrictions: Note from TSB .................................................................................................... -

Corporate Governance Report 2017 Corporate Governance Report 2017

Corporate Governance Report 2017 Corporate Governance Report 2017 Tele2 in brief Tele2 AB (publ) (“Tele2” or the “company”) has 15 million custom- mandatory law and rules, applies Nasdaq Stockholm’s Rule Book for ers in seven countries and offers mobile services, fixed broadband Issuers Nasdaq Stockholm and the Swedish Corporate Governance and telephony, data network services, content services and global Code (“the Code”). IoT solutions. In 2017, the company had net sales of SEK 25 (21) bil- This Corporate Governance Report is published separately lion and reported EBITDA of SEK 6.4 (5.4) billion. Tele2's divestment from the Annual Report and prepared in accordance with the of its Austrian operations to Hutchison Drei Austria GmbH (Three Swedish Annual Accounts Act and the provisions of the Code. Austria) was closed on October 31, 2017. On December 15, 2017, Previous years’ Corporate Governance Reports and other corporate Tele2 and Deutsche Telekom agreed to combine Tele2 Netherlands governance documents are available on the corporate website, and T-Mobile Netherlands where Tele2 will hold a 25% share www.tele2.com. The Code is based on the principle of comply or in the combined company. Tele2 Austria and Tele2 Netherlands explain, which means that companies can deviate from single rules have been reported as discontinued operations and therefore not in the Code, provided that they offer an explanation for the devia- included above. Tele2 is a Swedish limited liability company with tion. Tele2 has not deviated from the Code during 2017. shares listed on the Nasdaq Stockholm and thus, in addition to Overview of corporate governance at Tele2 Sound corporate governance at Tele2 means the establishment supports the understanding and monitoring of the development of of an appropriate framework for decision making, assignment of the company. -

ITU Operational Bulletin No. 869 – 3

ITU Operational Bulletin No. 869 1.X.2006 (Information received by 25 September 2006) Table of Contents Page General information Lists annexed to the ITU Operational Bulletin: Note from TSB.............................................................. 3 Approval of ITU-T Recommendations................................................................................................... 4 Assignment of Signalling Area/Network Codes (SANC) (ITU-T Recommendation Q.708 (03/1999)): Monaco, Norway.............................................................................................................................. 4 Telephone Service: Burkina Faso (Autorité Nationale de Régulation des Télécommunications (ARTEL), Ouagadougou)........................................................................................................................... 5 Denmark (National IT and Telecom Agency (NITA), Copenhagen) ............................................... 5 United Arab Emirates (Telecommunications Regulatory Authority (TRA), Abu Dhabi).................. 5 Gambia (The Gambia Public Utilities Regulatory Authority (PURA), Kololi) ................................... 7 Guatemala (Superintendencia de Telecomunicaciones, Guatemala)............................................. 8 Guyana (Guyana Telephone & Telegraph Co. Ltd, Georgetown).................................................. 11 Jamaica (Office of Utilities Regulation (OUR), Kingston)............................................................... 12 Serbia (Republic Telecommunication Agency, -

Wireless Logic Mdex SMS Reachlist

Wireless Logic mdex SMS reachlist 01.10.2020 This information is given to the best of our knowledge. No responsibility is accepted for the accuracy of this information. This list is subject to change without notice. ISO 3166- Country Price- Region Country Carrier Network MNP MCC MNC 1 alpha-2 Code group Eastern Europe Abkhazia unknown unknown AB 7940 289 unknown 1 Eastern Europe Abkhazia Aquafon n.a. AB 7940 289 67 1 Eastern Europe Abkhazia JV A-Mobile Ltd. A-Mobile AB 7940 289 88 1 Middle East Afghanistan unknown unknown AF 93 412 unknown 1 Middle East Afghanistan AWCC AWCC AF 93 412 01 1 Middle East Afghanistan Roshan Roshan AF 93 412 20 1 Middle East Afghanistan MTN Afghanistan MTN Afghanistan AF 93 412 40 1 Middle East Afghanistan Etisalat Afghanistan Etisalat Afghanistan AF 93 412 50 1 Middle East Afghanistan Salaam Network Salaam Network AF 93 412 80 1 Eastern Europe Albania unknown unknown YES AL 355 276 unknown 1 Eastern Europe Albania AMC AMC YES AL 355 276 01 1 Eastern Europe Albania Vodafone Albania Vodafone Albania YES AL 355 276 02 1 Eastern Europe Albania Eagle Mobile Eagle Mobile YES AL 355 276 03 1 Eastern Europe Albania Albania Plus Communication PLUS YES AL 355 276 04 1 Africa Algeria unknown unknown DZ 213 603 unknown 1 Africa Algeria Mobilis Mobilis DZ 213 603 01 1 Africa Algeria Djezzy Djezzy DZ 213 603 02 1 Africa Algeria Wataniya Wataniya DZ 213 603 03 1 Oceania American Samoa unknown unknown AS 684 544 unknown 1 Europe Andorra unknown unknown AD 376 213 unknown 1 Europe Andorra Mobiland Mobiland AD 376 213 03 1 -

CASE M.8792 - T-Mobile NL/Tele2 NL

EUROPEAN COMMISSION DG Competition CASE M.8792 - T-Mobile NL/Tele2 NL (Only the English text is authentic) MERGER PROCEDURE REGULATION (EC) 139/2004 Article 8 (1) Regulation (EC) 139/2004 Date: 27/11/2018 This text is made available for information purposes only. A summary of this decision is published in all EU languages in the Official Journal of the European Union. Parts of this text have been edited to ensure that confidential information is not disclosed; those parts are enclosed in square brackets. EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 27.11.2018 C(2018) 7768 final PUBLIC VERSION COMMISSION DECISION of 27.11.2018 declaring a concentration to be compatible with the internal market and the functioning of the EEA Agreement (Case M.8792 - T-Mobile NL/Tele2 NL) (Only the English version is authentic) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................ 11 2. The Parties and the Transaction ................................................................................. 12 3. Union dimension ........................................................................................................ 13 4. The procedure ............................................................................................................. 13 5. The investigation ........................................................................................................ 14 6. The Dutch mobile telecommunications sector .......................................................... -

Download Here

Rewheel research Iliad’s 4th MNO venture into Italy ̶ Will it pay off? Can Iliad make money by charging only €7.99 per subscriber? Rewheel research PRO study,8th January 2019 Iliad Italy profitability margins Iliad Italy payback period Gross profit margin, EBITDA margin, cash flow margin & CAPEX intensity Cumulative cash flow (EBITDA - CAPEX - spectrum fees) Cumulative Cash Flow mln EUR % % of service revenue Gross profit EBITDA Cash Flow (EBITDA-CAPEX-spectrum fees) 993 mln EUR CAPEX intensity spectrum Highlights ̶ Will Iliad achieve an EBITDA break-even with less than 10% market share as it has claimed? ̶ How much will it need to invest to build a mobile network that will put it on similar footing with the other 3 MNOs? ̶ How much more spectrum will Iliad need to buy and by when? ̶ When will Iliad’s operations in Italy turn cash flow positive? ̶ Can Iliad make money by charging only €7.99 per subscriber? ̶ What is the minimum ARPU level that Iliad will need in order to break even in a reasonable period? ̶ Can Iliad break even only with mobile subscribers or will it need to tap into the growing broadband market? ̶ Fixed broadband, wireless broadband, or both? ̶ Should Iliad spend big to buy Fastweb or go solo? Is there a third way? ̶ How long will Iliad’s payback period be in Italy? ̶ How many billions of EUR in revenues will TIM, Vodafone and WindTre shed if Iliad breaks even with a very low ARPU? ̶ Will WindTre follow Three UK’s footsteps and attack the home broadband market head-on with 5G wireless plans? ̶ How far can WindTre go with -

Download Spotlight

SPOTLIGHT Telco Mergers and Acquisitions Strategic Backgrounds, Use Cases and Future Developments This publication or parts there of may only be reproduced or copied with the prior written permission of Detecon International GmbH. Published by Detecon International GmbH. www.detecon.com Strategic Backgrounds, Use Cases and Future Developments I Detecon SPOTLIGHT Content What is it all about? 2 Telco M&A Trends 4 Summary 14 The Authors 15 The Company 16 Footnotes 17 05/2019 1 Detecon SPOTLIGHT I Telco Mergers and Acquisitions What is it all about? For years, we at Detecon have been actively supporting our clients in acquiring and integrating other organizations within the telecommunications industry. Thereby, our consultants have been observing worldwide transaction trends and mergers & acquisitions activities (M&A) in the global telecommunication markets. This “Telco Mergers and Acquisitions Spotlight” will highlight these observations from the past year and provide strategic insights into the most recent market developments, present selected use cases and explain the underlying rationale of those mergers. Finally, it will provide an outlook for possible M&A activities in 2019 and beyond. Mergers and acquisitions can be a valuable lever in building new digital business models or facilitating digital transformation. Furthermore, they are commonly used to generate growth, create synergies and reduce risk through diversification. Hence, it is not surprising that during a time characterized by increasing market uncertainty, the year 2018 has seen fewer transactions than in previous years. However, it was a record year for high-value M&A deals which can be seen in a comparison between 2017 and 2018 (Figure 1: Average deal value ($bn), 3Q17 vs. -

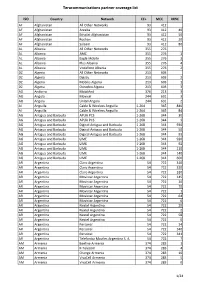

Teracommunications Partner Coverage List

Teracommunications partner coverage list ISO Country Network CC+ MCC MNC AF Afghanistan All Other Networks 93 412 AF Afghanistan Areeba 93 412 40 AF Afghanistan Etisalat Afghanistan 93 412 50 AF Afghanistan Roshan 93 412 20 AF Afghanistan Salaam 93 412 80 AL Albania All Other Networks 355 276 AL Albania AMC 355 276 1 AL Albania Eagle Mobile 355 276 3 AL Albania Plus Albania 355 276 4 AL Albania Vodafone Albania 355 276 2 DZ Algeria All Other Networks 213 603 DZ Algeria Djezzy 213 603 2 DZ Algeria Mobilis Algeria 213 603 1 DZ Algeria Ooredoo Algeria 213 603 3 AD Andorra MobilAnd 376 213 3 AO Angola Movicel 244 631 3 AO Angola Unitel Angola 244 631 2 AI Anguilla Cable & Wireless Anguilla 1-264 365 840 AI Anguilla Cable & Wireless Anguilla 1-264 365 84 AG Antigua and Barbuda APUA PCS 1-268 344 30 AG Antigua and Barbuda APUA PCS 1-268 344 3 AG Antigua and Barbuda Digicel Antigua and Barbuda 1-268 344 930 AG Antigua and Barbuda Digicel Antigua and Barbuda 1-268 344 50 AG Antigua and Barbuda Digicel Antigua and Barbuda 1-268 344 93 AG Antigua and Barbuda LIME 1-268 344 920 AG Antigua and Barbuda LIME 1-268 344 92 AG Antigua and Barbuda LIME 1-268 344 110 AG Antigua and Barbuda LIME 1-268 344 140 AG Antigua and Barbuda LIME 1-268 344 600 AR Argentina Claro Argentina 54 722 310 AR Argentina Claro Argentina 54 722 320 AR Argentina Claro Argentina 54 722 330 AR Argentina Movistar Argentina 54 722 145 AR Argentina Movistar Argentina 54 722 10 AR Argentina Movistar Argentina 54 722 70 AR Argentina Movistar Argentina 54 722 1 AR Argentina Movistar Argentina 54 722 64 AR Argentina Movistar Argentina 54 722 6 AR Argentina Nextel Argentina 54 722 20 AR Argentina Nextel Argentina 54 722 2 AR Argentina Nextel Argentina 54 722 58 AR Argentina Nextel Argentina 54 722 0 AR Argentina Personal 54 722 34 AR Argentina Personal 54 722 340 AR Argentina Personal 54 722 341 AR Argentina Telefonica Moviles Argentina S. -

CASE M.8792 - T-Mobile NL/Tele2 NL

EUROPEAN COMMISSION DG Competition CASE M.8792 - T-Mobile NL/Tele2 NL (Only the English text is authentic) MERGER PROCEDURE REGULATION (EC) 139/2004 Article 8 (1) Regulation (EC) 139/2004 Date: 27/11/2018 This is a provisional non-confidential version. The definitive non- confidential version will be published as soon as it is available. This text is made available for information purposes only. A summary of this decision will be published in all EU languages in the Official Journal of the European Union. Parts of this text have been edited to ensure that confidential information is not disclosed; those parts are enclosed in square brackets. EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 27.11.2018 C(2018) 7768 final PUBLIC VERSION COMMISSION DECISION of 27.11.2018 declaring a concentration to be compatible with the internal market and the functioning of the EEA Agreement (Case M.8792 - T-Mobile NL/Tele2 NL) (Only the English version is authentic) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................ 11 2. The Parties and the Transaction ................................................................................. 12 3. Union dimension ........................................................................................................ 12 4. The procedure ............................................................................................................. 13 5. The investigation ....................................................................................................... -

T-Mobile Netherlands Tele2

ANNOUNCED ACQUISITION OF TELE2 NETHERLANDS BY T-MOBILE NETHERLANDS INVESTOR PRESENTATION DECEMBER 2017 TRANSACTION OVERVIEW – KEY HIGHLIGHTS ✓ T-Mobile Netherlands (T-Mobile) to join forces with Tele2 Netherlands (T2 NL) from Tele2 Group AB (Tele2) o Tele2 to receive €190m cash and a 25% minority stake in the enlarged T-Mobile (on a cash-and-debt-free basis) o Deutsche Telekom to hold 75% (and continue to consolidate T-Mobile) and a €1.1bn intercompany loan receivable from T-Mobile Key Terms o Prior to the completion of the transaction, T-Mobile will spin out in a cash neutral way its mobile tower assets into a separate legal entity (TowerCo) which will not be part of the transaction and will remain in 100% ownership of Deutsche Telekom o TowerCo pro-forma EBITDA of c.€~35m post carve-out ✓ Enlarged company will continue to operate as T-Mobile Netherlands and will also use the Tele2 brand in the market ✓ Creating a strong #3 converged player in the Netherlands telco market with revenues in excess of €2.0bn1 and around 4.3m2 mobile postpaid subscribers Transaction ✓ Enlarged T-Mobile Netherlands will be positioned to compete more effectively against FMC duopoly Rationale ✓ Significant value creation opportunity with c.€150m of annual run-rate cost and capex synergies to be achieved in three years after closing – €1bn+ NPV Timetable ✓ Transaction is subject to approval by the relevant competition authorities and expected to close in H2 2018 1 LTM as of 3Q 17 2 As of 3Q17 - privileged & confidential - 2 RECENT INVESTMENTS POSITIONED T-MOBILE