Screamed Poetry: Rock in Poland's Last Decade of Communism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sounds of War and Peace: Soundscapes of European Cities in 1945

10 This book vividly evokes for the reader the sound world of a number of Eu- Renata Tańczuk / Sławomir Wieczorek (eds.) ropean cities in the last year of the Second World War. It allows the reader to “hear” elements of the soundscapes of Amsterdam, Dortmund, Lwów/Lviv, Warsaw and Breslau/Wrocław that are bound up with the traumatising experi- ences of violence, threats and death. Exploiting to the full methodologies and research tools developed in the fields of sound and soundscape studies, the Sounds of War and Peace authors analyse their reflections on autobiographical texts and art. The studies demonstrate the role urban sounds played in the inhabitants’ forging a sense of 1945 Soundscapes of European Cities in 1945 identity as they adapted to new living conditions. The chapters also shed light on the ideological forces at work in the creation of urban sound space. Sounds of War and Peace. War Sounds of Soundscapes of European Cities in Volume 10 Eastern European Studies in Musicology Edited by Maciej Gołąb Renata Tańczuk is a professor of Cultural Studies at the University of Wrocław, Poland. Sławomir Wieczorek is a faculty member of the Institute of Musicology at the University of Wrocław, Poland. Renata Tańczuk / Sławomir Wieczorek (eds.) · Wieczorek / Sławomir Tańczuk Renata ISBN 978-3-631-75336-1 EESM 10_275336_Wieczorek_SG_A5HC globalL.indd 1 16.04.18 14:11 10 This book vividly evokes for the reader the sound world of a number of Eu- Renata Tańczuk / Sławomir Wieczorek (eds.) ropean cities in the last year of the Second World War. It allows the reader to “hear” elements of the soundscapes of Amsterdam, Dortmund, Lwów/Lviv, Warsaw and Breslau/Wrocław that are bound up with the traumatising experi- ences of violence, threats and death. -

Financial Crime in the Operational Work of the State Security Service Until 1956 – Lower Silesian Perspective

STUdIA HISTORIAE OECONOMICAE UAM Vol. 34 Poznań 2016 zhg.amu.edu.pl/sho Robert K l e m e n t o w s k i (Institute of National Remembrance/University of Wrocław, Wrocław) FINANCIAL CRIME IN THE OPERATIONAL WORK OF THE STATE SECURITY SERVICE UNTIL 1956 – LOWER SILESIAN PERSPECTIVE Nationalization and the introduction of state-controlled economy led to the emergence of abnormal social phenomena, including system-specific crimes. Economic transformations were the foundation of the systemic revolution carried out in the first decade after the Second World War, therefore they were the subject of interest for the Ministry of Public Security. That is why financial crimes were treated just like political crimes, which was also justified by legal provisions, as no specific definition of this type of crime existed. This allowed the authorities (secret police, prosecutor’s office, courts, media) to interpret the events according to their will and current political needs, and, as a result, to administer various overt or covert repressions (death penalty, imprisonment, forced cooperation with the secret police). Keywords: financial crime, security services, Lower Silesia. doi:10.1515/sho-2016-0008 INTRODUCTION The problem of financial crime in the first years following the end of the Second World War was not a particularly interesting subject for his- torians. To some extent this is understandable, as political issues were of prime concern, including the creation of the Polish Workers Party/Polish United Worker’s Party administration or the elimination of both real and sham opposition. The longer the research on this subject is conducted, the clearer it becomes that the bedrocks of the new system were not actually its repressive nature or single-party rule, but the permanent transforma- tion of the economic system. -

Bo Diddley to Peform ------— at the Chili Factory Due to an Unfortunate Oversight, the Last Saturday, Feb

'«£'SS’£X'i«55>*S>?? ?f»& V •V ftv ,<> *^e<?v ^ o|b | ^A*^, °il^ li*i«l;|| Ju'.iitv S J w S S i k # I w 5 % \ S S f e M l m & ig m \ •ft;6' S ^ e * K&@£sfcrfg££ \ * e >te ’ «&«K t£& b 'V l J k 0 m $ L '^ fs ; ig $ it i > 9 4 3 &&&&aV ^''^ j r a g ^ S « * * » * ° * t* % y < e ^ V \ e V ^ w s ^ F T s m \ l i S ^ ^ H ® 0 $ ^ m S m m U S S U M “Okay, what is it! lean see th a t loo your face again»99 —mi ■! v^r— \\ ✓ / e W m m M A ^ k 2A Thursday, February 21,1985 Daily Nexus Jean-Luc Ponty Departing from Perfection Jean-Luc Ponty started his recent concert with a bit of dramatic suspense. As the curtains opened last Wednesday night he stood with no violin, but instead playing keyboards. It wasn’t until he picked up his unusually shaped electric violin that I felt completely involved in his music. There was satisfaction in seeing Ponty perform after hearing what I always thought was possibly a violin but was never quite sure in many cases. Being able to see Ponty playing his violin gave a sense of the inventiveness and originality of his music. Armed also with a full backup band, Ponty • was very successful in presenting music that seemed to be 8 much less effective on his latest albums. j: The difference between Ponty’s performance of the title track “Open Mind” the night of the concert as opposed to • the recording was that there were people playing the 2 drums, bass and guitar instead of computers. -

In Their Own Words: Voices of Jihad

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as CHILD POLICY a public service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION Jump down to document ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT 6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and PUBLIC SAFETY effective solutions that address the challenges facing SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY the public and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Support RAND TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Purchase this document WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Learn more about the RAND Corporation View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND monographs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. in their own words Voices of Jihad compilation and commentary David Aaron Approved for public release; distribution unlimited C O R P O R A T I O N This book results from the RAND Corporation's continuing program of self-initiated research. -

Lecture 27 Epilogue How Far Does the Past Dominate Polish Politics Today? 'Choose the Future' Election Slogan of Alexander K

- 1 - Lecture 27 Epilogue How far does the past dominate Polish politics today? ‘Choose the future’ Election slogan of Alexander Kwaśniewski in 1996. ‘We are today in the position of Andrzej Gołota: after seven rounds, we are winning on points against our historical fatalism. As rarely in our past - today almost everything depends on us ourselves... In the next few years, Poland’s fate for the succeeding half- century will be decided. And yet Poland has the chance - like Andrzej Gołota, to waste its opportunity. We will not enter NATO of the European Union if we are a country beset by a domestic cold war, a nation so at odds with itself that one half wants to destroy the other. Adam Michnik, ‘Syndrom Gołoty’, Gazeta Świąteczna, 22 December 1996 ‘I do not fear the return of communism, but there is a danger of new conflicts between chauvinism and nationalist extremism on the one hand and tolerance, liberalism and Christian values on the other’ Władysław Bartoszewski on the award to him of the Heinrich Heine prize, December 1996 1. Introduction: History as the Means for Articulating Political Orientations In Poland, as in most countries which have been compelled to struggle to regain their lost independence, an obsessive involvement with the past and a desire to derive from it lessons of contemporary relevance have long been principal characteristics of the political culture. Polish romantic nationalism owed much to Lelewel’s concept of the natural Polish predilection for democratic values. The Polish nation was bound, he felt, to struggle as ‘ambassador to humanity’ and, through its suffering, usher in an era on universal liberty. -

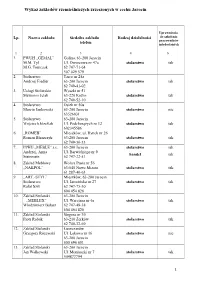

Wykaz Zakładów Rzemieślniczych Zrzeszonych W Cechu Jarocin

Wykaz zakładów rzemie ślniczych zrzeszonych w cechu Jarocin Uprawnienia Lp. Nazwa zakładu Siedziba zakładu Rodzaj działalno ści do szkolenia pracowników telefon młodocianych 1 2 3 4 6 1. PWUH „GEMAL” Golina, 63-200 Jarocin M.M. Tyl Ul. Dworcowa nr 47a stolarstwo tak M.G. Tomczak 62 747-71-64 507 029 579 2. Stolarstwo Tarce nr 25a Andrzej Fiedler 63-200 Jarocin stolarstwo tak 62 749-41-02 3. Usługi Stolarskie Wyszki nr 51 Sławomir Jelak 63-220 Kotlin stolarstwo tak 62 740-52-10 4. Stolarstwo Osiek nr 50a Marcin Jankowski 63-200 Jarocin stolarstwo nie 63526031 5. Stolarstwo 63-200 Jarocin Wojciech Józefiak Ul. Podchor ąż ych nr 12 stolarstwo tak 602345586 6. „ROMEB” Mieszków, ul. Rynek nr 26 Roman Błaszczyk 63-200 Jarocin stolarstwo tak 62 749-30-33 7. PPHU „MEBLE” s.c. 63-200 Jarocin stolarstwo tak Andrzej, Anna Ul. Barwickiego nr 9 handel tak Steinmetz 62 747-22-51 8. Zakład Meblowy Wolica Pusta nr 56 „NAKPOL” 63-040 Nowe Miasto stolarstwo tak 61 287-40-63 9. „ART.-STYL” Mieszków, 63-200 Jarocin Stolarstwo Ul. Jaroci ńska nr 27 stolarstwo tak Rafał Szik 62 747-75-50 604 454 826 10. Zakład Stolarski 63-200 Jarocin „MEBLEX” Ul. Warciana nr 6a stolarstwo tak Włodzimierz Bałasz 62 747-48-38 604 454 826 11. Zakład Stolarski St ęgosz nr 30 Piotr Robak 63-210 Żerków stolarstwo tak 62 740-32-69 12. Zakład Stolarski Łuszczanów Grzegorz Ró żewski Ul. Ł ąkowa nr 16 stolarstwo nie 63-200 Jarocin 600 696 651 13. Zakład Stolarski 63-200 Jarocin Jan Wałkowski Ul. -

Katyn Massacre

Katyn massacre This article is about the 1940 massacre of Polish officers The Katyn massacre, also known as the Katyn Forest massacre (Polish: zbrodnia katyńska, 'Katyń crime'), was a mass murder of thousands of Polish military officers, policemen, intellectuals and civilian prisoners of war by Soviet NKVD, based on a proposal from Lavrentiy Beria to execute all members of the Polish Officer Corps. Dated March 5, 1940, this official document was then approved (signed) by the entire Soviet Politburo including Joseph Stalin and Beria. The number of victims is estimated at about 22,000, the most commonly cited number being 21,768. The victims were murdered in the Katyn Forest in Russia, the Kalinin (Tver) and Kharkov prisons and elsewhere. About 8,000 were officers taken prisoner during the 1939 Soviet invasion of Poland, the rest being Poles arrested for allegedly being "intelligence agents, gendarmes, saboteurs, landowners, factory owners, lawyers, priests, and officials." Since Poland's conscription system required every unexempted university graduate to become a reserve officer, the Soviets were able to round up much of the Polish intelligentsia, and the Jewish, Ukrainian, Georgian and Belarusian intelligentsia of Polish citizenship. The "Katyn massacre" refers to the massacre at Katyn Forest, near Katyn-Kharkiv-Mednoye the villages of Katyn and Gnezdovo (ca. 19 km west of Smolensk, memorial Russia), of Polish military officers in the Kozelsk prisoner-of-war camp. This was the largest of the simultaneous executions of prisoners of war from geographically distant Starobelsk and Ostashkov camps, and the executions of political prisoners from West Belarus and West Ukraine, shot on Stalin's orders at Katyn Forest, at the NKVD headquarters in Smolensk, at a Smolensk slaughterhouse, and at prisons in Kalinin (Tver), Kharkov, Moscow, and other Soviet cities. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1984

Vol. Ul No. 38 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 16,1984 25 cents House committee sets hearings for Faithful mourn Patriarch Josyf famine study bill WASHINGTON - The House Sub committee on International Operations has set October 3 as the date for hearings on H.R. 4459, the bill that would establish a congressional com mission to investigate the Great Famine in Ukraine (1932-33), reported the Newark-based Americans for Human Rights in Ukraine. The hearings will be held at 2 p.m. in Room 2200 in the Sam Rayburn House Office Building. The chairman of the subcommittee, which is part of the Foreign Affairs Committee, is Rep. Dan Mica (D-Fla.). The bill, which calls for the formation of a 21-member investigative commission to study the famine, which killed an esUmated ^7.^ million UkrdtftUllk. yif ітіІДЯДІШ'' House last year by Rep. James Florio (D-N.J.). The Senate version of the measure, S. 2456, is currently in the Foreign Rela tions Committee, which held hearings on the bill on August I. The committee is expected to rule on the measure this month. In the House. H.R. 4459 has been in the Subcommittee on International Operations and the Subcommittee on Europe and the Middle East since last November. According to AHRU, which has lobbied extensively on behalf of the legislation, since one subcommittee has Marta Kolomaysls scheduled hearings, the other, as has St. George Ukrainian Catholic Church in New Yoric City and parish priests the Revs, Leo Goldade and Taras become custom, will most likely waive was but one of the many Ulcrainian Catholic churches Prokopiw served a panakhyda after a liturgy at St. -

Lithuanians and Poles Against Communism After 1956. Parallel Ways to Freedom?

Lithuanians and Poles against Communism after 1956. Parallel Ways to Freedom? The project has been co-financed by the Department of Public and Cultural Diplomacy of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs within the competition ‘Cooperation in the field of public diplomacy 2013.’ The publication expresses only the views of the author and must not be identified with the official stance of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The book is available under the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0, Poland. Some rights have been reserved to the authors and the Faculty of International and Po- litical Studies of the Jagiellonian University. This piece has been created as a part of the competition ‘Cooperation in the Field of Public Diplomacy in 2013,’ implemented by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 2013. It is permitted to use this work, provided that the above information, including the information on the applicable license, holders of rights and competition ‘Cooperation in the field of public diplomacy 2013’ is included. Translated from Polish by Anna Sekułowicz and Łukasz Moskała Translated from Lithuanian by Aldona Matulytė Copy-edited by Keith Horeschka Cover designe by Bartłomiej Klepiński ISBN 978-609-8086-05-8 © PI Bernardinai.lt, 2015 © Jagiellonian University, 2015 Lithuanians and Poles against Communism after 1956. Parallel Ways to Freedom? Editet by Katarzyna Korzeniewska, Adam Mielczarek, Monika Kareniauskaitė, and Małgorzata Stefanowicz Vilnius 2015 Table of Contents 7 Katarzyna Korzeniewska, Adam Mielczarek, Monika Kareniauskaitė, Małgorzata -

Heartoflove.Pdf

Contents Intro............................................................................................................................................................. 18 Indian Mystics ............................................................................................................................................. 20 Brahmanand ............................................................................................................................................ 20 Palace in the sky .................................................................................................................................. 22 The Miracle ......................................................................................................................................... 23 Your Creation ...................................................................................................................................... 25 Prepare Yourself .................................................................................................................................. 27 Kabir ........................................................................................................................................................ 29 Thirsty Fish .......................................................................................................................................... 30 Oh, Companion, That Abode Is Unmatched ....................................................................................... 31 Are you looking -

Stan Magazynu Caĺ†Oĺıäƒ Lp Cd Sacd Akcesoria.Xls

CENA WYKONAWCA/TYTUŁ BRUTTO NOŚNIK DOSTAWCA ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - AT FILLMORE EAST 159,99 SACD BERTUS ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - AT FILLMORE EAST (NUMBERED 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - BROTHERS AND SISTERS (NUMBE 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - EAT A PEACH (NUMBERED LIMIT 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - IDLEWILD SOUTH (GOLD CD) 129,99 CD GOLD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - THE ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND (N 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ASIA - ASIA 179,99 SACD BERTUS BAND - STAGE FRIGHT (HYBRID SACD) 89,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BAND, THE - MUSIC FROM BIG PINK (NUMBERED LIMITED 89,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BAND, THE - THE LAST WALTZ (NUMBERED LIMITED EDITI 179,99 2 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BASIE, COUNT - LIVE AT THE SANDS: BEFORE FRANK (N 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BIBB, ERIC - BLUES, BALLADS & WORK SONGS 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC - JUST LIKE LOVE 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC - RAINBOW PEOPLE 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC & NEEDED TIME - GOOD STUFF 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC & NEEDED TIME - SPIRIT & THE BLUES 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BLIND FAITH - BLIND FAITH 159,99 SACD BERTUS BOTTLENECK, JOHN - ALL AROUND MAN 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 CAMEL - RAIN DANCES 139,99 SHMCD BERTUS CAMEL - SNOW GOOSE 99,99 SHMCD BERTUS CARAVAN - IN THE LAND OF GREY AND PINK 159,99 SACD BERTUS CARS - HEARTBEAT CITY (NUMBERED LIMITED EDITION HY 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY CHARLES, RAY - THE GENIUS AFTER HOURS (NUMBERED LI 99,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY CHARLES, RAY - THE GENIUS OF RAY CHARLES (NUMBERED 129,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY -

Beats of Freedom – Zew Wolności, Opracowanie: Artur Brzeziński

NCK_BoF_okl_druk.pdf 1 10-03-01 15:05 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Untitled-1 1 2010-03-01 14:25:16 4. Przewodnik dla nauczycieli do filmu Leszka Gnoińskiego i Wojciecha Słoty Beats of Freedom – Zew wolności, opracowanie: Artur Brzeziński, Centrum Projektów Edukacyjnych 12. Dziwny jest ten świat, autor: Chris Salewicz 16. Punk vs. System, autor: Grzegorz Brzozowicz 21. Lata 80. w pięciu odsłonach, autor: Maciej Chmiel 25. Złote lata festiwalu w Jarocinie – 1980–1986, autor: Robert Jarosz 31. Nasze ZOO. Rola hipopotama w muzyce rockowej PRL-u, autor: Mirosław Makowski 35. Punkławy, autor: Sławek Pakos 38. Co mógł rock, autor: Mirosław Pęczak 41. Fonografia w komuniźmie, autor: Hirek Wrona 2 Beats of Freedom – Zew wolności To porywający film o narodzinach rocka w Polsce. Barwne wspomnie- W filmie występują m.in.: Marek Niedźwiecki, Krzysztof Skiba, Jurek nia kultowych muzyków i ich zaskakujące zwierzenia sprawiają, że film Owsiak, Kazik Staszewski (Kult), Muniek Staszczyk (T.Love), Kora Jac- ten na długo zapada w pamięć. Daj się porwać ostremu brzmieniu i fa- kowska (Maanam), Tomek Lipiński (Tilt i Brygada Kryzys), Krzysztof scynującym, nieocenzurowanym historiom. Otwórz oczy i posłuchaj jak Grabowski (Dezerter). polski rock tworzył historię. „Rock był jedną z ważniejszych dziedzin, które mnie W czasach, gdy życie w Polsce kontrolował reżim, muzy- ukształtowały, teraz stał się ważnym elementem mojego ka stała się fenomenem o kolosalnej sile rażenia. „Żela- życia. Tym filmem chciałem oddać hołd ludziom, którzy zna kurtyna” nie była w stanie zatrzymać rocka, a młodzi wpłynęli na moje postrzeganie świata, a następnym po- ludzie, dzięki tej muzyce, odnaleźli swoją przestrzeń wol- koleniom przypomnieć, czym ta muzyka była kiedyś i czym ności.