Rock Artists' Politically Persuasive Messages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Razorcake Issue #09

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 www.razorcake.com #9 know I’m supposed to be jaded. I’ve been hanging around girl found out that the show we’d booked in her town was in a punk rock for so long. I’ve seen so many shows. I’ve bar and she and her friends couldn’t get in, she set up a IIwatched so many bands and fads and zines and people second, all-ages show for us in her town. In fact, everywhere come and go. I’m now at that point in my life where a lot of I went, people were taking matters into their own hands. They kids at all-ages shows really are half my age. By all rights, were setting up independent bookstores and info shops and art it’s time for me to start acting like a grumpy old man, declare galleries and zine libraries and makeshift venues. Every town punk rock dead, and start whining about how bands today are I went to inspired me a little more. just second-rate knock-offs of the bands that I grew up loving. hen, I thought about all these books about punk rock Hell, I should be writing stories about “back in the day” for that have been coming out lately, and about all the jaded Spin by now. But, somehow, the requisite feelings of being TTold guys talking about how things were more vital back jaded are eluding me. In fact, I’m downright optimistic. in the day. But I remember a lot of those days and that “How can this be?” you ask. -

Interview with Justin Sane from Anti-Flag

Interview with Justin Sane from Anti-Flag Photo credit: Getty Images A band that has been punk in its truest form since the early ’90s, Pittsburgh act Anti-Flag always has something to say with a fistful of rage when it comes to the government, what you see on TV and society as a whole. Anti-Flag released their ninth studio album American Spring last month to make their voices heard once again. They’ll be ripping up the stage at Simon’s 677 on Jun 19, so I chatted with frontman Justin Sane about the band’s recent solidarity with the Occupy movement, making a difference in your community and the band’s longevity. Rob Duguay: Nearly four years after the Occupy movement started back in 2011, people have either said that the movement has fizzled out or that it’s still relevant, but on an underground level. What do you think about the present state of Occupy and how much progress do you think it has made so far? Justin Sane: I think the most important part about the Occupy movement was the truths that it brought to light and the ideas that it brought to light. It’s going to take different shapes and different forms whether you attach the name Occupy to it or not. To be honest with you it doesn’t matter. What I really thought was amazing about the movement, and it had a big influence on American Spring in a lot of ways, was the notion of hope. This idea of decentralized power that Occupy brought, the idea of direct democracy and Occupy introducing the vocabulary of wealth inequality and particularly the 99% vs. -

Metal Híbrido Desde Brasil

Image not found or type unknown www.juventudrebelde.cu Metal híbrido desde Brasil Publicado: Jueves 11 octubre 2007 | 12:00:08 am. Publicado por: Juventud Rebelde La ciudad de Belo CubiertaImage not found del or CD:type unknown Dante XXI de la agrupación brasileña Sepultura. Horizonte, ubicada en el estado brasileño de Minas Gerais, fue el sitio que vio nacer, a inicios de los 80 del pasado siglo, a la banda de rock de nuestro continente que más impacto ha registrado a escala universal: el grupo Sepultura. Integrada en un primer momento por los hermanos Cavalera, Max (guitarra y voz), e Igor (batería), junto al bajista Paulo Jr., y Jairo Guedez en una segunda guitarra, la agrupación conserva total vigencia a más de 20 años de fundarse. Las principales influencias que el cuarteto reconoce en sus comienzos, provienen de gentes como Slayer, Sadus, Motörhead y Sacred Reich, quienes les ayudan a conformar un típico sonido de thrash metal. En 1985, a través del sello Cogumelo Produçoes, editan en Brasil su primer trabajo fonográfico, Bestial devastation, un disco publicado en forma de split (como se conoce a un álbum compartido con otra banda), en compañía de los también brasileños de Overdose. El éxito del material sorprende a muchos y así, Cogumelo Produçoes se asocia a Road Runner Records, para sacar al mercado, en 1986, el primer LP íntegro con música de Sepultura, Morbid visions, valorado al paso del tiempo como un clásico del universo metalero, gracias a cortes como War, Crucifixion y, en especial, Troops of doom, tema que pasó a ser una suerte de himno para la banda. -

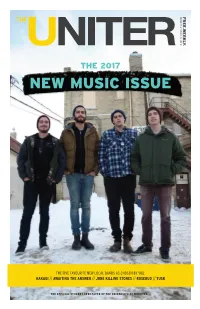

New Music Issue

FREE.WEEKLY. VOLUME VOLUME 71 // ISSUE 16 // JAN 19 THE 2017 NEW MUSIC ISSUE THE FIVE FAVOURITE NEW LOCAL BANDS AS CHOSEN BY YOU: KAKAGI // AWAITING THE ANSWER // JUNE KILLING STONES // ROSEBUD // TUSK THE OFFICIAL STUDENT NEWSPAPER OF THE UNIVERSITY OF WINNIPEG CDI_Uniter_Winnipeg_generic.pdf 1 2017-01-03 1:02 PM ASK ABOUT OUR EVENING CLASSES THAT FIT YOUR SCHEDULE C M a trained Y CM MY professional CY Prepare for an exciting new career in one of our accelerated CMY professional programs and be job ready in less than a year! K Get the skills and experience you need to excel in your field and create your own future. Apply today! 1.800.675.4392 NEWCAREER.CDICOLLEGE.CA Symbol of Courage We’d love to tell you more. Special offer: admission only $5 until January 31, 2017 humanrights.ca #AtCMHR THE UNITER // JANUARY 19, 2017 3 ON THE COVER Kakagi, winners of this year's Uniter Fiver, will headline the showcase at The Good Will Social Club on Jan. 19. SHOW TIME! Before I even get into all the awesome content we’ve gathered together for you in this issue, here’s a final shameless plug for our Uniter Fiver showcase. We’ve got a really great lineup for you on Jan. 19 at The Good Will Social Club: Kakagi, June Killing Stones, Tusk, Rosebud and Awaiting the Answer. Doors are at 8 p.m., show is at 9 p.m., and cover is $10 or $5 with student ID. Come join us and support new local music in Winnipeg! Beyond the show, we’ve got some extended music coverage within these pages for our annual New Music Issue. -

Razorcake Issue

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 #19 www.razorcake.com ight around the time we were wrapping up this issue, Todd hours on the subject and brought in visual aids: rare and and I went to West Hollywood to see the Swedish band impossible-to-find records that only I and four other people have RRRandy play. We stood around outside the club, waiting for or ancient punk zines that have moved with me through a dozen the show to start. While we were doing this, two young women apartments. Instead, I just mumbled, “It’s pretty important. I do a came up to us and asked if they could interview us for a project. punk magazine with him.” And I pointed my thumb at Todd. They looked to be about high-school age, and I guess it was for a About an hour and a half later, Randy took the stage. They class project, so we said, “Sure, we’ll do it.” launched into “Dirty Tricks,” ripped right through it, and started I don’t think they had any idea what Razorcake is, or that “Addicts of Communication” without a pause for breath. It was Todd and I are two of the founders of it. unreal. They were so tight, so perfectly in time with each other that They interviewed me first and asked me some basic their songs sounded as immaculate as the recordings. On top of questions: who’s your favorite band? How many shows do you go that, thought, they were going nuts. Jumping around, dancing like to a month? That kind of thing. -

Never Mind the Bollocks: the Punk Rock Politics of Global Communication

Review of International Studies (2008), 34, 193–210 Copyright British International Studies Association doi:10.1017/S0260210508007869 Never mind the bollocks: the punk rock politics of global communication KEVIN C. DUNN* Abstract. Largely ignored by scholars of world politics, the global punk rock scene provides a fruitful basis for exploring the multiple circuits of exchange and circulation of goods, people, and messages that moves beyond the limitations of IR. Punk can also offer new ways of thinking about international relations and communication from the lived experiences of people’s daily lives. At its core, this essay has two arguments. First, punk offers the possibility for counter-hegemonic expression within systems of global communication. Punk has simul- taneously worked within and against the hegemony of capitalist telecommunication networks, navigating an increasingly interconnected and mediated world. Second, punk is a subversive message in its own right. Focusing on punk’s Do-It-Yourself (DIY) ethos and the resource it offers for resisting the multiple forms of alienation in modern society, the story I construct here is one of agency and empowerment often overlooked by traditional IR. Introduction I am increasingly concerned about the ways that International Relations (IR) as a discipline seems unable to communicate to everyday citizens about issues of tremendous importance. I am repeatedly struck by our inability to speak to the people whose lives are affected daily by the issues we are supposed to be studying. More importantly, I am struck by how irrelevant we and our work can seem to the world’s population. In 2003, I grappled quite openly and vocally with this alienation. -

Trio Solido Parte 3, Ucd180

Pratica di Claudio Negro Il trio solido - UcD180 Terza parte Il menu di quest’ultima puntata prevede l’amplificatore più potente dei tre trattati, ovvero l’UcD180ST della olandese Hypex, e il suo alimentatore, il tutto condito con una prova d’ascolto comparativa. Il terzo finale che vi proponiamo (Figura marchio americano) racconta che il prototi- non se ne parla più), principalmente per 01) appartiene alla famiglia degli amplifica- po iniziò a funzionare solo la sera prima alcune limitazioni di risposta in frequenza. tori a commutazione (anche nota come dell’inaugurazione del CES, e con il display Difatti, al variare del carico la risposta tipi- PWM, classe D, classe T e digitale, a spento, visto che introduceva dei ticchettii ca di un amplificatore a commutazione pre- seconda dell’implementazione), topologia nel suono; fatto sta che l’apparecchio entrò senta enfasi o tagli alle alte frequenze, relativamente recente, visto che già la si fisicamente nella sala Infinity solo un’ora tanto che il loro uso è stato relegato princi- usava nel secondo dopoguerra, e più che prima dall’apertura dei cancelli della fiera, palmente ai sub woofer attivi e al mondo altro conosciuta per l’alta efficienza di cui è ma riuscì a suonare senza problemi per professionale, dove le dimensioni contenu- capace. L’ingresso della classe D nel tutti e quattro i giorni della manifestazione. te, le basse perdite e le ridotte richieste di mondo dell’audio risale alla fine del 1964 Subito dopo il CES, la Infinity lo iniziò a dissipazione tipiche di questa topologia, con il kit X-10 della Sinclair Radionics, pro- produrre e vendere con il nome di SWAMP sono come una manna caduta dal cielo. -

OP 323 Sex Tips.Indd

BY PAUL MILES Copyright © 2010 Paul Miles This edition © 2010 Omnibus Press (A Division of Music Sales Limited) Cover and book designed by Fresh Lemon ISBN: 978.1.84938.404.9 Order No: OP 53427 The Author hereby asserts his/her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with Sections 77 to 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages. Exclusive Distributors Music Sales Limited, 14/15 Berners Street, London, W1T 3LJ. Music Sales Corporation, 257 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10010, USA. Macmillan Distribution Services, 56 Parkwest Drive Derrimut, Vic 3030, Australia. Printed by: Gutenberg Press Ltd, Malta. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Visit Omnibus Press on the web at www.omnibuspress.com For more information on Sex Tips From Rock Stars, please visit www.SexTipsFromRockStars.com. Contents Introduction: Why Do Rock Stars Pull The Hotties? ..................................4 The Rock Stars ..........................................................................................................................................6 Beauty & Attraction .........................................................................................................................18 Clothing & Lingerie ........................................................................................................................35 -

“Punk Rock Is My Religion”

“Punk Rock Is My Religion” An Exploration of Straight Edge punk as a Surrogate of Religion. Francis Elizabeth Stewart 1622049 Submitted in fulfilment of the doctoral dissertation requirements of the School of Language, Culture and Religion at the University of Stirling. 2011 Supervisors: Dr Andrew Hass Dr Alison Jasper 1 Acknowledgements A debt of acknowledgement is owned to a number of individuals and companies within both of the two fields of study – academia and the hardcore punk and Straight Edge scenes. Supervisory acknowledgement: Dr Andrew Hass, Dr Alison Jasper. In addition staff and others who read chapters, pieces of work and papers, and commented, discussed or made suggestions: Dr Timothy Fitzgerald, Dr Michael Marten, Dr Ward Blanton and Dr Janet Wordley. Financial acknowledgement: Dr William Marshall and the SLCR, The Panacea Society, AHRC, BSA and SOCREL. J & C Wordley, I & K Stewart, J & E Stewart. Research acknowledgement: Emily Buningham @ ‘England’s Dreaming’ archive, Liverpool John Moore University. Philip Leach @ Media archive for central England. AHRC funded ‘Using Moving Archives in Academic Research’ course 2008 – 2009. The 924 Gilman Street Project in Berkeley CA. Interview acknowledgement: Lauren Stewart, Chloe Erdmann, Nathan Cohen, Shane Becker, Philip Johnston, Alan Stewart, N8xxx, and xEricx for all your help in finding willing participants and arranging interviews. A huge acknowledgement of gratitude to all who took part in interviews, giving of their time, ideas and self so willingly, it will not be forgotten. Acknowledgement and thanks are also given to Judy and Loanne for their welcome in a new country, providing me with a home and showing me around the Bay Area. -

Breast Cancer Research at CSP by Nathan Lechband

October 16, 2006 Volume 42 Issue 2 Breast Cancer Research At CSP by Nathan Lechband "My grandmother was diagnosed with breast cancer last spring," said Kyle Warren. "My sister was 23 and had a lumpectomy (a removal of a be- nign tumor in the breast) right before. M y whole family was dealing with breast cancer issues at once." Two years ago Kyle attended a topics sem- inar in which Concordia biology professor Amy Gort introduced him to the possibilit y of breast cancer research. Kyle will be helping with breast cancer research that has already been taking place at Concordia for the past two years. "This semester we're writing the proposal and next semester well delve into the actual research," he said.z Most studies of cancer cell lines are done at large research institutions or privately funded labs. According to the National Cancer Institute cancer research projects received a total of $4.83 billion in 2005. Of those funds $560.1 million went to breast cancer projects. Concordia's can- cer research project has moved forward without Research team obserVing cells in the back room of a classroom in the Science building. the benefit of any direct federal funds. photo by Hannah Dorow Concordia's breast cancer cell lines were cul- tured from breast cancer tumor cells from five for comment. million times. The DNA is then placed on an different patients. These cell lines, along with The researchers here at Concordia are attempt- electrically charged gel in which the different several different cervical cancer cell lines, were ing to identify and characterize human papillo- DNA sequences are separated by size and tested obtained from Dr. -

Rebirth Billy Graziadei

THE REBIRTHOF z z RD u HAZA b BIO INTERVIEW WITH BILLY GRAZIADEI by Daniel Alleva the personal issues with us, and with I recently spoke with Biohazard’s Billy Fuck itstand up, and what’s going on around the world. Graziadei about his band’s new album, “‘ One of the things I was thinking about Reborn In Defiance , and together, we t of in relation to hardcore music, thrash talked at length on many topics, from how let s go. It s par music, death metal, etc., is there a the sudden departure of bassist/co-vocalist ’ ’ ’ universal adversary that that music, Evan Seinfeld made him feel, to the fight our lyrics and part of on principle, stands in opposition to? against conformity that unifies underground The one word that pops out in my head music. Billy is the real deal. He spoke from way of life. is conformity. My brother told me this story his heart and didn’t give you any bullshit. our ” once. He was riding in the car with my old That spirit can be heard all throughout man and they were at a red light. These Reborn In Defiance , a record that certainly kids in sk ateboards came whizzing past, lets everyone know that Biohazard is Well, I know you guys were all back has cleared a little bit —I haven’t told many about life and obstacles is the fear of it. If and you know —they had patches on their back—not looking to fuck around, or beat together, and you were making a record, people this —but at the time, I was pissed.