Sir George Scharf As an Emerging Professional Within the Nineteenth-Century Museum World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art Union in England and the United States, 1840–60

Joy Sperling "Art, Cheap and Good:" The Art Union in England and the United States, 1840–60 Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 1, no. 1 (Spring 2002) Citation: Joy Sperling, “‘Art, Cheap and Good:’ The Art Union in England and the United States, 1840–60,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 1, no. 1 (Spring 2002), http://www. 19thc-artworldwide.org/spring02/196--qart-cheap-and-goodq-the-art-union-in-england-and- the-united-states-184060. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. ©2002 Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide Sperling: The Art Union in England and the United States, 1840–60 Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 1, no. 1 (Spring 2002) "Art, Cheap and Good:" The Art Union in England and the United States, 1840–60 by Joy Sperling "Alas, it is not for art they paint, but for the Art Union." William Thackeray, 1844[1] The "Art Union" was a nineteenth-century institution of art patronage organized on the principle of joint association by which the revenue from small individual annual membership fees was spent (after operating costs) on contemporary art, which was then redistributed among the membership by lot. The concept originated in Switzerland about 1800 and spread to some twenty locations in the German principalities by the 1830s. It was introduced to England in the late 1830s on the recommendation of a House of Commons Select Committee investigation at which Gustave Frederick Waagen, director of the Berlin Royal Academy and advocate of art unions, had testified. -

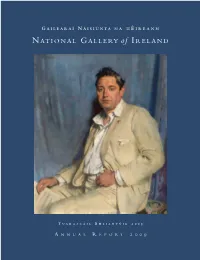

NGI Annual Report 2009 Web NGI Annual Report2001

G AILEARAÍ N ÁISIÚNTA NA HÉ IREANN N ATIONAL G ALLERY of I RELAND T UARASCÁIL B HLIANTÚIL 2009 A NNUAL R EPORT 2009 GAILEARAÍ NÁISIÚNTA NA HÉIREANN Is trí Acht Parlaiminte i 1854 a bunaíodh Gailearaí Náisiúnta na hÉireann, agus osclaíodh don phobal é i 1864. Tá breis agus 13,000 mír ann: breis agus 2,500 olaph- ictiúr, agus 10,000 píosa oibre i meáin éagsúla, lena n-áirítear uiscedhathanna, líníochtaí, priontaí agus dealbhóireacht. Is ón gceathrú céad déag go dtí an la inniu a thagann na píosaí oibre, agus tríd is tríd léirítear iontu forbairt na mórscoileanna péin- téireachta san Eoraip: Briotanach, Dúitseach, Pléimeannach, Francach, Gearmánach, Iodálach, Spáinneach agus an Ísiltír, comhlánaithe ag bailiúchán cuimsitheach d’Ealaín ó Éirinn. Ráiteas Misin Tá sé mar chuspóir ag Gailearaí Náisiúnta na hÉireann an bailúchán náisiúnta a thais- peáint, a chaomhnú, a bhainistiú, a léirmhíniú agus a fhorbairt; chun taitneamh agus tuiscint ar na hamharcealaíona a fheabhsú, agus chun saol cultúrtha, ealaíonta agus intleachtúil na nglúinte reatha agus na nglúinte sa todhchaí a fheabhsú freisin. NATIONAL GALLERY OF IRELAND The National Gallery of Ireland was founded by an Act of Parliament in 1854 and opened to the public in 1864. It houses some 13,000 items: over 2,500 oil paintings, and 10,000 works in different media including watercolours, drawings, prints and sculpture. The works range in date from the fourteenth century to the present day and broadly represent the development of the major European schools of painting: British, Dutch, Flemish, French, German, Italian, Spanish and Netherlands, complemented by a comprehensive collection of Irish art. -

Hoock Empires Bibliography

Holger Hoock, Empires of the Imagination: Politics, War, and the Arts in the British World, 1750-1850 (London: Profile Books, 2010). ISBN 978 1 86197. Bibliography For reasons of space, a bibliography could not be included in the book. This bibliography is divided into two main parts: I. Archives consulted (1) for a range of chapters, and (2) for particular chapters. [pp. 2-8] II. Printed primary and secondary materials cited in the endnotes. This section is structured according to the chapter plan of Empires of the Imagination, the better to provide guidance to further reading in specific areas. To minimise repetition, I have integrated the bibliographies of chapters within each sections (see the breakdown below, p. 9) [pp. 9-55]. Holger Hoock, Empires of the Imagination (London, 2010). Bibliography © Copyright Holger Hoock 2009. I. ARCHIVES 1. Archives Consulted for a Range of Chapters a. State Papers The National Archives, Kew [TNA]. Series that have been consulted extensively appear in ( ). ADM Admiralty (1; 7; 51; 53; 352) CO Colonial Office (5; 318-19) FO Foreign Office (24; 78; 91; 366; 371; 566/449) HO Home Office (5; 44) LC Lord Chamberlain (1; 2; 5) PC Privy Council T Treasury (1; 27; 29) WORK Office of Works (3; 4; 6; 19; 21; 24; 36; 38; 40-41; 51) PRO 30/8 Pitt Correspondence PRO 61/54, 62, 83, 110, 151, 155 Royal Proclamations b. Art Institutions Royal Academy of Arts, London Council Minutes, vols. I-VIII (1768-1838) General Assembly Minutes, vols. I – IV (1768-1841) Royal Institute of British Architects, London COC Charles Robert Cockerell, correspondence, diaries and papers, 1806-62 MyFam Robert Mylne, correspondence, diaries, and papers, 1762-1810 Victoria & Albert Museum, National Art Library, London R.C. -

A Field Awaits Its Next Audience

Victorian Paintings from London's Royal Academy: ” J* ml . ■ A Field Awaits Its Next Audience Peter Trippi Editor, Fine Art Connoisseur Figure l William Powell Frith (1819-1909), The Private View of the Royal Academy, 1881. 1883, oil on canvas, 40% x 77 inches (102.9 x 195.6 cm). Private collection -15- ALTHOUGH AMERICANS' REGARD FOR 19TH CENTURY European art has never been higher, we remain relatively unfamiliar with the artworks produced for the academies that once dominated the scene. This is due partly to the 20th century ascent of modernist artists, who naturally dis couraged study of the academic system they had rejected, and partly to American museums deciding to warehouse and sell off their academic holdings after 1930. In these more even-handed times, when seemingly everything is collectible, our understanding of the 19th century art world will never be complete if we do not look carefully at the academic works prized most highly by it. Our collective awareness is growing slowly, primarily through closer study of Paris, which, as capital of the late 19th century art world, was ruled not by Manet or Monet, but by J.-L. Gerome and A.-W. Bouguereau, among other Figure 2 Frederic Leighton (1830-1896) Study for And the Sea Gave Up the Dead Which Were in It: Male Figure. 1877-82, black and white chalk on brown paper, 12% x 8% inches (32.1 x 22 cm) Leighton House Museum, London Figure 3 Frederic Leighton (1830-1896) Elisha Raising the Son of the Shunamite Woman 1881, oil on canvas, 33 x 54 inches (83.8 x 137 cm) Leighton House Museum, London -16- J ! , /' i - / . -

VN Volume 9 (Entire Issue)

Kate Flint 1 How Do We See? Kate Flint, Provost Professor of Art History and English (University of Southern California, USA) How do we see? And how do we learn to see? These two questions, despite being highly similar, are far from identical. An increasing number of mid-Victorian commentators, who considered the act of looKing from the entwined perspectives of science and culture, investigated them. They explored and explained connections between the physiology and psychology of vision; the relationship between looking, attention, and ocular selection; and the variations in modes of seeing that come about through occupation, environment, and the spaces of sight. These, too, are the issues at the heart of the stimulating essays in this issue of Victorian Network. In 1871, the journalist Richard Hengist Horne brought out a strangely hybrid volume: The Poor Artist; or, Seven Eye-Sights and One Object. The narrative of a struggling painter, first published in 1850, was now prefaced by a ‘Preliminary Essay. On Varieties of Vision in Man.’ Horne acknowledges that the passages strung together into the essay ‘have been jotted down at various intervals, and in various parts of the globe’.1 Indeed, they constitute a collection of musings on the subject rather than a sustained argument, as though Horne’s own attention was incapable of resting steadily on a designated object. But he also recognizes that the variety of examples and exceptions he discusses precludes arriving at any firm generaliZations concerning the act of visualiZation – apart from the fact that we may extend the principle of variety in vision to the other senses. -

Unlocking Eastlake Unlocking Eastlake

ng E nlocki astlak U e CREATED BY THE YOUNG EXPLAINERS OF PLYMOUTH CITY MUSEUM AND ART GALLERY No. 1. ] SEPTEMBER 22 - DECEMBER 15, 2012. [ One Penny. A STROKE OF GENIUS. UNLOCKING EASTLAKE UNLOCKING EASTLAKE It may be because of his reserved nature that Staff at the City Museum and Art Gallery are organising a range of events connected to the Eastlake is not remembered as much as he exhibition, including lunchtime talks and family-friendly holiday workshops. INTRODUCING deserves to be. Apart from securing more Visit www.plymouth.gov.uk/museumeastlake to stay up to date with what’s on offer! than 150 paintings for the nation, Eastlake was a key figure in helping the public gain like to i uld ntro a better understanding of the history of wo d uc WALKING TRAILS e e EASTLAKE western art. Through detailed catalogues, W THE simpler ways of picture display, and the Thursday 20th September 2012: : BRITISH ART’S PUBLIC SERVANT introduction of labels enabling free access to Grand Art History Freshers Tour information, Eastlake gave the us public art. YOUNG EXPLAINERS A chance for Art History Freshers to make friends as well as see what lmost 150 years after his Article: Laura Hughes the Museum and the Young Explainers death, the name of Sir Charles Children’s Actities / Map: Joanne Lees have to offer. The tour will focus on UNLOCKING EASTLAKE’S PLYMOUTH Eastlake has failed to live up to Editor: Charlotte Slater Eastlake, Napoleon and Plymouth. the celebrity of his legacy. Designer: Sarah Stagg A Illustrator (front): Alex Hancock Saturday 3rd November 2012: Even in his hometown of Plymouth, blank faces During Eastlake’s lifetime his home city Illustrator (inside): Abi Hodgson Lorente Eastlake’s Plymouth: usually meet the question: “Who is Sir Charles of Plymouth dramatically altered as it A Family Adventure Through Time Eastlake?” Yet this cultural heavyweight was transformed itself from an ancient dockland Alice Knight Starting at the Museum with interactive acknowledged to be one of the ablest men of to a modern 19th century metropolis. -

2010-2011 Newsletter

Newsletter WILLIAMS G RADUATE PROGRAM IN THE HISTORY OF A RT OFFERED IN COLLABORATION WITH THE CLARK ACADEMIC YEAR 2010–11 Newsletter ••••• 1 1 CLASS OF 1955 MEMORIAL PROFESSOR OF ART MARC GOTLIEB Letter from the Director Greetings from Williamstown! Our New features of the program this past year include an alumni now number well over 400 internship for a Williams graduate student at the High Mu- going back nearly 40 years, and we seum of Art. Many thanks to Michael Shapiro, Philip Verre, hope this newsletter both brings and all the High staff for partnering with us in what promises back memories and informs you to serve as a key plank in our effort to expand opportuni- of our recent efforts to keep the ties for our graduate students in the years to come. We had a thrilling study-trip to Greece last January with the kind program academically healthy and participation of Elizabeth McGowan; coming up we will be indeed second to none. To our substantial community of alumni heading to Paris, Rome, and Naples. An ambitious trajectory we must add the astonishingly rich constellation of art histori- to be sure, and in Rome and Naples in particular we will be ans, conservators, and professionals in related fields that, for a exploring 16th- and 17th-century art—and perhaps some brief period, a summer, or on a permanent basis, make William- sense of Rome from a 19th-century point of view, if I am al- stown and its vicinity their home. The atmosphere we cultivate is lowed to have my way. -

Eastlake's Scholarly and Artistic Achievements Wednesday 10

Eastlake's Scholarly and Artistic Achievements Wednesday 10 October 2012 Lizzie Hill & Laura Hughes Overview I will begin this Art Bite with a quotation from A Century of British Painters by Samuel and Richard Redgrave, who refer to Eastlake as one of "a few exceptional painters who have served the art they love better by their lives than their brush" . This observation is in keeping with the norm of contemporary views in which Eastlake is first and foremost seen as an art historian and collector. However, as a man who began his career as a painter, it seems it would be interesting to explore both of these aspects of his life. Therefore, this Art Bite will be examining the validity of this critique by evaluating Eastlake's artistic outputs and scholarly achievements, and putting these two aspects of his life in direct relation to each other. By doing this, the aim behind this Art Bite is to uncover the fundamental reason behind Eastlake's contemporary and historical reputation, and ultimately to answer; - What proved to be Eastlake's best weapon in entering the Art Historical canon: his brain or his brush? Introduction So, who was Sir Charles Lock Eastlake? To properly be able to compare his reputation as an art historian versus being a painter himself, we need to know the basic facts about the man. A very brief overview is that Eastlake was born in Plymouth in 1793 and from an early age was determined to be a painter. He was the first student of the notable artist Benjamin Haydon in January 1809 and received tuition from the Royal Academy schools from late 1809. -

Statutes and Rules for the British Museum

(ft .-3, (*y Of A 8RI A- \ Natural History Museum Library STATUTES AND RULES BRITISH MUSEUM STATUTES AND RULES FOR THE BRITISH MUSEUM MADE BY THE TRUSTEES In Pursuance of the Act of Incorporation 26 George II., Cap. 22, § xv. r 10th Decembei , 1898. PRINTED BY ORDER OE THE TRUSTEES LONDON : MDCCCXCYIII. PRINTED BY WOODFALL AND KINDER, LONG ACRE LONDON TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I. PAGE Meetings, Functions, and Privileges of the Trustees . 7 CHAPTER II. The Director and Principal Librarian . .10 Duties as Secretary and Accountant . .12 The Director of the Natural History Departments . 14 CHAPTER III. Subordinate Officers : Keepers and Assistant Keepers 15 Superintendent of the Reading Room . .17 Assistants . 17 Chief Messengers . .18 Attendance of Officers at Meetings, etc. -19 CHAPTER IV. Admission to the British Museum : Reading Room 20 Use of the Collections 21 6 CHAPTER V, Security of the Museum : Precautions against Fire, etc. APPENDIX. Succession of Trustees and Officers . Succession of Officers in Departments 7 STATUTES AND RULES. CHAPTER I. Of the Meetings, Functions, and Privileges of the Trustees. 1. General Meetings of the Trustees shall chap. r. be held four times in the year ; on the second Meetings. Saturday in May and December at the Museum (Bloomsbury) and on the fourth Saturday in February and July at the Museum (Natural History). 2. Special General Meetings shall be sum- moned by the Director and Principal Librarian (hereinafter called the Director), upon receiving notice in writing to that effect signed by two Trustees. 3. There shall be a Standing Committee, standing . • Committee. r 1 1 t-» • 1 t> 1 consisting 01 the three Principal 1 rustees, the Trustee appointed by the Crown, and sixteen other Trustees to be annually appointed at the General Meeting held on the second Saturday in May. -

Kensington and Chelsea

Kensington Open House London and Chelsea Self-Guided Itinerary Nearest station: Highstreet Kensington Leighton House Museum, 12 Holland Park Rd, Kensington, London W14 8LZ Originally the studio home of Lord Leighton, President of the Royal Academy, the house is one of the most remarkable buildings of 19C. The museum houses an outstanding collection of high Victorian art, including works by Leighton him- self. Directions: Walk south-west on Kensington High St/A315 towards Wrights Ln > Turn right onto Melbury Rd > Turn left onto Holland Park Rd 10 min (0.5 mi) 18 Stafford Terrace, Kensington, London W8 7BH From 1875, the home of the Punch cartoonist Edward Linley Sambourne, his wife Marion, their two children and their live-in servants. The house is recognised as the best surviving example of a late Victorian middle-class home in the UK. Directions: Walk north-east on Holland Park Rd towards St Mary Abbots Terrace > Turn right onto Melbury Rd > Turn left onto Kensington High St/A315 > Turn left onto Phillimore Gardens > Turn right onto Stafford Terrace 8 min (0.4 mi) Kensington Palace Gardens, London This wide open street runs alongside Kensington Gardens and features stereotypical architecture of the area. Large family homes line the street, most are now occupied by Embassies or other cultural companies. Page 1 Open House London Directions: Walk north-east on Stafford Terrace towards Argyll Rd > Turn right onto Argyll Rd > Turn left onto Kensington High St/A315 > Turn left onto Kensington Palace Gardens 14 min (0.7 mi) Embassy of Slovakia, Kensington, London W8 4QY Modern Brutalist-style building awarded by RIBA in 1971. -

'This Will Be a Popular Picture': Giovanni Battista Moroni's Tailor and the Female Gaze

‘This will be a popular picture’: Giovanni Battista Moroni’s Tailor and the Female Gaze Lene Østermark-Johansen In October 1862, when Charles Eastlake had secured the purchase of Giovanni Battista Moroni’s The Tailor (c. 1570) for the National Gallery (Fig. 1), he noted with satisfaction: Portrait of a tailor in a white doublet with minute slashes — dark reddish nether dress — a leather belt [strap & buckle] round the end of the white dress. He stands before a table with scissors in his rt hand, & a piece of [black] cloth in the left. Fig. 1: Giovanni Battista Moroni, The Tailor, c. 1570, oil on canvas, 99.5 × 77 cm, National Gallery, London. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. 2 The hands excellent — the head low in tone but good (one or two spotty lights only too much cleaned) the ear carefully & well painted — All in good state — The lowness of the tone in the face the only objection — Background varied in darkness — light enough to relieve dark side of face & d. air — darker in left side & below — quite el.1 Eastlake’s description, focusing on the effects of colour, light, and the state of preservation, does not give away much about the charismatic qualities of the painting. With his final remark, ‘quite eligible’, he recognizes one of the most engaging of the old master portraits as suitable for purchase by the National Gallery. Eastlake’s wife Elizabeth immediately perceived the powerful presence of the tailor and made the following entry in her journal: ‘It is a celebrated picture, called the “Taglia Panni.”2 The tailor, a bright-looking man with a ruff, has his shears in his beautifully painted hands, and is looking at the spectator. -

Joan Plantagenet: the Fair Maid of Kent by Susan W

RICE UNIVERSITY JOAN PLANTAGANET THE FAIR MAID OF KENT by Susan W. Powell A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts Thesis Director's Signature: Houston, Texas April, 1973 ABSTRACT Joan Plantagenet: The Fair Maid of Kent by Susan W. Powell Joan plantagenet, Known as the Fair Maid of Kent, was born in 1328. She grew to be one of the most beautiful and influential women of her age, Princess of Wales by her third marriage and mother of King Richard II. The study of her life sheds new light on the role of an intelligent woman in late fourteenth century England and may reveal some new insights into the early regnal years of her son. There are several aspects of Joan of Kent's life which are of interest. The first chapter will consist of a biographical sketch to document the known facts of a life which spanned fifty-seven years of one of the most vivid periods in English history. Joan of Kent's marital history has been the subject of historical confusion and debate. The sources of that confusion will be discussed, the facts clarified, and a hypothesis suggested as to the motivations behind the apparent actions of the personages involved. There has been speculation that it was Joan of Kent's garter for which the Order of the Garter was named. This theory was first advanced by Selden and has persisted in this century in the articles of Margaret Galway. It has been accepted by May McKisack and other modern historians.