Beliefs About Authentic Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

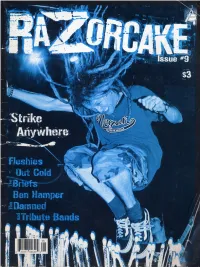

Razorcake Issue #09

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 www.razorcake.com #9 know I’m supposed to be jaded. I’ve been hanging around girl found out that the show we’d booked in her town was in a punk rock for so long. I’ve seen so many shows. I’ve bar and she and her friends couldn’t get in, she set up a IIwatched so many bands and fads and zines and people second, all-ages show for us in her town. In fact, everywhere come and go. I’m now at that point in my life where a lot of I went, people were taking matters into their own hands. They kids at all-ages shows really are half my age. By all rights, were setting up independent bookstores and info shops and art it’s time for me to start acting like a grumpy old man, declare galleries and zine libraries and makeshift venues. Every town punk rock dead, and start whining about how bands today are I went to inspired me a little more. just second-rate knock-offs of the bands that I grew up loving. hen, I thought about all these books about punk rock Hell, I should be writing stories about “back in the day” for that have been coming out lately, and about all the jaded Spin by now. But, somehow, the requisite feelings of being TTold guys talking about how things were more vital back jaded are eluding me. In fact, I’m downright optimistic. in the day. But I remember a lot of those days and that “How can this be?” you ask. -

Never Mind the Bollocks: the Punk Rock Politics of Global Communication

Review of International Studies (2008), 34, 193–210 Copyright British International Studies Association doi:10.1017/S0260210508007869 Never mind the bollocks: the punk rock politics of global communication KEVIN C. DUNN* Abstract. Largely ignored by scholars of world politics, the global punk rock scene provides a fruitful basis for exploring the multiple circuits of exchange and circulation of goods, people, and messages that moves beyond the limitations of IR. Punk can also offer new ways of thinking about international relations and communication from the lived experiences of people’s daily lives. At its core, this essay has two arguments. First, punk offers the possibility for counter-hegemonic expression within systems of global communication. Punk has simul- taneously worked within and against the hegemony of capitalist telecommunication networks, navigating an increasingly interconnected and mediated world. Second, punk is a subversive message in its own right. Focusing on punk’s Do-It-Yourself (DIY) ethos and the resource it offers for resisting the multiple forms of alienation in modern society, the story I construct here is one of agency and empowerment often overlooked by traditional IR. Introduction I am increasingly concerned about the ways that International Relations (IR) as a discipline seems unable to communicate to everyday citizens about issues of tremendous importance. I am repeatedly struck by our inability to speak to the people whose lives are affected daily by the issues we are supposed to be studying. More importantly, I am struck by how irrelevant we and our work can seem to the world’s population. In 2003, I grappled quite openly and vocally with this alienation. -

The Clash and Mass Media Messages from the Only Band That Matters

THE CLASH AND MASS MEDIA MESSAGES FROM THE ONLY BAND THAT MATTERS Sean Xavier Ahern A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2012 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Kristen Rudisill © 2012 Sean Xavier Ahern All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor This thesis analyzes the music of the British punk rock band The Clash through the use of media imagery in popular music in an effort to inform listeners of contemporary news items. I propose to look at the punk rock band The Clash not solely as a first wave English punk rock band but rather as a “news-giving” group as presented during their interview on the Tom Snyder show in 1981. I argue that the band’s use of communication metaphors and imagery in their songs and album art helped to communicate with their audience in a way that their contemporaries were unable to. Broken down into four chapters, I look at each of the major releases by the band in chronological order as they progressed from a London punk band to a globally known popular rock act. Viewing The Clash as a “news giving” punk rock band that inundated their lyrics, music videos and live performances with communication images, The Clash used their position as a popular act to inform their audience, asking them to question their surroundings and “know your rights.” iv For Pat and Zach Ahern Go Easy, Step Lightly, Stay Free. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the help of many, many people. -

Punk Lyrics and Their Cultural and Ideological Background: a Literary Analysis

Punk Lyrics and their Cultural and Ideological Background: A Literary Analysis Diplomarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Magisters der Philosophie an der Karl-Franzens Universität Graz vorgelegt von Gerfried AMBROSCH am Institut für Anglistik Begutachter: A.o. Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Hugo Keiper Graz, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 3 INTRODUCTION – What Is Punk? 5 1. ANARCHY IN THE UK 14 2. AMERICAN HARDCORE 26 2.1. STRAIGHT EDGE 44 2.2. THE NINETEEN-NINETIES AND EARLY TWOTHOUSANDS 46 3. THE IDEOLOGY OF PUNK 52 3.1. ANARCHY 53 3.2. THE DIY ETHIC 56 3.3. ANIMAL RIGHTS AND ECOLOGICAL CONCERNS 59 3.4. GENDER AND SEXUALITY 62 3.5. PUNKS AND SKINHEADS 65 4. ANALYSIS OF LYRICS 68 4.1. “PUNK IS DEAD” 70 4.2. “NO GODS, NO MASTERS” 75 4.3. “ARE THESE OUR LIVES?” 77 4.4. “NAME AND ADDRESS WITHHELD”/“SUPERBOWL PATRIOT XXXVI (ENTER THE MENDICANT)” 82 EPILOGUE 89 APPENDIX – Alphabetical Collection of Song Lyrics Mentioned or Cited 90 BIBLIOGRAPHY 117 2 PREFACE Being a punk musician and lyricist myself, I have been following the development of punk rock for a good 15 years now. You might say that punk has played a pivotal role in my life. Needless to say, I have also seen a great deal of media misrepresentation over the years. I completely agree with Craig O’Hara’s perception when he states in his fine introduction to American punk rock, self-explanatorily entitled The Philosophy of Punk: More than Noise, that “Punk has been characterized as a self-destructive, violence oriented fad [...] which had no real significance.” (1999: 43.) He quotes Larry Zbach of Maximum RockNRoll, one of the better known international punk fanzines1, who speaks of “repeated media distortion” which has lead to a situation wherein “more and more people adopt the appearance of Punk [but] have less and less of an idea of its content. -

Rebel Issue Savages the Go Go's

a magazine about female drummers TOM TOM MAGAZINE summer 2014 #18: the rebel issue rebel issue sa va ges Fay Milton Kris Ramos of STOMP Didi Negron of the Cirque du Soleil Go go’s Gina Schock Alicia Warrington ISSUE 18 | USD $6 DISPLAY SUMMER 2014 kate nash CONTRIBUTORS INSIDE issUE 18 FOUNDER/pUblishER/EDiTOR-iN-ChiEF Mindy Abovitz ([email protected]) BACKSTAGE WITH STOMP maNagiNg EDitor Melody Allegra Berger 18 REViEWs EDitor Rebecca DeRosa ([email protected]) DEsigNERs Candice Ralph, Marisa Kurk & My Nguyen CIRQUE DU SOLEIL CODERs Capisco Marketing 20 WEb maNagER Andrea Davis NORThWEsT CORREspONDENT Lisa Schonberg PLANNINGTOROCK NORThWEsT CREW Katherine Paul, Leif J. Lee, Fiona CONTRibUTiNg WRiTER Kate Ryan 24 Campbell, Kristin Sidorak la CORREspONDENTs Liv Marsico, Candace Hensen OUR FRIENDS HABIBI miami CORREspONDENT Emile Milgrim 26 bOston CORREspONDENT Kiran Gandhi baRCElONa CORREspONDENT Cati Bestard NyC DisTRO Segrid Barr ALICIA WARRINGTON/KATE NASH EUROpEaN DisTRO Max Markowsky 29 COpy EDiTOR Anika Sabin WRiTERs Chloe Saavedra, Rachel Miller, Shaina FAY FROM SAVAGES Machlus, Sarah Strauss, Emi Kariya, Jenifer Marchain, Cassandra Baim, Candace Hensen, Mar Gimeno 32 Lumbiarres, Kate Ryan, Melody Berger, Lauren Flax, JD Samson, Max Markowsky illUsTRator Maia De Saavedra TEChNiqUE WRiTERs Morgan Doctor, Fernanda Terra gina from the go-go’s Vanessa Domonique 36 phOTOgRaphERs Bex Wade, Ikue Yoshida, Chloe Aftel, Stefano Galli, Cortney Armitage, Jessica GZ, John Carlow, Annie Frame SKIP THE NEEDLE illUsTRaTORs Maia De Saavedra -

Hold Fast: Technologies of Distinction in the Australian Hardcore Music Scene

Hold Fast: Technologies of Distinction in the Australian Hardcore Music Scene Author Driver, Christopher Published 2018-12 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School School of Hum, Lang & Soc Sc DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/957 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/385865 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Hold Fast: Technologies of Distinction in the Australian Hardcore Music Scene by Christopher Driver B/Comms, MA, BA (Hons) School of Humanities, Languages and Social Science Griffith University This thesis is submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2018 1 Abstract Having emerged in the discourse of suburban American iterations of punK in the late 1970s, hardcore music has become an important cultural resource for groups around the world. The subsequent spread of the original musical tropes and development of multiple trajectories of musical and stylistic innovation have resulted in a complex and multifaceted constellation of ideas, practices and objects that now constitute the hardcore music scene. Despite its growth, scholarly discourse in the field continues to operate almost exclusively in response to what has come to be called the ‘subcultures’ framework (Clarke et al 1976). The focus has been placed on the question of whether such forms can be conceptualised in terms of coherent and subversive ideologies, effectively setting the parameters of the debate in ways that have marginalised considerations of the musical experiences of participation, and which have limited sociological attempts to comprehend the significance of hardcore music as a social force. -

A Longitudinal Content Analysis of Feminist Themes in Punk Rock

ACT LIKE A PUNK, SING LIKE A FEMINIST: A LONGITUDINAL CONTENT ANALYSIS OF FEMINIST THEMES IN PUNK ROCK SONG LYRICS, 1970-2009 Lauren E. Levine Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2015 APPROVED: Koji Fuse, Major Professor Tracy Everbach, Committee Member Gwen Nisbett, Committee Member Cory Armstrong, Chair of the Frank W. and Sue Mayborn School of Journalism Dorothy Bland, Dean of the Frank W. and Sue Mayborn School of Journalism Costas Tsatsoulis, Interim Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Levine, Lauren. E. Act Like a Punk, Sing Like a Feminist: A Longitudinal Content Analysis of Feminist Themes in Punk Rock Song Lyrics, 1970-2009. Master of Arts (Journalism), May 2015, 104 pp., 6 tables, references, 123 titles. Punk rock music has long been labeled sexist as copious media-generated accounts and reports of the genre concentrate on male artists, hyper-masculine performances, and lyrics considered to be aggressive, sexist, and misogynist. However, scholars have rarely examined punk rock music longitudinally, focusing heavily on 1980s and 1990s manifestations of the genre. Furthermore, few systematic content analyses of feminist themes in punk rock song lyrics have been conducted. The present research is a longitudinal content analysis of lyrics of 600 punk rock songs released for four decades between 1970 and 2009 to examine the prevalence of and longitudinal shifts in antiestablishment themes, the prevalence of and longitudinal shifts in sexist themes relative to feminist themes, the prevalence of and longitudinal shifts in specific feminist branches, and what factors are related to feminism. Using top-rated albums retrieved from Sputnik Music’s “Best Punk Albums” charts, systematic random sampling was applied to select 50 songs for each combination of three gender types and four decades. -

The Nature of Community in the Newfoundland Rock Underground

The nature of community in the Newfoundland rock underground. Stephen Guy Department of Art History and Communication Studies August 2004 A thesis submitted to Mc Gill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts. © Stephen Guy 2004 Library and Bibliothèque et 1+1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 0-494-06510-9 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 0-494-06510-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans loan, distribute and sell th es es le monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, électronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Hardcore Superstar Biography 2021

Biography: HARDCO RE SUPERSTAR The History Many bands play it safe – HARDCORE SUPERSTAR doesn’t. The Swedish four piece had the balls to marry two styles that grew up hating each other. We’re talking about Thrash Metal and Sleaze Rock. The former hard, aggressive and ugly, the latter catchy, melodic and decadent. So what should they name this bastard child ? --We play ‘Street Metal’ offers drummer Magnus ”Adde” Andreasson. Thrash and sleaze both come from the gutter. They wear big sneakers, they are a bit stupid and they both read pulp fiction. I can’t believe that nobody brought them together before. Early days HARDCORE SUPERSTAR did just that with the band’s fourth and eponymous album, released in 2005. But the quartet didn’t arrive overnight, rather paying its dues during a rocky but rewarding ride. The roots can be traced back to the late eighties, when Adde was talked into playing the drums by older friend and neighbour Jocke Berg. --I played the guitar and we tried our best with songs such as ‘Paranoid’ and King Diamond’s ‘Shrine’, Jocke remembers. The young teenagers, hailing from a small town just outside of Gothenburg, ended up in different bands, who in turn chose different routes from their Iron Maiden inspired beginnings. Adde opted for heavier stuff in Dorian Gray whereas the Jocke fronted Glamoury Foxx went in a glammier direction. Incidentally, Jocke took up singing thanks to one Thomas Silver, fellow guitar slinger in Glamoury Foxx. Eventually Jocke and Adde ended up together again, this time in ‘Link’, a classic rock oriented outfit with grunge leanings. -

The Guns of Brixton by the Clash (From “Punk Rock” to “Singer‐Songwriter”)

SAE Institute Amsterdam Assignment 204.2 ‐ Re‐Interpretation The Guns of Brixton by The Clash (from “Punk rock” to “Singer‐songwriter”) Student Name: Andri Hugo Runolfsson Student Number: 501791 Course Code: BRAS‐1108 Submission Date: 11 May 2009 Word Count: 1.466 Digital Version: http://www.andrihugo.com/sae/204‐2‐ri.pdf Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the BA (Honours) in Recording Arts Degree. Table of Contents Introduction 3 From one Genre to Another 4 Singer-Songwriter Music 4 Punk Rock Music 5 The Song: The Guns of Brixton 7 Original Version 7 Re-Arranging 9 Recording & Mixing 10 Conclusion 11 References 12 - 2 - Introduction In this report I will detail my work in the re-interpretation assignment, where I was asked to take an artist’s work and re- interpret it to a different style or genre. The work I chose was a song by The Clash called The Guns of Brixton from their 1979 album London Calling. The Clash was a leading band in the punk rock music genre of that time and highly influential to the punk scene as a whole. The song itself has a strong reggae influence, which is reflective of the culture around the Brixton area in the south part of London. The band fused punk rock and reggae together and the outcome was this very original sounding tune. The lyrical theme of the song mirrors feelings of discontent from the public toward heavy-handed authorities, the recession and other problems around the Brixton area at the time. I decided to make a singer-songwriter version of the song, reminiscent to the folk musicians and singer-songwriters of the late 1960s and early 1970s. -

Punk Rock's Significance in the Soviet Union and East Germany

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 4-2017 Alternative Notions of Dissent: Punk Rock’s Significance in the Soviet Union and East Germany Gabrielle E. Hibbert College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Music Performance Commons, Other German Language and Literature Commons, and the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Hibbert, Gabrielle E., "Alternative Notions of Dissent: Punk Rock’s Significance in the Soviet Union and East Germany" (2017). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1064. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1064 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Alternative Notions of Dissent: Punk Rock’s Significance in the Soviet Union and East Germany A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in German from The College of William and Mary by Gabrielle Elyse Hibbert Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ________________________________________ Bruce Campbell, Director ________________________________________ Paula Pickering ________________________________________ Sasha Prokhorov ________________________________________ Jennifer Taylor Williamsburg, VA April 24, 2017 © Copyright by Gabrielle Elyse Hibbert 2017 ABSTRACT The punk movement arrived in the late 1970s in the United States and United Kingdom, creating non-traditional and experimental ways in which to produce music. As the movement grew it developed a foundational ideology geared towards a more inclusive civil society. -

Episode #19 - Bad Religion Exposé

Episode #19 - Bad Religion Exposé Intro Welcome to Point Radio Cast. Who am I, why I'm doing this. Support Click through the site! pointradiocast.com/music.html Contact Info [email protected] Show intro - Theme Bad Religion: Through the Decades Exposé. They've been at it since 1979. Formed in LA in November or December, 1979. Greg Graffin and Brett Gurewitz have been there the whole time. They went from garage punk rock, to the punk/hardcore combo sound of today. Still at it, and still making great music! They're sort of nerd punk, and they've always had a left political angle. 1982 How Could Hell Be Any Worse? 6 Latch Key Kids Voice of God is Government Fu*k Armageddon… This is Hell, In the Night, Damned to be Free, White Trash 1983 Into the Unknown 4 Chasing the Wild Goose Losing Generation 1988 Suffer 6 Best for You Do What You Want You Are (The Government), Give You Nothing, Suffer 1989 No Control 8 Change of Ideas You No Control, I Want to Conquer the World, Anxiety, Automatic Man 1990 Against the Grain 9 Flat Earth Society Walk Away Modern Man, The Positive Aspect of Negative Thinking, Anesthesia, Faith Alone, Against the Grain, 21st Century (Digital Boy), Unacceptable 1992 Generator 8 Generator Too Much To Ask Heaven is Falling, Atomic Garden, The Answer, Fertile Cresent, Chimaera 1993 Recipe for Hate 7 American Jesus Don't Pray on Me Struck a Nerve, My Poor Friend Me, Skyscraper 1994 Stranger Than Fiction 7 Stranger Than Fiction Hooray for Me… Incomplete, Better Off Dead 1996 The Gray Race 9 Punk Rock Song Drunk Sincerity