Nostalgia and Representations of Mod in Quadrophenia and Absolute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Alan Bown

Garageland 1-176 COR:Mise en page 1 11/03/09 18:32 Page 1 GARAGELANDMOD, FREAKBEAT, R&B et POP 1964-1968 : LA NAISSANCE DU COOL Garageland 1-176 COR:Mise en page 1 12/03/09 17:44 Page 2 DU MÊME AUTEUR THE SEX PISTOLS, Albin Michel, 1996 OASIS, Venice, 1998 DAVID BOWIE, Librio, 1999 IGGY POP, Librio, 2002 A NikolaAcin, always on my mind Un livre édité par Hervé Desinge Coordination : Annie Pastor © 2009, Éditions Hoëbeke, Paris www.hoebeke.fr Dépôt légal : mai 2009 ISBN : 9782-84230-351-8 Imprimé en Italie Garageland 1-176 COR:Mise en page 1 11/03/09 18:32 Page 3 MOD,GARAGELAND FREAKBEAT, R&B et POP 1964-1968 : LA NAISSANCE DU COOL NICOLAS UNGEMUTH # Garageland 1-176 COR:Mise en page 1 11/03/09 18:32 Page 4 Garageland 1-176 COR:Mise en page 1 11/03/09 18:32 Page 5 Préface parAndrew LoogOldham LES SIXTIES,ou d’ailleurs la fin des années 1940 et les années 1950 apparence profonde et préoccupée par son temps,il n’en était rien : qui les ont inspirées,sont loin d’être achevées.Elles continuent de elle était plus préoccupée par l’argent.L’histoire et en particulier ces miner,déterminer et servir de modèle visuel et sonore à presque tout périodes dominées par le multimédia tout-puissant nous montrent ce qui vaut la peine d’être salué par nos yeux,oreilles,cœur, que (désolé John etYoko) la guerre est loin d’être finie et que troisième œil et cerveau aujourd’hui.Et tout est dans la musique. -

1 Tennessee Track & Field Record Book » Utsports

TENNESSEE TRACK & FIELD RECORD BOOK » UTSPORTS.COM » @VOL_TRACK 1 TRACK & FIELD RECORD BOOK TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION ALL-TIME ROSTER/LETTERMEN Table of Contents/Credits 1 All-Time Women’s Roster 52-54 Quick Facts 2 All-Time Men’s Lettermen 55-58 Media Information 2 2017 Roster 3 YEAR-BY-YEAR 1933-1962 59 COACHING HISTORY 1963-1966 60 All-Time Women’s Head Coaches 4 1967-1969 61 All-Time Men’s Head Coaches 5-6 1970-1972 62 1973-1975 63 NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS 1976-1978 64 Women’s Team National Championships 7-8 1979-1981 65 Men’s Team National Championships 9-10 1981-1982 66 All-Time National Champions Leaderboard 11 1983-1984 67 Women’s Individual National Champions 12 1984-1985 68 Men’s Individual National Champions 13 1986-1987 69 1987-1988 70 THE SEC 1989-1990 71 Tennessee’s SEC Title Leaders 14 1990-1991 72 UT’s SEC Team Championships 14 1992-1993 73 All-Time Women’s SEC Indoor Champions 15 1993-1994 74 All-Time Women’s SEC Outdoor Champions 16 1995-1996 75 All-Time Men’s SEC Indoor Champions 17 1996-1997 76 All-Time Men’s SEC Outdoor Champions 18-19 1998-1999 77 1999-2000 78 ALL-AMERICANS 2001-2002 79 All-American Leaderboard 20 2002-2003 80 Women’s All-Americans 21-24 2004-2005 81 Men’s All-Americans 25-29 2005-2006 82 2007-2008 83 TENNESSEE OLYMPIANS 2008-2009 84 Olympians By Year 30-31 2010-2011 85 Medal Count 31 2011-2012 86 2013-2014 87 SCHOOL RECORDS/TOP TIMES LISTS 2014-2015 88 School Records 32 2016-2017 89 Freshman Records 33 2017 90 Women’s Top Indoor Marks 34 Women’s Top Outdoor Marks 35 FACILITIES & RECORDS -

Freak Emporium

Search: go By Artist By Album Title More Options... Home | Search | My Freak Emporium | View Basket | Checkout | Help | Links | Contact | Log In Bands & Artists: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z | What's New | DVDs | Books | Top Sellers Browse Over 120 Genres: Select a genre... 60's & 70's Compilations - Blues (9 Email Me about new products in this genre | More Genres products) > LIST ALL | New See Also: A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Year Offer 60's & 70's Euro Folk Rock 60's & 70's UK Folk Rock 60's & 70's Japanese / Korean / Asian Rock and Pop 60's & 70's Compilations - Pop & Rock Search 60's & 70's Compilations - Blues : go! 60's & 70's Acid Folk & Singer/Songwriter Search Entire Catalogue > 60's & 70's Compilations - Psychedelia 60's & 70's Psychedelia 60's & 70's Compilations - Garage, Beat, Freakbeat, Surf, R&B 60's & 70's Prog Rock 60s Texan Psych And Garage Mod / Freakbeat Latest additions & updates to our catalogue: Paint It Black - Various. CD, £12.00 Blues For Dotsie - Various. CD, £12.00 (Label: EMI, Cat.No: 367 2502) (Label: Ace, Cat.No: CDCHD 1115) Fascinating twenty track Everything from Jump to Down Home to Boogie compilation CD of Rolling Stones Woogie babes on this collection of West Coast covers by some of the greatest Blues cut for and by Dootsie Williams. -

Vinyl Theory

Vinyl Theory Jeffrey R. Di Leo Copyright © 2020 by Jefrey R. Di Leo Lever Press (leverpress.org) is a publisher of pathbreaking scholarship. Supported by a consortium of liberal arts institutions focused on, and renowned for, excellence in both research and teaching, our press is grounded on three essential commitments: to publish rich media digital books simultaneously available in print, to be a peer-reviewed, open access press that charges no fees to either authors or their institutions, and to be a press aligned with the ethos and mission of liberal arts colleges. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. The complete manuscript of this work was subjected to a partly closed (“single blind”) review process. For more information, please see our Peer Review Commitments and Guidelines at https://www.leverpress.org/peerreview DOI: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11676127 Print ISBN: 978-1-64315-015-4 Open access ISBN: 978-1-64315-016-1 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019954611 Published in the United States of America by Lever Press, in partnership with Amherst College Press and Michigan Publishing Without music, life would be an error. —Friedrich Nietzsche The preservation of music in records reminds one of canned food. —Theodor W. Adorno Contents Member Institution Acknowledgments vii Preface 1 1. Late Capitalism on Vinyl 11 2. The Curve of the Needle 37 3. -

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020 1 REGA PLANAR 3 TURNTABLE. A Rega Planar 3 8 ASSORTED INDIE/PUNK MEMORABILIA. turntable with Pro-Ject Phono box. £200.00 - Approximately 140 items to include: a Morrissey £300.00 Suedehead cassette tape (TCPOP 1618), a ticket 2 TECHNICS. Five items to include a Technics for Joe Strummer & Mescaleros at M.E.N. in Graphic Equalizer SH-8038, a Technics Stereo 2000, The Beta Band The Three E.P.'s set of 3 Cassette Deck RS-BX707, a Technics CD Player symbol window stickers, Lou Reed Fan Club SL-PG500A CD Player, a Columbia phonograph promotional sticker, Rock 'N' Roll Comics: R.E.M., player and a Sharp CP-304 speaker. £50.00 - Freak Brothers comic, a Mercenary Skank 1982 £80.00 A4 poster, a set of Kevin Cummins Archive 1: Liverpool postcards, some promo photographs to 3 ROKSAN XERXES TURNTABLE. A Roksan include: The Wedding Present, Teenage Fanclub, Xerxes turntable with Artemis tonearm. Includes The Grids, Flaming Lips, Lemonheads, all composite parts as issued, in original Therapy?The Wildhearts, The Playn Jayn, Ween, packaging and box. £500.00 - £800.00 72 repro Stone Roses/Inspiral Carpets 4 TECHNICS SU-8099K. A Technics Stereo photographs, a Global Underground promo pack Integrated Amplifier with cables. From the (luggage tag, sweets, soap, keyring bottle opener collection of former 10CC manager and music etc.), a Michael Jackson standee, a Universal industry veteran Ric Dixon - this is possibly a Studios Bates Motel promo shower cap, a prototype or one off model, with no information on Radiohead 'Meeting People Is Easy 10 Min Clip this specific serial number available. -

Put on Your Boots and Harrington!': the Ordinariness of 1970S UK Punk

Citation for the published version: Weiner, N 2018, '‘Put on your boots and Harrington!’: The ordinariness of 1970s UK punk dress' Punk & Post-Punk, vol 7, no. 2, pp. 181-202. DOI: 10.1386/punk.7.2.181_1 Document Version: Accepted Version Link to the final published version available at the publisher: https://doi.org/10.1386/punk.7.2.181_1 ©Intellect 2018. All rights reserved. General rights Copyright© and Moral Rights for the publications made accessible on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Please check the manuscript for details of any other licences that may have been applied and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. You may not engage in further distribution of the material for any profitmaking activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute both the url (http://uhra.herts.ac.uk/) and the content of this paper for research or private study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, any such items will be temporarily removed from the repository pending investigation. Enquiries Please contact University of Hertfordshire Research & Scholarly Communications for any enquiries at [email protected] 1 ‘Put on Your Boots and Harrington!’: The ordinariness of 1970s UK punk dress Nathaniel Weiner, University of the Arts London Abstract In 2013, the Metropolitan Museum hosted an exhibition of punk-inspired fashion entitled Punk: Chaos to Couture. -

Batteriezuordnung Zweirad

Batterie Fahrzeug Type ccm Jahr Batterie ATU-Nr. ATU-Nr. alternativ ADLER M 100 100 B39-6 IC3735 ADLER M 250 250 B39-6 IC3735 ADLER MB 250 250 6N11A-1B ADLY All 50cc models 50 YB4L-B IC3713 SLA12-4 IC3757 AERMACCHI 125 SX 125 12N7-3B KC6695 YB7L-B KC6695 AERMACCHI 175 SX 175 12N7-3B KC6695 YB7L-B KC6695 AERMACCHI 250 Ala Azzurra 250 6N11A-1B AERMACCHI 250 Bianca 250 6N11A-1B AERMACCHI 250 Chimera 250 B39-6 IC3735 AERMACCHI 350 Ala 350 6N11A-1B AERMACCHI 350 Ala Azzurra 350 6N11A-1B AERMACCHI 350 Bianca 350 6N11A-1B AERMACCHI 350 Oro 350 6N11A-1B AERMACCHI 350 Rossa 350 6N11A-1B AERMACCHI 350 Verde 350 6N11A-1B APRILIA AF-1 50 YB4L-B IC3713 SLA12-4 IC3757 APRILIA AF-1 125 Europa 125 YB9B IC3719 12N9-4B-1 APRILIA AF-1 125 Futura 125 91-92 YB9B IC3719 12N9-4B-1 APRILIA AF-1 125 Project 125 -94 YB9B IC3719 12N9-4B-1 APRILIA AF-1 125 Replica 125 -92 12N5,5-3B IC3710 APRILIA Amico (All models) 50 90- YB4L-B IC3713 SLA12-4 IC3757 APRILIA API 50 91-92 YB4L-B IC3713 SLA12-4 IC3757 APRILIA Area 51 50 YB4L-B IC3713 SLA12-4 IC3757 APRILIA AS 125 R 125 12N5,5-3B IC3710 APRILIA Atlantic 125 -08 YB12AL-A KC6694 YB12AL-A2 APRILIA Atlantic Sprint 500 YB14L-B2 IC3729 APRILIA Classic 50 93-97 YB4L-B IC3713 SLA12-4 IC3757 APRILIA Classic 125 YB9B IC3719 12N9-4B-1 IC3719 APRILIA Custome 125 YB4L-B IC3713 SLA12-4 IC3757 APRILIA ET 50 84- YB4L-B IC3713 SLA12-4 IC3757 APRILIA ETV Capo Nord 1000 02- YTX14-BS IC3723 SLA12-12 IC3762 APRILIA ETX 125 Electric Start 125 YB9B IC3719 12N9-4B-1 IC3719 APRILIA ETX 125 Kick Start 125 12N5,5-3B IC3710 APRILIA ETX 250 Electric -

When the War Ended in 1945, Europe Turned to the Task of Rebuilding, and Americans Once Again Looked West for Inspiration

When the war ended in 1945, Europe turned to the task of rebuilding, and Americans once again looked west for inspiration. The swagger of the cowboy fitted the victorious mood of the country. Dude ranches were now a destination for even the middle class. Hopalong Cassidy and the puppet cowboy Howdy Doody kept children glued to their televisions, and Nashville’s country music industry produced one ‘rhinestone cowboy’ after another. Westerns were also one of the most popular film genres. As the movie director Dore Schary noted, ‘the American movie screen was dominated by strong, rugged males – the “one punch, one [gun] shot variety”.’43 In this milieu, cowboy boots became increasingly glamorous. Exagger- atedly pointed toes, high-keyed coloured leathers, elaborate appliqué and even actual rhinestone embellishments were not considered excessive. This period has been called the golden age of cowboy boots, and the artistry and imagination expressed in late 1940s and 1950s boot-making is staggering. The cowboy boot was becoming part of costume, a means of dressing up, of playing type. This point was made clear by the popularity of dress-up cowboy clothes, including boots, for children. Indeed, this transformation into costume was becoming the fate of many boots in fashion. Although most boot styles fell out of fashion in the 1950s, in the immediate post-war period a particular form of military footwear did pass into men’s stylish casual dress: the chukka boot, said to have come from India, and its variant, the desert boot. Designed as a low ankle boot with a two to three eyelet closure, chukkas were said to have been worn for comfort by British polo players both on and off the field in India.44 The simple desert boot was based on the traditional chukka but in Cairo during the war it was given a crepe sole and soft suede upper. -

Vespa Range Brochure3

Technical Specifications Vespa TECHNOLOGY AND POWER 150cc Engine Power 7.4 kW @ 6750 rpm and Torque 10.9Nm @ 5000 rpm. 3 Valve, Aluminium Cylinder Head, Overhead Cam And Roller Rocker Arm, Map Sensing and Variable Spark Timing Management. Engine Also available in 125cc Engine Power 7.1 kW @ 7250 rpm and Torque 9.9Nm @ 6250 rpm. 3 Valve, Aluminium Cylinder Head, Overhead Cam and Roller Rocker Arm, MAP Sensing and Variable Spark Timing Management. Transmission Continuous Variable Transmission. Body Construction Monocoque Full-Steel Body Construction. Overall Dimensions (LxBxH) - 1770 x 690 x 1140. Aircraft derived single side arm Front Suspension with Anti-Dive characteristics. Suspension Rear suspension with Dual-Effect Hydraulic Shock Absorber. Electricals 3 - Phase Electrical System and auto ignition. SAFETY For SXL and VXL : 200 mm Ventilated Front Disc Brake and 140 mm Rear Drum Brake. Brakes For LX and Notte : 150 mm Front Drum Brake and 140 mm Rear Drum Brake. For SXL and VXL : Broader Tubeless Tyres With Front Tyre Size 110/70-11" and Tyres Rear Tyre Size 120/70-10". For LX and Notte : Broader Tube Tyres With Front and Rear Tyre Size 90/100-10". Link spring mechanism between engine and frame provide amazing balance by balancing Stability of mechanical trail and the stabilizing torque which offers low speed balance, accurate steering and high speed stability. CBS Combined Braking System introduced in 125cc models. ABS Anti-Lock Braking System introduced in 150cc models. Connectivity Optional Follow us on twitter.com/Vespa_in | Find us on facebook.com/vespaindia | SMS ‘vespa’ to 56677 | Toll free 18001088784 Features and specifications may differ from those shown and listed here. -

Vespa Turns 75

THIS MAGAZINE HAS BEEN TREATED See Inside !"# "$# !#%% "&'"(#) %&*%#*(+&,%&* -$+)% WITH AN ANTIMICROBIAL PROCESS JANUARY 2021 ON THE HORIZON 21 travel trends that Olympic gold medalist Lindsey will shape the Vonn in Park SPICE year ahead City, Utah WORLD Brooklyn’s hot sauce sommelier INTRODUCING+ THE NEW AMERICAN WAY EN ESPAÑOL Ski Towns An Olympians’ guide to Park City, Sun Valley and Steamboat Springs AMERICANWAY.COM 001_AW_Cover_ESPANOL_v1a.indd 1 11/12/2020 09:31 TOP MODELS VESPA !"# FLESSIBLE This distinctly waspish early model propelled the scooter to fame in Roman Holiday, the black-and- white classic in which Audrey Hepburn and Gregory Peck explore the Eternal City aboard his Vespa Flessible. WOULD YOU BELIEVE? THE AMAZING RACE In 1980, two modified Vespa PX200E scooters piloted by French riders Bernard Tcherniavsky and Marc Simonot crossed the Sahara Desert—and the finish line—for the most arduous motor race in the world: the Paris-Dakar Rally. PINUP 8 BEAUTY Between 1951 and 2005, Vespa produced an This easy rider annual pinup calendar with swimsuit-clad, stiletto-heeled beauties looks good for 75 styled by Italian The iconic Vespa scooter celebrates illustrator Franco its diamond anniversary this year Mosca. “#$ %&&'( %#') * +*(,-” *#.,%*/) best-selling scooter has been a manufacturer Enrico Piaggio stylistic trendse0er—from exclaimed in 1946, noting the England’s 1960s mod culture to rounded and tapered rear end of dozens of Hollywood 1lms. The aeronautical engineer Corradino Italian icon turns 75 this year, a2er DAscanio’s design for a prototype the production of more than 160 scooter. Thus, the versatile Vespa models and 19 million units. The (Italian for “wasp”) was christened. -

Youth Activist Toolkit Credits

YOUTH ACTIVIST TOOLKIT CREDITS Written by: Julia Reticker-Flynn Renee Gasch Director, Youth Organizing & Mobilization Julia Reticker-Flynn Advocates for Youth Contributing writers: Kinjo Kiema Clarissa Brooks Manager of State and Local Campaigns Sydney Kesler Advocates For Youth Madelynn Bovasso Nimrat Brar Locsi Ferra Head of Impact Design & Illustrations: Level Forward Arlene Basillio Contributing Artwork: AMPLIFIER Special thanks to AMPLIFIER, Cleo Barnett, and Alixandra Pimentel for their support and input. This guide was created by Advocates for Youth and Level Forward, and is inspired by the film AMERICAN WOMAN. Advocates for Youth partners with youth leaders, adult allies, and youth-serving organizations to advocate for policies and champion programs that recognize young people’s rights to honest sexual health information; accessible, confidential, and affordable sexual health services; and the resources and opportunities necessary to create sexual health equity for all youth. https://advocatesforyouth.org Level Forward develops, produces and finances entertainment with Oscar, Emmy and Tony-winning producers, working to extend the influence and opportunity of creative excellence and support new voices. We take great responsibility for our work, using film, television, digital and live media to address inequality through story-driven, impact-minded properties. https://www.levelforward.co/ AMERICAN WOMAN is a film that raises questions about power: who has it and who doesn’t, and how best to change that. It challenges us to question the ways people wield power, grapples with the choices presented to both the powerful and the marginalized. The story’s center is a young pacifist whose violent activism has sent her on the run from the law, and who is wrestling with her choices as she joins a cohort of young radicals and their kidnapped convert. -

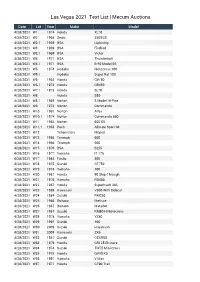

Las Vegas 2021 Text List | Mecum Auctions

Las Vegas 2021 Text List | Mecum Auctions Date Lot Year Make Model 4/28/2021 W1 1974 Honda XL70 4/28/2021 W2 1968 Sears 250SGS 4/28/2021 W2.1 1969 BSA Lightning 4/28/2021 W3 1969 BSA Firebird 4/28/2021 W3.1 1969 BSA Victor 4/28/2021 W4 1971 BSA Thunderbolt 4/28/2021 W4.1 1971 BSA B-50 Model SS 4/28/2021 W5 1974 Hodaka Motocross 100 4/28/2021 W5.1 Hodaka Super Rat 100 4/28/2021 W6 1964 Honda CB750 4/28/2021 W6.1 1973 Honda CB450 4/28/2021 W7.1 1973 Honda SL70 4/28/2021 W8 Honda S90 4/28/2021 W8.1 1969 Norton S Model Hi-Pipe 4/28/2021 W9 1973 Norton Commando 4/28/2021 W10 1967 Norton Atlas 4/28/2021 W10.1 1974 Norton Commando 850 4/28/2021 W11 1962 Norton 650 SS 4/28/2021 W11.1 1963 Puch Allstate Sport 60 4/28/2021 W12 Teliamotors Moped 4/28/2021 W13 1956 Triumph 650 4/28/2021 W14 1966 Triumph 500 4/28/2021 W15 1970 BSA B255 4/28/2021 W16 1977 Yamaha IT 175 4/28/2021 W17 1984 Fantic 300 4/28/2021 W18 1975 Suzuki GT750 4/28/2021 W19 1974 Yamaha 100 4/28/2021 W20 1967 Honda 90 Step-Through 4/28/2021 W21 1976 Yamaha RD400 4/28/2021 W22 1967 Honda Superhawk 305 4/28/2021 W23 1999 Kawasaki V800 With Sidecar 4/28/2021 W24 1984 Suzuki RM250 4/28/2021 W25 1966 Bultaco Metisse 4/28/2021 W26 1967 Bultaco Matador 4/28/2021 W27 1987 Suzuki RM80 H Motocross 4/28/2021 W28 1978 Yamaha YZ80 4/28/2021 W29 1994 Suzuki 400 4/28/2021 W30 2009 Suzuki Hayabusa 4/28/2021 W31 2009 Kawasaki ZX6 4/28/2021 W32 1987 Suzuki GSXR50 4/28/2021 W33 1979 Honda CR125 Elsinore 4/28/2021 W34 1974 Suzuki TM75 Mini-Cross 4/28/2021 W35 1975 Honda QA50 K3 4/28/2021 W36 1997 Yamaha