The Working-Class and Post-War Britain in Pete Townshend's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chris Billam-Smith

MEET THE TEAM George McMillan Editor-in-Chief [email protected] Remembrance day this year marks 100 years since the end of World War One, it is a time when we remember those who have given their lives fighting in the armed forces. Our features section in this edition has a great piece on everything you need to know about the day and how to pay your respects. Elsewhere in the magazine you can find interviews with The Undateables star Daniel Wakeford, noughties legend Basshunter and local boxer Chris Billam Smith who is now prepping for his Commonwealth title fight. Have a spooky Halloween and we’ll see you at Christmas for the next edition of Nerve Magazine! Ryan Evans Aakash Bhatia Zlatna Nedev Design & Deputy Editor Features Editor Fashion & Lifestyle Editor [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Silva Chege Claire Boad Jonathan Nagioff Debates Editor Entertainment Editor Sports Editor [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 3 ISSUE 2 | OCTOBER 2018 | HALLOWEEN EDITION FEATURES 6 @nervemagazinebu Remembrance Day: 100 years 7 A whitewashed Hollywood 10 CONTENTS /Nerve Now My personal experience as an art model 13 CONTRIBUTORS FEATURES FASHION & LIFESTYLE 18 Danielle Werner Top tips for stress-free skin 19 Aakash Bhatia Paris Fashion Week 20 World’s most boring Halloween costumes 22 FASHION & LIFESTYLE Best fake tanning products 24 Clare Stephenson Gracie Leader DEBATES 26 Stephanie Lambert Zlatna Nedev Black culture in UK music 27 DESIGN Do we need a second Brexit vote? 30 DEBATES Ryan Evans Latin America refugee crisis 34 Ella Smith George McMillan Hannah Craven Jake Carter TWEETS FROM THE STREETS 36 Silva Chege James Harris ENTERTAINMENT 40 ENTERTAINMENT 7 Emma Reynolds The Daniel Wakeford Experience 41 George McMillan REMEMBERING 100 YEARS Basshunter: No. -

View Or Download Full Colour Catalogue May 2021

VIEW OR DOWNLOAD FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE 1986 — 2021 CELEBRATING 35 YEARS Ian Green - Elaine Sunter Managing Director Accounts, Royalties & Promotion & Promotion. ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Orders & General Enquiries To:- Tel (0)1875 814155 email - [email protected] • Website – www.greentrax.com GREENTRAX RECORDINGS LIMITED Cockenzie Business Centre Edinburgh Road, Cockenzie, East Lothian Scotland EH32 0XL tel : 01875 814155 / fax : 01875 813545 THIS IS OUR DOWNLOAD AND VIEW FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE FOR DETAILS OF AVAILABILITY AND ON WHICH FORMATS (CD AND OR DOWNLOAD/STREAMING) SEE OUR DOWNLOAD TEXT (NUMERICAL LIST) CATALOGUE (BELOW). AWARDS AND HONOURS BESTOWED ON GREENTRAX RECORDINGS AND Dr IAN GREEN Honorary Degree of Doctorate of Music from the Royal Conservatoire, Glasgow (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – The Hamish Henderson Award for Services to Traditional Music (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – Hall of Fame (Ian Green) East Lothian Business Annual Achievement Award For Good Business Practises (Greentrax Recordings) Midlothian and East Lothian Chamber of Commerce – Local Business Hero Award (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Hands Up For Trad – Landmark Award (Greentrax Recordings) Featured on Scottish Television’s ‘Artery’ Series (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Honorary Member of The Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland and Haddington Pipe Band (Ian Green) ‘Fuzz to Folk – Trax of My Life’ – Biography of Ian Green Published by Luath Press. Music Type Groups : Traditional & Contemporary, Instrumental -

Issues of Image and Performance in the Beatles' Films

“All I’ve got to do is Act Naturally”: Issues of Image and Performance in the Beatles’ Films Submitted by Stephanie Anne Piotrowski, AHEA, to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English (Film Studies), 01 October 2008. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which in not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (signed)…………Stephanie Piotrowski ……………… Piotrowski 2 Abstract In this thesis, I examine the Beatles’ five feature films in order to argue how undermining generic convention and manipulating performance codes allowed the band to control their relationship with their audience and to gain autonomy over their output. Drawing from P. David Marshall’s work on defining performance codes from the music, film, and television industries, I examine film form and style to illustrate how the Beatles’ filmmakers used these codes in different combinations from previous pop and classical musicals in order to illicit certain responses from the audience. In doing so, the role of the audience from passive viewer to active participant changed the way musicians used film to communicate with their fans. I also consider how the Beatles’ image changed throughout their career as reflected in their films as a way of charting the band’s journey from pop stars to musicians, while also considering the social and cultural factors represented in the band’s image. -

Im Auftrag: Medienagentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 040-5149 1465 [email protected]

im Auftrag: medienAgentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 040-5149 1465 [email protected] The Kinks At The BBC (Box – lim. Import) VÖ: 14. August 2012 CD1 10. I'm A Lover, Not A Fighter - Saturday Club - Piccadilly Studios, 1964 1. Interview: Meet The Kinks ' Saturday Club 11. Interview: Ray Talks About The USA ' -The Playhouse Theatre, 1964 Saturday Club - Piccadilly Studios, 1964 2. Cadillac ' Saturday Club - The Playhouse 12. I've Got That Feeling ' Saturday Club - Theatre, 1964 Piccadilly Studios, 1964 3. Interview: Ray Talks About 'You Really Got 13. All Day And All Of The Night ' Saturday Club Me' ' Saturday Club The Playhouse Theatre, - Piccadilly Studios, 1964 1964 14. You Shouldn't Be Sad ' Saturday Club - 4. You Really Got Me ' Saturday Club - The Maida Vale Studios, 1965 Playhouse Theatre, September 1964 15. Interview: Ray Talks About Records ' 5. Little Queenie ' Saturday Club - The Saturday Club - Maida Vale Studios, 1965 Playhouse Theatre, 1964 16. Tired Of Waiting For You - Saturday Club - 6. I'm A Lover Not A Fighter ' Top Gear - The Maida Vale Studios, 1965 Playhouse Theatre, 1964 17. Everybody's Gonna Be Happy ' Saturday 7. Interview: The Shaggy Set ' Top Gear - The Club -Maida Vale Studios, 1965 Playhouse Theatre, 1964 18. This Strange Effect ' 'You Really Got.' - 8. You Really Got Me ' Top Gear - The Aeolian Hall, 1965 Playhouse Theatre, October 1964 19. Interview: Ray Talks About "See My Friends" 9. All Day And All Of The Night ' Top Gear - The ' 'You Really Got.' Aeolian Hall, 1965 Playhouse Theatre, 1964 20. See My Friends ' 'You Really Got.' Aeolian Hall, 1965 1969 21. -

The Irony and Drug Related Themes of Photographs of the Rolling Stones ARTE 214 DECLAN RILEY

The Irony and Drug Related Themes of photographs of The Rolling Stones ARTE 214 DECLAN RILEY For our assignment we were tasked with comparing 2 photographs displayed in class. For this assignment I have chosen to compare similar photos; one of Keith Richards taken by Ethan Russel in 1972, ironically posing in front of an anti-drug poster, and the other, a portrait of Mick Jagger taken by Annie Lebovitz also taken in 1972. In this comparison, not only will I be discussing comparisons and contrasts between these two pieces but I will be highlighting the underlying theme of irony that both photos present. In 1962, the world was introduced to a band that would go on to the one of the most iconic and influential rock bands to date. Formed in London, The Rolling Stones appeared on the music scene around the same time that The Beatles were also growing in popularity. Driven by founders Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, The Rolling Stones started locally in London quickly became a worldwide phenomenon. Still a band to this day The Rolling Stone have begun to play less shows and members have begun to slow down with old age and have concentrations on their own personal music.1 The Rolling Stones are regarded as one of the most influential rock bands of all time and not only influenced the music industry but also have become a permanent fixture in ‘pop-culture’. As the photos I have chosen begin to be examined, described and compared; it is important to keep in mind the immense stardom that these musicians experienced. -

Ken Loach : Constructing Individuals

UNIVERSITE MICHEL DE MONTAIGNE – BORDEAUX III U.F.R D’ANGLAIS Ken Loach : Constructing Individuals Questions of existentialism, happiness, gender and individual / collective construction. TRAVAIL D’ETUDES ET DE RECHERCHES PRESENTE PAR ALEXANDRA BEAUFORT J UNIVERSITE MICHEL DE MONTAIGNE – BORDEAUX III U.F.R D’ANGLAIS Ken Loach : Constructing Individuals Questions of existentialism, happiness, gender and individual / collective construction. TRAVAIL D’ETUDES ET DE RECHERCHES PRESENTE PAR ALEXANDRA BEAUFORT Remerciements Je tiens à remercier: - Monsieur Joël Richard qui a accepté de diriger ce TER, pour sa confiance, son suivi et ses conseils; - Monsieur Jean François Baillon, pour son aide précieuse et sa disponibilité; - Monsieur Maurice Hugonin, pour son aide sur Aristote; - Messieurs Paul Burgess, Ken Allen, JF Buck, et les autres pour leur aide à la re- lecture; - Monsieur Fabrice Clerc, pour son soutien et son aide à la mise en page; - Tout le personnel de Parallax Pictures à Londres, pour leur gentillesse et leur compréhension; - Et enfin Ken Loach, pour son extrême gentillesse lors de l'interview, et surtout pour tous ses films, dont l'étude a toujours été passionnante et très enrichissante. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 I/ THE EXISTENTIALIST TREND IN LOACH'S FILMS. 3 1/ Against systematisation. 4 2/ The engagement of the self. 7 3/ Question of religion. 11 4/ Marxism and Existentialism: question of politics. 15 II/ THE PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS 19 1/ Learning to live 20 2/ The Aristotelian conception of citizenship. 23 3/ The organic city. 26 4/ Happiness and Socialization 29 III/ GENDER ISSUES. 33 1/ Is there a gender issue in Loach's movies? 34 2/ Out of home: from Cathy to Sarah 41 3/ Falling Standards, Fallen Males. -

The Communist Party of Great Britain Since 1920 Also by David Renton

The Communist Party of Great Britain since 1920 Also by David Renton RED SHIRTS AND BLACK: Fascism and Anti-Fascism in Oxford in the ‘Thirties FASCISM: Theory and Practice FASCISM, ANTI-FASCISM AND BRITAIN IN THE 1940s THE TWENTIETH CENTURY: A Century of Wars and Revolutions? (with Keith Flett) SOCIALISM IN LIVERPOOL: Episodes in a History of Working-Class Struggle THIS ROUGH GAME: Fascism and Anti-Fascism in European History MARX ON GLOBALISATION CLASSICAL MARXISM: Socialist Theory and the Second International The Communist Party of Great Britain since 1920 James Eaden and David Renton © James Eaden and David Renton 2002 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2002 978-0-333-94968-9 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2002 by PALGRAVE Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N. Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE is the new global academic imprint of St. -

Epilogue 231

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Noise resonance Technological sound reproduction and the logic of filtering Kromhout, M.J. Publication date 2017 Document Version Other version License Other Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kromhout, M. J. (2017). Noise resonance: Technological sound reproduction and the logic of filtering. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:30 Sep 2021 NOISE RESONANCE | EPILOGUE 231 Epilogue: Listening for the event | on the possibility of an ‘other music’ 6.1 Locating the ‘other music’ Throughout this thesis, I wrote about phonographs and gramophones, magnetic tape recording and analogue-to-digital converters, dual-ended noise reduction and dither, sine waves and Dirac impulses; in short, about chains of recording technologies that affect the sound of their output with each irrepresentable technological filtering operation. -

'Music and Remembrance: Britain and the First World War'

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Grant, P. and Hanna, E. (2014). Music and Remembrance. In: Lowe, D. and Joel, T. (Eds.), Remembering the First World War. (pp. 110-126). Routledge/Taylor and Francis. ISBN 9780415856287 This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/16364/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] ‘Music and Remembrance: Britain and the First World War’ Dr Peter Grant (City University, UK) & Dr Emma Hanna (U. of Greenwich, UK) Introduction In his research using a Mass Observation study, John Sloboda found that the most valued outcome people place on listening to music is the remembrance of past events.1 While music has been a relatively neglected area in our understanding of the cultural history and legacy of 1914-18, a number of historians are now examining the significance of the music produced both during and after the war.2 This chapter analyses the scope and variety of musical responses to the war, from the time of the war itself to the present, with reference to both ‘high’ and ‘popular’ music in Britain’s remembrance of the Great War. -

Danu Study Guide 11.12.Indd

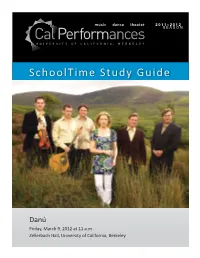

SchoolTime Study Guide Danú Friday, March 9, 2012 at 11 a.m. Zellerbach Hall, University of California, Berkeley Welcome to SchoolTime! On Friday, March 9, 2012 at 11 am, your class will a end a performance by Danú the award- winning Irish band. Hailing from historic County Waterford, Danú celebrates Irish music at its fi nest. The group’s energe c concerts feature a lively mix of both ancient music and original repertoire. For over a decade, these virtuosos on fl ute, n whistle, fi ddle, bu on accordion, bouzouki, and vocals have thrilled audiences, winning numerous interna onal awards and recording seven acclaimed albums. Using This Study Guide You can prepare your students for their Cal Performances fi eld trip with the materials in this study guide. Prior to the performance, we encourage you to: • Copy the student resource sheet on pages 2 & 3 and hand it out to your students several days before the performance. • Discuss the informa on About the Performance & Ar sts and Danú’s Instruments on pages 4-5 with your students. • Read to your students from About the Art Form on page 6-8 and About Ireland on pages 9-11. • Engage your students in two or more of the ac vi es on pages 13-14. • Refl ect with your students by asking them guiding ques ons, found on pages 2,4,6 & 9. • Immerse students further into the art form by using the glossary and resource sec ons on pages 12 &15. At the performance: Students can ac vely par cipate during the performance by: • LISTENING CAREFULLY to the melodies, harmonies and rhythms • OBSERVING how the musicians and singers work together, some mes playing in solos, duets, trios and as an ensemble • THINKING ABOUT the culture, history, ideas and emo ons expressed through the music • MARVELING at the skill of the musicians • REFLECTING on the sounds and sights experienced at the theater. -

“What Happened to the Post-War Dream?”: Nostalgia, Trauma, and Affect in British Rock of the 1960S and 1970S by Kathryn B. C

“What Happened to the Post-War Dream?”: Nostalgia, Trauma, and Affect in British Rock of the 1960s and 1970s by Kathryn B. Cox A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music Musicology: History) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Charles Hiroshi Garrett, Chair Professor James M. Borders Professor Walter T. Everett Professor Jane Fair Fulcher Associate Professor Kali A. K. Israel Kathryn B. Cox [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-6359-1835 © Kathryn B. Cox 2018 DEDICATION For Charles and Bené S. Cox, whose unwavering faith in me has always shone through, even in the hardest times. The world is a better place because you both are in it. And for Laura Ingram Ellis: as much as I wanted this dissertation to spring forth from my head fully formed, like Athena from Zeus’s forehead, it did not happen that way. It happened one sentence at a time, some more excruciatingly wrought than others, and you were there for every single sentence. So these sentences I have written especially for you, Laura, with my deepest and most profound gratitude. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Although it sometimes felt like a solitary process, I wrote this dissertation with the help and support of several different people, all of whom I deeply appreciate. First and foremost on this list is Prof. Charles Hiroshi Garrett, whom I learned so much from and whose patience and wisdom helped shape this project. I am very grateful to committee members Prof. James Borders, Prof. Walter Everett, Prof. -

Hornpipes and Disordered Dancing in the Late Lancashire Witches: a Reel Crux?

Early Theatre 16.1 (2013), 139–49 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.12745/et.16.1.8 Note Brett D. Hirsch Hornpipes and Disordered Dancing in The Late Lancashire Witches: A Reel Crux? A memorable scene in act 3 of Thomas Heywood and Richard Brome’s The Late Lancashire Witches (first performed and published 1634) plays out the bewitching of a wedding party and the comedy that ensues. As the party- goers ‘beginne to daunce’ to ‘Selengers round’, the musicians instead ‘play another tune’ and ‘then fall into many’ (F4r).1 With both diabolical interven- tion (‘the Divell ride o’ your Fiddlestickes’) and alcoholic excess (‘drunken rogues’) suspected as causes of the confusion, Doughty instructs the musi- cians to ‘begin againe soberly’ with another tune, ‘The Beginning of the World’, but the result is more chaos, with ‘Every one [playing] a seuerall tune’ at once (F4r). The music then suddenly ceases altogether, despite the fiddlers claiming that they play ‘as loud as [they] can possibly’, before smashing their instruments in frustration (F4v). With neither fiddles nor any doubt left that witchcraft is to blame, Whet- stone calls in a piper as a substitute since it is well known that ‘no Witchcraft can take hold of a Lancashire Bag-pipe, for itselfe is able to charme the Divell’ (F4v). Instructed to play ‘a lusty Horne-pipe’, the piper plays with ‘all [join- ing] into the daunce’, both ‘young and old’ (G1r). The stage directions call for the bride and bridegroom, Lawrence and Parnell, to ‘reele in the daunce’ (G1r). At the end of the dance, which concludes the scene, the piper vanishes ‘no bodie knowes how’ along with Moll Spencer, one of the dancers who, unbeknownst to the rest of the party, is the witch responsible (G1r).