2 Vision, Spatiality and Connoisseurship Alison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

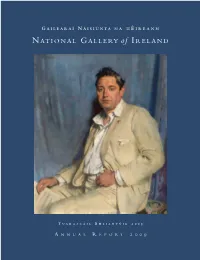

NGI Annual Report 2009 Web NGI Annual Report2001

G AILEARAÍ N ÁISIÚNTA NA HÉ IREANN N ATIONAL G ALLERY of I RELAND T UARASCÁIL B HLIANTÚIL 2009 A NNUAL R EPORT 2009 GAILEARAÍ NÁISIÚNTA NA HÉIREANN Is trí Acht Parlaiminte i 1854 a bunaíodh Gailearaí Náisiúnta na hÉireann, agus osclaíodh don phobal é i 1864. Tá breis agus 13,000 mír ann: breis agus 2,500 olaph- ictiúr, agus 10,000 píosa oibre i meáin éagsúla, lena n-áirítear uiscedhathanna, líníochtaí, priontaí agus dealbhóireacht. Is ón gceathrú céad déag go dtí an la inniu a thagann na píosaí oibre, agus tríd is tríd léirítear iontu forbairt na mórscoileanna péin- téireachta san Eoraip: Briotanach, Dúitseach, Pléimeannach, Francach, Gearmánach, Iodálach, Spáinneach agus an Ísiltír, comhlánaithe ag bailiúchán cuimsitheach d’Ealaín ó Éirinn. Ráiteas Misin Tá sé mar chuspóir ag Gailearaí Náisiúnta na hÉireann an bailúchán náisiúnta a thais- peáint, a chaomhnú, a bhainistiú, a léirmhíniú agus a fhorbairt; chun taitneamh agus tuiscint ar na hamharcealaíona a fheabhsú, agus chun saol cultúrtha, ealaíonta agus intleachtúil na nglúinte reatha agus na nglúinte sa todhchaí a fheabhsú freisin. NATIONAL GALLERY OF IRELAND The National Gallery of Ireland was founded by an Act of Parliament in 1854 and opened to the public in 1864. It houses some 13,000 items: over 2,500 oil paintings, and 10,000 works in different media including watercolours, drawings, prints and sculpture. The works range in date from the fourteenth century to the present day and broadly represent the development of the major European schools of painting: British, Dutch, Flemish, French, German, Italian, Spanish and Netherlands, complemented by a comprehensive collection of Irish art. -

VN Volume 9 (Entire Issue)

Kate Flint 1 How Do We See? Kate Flint, Provost Professor of Art History and English (University of Southern California, USA) How do we see? And how do we learn to see? These two questions, despite being highly similar, are far from identical. An increasing number of mid-Victorian commentators, who considered the act of looKing from the entwined perspectives of science and culture, investigated them. They explored and explained connections between the physiology and psychology of vision; the relationship between looking, attention, and ocular selection; and the variations in modes of seeing that come about through occupation, environment, and the spaces of sight. These, too, are the issues at the heart of the stimulating essays in this issue of Victorian Network. In 1871, the journalist Richard Hengist Horne brought out a strangely hybrid volume: The Poor Artist; or, Seven Eye-Sights and One Object. The narrative of a struggling painter, first published in 1850, was now prefaced by a ‘Preliminary Essay. On Varieties of Vision in Man.’ Horne acknowledges that the passages strung together into the essay ‘have been jotted down at various intervals, and in various parts of the globe’.1 Indeed, they constitute a collection of musings on the subject rather than a sustained argument, as though Horne’s own attention was incapable of resting steadily on a designated object. But he also recognizes that the variety of examples and exceptions he discusses precludes arriving at any firm generaliZations concerning the act of visualiZation – apart from the fact that we may extend the principle of variety in vision to the other senses. -

Unlocking Eastlake Unlocking Eastlake

ng E nlocki astlak U e CREATED BY THE YOUNG EXPLAINERS OF PLYMOUTH CITY MUSEUM AND ART GALLERY No. 1. ] SEPTEMBER 22 - DECEMBER 15, 2012. [ One Penny. A STROKE OF GENIUS. UNLOCKING EASTLAKE UNLOCKING EASTLAKE It may be because of his reserved nature that Staff at the City Museum and Art Gallery are organising a range of events connected to the Eastlake is not remembered as much as he exhibition, including lunchtime talks and family-friendly holiday workshops. INTRODUCING deserves to be. Apart from securing more Visit www.plymouth.gov.uk/museumeastlake to stay up to date with what’s on offer! than 150 paintings for the nation, Eastlake was a key figure in helping the public gain like to i uld ntro a better understanding of the history of wo d uc WALKING TRAILS e e EASTLAKE western art. Through detailed catalogues, W THE simpler ways of picture display, and the Thursday 20th September 2012: : BRITISH ART’S PUBLIC SERVANT introduction of labels enabling free access to Grand Art History Freshers Tour information, Eastlake gave the us public art. YOUNG EXPLAINERS A chance for Art History Freshers to make friends as well as see what lmost 150 years after his Article: Laura Hughes the Museum and the Young Explainers death, the name of Sir Charles Children’s Actities / Map: Joanne Lees have to offer. The tour will focus on UNLOCKING EASTLAKE’S PLYMOUTH Eastlake has failed to live up to Editor: Charlotte Slater Eastlake, Napoleon and Plymouth. the celebrity of his legacy. Designer: Sarah Stagg A Illustrator (front): Alex Hancock Saturday 3rd November 2012: Even in his hometown of Plymouth, blank faces During Eastlake’s lifetime his home city Illustrator (inside): Abi Hodgson Lorente Eastlake’s Plymouth: usually meet the question: “Who is Sir Charles of Plymouth dramatically altered as it A Family Adventure Through Time Eastlake?” Yet this cultural heavyweight was transformed itself from an ancient dockland Alice Knight Starting at the Museum with interactive acknowledged to be one of the ablest men of to a modern 19th century metropolis. -

Eastlake's Scholarly and Artistic Achievements Wednesday 10

Eastlake's Scholarly and Artistic Achievements Wednesday 10 October 2012 Lizzie Hill & Laura Hughes Overview I will begin this Art Bite with a quotation from A Century of British Painters by Samuel and Richard Redgrave, who refer to Eastlake as one of "a few exceptional painters who have served the art they love better by their lives than their brush" . This observation is in keeping with the norm of contemporary views in which Eastlake is first and foremost seen as an art historian and collector. However, as a man who began his career as a painter, it seems it would be interesting to explore both of these aspects of his life. Therefore, this Art Bite will be examining the validity of this critique by evaluating Eastlake's artistic outputs and scholarly achievements, and putting these two aspects of his life in direct relation to each other. By doing this, the aim behind this Art Bite is to uncover the fundamental reason behind Eastlake's contemporary and historical reputation, and ultimately to answer; - What proved to be Eastlake's best weapon in entering the Art Historical canon: his brain or his brush? Introduction So, who was Sir Charles Lock Eastlake? To properly be able to compare his reputation as an art historian versus being a painter himself, we need to know the basic facts about the man. A very brief overview is that Eastlake was born in Plymouth in 1793 and from an early age was determined to be a painter. He was the first student of the notable artist Benjamin Haydon in January 1809 and received tuition from the Royal Academy schools from late 1809. -

The Challenges of French Impressionism in Great Britain

Crossing the Channel: The Challenges of French Impressionism in Great Britain By Catherine Cheney Senior Honors Thesis Department of Art History University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill April 8, 2016 Approved: 1 Introduction: French Impressionism in England As Impressionism spread throughout Europe in the late nineteenth century, the movement took hold in the British art community and helped to change the fundamental ways in which people viewed and collected art. Impressionism made its debut in London in 1870 when Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Paul Durand-Ruel sought safe haven in London during the Franco- Prussian war. The two artists created works of London landscapes done in the new Impressionist style. Paul Durand-Ruel, a commercial dealer, marketed the Impressionist works of these two artists and of the other Impressionist artists that he brought over from Paris. The movement was officially organized for the First Impressionist Exhibition in 1874 in Paris, but the initial introduction in London laid the groundwork for promoting this new style throughout the international art world. This thesis will explore, first, the cultural transformations of London that allowed for the introduction of Impressionism as a new style in England; second, the now- famous Thames series that Monet created in the 1890s and notable exhibitions held in London during the time; and finally, the impact Impressionism had on private collectors and adding Impressionist works to the national collections. With the exception of Edouard Manet, who met with success at the Salon in Paris over the years and did not exhibit with the Impressionists, the modern artists were not received well. -

Japonisme in Britain - a Source of Inspiration: J

Japonisme in Britain - A Source of Inspiration: J. McN. Whistler, Mortimer Menpes, George Henry, E.A. Hornel and nineteenth century Japan. Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of Art, University of Glasgow. By Ayako Ono vol. 1. © Ayako Ono 2001 ProQuest Number: 13818783 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818783 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 122%'Cop7 I Abstract Japan held a profound fascination for Western artists in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The influence of Japanese art is a phenomenon that is now called Japonisme , and it spread widely throughout Western art. It is quite hard to make a clear definition of Japonisme because of the breadth of the phenomenon, but it could be generally agreed that it is an attempt to understand and adapt the essential qualities of Japanese art. This thesis explores Japanese influences on British Art and will focus on four artists working in Britain: the American James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), the Australian Mortimer Menpes (1855-1938), and two artists from the group known as the Glasgow Boys, George Henry (1858-1934) and Edward Atkinson Hornel (1864-1933). -

Cheltlf12 Brochure

SponSorS & SupporterS Title sponsor In association with Broadcast Partner Principal supporters Global Banking Partner Major supporters Radio Partner Festival Partners Official Wine Working in partnership Official Cider 2 The Times Cheltenham Literature Festival dIREctor Festival Assistant Jane Furze Hannah Evans Artistic dIREctor Festival INTERNS Sarah Smyth Lizzie Atkinson, Jen Liggins BOOK IT! dIREctor development dIREctor Jane Churchill Suzy Hillier Festival Managers development OFFIcER Charles Haynes, Nicola Tuxworth Claire Coleman Festival Co-ORdinator development OFFIcER Rose Stuart Alison West Welcome what words will you use to describe your festival experience? Whether it’s Jazz, Science, Music or Literature, a Cheltenham Festival experience can be intellectually challenging, educational, fun, surprising, frustrating, shocking, transformational, inspiring, comical, beautiful, odd, even life-changing. And this year’s The Times Cheltenham Literature Festival is no different. As you will see when you browse this brochure, the Festival promises Contents 10 days of discussion, debate and interview, plus lots of new ways to experience and engage with words and ideas. It’s a true celebration of 2012 NEWS 3 - 9 the power of the word - with old friends, new writers, commentators, What’s happening at this year’s Festival celebrities, sports people and scientists, and from children’s authors, illustrators, comedians and politicians to leading opinion-formers. FESTIVAL PROGRAMME 10 - 89 Your day by day guide to events I can’t praise the team enough for their exceptional dedication and flair in BOOK IT! 91 - 101 curating this year’s inspiring programme. However, there would be no Festival Our Festival for families and without the wonderful enthusiasm of our partners and loyal audiences and we young readers are extremely grateful for all the support we receive. -

2017 Annual Report 2017 NATIONAL GALLERY of IRELAND

National Gallery of Ireland Gallery of National Annual Report 2017 Annual Report 2017 Annual Report nationalgallery.ie Annual Report 2017 Annual Report 2017 NATIONAL GALLERY OF IRELAND 02 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Our mission is to care for, interpret, develop and showcase art in a way that makes the National Gallery of Ireland an exciting place to encounter art. We aim to provide an outstanding experience that inspires an interest in and an appreciation of art for all. We are dedicated to bringing people and their art together. 03 NATIONAL GALLERY OF IRELAND 04 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Contents Introducion 06 Chair’s Foreword 06 Director’s Review 10 Year at a Glance 2017 14 Development & Fundraising 20 Friends of the National Gallery of Ireland 26 The Reopening 15 June 2017 34 Collections & Research 51 Acquisition Highlights 52 Exhibitions & Publications 66 Conservation & Photography 84 Library & Archives 90 Public Engagement 97 Education 100 Visitor Experience 108 Digital Engagement 112 Press & Communications 118 Corporate Services 123 IT Department 126 HR Department 128 Retail 130 Events 132 Images & Licensing Department 134 Operations Department 138 Board of Governors & Guardians 140 Financial Statements 143 Appendices 185 Appendix 01 \ Acquisitions 2017 186 Appendix 02 \ Loans 2017 196 Appendix 03 \ Conservation 2017 199 05 NATIONAL GALLERY OF IRELAND Chair’s Foreword The Gallery took a major step forward with the reopening, on 15 June 2017, of the refurbished historic wings. The permanent collection was presented in a new chronological display, following extensive conservation work and logistical efforts to prepare all aspects of the Gallery and its collections for the reopening. -

Italian Painters, Critical Studies of Their Works: the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden

Italian Painters, Critical Studies of their Works: the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden. An overview of Giovanni Morelli’s attributions1 Valentina Locatelli ‘This magnificent picture-gallery [of Dresden], unique in its way, owes its existence chiefly to the boundless love of art of August III of Saxony and his eccentric minister, Count Brühl.’2 With these words the Italian art connoisseur Giovanni Morelli (Verona 1816–1891 Milan) opened in 1880 the first edition of his critical treatise on the Old Masters Picture Gallery in Dresden (hereafter referred to as ‘Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister’). The story of the Saxon collection can be traced back to the 16th century, when Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472–1553) was the court painter to the Albertine Duke George the Bearded (1500–1539). However, Morelli’s remark is indubitably correct: it was in fact not until the reign of Augustus III (1696– 1763) and his Prime Minister Heinrich von Brühl (1700–1763) that the gallery’s most important art purchases took place.3 The year 1745 marks a decisive moment in the 1 This article is the slightly revised English translation of a text first published in German: Valentina Locatelli, ‘Kunstkritische Studien über italienische Malerei: Die Galerie zu Dresden. Ein Überblick zu Giovanni Morellis Zuschreibungen’, Jahrbuch der Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Dresden, 34, (2008) 2010, 85–106. It is based upon the second, otherwise unpublished section of the author’s doctoral dissertation (in Italian): Valentina Locatelli, Le Opere dei Maestri Italiani nella Gemäldegalerie di Dresda: un itinerario ‘frühromantisch’ nel pensiero di Giovanni Morelli, Università degli Studi di Bergamo, 2009 (available online: https://aisberg.unibg.it/bitstream/10446/69/1/tesidLocatelliV.pdf (accessed September 9, 2015); from here on referred to as Locatelli 2009/II). -

Review of the Year April 2005 to March 2006 March 2005 to Year April of the Review He T

The Rothschild Archive review of the year april 2005 to march 2006 THE ARCHIVE ROTHSCHILD • REVIEW OF THE YEAR 2005 – 2006 The Rothschild Archive review of the year april 2005 to march 2006 The Rothschild Archive Trust Trustees Baron Eric de Rothschild (Chair) Emma Rothschild Lionel de Rothschild Julien Sereys de Rothschild Anthony Chapman Victor Gray Professor David Cannadine Staff Melanie Aspey (Director) Caroline Shaw (Archivist) Elaine Penn (Assistant Archivist, to June 2005) Barbra Ruperto (Assistant Archivist, from January 2006) Annette Shepherd (Secretary) The Rothschild Archive, New Court, St Swithin’s Lane, London ec4p 4du Tel: +44 (0)20 7280 5874 Fax: +44 (0)20 7280 5657 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.rothschildarchive.org Company No. 3702208 Registered Charity No. 1075340 Front cover The Temple of Rameses II at Abu Simbel, from the autochrome collection of Lionel de Rothschild (1882‒1942). 2007 marks the centenary of the public availability of the autochrome, which was the first commercially viable and successful colour process. Lionel was a keen and talented photographer whose collection of plates, a gift to The Rothschild Archive from his family, is one of the most extensive to survive in the UK. On his return from an Italian honeymoon, Lionel made a speech of thanks for their wedding gift to his parliamentary constituents of Mid Bucks revealing his dedication to his hobby and his eagerness to share its results with others: I must thank you for a very pleasant four weeks’ holiday which I have had in Italy, but I want to tell you that during those four weeks I was not idle, for I managed to take a camera with me, and I took a great many coloured photographs. -

Národní Galerie V Čr a Uk

Masarykova univerzita Ekonomicko-správní fakulta Studijní obor: Veřejná ekonomika INSTITUCIONÁLNÍ KOMPARACE KONTINENTÁLNÍHO A ANGLOAMERICKÉHO MODELU: NÁRODNÍ GALERIE V ČR A UK Institutional comparison of a continental and an Anglo- american models: National Gallery in UK and CZ Diplomová práce Vedoucí diplomové práce: Autor: Ing. František Svoboda, Ph.D. Bc. Veronika Králíková Kyjov, 2009 Jméno a příjmení autora: Veronika Králíková Název diplomové práce: Institucionální komparace kontinentálního a angloamerického modelu: Národní Galerie ČR a UK Název v angličtině: Institutional comparison of a continental and an Anglo- american models: National Gallery in UK and CZ Katedra: Veřejná ekonomika Vedoucí diplomové práce: Ing. František Svoboda, Ph.D. Rok obhajoby: 2009 Anotace Předmětem diplomové práce „Institucionální komparace kontinentálního a angloamerického modelu: Národní Galerie ČR a UK“ je analýza historického vývoje těchto institucí a jejich vzájemná komparace. První část popisuje historický vývoj a tedy i východiska, na kterých byly obě galerie vybudovány. Druhá část je věnována dnešní podobě galerií. Závěrečná kapitola je zaměřena na jejich vzájemnou komparaci. Annotation The objective of the thesis „Institutional comparison of a continental and an Anglo-american models: National Gallery in UK and CZ“ is historical development analysis and their mutual comparison. The first part describes the historical making and thus also origins of the establishment of both galleries. The second part presents their contemporary form. The closing -

Annual Report 2019/2020 Contents II President’S Foreword

Annual Report 2019/2020 Contents II President’s Foreword IV Secretary and Chief Executive’s Introduction VI Key figures IX pp. 1–63 Annual Report and Consolidated Financial Statements for the year ended 31 August 2020 XI Appendices Royal Academy of Arts Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD Telephone 020 7300 8000 royalacademy.org.uk The Royal Academy of Arts is a registered charity under Registered Charity Number 1125383 Registered as a company limited by a guarantee in England and Wales under Company Number 6298947 Registered Office: Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD © Royal Academy of Arts, 2020 Covering the period Portrait of Rebecca Salter PRA. Photo © Jooney Woodward. 1 September 2019 – Portrait of Axel Rüger. Photo © Cat Garcia. 31 August 2020 Contents I President’s I was so honoured to be elected as the Academy’s 27th President by my fellow Foreword Academicians in December 2019. It was a joyous occasion made even more special with the generous support of our wonderful staff, our loyal Friends, Patrons and sponsors. I wanted to take this moment to thank you all once again for your incredibly warm welcome. Of course, this has also been one of the most challenging years that the Royal Academy has ever faced, and none of us could have foreseen the events of the following months on that day in December when all of the Academicians came together for their Election Assembly. I never imagined that within months of being elected, I would be responsible for the temporary closure of the Academy on 17 March 2020 due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic.