VN Volume 9 (Entire Issue)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NGI Annual Report 2009 Web NGI Annual Report2001

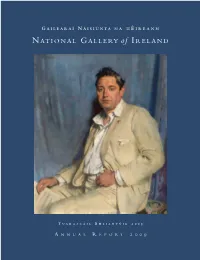

G AILEARAÍ N ÁISIÚNTA NA HÉ IREANN N ATIONAL G ALLERY of I RELAND T UARASCÁIL B HLIANTÚIL 2009 A NNUAL R EPORT 2009 GAILEARAÍ NÁISIÚNTA NA HÉIREANN Is trí Acht Parlaiminte i 1854 a bunaíodh Gailearaí Náisiúnta na hÉireann, agus osclaíodh don phobal é i 1864. Tá breis agus 13,000 mír ann: breis agus 2,500 olaph- ictiúr, agus 10,000 píosa oibre i meáin éagsúla, lena n-áirítear uiscedhathanna, líníochtaí, priontaí agus dealbhóireacht. Is ón gceathrú céad déag go dtí an la inniu a thagann na píosaí oibre, agus tríd is tríd léirítear iontu forbairt na mórscoileanna péin- téireachta san Eoraip: Briotanach, Dúitseach, Pléimeannach, Francach, Gearmánach, Iodálach, Spáinneach agus an Ísiltír, comhlánaithe ag bailiúchán cuimsitheach d’Ealaín ó Éirinn. Ráiteas Misin Tá sé mar chuspóir ag Gailearaí Náisiúnta na hÉireann an bailúchán náisiúnta a thais- peáint, a chaomhnú, a bhainistiú, a léirmhíniú agus a fhorbairt; chun taitneamh agus tuiscint ar na hamharcealaíona a fheabhsú, agus chun saol cultúrtha, ealaíonta agus intleachtúil na nglúinte reatha agus na nglúinte sa todhchaí a fheabhsú freisin. NATIONAL GALLERY OF IRELAND The National Gallery of Ireland was founded by an Act of Parliament in 1854 and opened to the public in 1864. It houses some 13,000 items: over 2,500 oil paintings, and 10,000 works in different media including watercolours, drawings, prints and sculpture. The works range in date from the fourteenth century to the present day and broadly represent the development of the major European schools of painting: British, Dutch, Flemish, French, German, Italian, Spanish and Netherlands, complemented by a comprehensive collection of Irish art. -

The Challenges of French Impressionism in Great Britain

Crossing the Channel: The Challenges of French Impressionism in Great Britain By Catherine Cheney Senior Honors Thesis Department of Art History University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill April 8, 2016 Approved: 1 Introduction: French Impressionism in England As Impressionism spread throughout Europe in the late nineteenth century, the movement took hold in the British art community and helped to change the fundamental ways in which people viewed and collected art. Impressionism made its debut in London in 1870 when Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Paul Durand-Ruel sought safe haven in London during the Franco- Prussian war. The two artists created works of London landscapes done in the new Impressionist style. Paul Durand-Ruel, a commercial dealer, marketed the Impressionist works of these two artists and of the other Impressionist artists that he brought over from Paris. The movement was officially organized for the First Impressionist Exhibition in 1874 in Paris, but the initial introduction in London laid the groundwork for promoting this new style throughout the international art world. This thesis will explore, first, the cultural transformations of London that allowed for the introduction of Impressionism as a new style in England; second, the now- famous Thames series that Monet created in the 1890s and notable exhibitions held in London during the time; and finally, the impact Impressionism had on private collectors and adding Impressionist works to the national collections. With the exception of Edouard Manet, who met with success at the Salon in Paris over the years and did not exhibit with the Impressionists, the modern artists were not received well. -

Japonisme in Britain - a Source of Inspiration: J

Japonisme in Britain - A Source of Inspiration: J. McN. Whistler, Mortimer Menpes, George Henry, E.A. Hornel and nineteenth century Japan. Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of Art, University of Glasgow. By Ayako Ono vol. 1. © Ayako Ono 2001 ProQuest Number: 13818783 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818783 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 122%'Cop7 I Abstract Japan held a profound fascination for Western artists in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The influence of Japanese art is a phenomenon that is now called Japonisme , and it spread widely throughout Western art. It is quite hard to make a clear definition of Japonisme because of the breadth of the phenomenon, but it could be generally agreed that it is an attempt to understand and adapt the essential qualities of Japanese art. This thesis explores Japanese influences on British Art and will focus on four artists working in Britain: the American James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), the Australian Mortimer Menpes (1855-1938), and two artists from the group known as the Glasgow Boys, George Henry (1858-1934) and Edward Atkinson Hornel (1864-1933). -

2017 Annual Report 2017 NATIONAL GALLERY of IRELAND

National Gallery of Ireland Gallery of National Annual Report 2017 Annual Report 2017 Annual Report nationalgallery.ie Annual Report 2017 Annual Report 2017 NATIONAL GALLERY OF IRELAND 02 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Our mission is to care for, interpret, develop and showcase art in a way that makes the National Gallery of Ireland an exciting place to encounter art. We aim to provide an outstanding experience that inspires an interest in and an appreciation of art for all. We are dedicated to bringing people and their art together. 03 NATIONAL GALLERY OF IRELAND 04 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Contents Introducion 06 Chair’s Foreword 06 Director’s Review 10 Year at a Glance 2017 14 Development & Fundraising 20 Friends of the National Gallery of Ireland 26 The Reopening 15 June 2017 34 Collections & Research 51 Acquisition Highlights 52 Exhibitions & Publications 66 Conservation & Photography 84 Library & Archives 90 Public Engagement 97 Education 100 Visitor Experience 108 Digital Engagement 112 Press & Communications 118 Corporate Services 123 IT Department 126 HR Department 128 Retail 130 Events 132 Images & Licensing Department 134 Operations Department 138 Board of Governors & Guardians 140 Financial Statements 143 Appendices 185 Appendix 01 \ Acquisitions 2017 186 Appendix 02 \ Loans 2017 196 Appendix 03 \ Conservation 2017 199 05 NATIONAL GALLERY OF IRELAND Chair’s Foreword The Gallery took a major step forward with the reopening, on 15 June 2017, of the refurbished historic wings. The permanent collection was presented in a new chronological display, following extensive conservation work and logistical efforts to prepare all aspects of the Gallery and its collections for the reopening. -

Národní Galerie V Čr a Uk

Masarykova univerzita Ekonomicko-správní fakulta Studijní obor: Veřejná ekonomika INSTITUCIONÁLNÍ KOMPARACE KONTINENTÁLNÍHO A ANGLOAMERICKÉHO MODELU: NÁRODNÍ GALERIE V ČR A UK Institutional comparison of a continental and an Anglo- american models: National Gallery in UK and CZ Diplomová práce Vedoucí diplomové práce: Autor: Ing. František Svoboda, Ph.D. Bc. Veronika Králíková Kyjov, 2009 Jméno a příjmení autora: Veronika Králíková Název diplomové práce: Institucionální komparace kontinentálního a angloamerického modelu: Národní Galerie ČR a UK Název v angličtině: Institutional comparison of a continental and an Anglo- american models: National Gallery in UK and CZ Katedra: Veřejná ekonomika Vedoucí diplomové práce: Ing. František Svoboda, Ph.D. Rok obhajoby: 2009 Anotace Předmětem diplomové práce „Institucionální komparace kontinentálního a angloamerického modelu: Národní Galerie ČR a UK“ je analýza historického vývoje těchto institucí a jejich vzájemná komparace. První část popisuje historický vývoj a tedy i východiska, na kterých byly obě galerie vybudovány. Druhá část je věnována dnešní podobě galerií. Závěrečná kapitola je zaměřena na jejich vzájemnou komparaci. Annotation The objective of the thesis „Institutional comparison of a continental and an Anglo-american models: National Gallery in UK and CZ“ is historical development analysis and their mutual comparison. The first part describes the historical making and thus also origins of the establishment of both galleries. The second part presents their contemporary form. The closing -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Summerfield, Angela (2007). Interventions : Twentieth-century art collection schemes and their impact on local authority art gallery and museum collections of twentieth- century British art in Britain. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University, London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17420/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] 'INTERVENTIONS: TWENTIETII-CENTURY ART COLLECTION SCIIEMES AND THEIR IMPACT ON LOCAL AUTIIORITY ART GALLERY AND MUSEUM COLLECTIONS OF TWENTIETII-CENTURY BRITISII ART IN BRITAIN VOLUME III Angela Summerfield Ph.D. Thesis in Museum and Gallery Management Department of Cultural Policy and Management, City University, London, August 2007 Copyright: Angela Summerfield, 2007 CONTENTS VOLUME I ABSTRA eT...........................•.•........•........................................... ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................... xi CHAPTER l:INTRODUCTION................................................. 1 SECTION J THE NATURE AND PURPOSE OF PUBLIC ART GALLERIES, MUSEUMS AND THEIR ART COLLECTIONS.......................................................................... -

Alfred De Rothschild As Collector and Connoisseur

Butlers and boardrooms: Alfred de Rothschild as collector and connoisseur Alfred de Rothschild (1842–1918) was a flamboyant dandy whose sumptuous taste impressed and amused Edwardian society. As a connoisseur, however, he had a considerable and lasting impact on the way we perceive our national collections. Jonathan Conlin reveals another side to the foppish caricature. In the family tree of the English branch of the Rothschilds, Alfred de Rothschild is easily overlooked. A second son, a reluctant banker who left no legitimate offspring, Alfred was an active collector with a style of his own. In the years after his death, however, the paintings and other furnishings from his two residences at Seamore Place in London and Halton in Buckinghamshire were dispersed. The former was demolished in 1938, the latter sold to the War Office in 1918 after war-time use by the Royal Flying Corps as an officers’ mess. Although the massive conservatory and lavish gardens have gone, the central block of Halton has been care- fully preserved by the RAF. Its popularity as a film location notwithstanding, security concerns have inevitably left this monument to Rothschild taste largely off-limits to the public. Alfred himself would probably be entirely forgotten today, had the contrast between his diminutive physical presence and flamboyant lifestyle not caught the eye of Max Beerbohm. Satires such as Roughing it at Halton have immortalised Alfred as an exquisite Edwardian hypochondriac, a Fabergé Humpty-Dumpty terrified that he might get broken after all, despite having all the King’s doctors and all his footmen on hold to put him back together again. -

The Role of the Royal Academy in English Art 1918-1930. COWDELL, Theophilus P

The role of the Royal Academy in English art 1918-1930. COWDELL, Theophilus P. Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20673/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version COWDELL, Theophilus P. (1980). The role of the Royal Academy in English art 1918-1930. Doctoral, Sheffield Hallam University (United Kingdom).. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk onemeia u-ny roiyiecnmc 100185400 4 Mill CC rJ o x n n Author Class Title Sheffield Hallam University Learning and IT Services Adsetts Centre City Campus Sheffield S1 1WB NOT FOR LOAN Return to Learning Centre of issue Fines are charged at 50p per hour Sheffield Haller* University Learning snd »T Services Adsetts Centre City Csmous Sheffield SI 1WB ^ AUG 2008 S I2 J T 1 REFERENCE ProQuest Number: 10702010 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10702010 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

Formování Veřejného Zájmu: Studie Vzniku a Rozvoje Londýnské National Gallery

Masarykova univerzita Ekonomicko-správní fakulta Studijní obor: Evropská hospodářská, správní a kulturní studia FORMOVÁNÍ VEŘEJNÉHO ZÁJMU: STUDIE VZNIKU A ROZVOJE LONDÝNSKÉ NATIONAL GALLERY Formulating of public interest: essay about the founding and evolving of the National Gallery Bakalářská práce Vedoucí bakalářské práce: Autor: Ing. František SVOBODA, Ph.D. Aleš HORÁČEK Brno, květen 2010 Jméno a příjmení autora: Aleš Horáček Název bakalářské práce: Formování veřejného zájmu: studie vzniku a rozvoje londýnské National Gallery Název v angličtině: Formulating of public interest: essay about the founding and evolving of the National Gallery Katedra : Veřejná ekonomie Vedoucí bakalářské práce: Ing. František Svoboda, Ph.D. Rok obhajoby: 2010 Anotace v češtině: Předmětem bakalářské práce na téma „Formování veřejného zájmu: studie vzniku a rozvoje londýnské National Gallery" je analýza prvků veřejného zájmu v péči o kulturní dědictví společnosti, tedy takových faktorů , které stály i u zrodu jedné z největších světových galerií světa - londýnské National Gallery. Této problematice je věnována první část. Díky těmto a dalším vlivům se galerie v čase postupně vyvíjela a rostla, aţ dospěla do současného stavu. Tento proces a jeho výsledky jsou pak náplní druhé části mé práce. Anotace v angličtině: The objective of my bachelor work " Formulating of public interest: essay about the founding and evolving of the National Gallery", is the analysis of the components of public interest in the cultural heritage of our society, i.e. such factors, that led to the creation of one of the greatest galleries in the world - the National Gallery. The first part is dedicated to this topic. Due the influence of this factors, the gallery has been evolving ang getting bigger and ultimately reached the present state. -

Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University In

379 1481 n o, 565 ROGER FRY: CRITIC TO AN AGE THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By B. Jane England, B.A. Denton, Texas December, 1979 England, B. Jane. , Roger Fry : Critic To An Age. , Master of Arts (History) , December, 1979, 155 pp., bibliography, 73 titles. This study seeks to determine Roger Fry's position in the cultural and aesthetic dynamics of his era by examining Fry's critical writings and those of his predecessors, contemporaries, and successors. Based on Fry's published works, this thesis begins with a biographical survey, followed by a chronological examination of the evolution of Fry's aesthetics. Equally important are his stance as a champion of modern French art, his role as an art historian, and his opinions regarding British art. The fifth chapter analyzes the relationship between Fry's Puritan background and his basic attitudes. Emphasis is given to his aesthetic, social, and cultural commentaries which indicate that Fry reflected and participated in the artistic, philosophical, and social ferment of his age and thereby contributed to the alteration of British taste. Q 1980 BARBARA JANE ENGLAND ALL RIGHTS RESERVED TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chapter ......1 I. INTRODUCTION . II. ROGER FRY'S AESTHETICS .. 17 III. THE CHAMPION OF MODERN ART . 56 IV. ART HISTORY AND BRITISH ART . ." . w w. a. ". 83 V. THE AESTHETIC PURITAN . .s . 112 VI. CONCLUSION . ! . 142 BIBLIOGRAPHY.. ....... 150 iii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION The materialistic, technological, scientific orientation of twentieth century life has often produced an attitude which questions the value and negates the role of art in modern society. -

Crossing the Channel: the Challenges of French Impressionism in Great Britain

Crossing the Channel: The Challenges of French Impressionism in Great Britain By Catherine Cheney Senior Honors Thesis Department of Art History University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill April 8, 2016 Approved: __________________________________ Dr. Daniel Sherman, Thesis Advisor Dr. Eliza Richards, Reader Dr. Tatiana String, Reader 1 Introduction: French Impressionism in England As Impressionism spread throughout Europe in the late nineteenth century, the movement took hold in the British art community and helped to change the fundamental ways in which people viewed and collected art. Impressionism made its debut in London in 1870 when Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Paul Durand-Ruel sought safe haven in London during the Franco- Prussian war. The two artists created works of London landscapes done in the new Impressionist style. Paul Durand-Ruel, a commercial dealer, marketed the Impressionist works of these two artists and of the other Impressionist artists that he brought over from Paris. The movement was officially organized for the First Impressionist Exhibition in 1874 in Paris, but the initial introduction in London laid the groundwork for promoting this new style throughout the international art world. This thesis will explore, first, the cultural transformations of London that allowed for the introduction of Impressionism as a new style in England; second, the now- famous Thames series that Monet created in the 1890s and notable exhibitions held in London during the time; and finally, the impact Impressionism had on private collectors and adding Impressionist works to the national collections. With the exception of Edouard Manet, who met with success at the Salon in Paris over the years and did not exhibit with the Impressionists, the modern artists were not received well. -

Sir George Scharf As an Emerging Professional Within the Nineteenth-Century Museum World

A man of ‘unflagging zeal and industry’: Sir George Scharf as an emerging professional within the nineteenth-century museum world Elizabeth Heath Figure 1: Sir George Scharf, by Walter William Ouless, oil on canvas, 1885, NPG 985. © National Portrait Gallery, London Sir George Scharf was appointed first secretary of the newly established National Portrait Gallery early in 1857, becoming director in 1882 and retiring shortly before his death, in 1895 (fig. 1). Applied by the Gallery’s Board of Trustees when formally recording this event in their annual report, the phrase quoted in the title indicates the strength of Scharf’s commitment to his duties over the course of a career that spanned five decades.1 As custodian of the national portraits, Scharf’s remit encompassed every aspect of Gallery activity. Whilst he held responsibility for the display, interpretation and conservation of the collection in its earliest days, he also 1 Lionel Cust, 12 Sep. 1895, NPG Report of the Trustees 1895, 4, Heinz Archive and Library, NPG. Journal of Art Historiography Number 18 June 2018 Elizabeth Heath Sir George Scharf as an emerging professional within the nineteenth-century museum world devoted a significant amount of time to research into the portraits.2 To this end, Scharf oversaw the establishment of an on-site research library of engraved portraits, periodicals, books and documents. Coupled with his meticulous investigations into works in private and public collections across Britain, this served as a vital resource for authenticating potential portrait acquisitions. In recording what he saw by means of densely annotated sketches and tracings, Scharf developed a procedure for the documentation, identification and authentication of portraiture, which continues to inform the research practice of the Institution.