Transatlantic Translations of the Button-Down Shirt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Alan Bown

Garageland 1-176 COR:Mise en page 1 11/03/09 18:32 Page 1 GARAGELANDMOD, FREAKBEAT, R&B et POP 1964-1968 : LA NAISSANCE DU COOL Garageland 1-176 COR:Mise en page 1 12/03/09 17:44 Page 2 DU MÊME AUTEUR THE SEX PISTOLS, Albin Michel, 1996 OASIS, Venice, 1998 DAVID BOWIE, Librio, 1999 IGGY POP, Librio, 2002 A NikolaAcin, always on my mind Un livre édité par Hervé Desinge Coordination : Annie Pastor © 2009, Éditions Hoëbeke, Paris www.hoebeke.fr Dépôt légal : mai 2009 ISBN : 9782-84230-351-8 Imprimé en Italie Garageland 1-176 COR:Mise en page 1 11/03/09 18:32 Page 3 MOD,GARAGELAND FREAKBEAT, R&B et POP 1964-1968 : LA NAISSANCE DU COOL NICOLAS UNGEMUTH # Garageland 1-176 COR:Mise en page 1 11/03/09 18:32 Page 4 Garageland 1-176 COR:Mise en page 1 11/03/09 18:32 Page 5 Préface parAndrew LoogOldham LES SIXTIES,ou d’ailleurs la fin des années 1940 et les années 1950 apparence profonde et préoccupée par son temps,il n’en était rien : qui les ont inspirées,sont loin d’être achevées.Elles continuent de elle était plus préoccupée par l’argent.L’histoire et en particulier ces miner,déterminer et servir de modèle visuel et sonore à presque tout périodes dominées par le multimédia tout-puissant nous montrent ce qui vaut la peine d’être salué par nos yeux,oreilles,cœur, que (désolé John etYoko) la guerre est loin d’être finie et que troisième œil et cerveau aujourd’hui.Et tout est dans la musique. -

The Mad, Mad World of Niche Sports

By Ruth S. Barrett Th e Mad, Mad World of Niche Sports 74 Where the desperation of late-stage m 1120_WEL_Barrett_TulipMania [Print]_14155638.indd 74 9/22/2020 12:04:44 PM Photo Illustrations by Pelle Cass Among Ivy League– Obsessed Parents meritocracy is so strong, you can smell it 75 1120_WEL_Barrett_TulipMania [Print]_14155638.indd 75 9/22/2020 12:04:46 PM On paper, Sloane, a buoyant, chatty, stay-at-home mom from Faireld County, Connecticut, seems almost unbelievably well prepared to shepherd her three daughters through the roiling world of competitive youth sports. She played tennis and ran track in high school and has an advanced “I thought, What are we doing? ” said Sloane, who asked to be degree in behavioral medicine. She wrote her master’s thesis on the identied by her middle name to protect her daughters’ privacy connection between increased aerobic activity and attention span. and college-recruitment chances. “It’s the Fourth of July. You’re She is also versed in statistics, which comes in handy when she’s ana- in Ohio; I’m in California. What are we doing to our family? lyzing her eldest daughter’s junior-squash rating— and whiteboard- We’re torturing our kids ridiculously. ey’re not succeeding. ing the consequences if she doesn’t step up her game. “She needs We’re using all our resources and emotional bandwidth for at least a 5.0 rating, or she’s going to Ohio State,” Sloane told me. a fool’s folly.” She laughed: “I don’t mean to throw Ohio State under the Yet Sloane found that she didn’t know how to make the folly bus. -

Carnaby History

A / W 1 1 Contents Introduction C S W T S C A RN A BY IS KNO W N FOR UNIQUE INDEPENDENT BOUTIQUES , C ON C EPT STORES , GLOBA L FA SHION C F & D N Q BR A NDS , awa RD W INNING RESTAUR A NTS , ca FÉS A ND BA RS ; M A KING IT ONE OF L ONDON ' S MOST H POPUL A R A ND DISTIN C TIVE SHOPPING A ND LIFESTYLE DESTIN ATIONS . T K C S TEP UNDER THE IC ONIC C A RN A BY A R C H A ND F IND OUT MORE A BOUT THE L ATEST EXPERIEN C E THE C RE ATIVE A ND UNIQUE VIBE . C OLLE C TIONS , EVENTS , NE W STORES , T HE STREETS TH AT M A KE UP THIS STYLE VILL AGE RESTAUR A NTS A ND POP - UP SHOPS AT I F’ P IN C LUDE C A RN A BY S TREET , N E W BURGH S TREET , ca RN A BY . C O . UK . M A RSH A LL S TREET , G A NTON S TREET , K INGLY S TREET , M F OUBERT ’ S P L ac E , B E A K S TREET , B ROA D W IC K S TREET , M A RLBOROUGH C OURT , L O W NDES C OURT , G RE AT M A RLBOROUGH S TREET , L EXINGTON S TREET A ND THE VIBR A NT OPEN A IR C OURTYA RD , K INGLY C OURT . C A RN A BY IS LO caTED JUST MINUTES awaY FROM O XFORD C IR C US A ND P Icca DILLY C IR C US IN THE C ENTRE OF L ONDON ’ S W EST E ND . -

Freak Emporium

Search: go By Artist By Album Title More Options... Home | Search | My Freak Emporium | View Basket | Checkout | Help | Links | Contact | Log In Bands & Artists: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z | What's New | DVDs | Books | Top Sellers Browse Over 120 Genres: Select a genre... 60's & 70's Compilations - Blues (9 Email Me about new products in this genre | More Genres products) > LIST ALL | New See Also: A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Year Offer 60's & 70's Euro Folk Rock 60's & 70's UK Folk Rock 60's & 70's Japanese / Korean / Asian Rock and Pop 60's & 70's Compilations - Pop & Rock Search 60's & 70's Compilations - Blues : go! 60's & 70's Acid Folk & Singer/Songwriter Search Entire Catalogue > 60's & 70's Compilations - Psychedelia 60's & 70's Psychedelia 60's & 70's Compilations - Garage, Beat, Freakbeat, Surf, R&B 60's & 70's Prog Rock 60s Texan Psych And Garage Mod / Freakbeat Latest additions & updates to our catalogue: Paint It Black - Various. CD, £12.00 Blues For Dotsie - Various. CD, £12.00 (Label: EMI, Cat.No: 367 2502) (Label: Ace, Cat.No: CDCHD 1115) Fascinating twenty track Everything from Jump to Down Home to Boogie compilation CD of Rolling Stones Woogie babes on this collection of West Coast covers by some of the greatest Blues cut for and by Dootsie Williams. -

CRISIS of PURPOSE in the IVY LEAGUE the Harvard Presidency of Lawrence Summers and the Context of American Higher Education

Institutions in Crisis CRISIS OF PURPOSE IN THE IVY LEAGUE The Harvard Presidency of Lawrence Summers and the Context of American Higher Education Rebecca Dunning and Anne Sarah Meyers In 2001, Lawrence Summers became the 27th president of Harvard Univer- sity. Five tumultuous years later, he would resign. The popular narrative of Summers’ troubled tenure suggests that a series of verbal indiscretions created a loss of confidence in his leadership, first among faculty, then students, alumni, and finally Harvard’s trustee bodies. From his contentious meeting with the faculty of the African and African American Studies Department shortly af- ter he took office in the summer of 2001, to his widely publicized remarks on the possibility of innate gender differences in mathematical and scientific aptitude, Summers’ reign was marked by a serious of verbal gaffes regularly reported in The Harvard Crimson, The Boston Globe, and The New York Times. The resignation of Lawrence Summers and the sense of crisis at Harvard may have been less about individual personality traits, however, and more about the context in which Summers served. Contestation in the areas of university governance, accountability, and institutional purpose conditioned the context within which Summers’ presidency occurred, influencing his appointment as Harvard’s 27th president, his tumultuous tenure, and his eventual departure. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution - Noncommercial - No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecom- mons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. You may reproduce this work for non-commercial use if you use the entire document and attribute the source: The Kenan Institute for Ethics at Duke University. -

Spotlight Supima

AMERICAN GROWN | SUPERIOR | RARE | AUTHENTIC JUNE 2021 In This Edition Spotlight Supima PAGE 1 Joseph DeAcetis Spotlight Supima Forbes Contributing Editor ---------------------------- Marc Lewkowitz PAGE 2 Supima, President & CEO Weekly Export Summary “SUPIMA is 100% extra-long staple cotton in contrast to other well-known cotton labels such Supima and Albini Challenge as Egyptian or Pima. ® the Next Generation Today, Supima focuses on partnering with of Fashion Designers leading brands across fashion and home markets Gettees to ensure that consumers have access to and Get Cropped receive top quality products.” ---------------------------- PAGE 3 Daddy Dearest hat better way to tell the Father’s Day Guide story of Supima than through ---------------------------- the journalism of Forbes mag- PAGE 4 azine. Supima President and May Licensing Update CEO, Marc Lewkowitz recently sat down for an interview with ForbesW Contributing Editor Joseph DeAcetis. Covering a wide 100% of Supima cotton is mechanically harvested. range of topics from the history of Supima cotton to its unique traceability program, DeAcetis dives into why Supima cotton STAY CONNECTED is considered to be the top 1% of cotton grown around the world and the many relevant issues and challenges in today’s textile industry. America Has One Of The Best Luxury Cotton Grown In Every bale of Supima cotton has its length, The World strength and fineness classed by the USDA. Quite often, I like to highlight the great significance that the United States has on the world of fashion. When you think of all the developments created in our great nation such as the tuxedo, preppy, sportswear and even denim. -

Travels of a Country Woman

Travels of a Country Woman By Lera Knox Travels of a Country Woman Travels of a Country Woman By Lera Knox Edited by Margaret Knox Morgan and Carol Knox Ball Newfound Press THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE LIBRARIES, KNOXVILLE iii Travels of a Country Woman © 2007 by Newfound Press, University of Tennessee Libraries All rights reserved. Newfound Press is a digital imprint of the University of Tennessee Libraries. Its publications are available for non-commercial and educational uses, such as research, teaching and private study. The author has licensed the work under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/>. For all other uses, contact: Newfound Press University of Tennessee Libraries 1015 Volunteer Boulevard Knoxville, TN 37996-1000 www.newfoundpress.utk.edu ISBN-13: 978-0-9797292-1-8 ISBN-10: 0-9797292-1-1 Library of Congress Control Number: 2007934867 Knox, Lera, 1896- Travels of a country woman / by Lera Knox ; edited by Margaret Knox Morgan and Carol Knox Ball. xiv, 558 p. : ill ; 23 cm. 1. Knox, Lera, 1896- —Travel—Anecdotes. 2. Women journalists— Tennessee, Middle—Travel—Anecdotes. 3. Farmers’ spouses—Tennessee, Middle—Travel—Anecdotes. I. Morgan, Margaret Knox. II. Ball, Carol Knox. III. Title. PN4874 .K624 A25 2007 Book design by Martha Rudolph iv Dedicated to the Grandchildren Carol, Nancy, Susy, John Jr. v vi Contents Preface . ix A Note from the Newfound Press . xiii part I: The Chicago World’s Fair. 1 part II: Westward, Ho! . 89 part III: Country Woman Goes to Europe . -

Board Stands Pat on Supervisor's Transfer

«„.*» ^ -j^-gH ted; cf spiritually - enough. It Him urn nflarsY snrtilmltsilim 'pot dMtoUor factor ID the CfcrMtaa 8dtJK» Is ftrtng the arr spiritual ondetstanding to ov- e this tear mod thereby to «nd Ml satisfaction can he attained after mean* satisfaction to ev- here present sod In the world I* II mtani'sstlsfartlnn I Vol. !tail of existence through the SI CRANFORD, N~J.r i»y iuid IVIIW msii ttt^n of the FIVE CENfS cil truth taught to the Science lection, Christian Science. • Aimoonc* Honor Ptipik Baby Frank Caruso In Crmaford Hifh School snan Hartley CSNTBAL sUtLKT ' COMaUTTBs: Board Stands Pat on Wifls Popularity Vote - Following Is the hifh school honor Will Speak at Rally ' BiUmatcd needs ...,..r»,000.00 roll for the fifth marking period: CwilrlbaUofu Clubs and organisations. I1.M0J7 Betty Di Tullio and Ditzel Frethmeo—Oair» Weir, Otrtrude County and Local Candidate* Supervisor's Transfer Cremerlus,. Oortnne Johnson. Betty IndWduaU , 598.S0 Twin. Rank Next. Needy Will Also Be Heard at Relief Enterprlsea MliOO WiU Share in Winner'. Munio. Henrietta Miller. Betty Low- sjurttaa" land. Frederick Kfcoori, Harriet Nick. Meeting Monday Night ";. .total 1 '_ UZlim doud Claims No Funds Citizens Register Vigorous Prizes. —-'— . ' / Miner Wetmort. Eugerw HenrtahcPor- Ekctnkeen Process othy Dtller, Helen Norgard. Lucy Tails- Cleveland School. „ EipdMIUres To Pay for New Job Protest, But School Offi- i-llS* ' ' ' Frank Caruso, three year old ton of feiro, MoUle. Comsiock, laabelle Frank, Investigation and super- . dais. Refuse to Rescind CKANVOKO, N. J. Officer and Mrs. Rani; Canuo of S3 Mary Tinness. Helen Bemlwim. Phyl- Congresman Fred A. -

Put on Your Boots and Harrington!': the Ordinariness of 1970S UK Punk

Citation for the published version: Weiner, N 2018, '‘Put on your boots and Harrington!’: The ordinariness of 1970s UK punk dress' Punk & Post-Punk, vol 7, no. 2, pp. 181-202. DOI: 10.1386/punk.7.2.181_1 Document Version: Accepted Version Link to the final published version available at the publisher: https://doi.org/10.1386/punk.7.2.181_1 ©Intellect 2018. All rights reserved. General rights Copyright© and Moral Rights for the publications made accessible on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Please check the manuscript for details of any other licences that may have been applied and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. You may not engage in further distribution of the material for any profitmaking activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute both the url (http://uhra.herts.ac.uk/) and the content of this paper for research or private study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, any such items will be temporarily removed from the repository pending investigation. Enquiries Please contact University of Hertfordshire Research & Scholarly Communications for any enquiries at [email protected] 1 ‘Put on Your Boots and Harrington!’: The ordinariness of 1970s UK punk dress Nathaniel Weiner, University of the Arts London Abstract In 2013, the Metropolitan Museum hosted an exhibition of punk-inspired fashion entitled Punk: Chaos to Couture. -

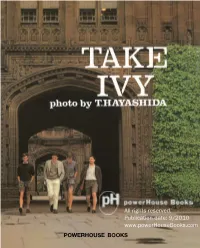

Take Ivy Was Originally Published Shosuke Ishizu Is the Representative Director in Japan in 1965, Setting Off an Explosion of of Ishizu Office

Teruyoshi Hayashida was born in the fashionable Aoyama District of Tokyo, where he also grew up. He began shooting cover images for Men’s Club magazine after the title’s launch. A sophisticated Photographs by Teruyoshi Hayashida dresser and a connoisseur of gourmet food, Text by Shosuke Ishizu, Toshiyuki Kurosu, he is known for his homemade, soy-sauce- and Hajime (Paul) Hasegawa marinated Japanese pepper (sansho), and his love of gunnel tempura and Riesling wine. Described by The New York Times as, “a treasure of fashion insiders,” Take Ivy was originally published Shosuke Ishizu is the representative director in Japan in 1965, setting off an explosion of of Ishizu Office. Originally born in Okayama American-influenced “Ivy Style” fashion among Prefecture, after graduating from Kuwasawa Design students in the trendy Ginza shopping district School he worked in the editorial division at Men’s of Tokyo. The product of four collegiate style Club until 1960 when he joined VAN Jacket Inc. enthusiasts, Take Ivy is a collection of candid He established Ishizu Office in 1983, and now photographs shot on the campuses of America’s produces several brands including Niblick. elite, Ivy League universities. The series focuses on men and their clothes, perfectly encapsulating Toshiyuki Kurosu was raised in Tokyo. He joined the unique student fashion of the era. Whether VAN Jacket Inc. in 1961, where he was responsible lounging in the quad, studying in the library, riding for the development of merchandise and sales bikes, in class, or at the boathouse, the subjects of promotion. He left the company in 1970 and Take Ivy are impeccably and distinctively dressed in started his own business, Cross and Simon. -

“THE IVY LOOK POCKET GUIDE” Interview by GSTAG

“THE IVY LOOK POCKET GUIDE” Interview by GSTAG. 1) Could you please introduce yourself? JP Gall: JP Gall, modernist, flaneur, salesman and author. Graham Marsh: Graham Marsh is an art director, illustrator and author. He never wears double breasted jackets or black shoes. 2) How did you both come to The Ivy Look? G.M.: As I said in the book, Ivy clothes were addictive. I got hooked the first time I saw them being worn by the pilgrims of modern jazz who inhabited the London based art Department of Marvel Comics where I first worked back in the early 1960s. It was an insider’s world of narrow lapelled sharp Ivy suits, narrow knitted ties and narrow haircuts. The soundtrack to this cool, detached world included the music of Miles Davis, Gerry Mulligan and Jimmy Smith. This was a world I wanted into and like a sponge proceeded to soak up all it had to offer. JP.G.: I made a concerted effort to be different from my peers. I was a teenager in the 1980s and I felt completely disconnected from the music and fashion of that period. It left me cold. I thank 2 people. Firstly Paul Weller who made me a mod, because from there it was a process of curiosity and research that led me on from elementary mod to the whole Ivy League thing. And I also need to thank John Simons, a mentor for many of us kids keen to get the feel of the original Ivy League jazz culture under our finger nails. -

When the War Ended in 1945, Europe Turned to the Task of Rebuilding, and Americans Once Again Looked West for Inspiration

When the war ended in 1945, Europe turned to the task of rebuilding, and Americans once again looked west for inspiration. The swagger of the cowboy fitted the victorious mood of the country. Dude ranches were now a destination for even the middle class. Hopalong Cassidy and the puppet cowboy Howdy Doody kept children glued to their televisions, and Nashville’s country music industry produced one ‘rhinestone cowboy’ after another. Westerns were also one of the most popular film genres. As the movie director Dore Schary noted, ‘the American movie screen was dominated by strong, rugged males – the “one punch, one [gun] shot variety”.’43 In this milieu, cowboy boots became increasingly glamorous. Exagger- atedly pointed toes, high-keyed coloured leathers, elaborate appliqué and even actual rhinestone embellishments were not considered excessive. This period has been called the golden age of cowboy boots, and the artistry and imagination expressed in late 1940s and 1950s boot-making is staggering. The cowboy boot was becoming part of costume, a means of dressing up, of playing type. This point was made clear by the popularity of dress-up cowboy clothes, including boots, for children. Indeed, this transformation into costume was becoming the fate of many boots in fashion. Although most boot styles fell out of fashion in the 1950s, in the immediate post-war period a particular form of military footwear did pass into men’s stylish casual dress: the chukka boot, said to have come from India, and its variant, the desert boot. Designed as a low ankle boot with a two to three eyelet closure, chukkas were said to have been worn for comfort by British polo players both on and off the field in India.44 The simple desert boot was based on the traditional chukka but in Cairo during the war it was given a crepe sole and soft suede upper.