The Nature of Community in the Newfoundland Rock Underground

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Razorcake Issue #09

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 www.razorcake.com #9 know I’m supposed to be jaded. I’ve been hanging around girl found out that the show we’d booked in her town was in a punk rock for so long. I’ve seen so many shows. I’ve bar and she and her friends couldn’t get in, she set up a IIwatched so many bands and fads and zines and people second, all-ages show for us in her town. In fact, everywhere come and go. I’m now at that point in my life where a lot of I went, people were taking matters into their own hands. They kids at all-ages shows really are half my age. By all rights, were setting up independent bookstores and info shops and art it’s time for me to start acting like a grumpy old man, declare galleries and zine libraries and makeshift venues. Every town punk rock dead, and start whining about how bands today are I went to inspired me a little more. just second-rate knock-offs of the bands that I grew up loving. hen, I thought about all these books about punk rock Hell, I should be writing stories about “back in the day” for that have been coming out lately, and about all the jaded Spin by now. But, somehow, the requisite feelings of being TTold guys talking about how things were more vital back jaded are eluding me. In fact, I’m downright optimistic. in the day. But I remember a lot of those days and that “How can this be?” you ask. -

Rill^ 1980S DC

rill^ 1980S DC rii£!St MTEVOLUTIO N AND EVKllMSTINO KFFK Ai\ liXTEiniKM^ WITH GUY PICCIOTTO BY KATni: XESMITII, IiV¥y^l\^ IKWKK IXSTRUCTOU: MR. HiUfiHT FmAL DUE DATE: FEBRUilRY 10, SOOO BANNED IN DC PHOTOS m AHEcoorts FROM THE re POHK UMOEAG ROUND pg-ssi OH t^€^.S^ 2006 EPISCOPAL SCHOOL American Century Oral History Project Interviewee Release Form I, ^-/ i^ji^ I O'nc , hereby give and grant to St. Andrew's (interviewee) Episcopal School llie absolute and unqualified right to the use ofmy oral history memoir conducted by KAi'lL I'i- M\-'I I on / // / 'Y- .1 understand that (student interviewer) (date) the purpose of (his project is to collect audio- and video-taped oral histories of first-hand memories ofa particular period or event in history as part of a classroom project (The American Century Project). 1 understand that these interviews (tapes and transcripts) will be deposited in the Saint Andrew's Episcopal School library and archives for the use by ftiture students, educators and researchers. Responsibility for the creation of derivative works will be at the discretion of the librarian, archivist and/or project coordinator. I also understand that the tapes and transcripts may be used in public presentations including, but not limited to, books, audio or video doe\imcntaries, slide-tape presentations, exhibits, articles, public performance, or presentation on the World Wide Web at t!ic project's web site www.americaiicenturyproject.org or successor technologies. In making this contract I understand that I am sharing with St. Andrew's Episcopal School librai-y and archives all legal title and literary property rights which i have or may be deemed to have in my inten'iew as well as my right, title and interest in any copyright related to this oral history interview which may be secured under the laws now or later in force and effect in the United States of America. -

La Fugazi Live Series Sylvain David

Document generated on 10/01/2021 9:37 p.m. Sens public « Archive-it-yourself » La Fugazi Live Series Sylvain David (Re)constituer l’archive Article abstract 2016 Fugazi, one of the most respected bands of the American independent music scene, recently posted almost all of its live performances online, releasing over URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1044387ar 800 recordings made between 1987 and 2003. Such a project is atypical both by DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1044387ar its size, rock groups being usually content to produce one or two live albums during the scope of their career, and by its perspective, Dischord Records, an See table of contents independent label, thus undertaking curatorial activities usually supported by official cultural institutions such as museums, libraries and universities. This approach will be considered here both in terms of documentation, the infinite variations of the concerts contrasting with the arrested versions of the studio Publisher(s) albums, and of the musical canon, Fugazi obviously wishing, by the Département des littératures de langue française constitution of this digital archive, to contribute to a parallel rock history. ISSN 2104-3272 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article David, S. (2016). « Archive-it-yourself » : la Fugazi Live Series. Sens public. https://doi.org/10.7202/1044387ar Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) Sens-Public, 2016 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. -

Never Mind the Bollocks: the Punk Rock Politics of Global Communication

Review of International Studies (2008), 34, 193–210 Copyright British International Studies Association doi:10.1017/S0260210508007869 Never mind the bollocks: the punk rock politics of global communication KEVIN C. DUNN* Abstract. Largely ignored by scholars of world politics, the global punk rock scene provides a fruitful basis for exploring the multiple circuits of exchange and circulation of goods, people, and messages that moves beyond the limitations of IR. Punk can also offer new ways of thinking about international relations and communication from the lived experiences of people’s daily lives. At its core, this essay has two arguments. First, punk offers the possibility for counter-hegemonic expression within systems of global communication. Punk has simul- taneously worked within and against the hegemony of capitalist telecommunication networks, navigating an increasingly interconnected and mediated world. Second, punk is a subversive message in its own right. Focusing on punk’s Do-It-Yourself (DIY) ethos and the resource it offers for resisting the multiple forms of alienation in modern society, the story I construct here is one of agency and empowerment often overlooked by traditional IR. Introduction I am increasingly concerned about the ways that International Relations (IR) as a discipline seems unable to communicate to everyday citizens about issues of tremendous importance. I am repeatedly struck by our inability to speak to the people whose lives are affected daily by the issues we are supposed to be studying. More importantly, I am struck by how irrelevant we and our work can seem to the world’s population. In 2003, I grappled quite openly and vocally with this alienation. -

Ahead of Their Time

NUMBER 2 2013 Ahead of Their Time About this Issue In the modern era, it seems preposterous that jazz music was once National Council on the Arts Joan Shigekawa, Acting Chair considered controversial, that stream-of-consciousness was a questionable Miguel Campaneria literary technique, or that photography was initially dismissed as an art Bruce Carter Aaron Dworkin form. As tastes have evolved and cultural norms have broadened, surely JoAnn Falletta Lee Greenwood we’ve learned to recognize art—no matter how novel—when we see it. Deepa Gupta Paul W. Hodes Or have we? When the NEA first awarded grants for the creation of video Joan Israelite Maria Rosario Jackson games about art or as works of art, critical reaction was strong—why was Emil Kang the NEA supporting something that was entertainment, not art? Yet in the Charlotte Kessler María López De León past 50 years, the public has debated the legitimacy of street art, graphic David “Mas” Masumoto Irvin Mayfield, Jr. novels, hip-hop, and punk rock, all of which are now firmly established in Barbara Ernst Prey the cultural canon. For other, older mediums, such as television, it has Frank Price taken us years to recognize their true artistic potential. Ex-officio Sen. Tammy Baldwin (D-WI) In this issue of NEA Arts, we’ll talk to some of the pioneers of art Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) Rep. Betty McCollum (D-MN) forms that have struggled to find acceptance by the mainstream. We’ll Rep. Patrick J. Tiberi (R-OH) hear from Ian MacKaye, the father of Washington, DC’s early punk scene; Appointment by Congressional leadership of the remaining ex-officio Lady Pink, one of the first female graffiti artists to rise to prominence in members to the council is pending. -

It's Not a Fashion Statement

Gielis /1 MASTER THESIS NORTH AMERICAN STUDIES IT’S NOT A FASHION STATEMENT. AN EXPLORATION OF MASCULINITY AND FEMININITY IN CONTEMPORARY EMO MUSIC. Name of student: Claudia Gielis MA Thesis Advisor: Dr. M. Roza MA Thesis 2nd reader: Prof. Dr. F. Mehring Gielis /2 ENGELSE TAAL EN CULTUUR Teacher who will receive this document: Dr. M. Roza and Prof. Dr. F. Mehring Title of document: It’s Not a Fashion Statement. An exploration of Masculinity and Femininity in Contemporary Emo Music. Name of course: MA Thesis North American Studies Date of submission: 15 August 2018 The work submitted here is the sole responsibility of the undersigned, who has neither committed plagiarism nor colluded in its production. Signed Name of student: Claudia Gielis Gielis /3 Abstract Masculinity and femininity can be performed in many ways. The emo genre explores a variety of ways in which gender can be performed. Theories on gender, masculinity and femininity will be used to analyze both the lyrics and the music videos of these two bands, indicating how they perform gender lyrically and visually. Likewise a short introduction on emo music will be given, to gain a better understanding of the genre and the subculture. It will become clear that the emo subculture allows for men and women to explore their own identity. This is reflected in the music associated to the emo genre as well as their visual representation in their music videos. This essay will explore how both a male fronted band, My Chemical Romance, and a female fronted band, Paramore, perform gender. All studio albums and official music videos will be used to investigate how they have performed gender throughout their career. -

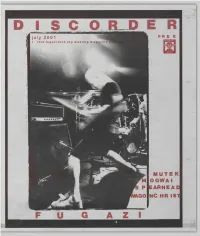

I S C O R D E R Free

I S C O R D E R FREE IUTE K OGWAI ARHEAD NC HR IS1 © "DiSCORDER" 2001 by the Student Radio Society of the University of British Columbia. All rights reserved. Circuldtion 1 7,500. Subscriptions, payable in advance, to Canadian residents are $15 for one year, to residents of the USA are $15 US; $24 CDN elsewhere. Single copies are $2 (to cover postage, of course). Please make cheques or money orders payable to DiSCORDER Mag azine. DEADLINES: Copy deadline for the August issue is July 14th. Ad space is available until July 21st and ccn be booked by calling Maren at 604.822.3017 ext. 3. Our rates are available upon request. DiS CORDER is not responsible for loss, damage, or any other injury to unsolicited mcnuscripts, unsolicit ed drtwork (including but not limited to drawings, photographs and transparencies), or any other unsolicited material. Material can be submitted on disc or in type. As always, English is preferred. Send e-mail to DSCORDER at [email protected]. From UBC to Langley and Squamish to Bellingham, CiTR can be heard at 101.9 fM as well as through all major cable systems in the Lower Mainland, except Shaw in White Rock. Call the CiTR DJ line at 822.2487, our office at 822.301 7 ext. 0, or our news and sports lines at 822.3017 ext. 2. Fax us at 822.9364, e-mail us at: [email protected], visit our web site at http://www.ams.ubc.ca/media/citr or just pick up a goddamn pen and write #233-6138 SUB Blvd., Vancouver, BC. -

Money, and Power by Shanti Webley

lll.llt: \C(. Sf(. I IIF [t.tP.£~~!" Marilyn Massey makes 10£1.1 f'lllo ~Ill ~.UI· Pitze( svery own R Revolution in · Sex, Money, Interview with F Welcome home' Volume XXVI February 1996 the other side Its confusing. And yet there doesn't seem to time for confusion volume xxvi these days. We've made some changes in this issue of the Other Side. It goes issue #1 without saying that last semester the magazine drew some criticism for its '1ess than objective" crusade against the administration. It's not that I editors-in-chief: feel guilty about that, or even at faull Last semester was a different time, aaron balkan ~~Fm·~~~ll"''r·""·those tmprecedented Pitzer days; where an Wlprecedented 85 degreetempera~· different feelings. I think there were a lot of us who felt compelled to try 11.1 for what seems like WeeiCS; when an Wlprecedented February snn ~ks over Mt. and change some things about Pitzer that we thought were wrong. And quinn burson at just the angle to cut through the smog to convene upon the glorious Inland Valley:.Empire at we weren't wrong for that; perhaps a bit foolish, but certainly not wrong. director of the media lab: F";)~~~: the'Jight spot: Pitzer's campus; not Pomona, not the Oaremont Colleges, but Pitzer. An tmprecedented Its funny, because in retrospect, I don't remember being convinced that matthew cooke thaf makes for unprecedented discussion. On one such day I was walking with a friend when here these "problems" were vealed to me, "If I were a perspective student and I came to Pitzer on a day like this. -

Cosmic Closet Lishments; for the Most Part, They Are Run by Very Nice People Who Are Trying to Give Club & Streetwear for Girls This Music an Outlet

' . Fugazi-Red Medicine "This CD is $8, postpaid." This quote can be found at the bot- boys from D.C. haven't lost the Fugazi ferocity, but it is a bit differ- tom of every one ofFugazi's last five releases, including their latest, ent. Red Medicine. Not much has changed for these messiahs of the in die The vocal tracks seem to be split about evenly between ex-Minor world. All their concerts are still five dollars, and they are still with Threat singer, Ian Mackaye, and Guy Picciotto. Mackaye sings on Dischord Records. Where most bands have managed to catapult "Back to Base," which is probably the most up-to-speed song on the themselves into the big money-making arena, Fugazi manages to album. He opens with ~ distinctive borderline yell, "Autonomy is a do just fine looking out from below. world of difference/ they're creeping around but they know they Red Medicine is undoubtedly Fugazi's most experimental al- can't-come in." bum to-date. But what about old Fugazi? I thought the same thing, The album is filled with a lot of moments with great musical but thinking about it, I realized that being diverse and reinventive value and then some. Highlights include, "Birthday Pony," the in- is a very good thing. Would you want to play the same· kind of.stuff strumental "Combination Lock" and the energetic "Downed City." over and over again? In the album opener, "Do you like me?" the Their tempo has slowed and their concentration on playing good intro sounds like someone is dropping his guitar, setting anticipa- music has intensified. -

The Clash and Mass Media Messages from the Only Band That Matters

THE CLASH AND MASS MEDIA MESSAGES FROM THE ONLY BAND THAT MATTERS Sean Xavier Ahern A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2012 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Kristen Rudisill © 2012 Sean Xavier Ahern All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor This thesis analyzes the music of the British punk rock band The Clash through the use of media imagery in popular music in an effort to inform listeners of contemporary news items. I propose to look at the punk rock band The Clash not solely as a first wave English punk rock band but rather as a “news-giving” group as presented during their interview on the Tom Snyder show in 1981. I argue that the band’s use of communication metaphors and imagery in their songs and album art helped to communicate with their audience in a way that their contemporaries were unable to. Broken down into four chapters, I look at each of the major releases by the band in chronological order as they progressed from a London punk band to a globally known popular rock act. Viewing The Clash as a “news giving” punk rock band that inundated their lyrics, music videos and live performances with communication images, The Clash used their position as a popular act to inform their audience, asking them to question their surroundings and “know your rights.” iv For Pat and Zach Ahern Go Easy, Step Lightly, Stay Free. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the help of many, many people. -

Dischord Records 3819 BEECHER ST

FUGAZi "First Demo" dischord rEcords DIS181 DIS181CD 11-song CD DIS181V 11-song LP+MP3 Release Date: November 18, 2014 Ian MacKaye - vocals, guitar Guy Picciotto - vocals Joe Lally - bass Brendan Canty - drums In early January 1988 and after only ten shows, Fugazi decided to go into Inner Ear Studio to see what their music sounded like on tape. Despite the fact that Ian, Joe, and Brendan had been playing together for nearly a year, it was still early days for the band. Guy had only been a full member of Fugazi for a few months and only sang lead on one song ("Break In"). It would be nearly another year before he would start playing guitar with the band. At that time, the studio was still located in the basement of engineer Don Zientara's family house. It was a familiar space as almost all of the members of Fugazi had recorded there with their previous bands (Teen Idles, Minor Threat, Deadline, Insurrection, Rites of Spring, Skewbald, Embrace, and One Last Wish). Joey Picuri (aka Joey P), who would later become one of Fugazi's longtime sound engineers, joined the band for the initial tracking. The sessions only lasted a couple of days, but tour dates and indecision about the tape would delay the final mix for another two months. Though the band was at first pleased with the results, it soon became clear that this tape would remain a demo as new songs were being written and the older songs were evolving and changing shape while the band was out on tour. -

Punk, Confrontation, and the Process of Validating Truth Claims

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 2011 Being in the Know: Punk, Confrontation, and the Process of Validating Truth Claims Christopher Richard Penna Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Penna, Christopher Richard, "Being in the Know: Punk, Confrontation, and the Process of Validating Truth Claims" (2011). Master's Theses. 525. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/525 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2011 Christopher Richard Penna LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO BEING IN THE KNOW: PUNK, CONFRONTATION, AND THE PROCESS OF VALIDATING TRUTH CLAIMS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS PROGRAM IN CULTURAL AND EDUCATIONAL POLICY STUDIES BY CHRISTOPHER R. PENNA DIRECTOR: NOAH W. SOBE, PH.D CHICAGO, IL AUGUST 2011 Copyright by Christopher R. Penna, 2011 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank all of the people who helped me a long this process of writing this thesis. I was blessed to have a line of outstanding professors in my program in Cultural Educational Policy Studies at Loyola University Chicago, but I want to thank in particular, Dr. Noah Sobe for advising me and encouraging me to believe that I am not crazy to write about punk.