Rill^ 1980S DC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson

The Interplay of Authority, Masculinity, and Signification in the “Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014, Holly Johnson ii Abstract This thesis will deconstruct the "grunge killed '80s metal” narrative, to reveal the idealization by certain critics and musicians of that which is deemed to be authentic, honest, and natural subculture. The central theme is an analysis of the conflicting masculinities of glam metal and grunge music, and how these gender roles are developed and reproduced. I will also demonstrate how, although the idealized authentic subculture is positioned in opposition to the mainstream, it does not in actuality exist outside of the system of commercialism. The problematic nature of this idealization will be examined with regard to the layers of complexity involved in popular rock music genre evolution, involving the inevitable progression from a subculture to the mainstream that occurred with both glam metal and grunge. I will illustrate the ways in which the process of signification functions within rock music to construct masculinities and within subcultures to negotiate authenticity. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my academic advisor Dr. William Echard for his continued patience with me during the thesis writing process and for his invaluable guidance. I also would like to send a big thank you to Dr. James Deaville, the head of Music and Culture program, who has given me much assistance along the way. -

Let's Say You're in a Band

Hello from Jenny Toomey & Kristin John Henderson’s CD tidbits were right on the money. In the fourth edition we Thomson and welcome to the 2000 added a bit of basic info on publishing, copyrighting, “going legal”. For this one digital version of the Mechanic’s we’ve updated some of the general info and included some URLs for some of Guide. Between 1990 and 1998 the companies that can help with CD or record production. we ran an indie record label called Simple Machines. Over One thing to keep in mind. This booklet is just a basic blueprint, and even though those eight years we we write about putting out records or CDs, a lot of this is common sense. We released about 75 records by know people who have used this kind of information to do everything from our own bands and those of putting out a 7” to starting an independent clothing label to opening recording our friends. We closed the studios, record stores, cafes, microbreweries, thrift stores, bookshops, and now whole operation down in thousands of start-up internet companies. Some friends have even used similar March, 1997. skills to organize political campaigns and rehabilitative vocational programs offering services to youth offenders in DC. Ironically, one of our label's most popular releases was There is nothing that you can’t do with a little time, creativity, enthusiasm and not a record, but a 24-page hard work. An independent business that is run with ingenuity, love and a sense "Introductory Mechanics of community can even be more important than the products and services it Guide to Putting out sells because an innovative business will, if successful, stretch established defini- Records”. -

Dag Nasty Wig out at Denkos Mp3, Flac, Wma

Dag Nasty Wig Out At Denkos mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Wig Out At Denkos Country: US Released: 1987 Style: Hardcore, Punk MP3 version RAR size: 1868 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1240 mb WMA version RAR size: 1751 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 350 Other Formats: AC3 MP3 MP4 MPC DMF AIFF AUD Tracklist A1 The Godfather A2 Trying A3 Safe A4 Fall A5 When I Move B1 Simple Minds B2 Wig Out At Denkos B3 Exercise B4 Dag Nasty B5 Crucial Three Companies, etc. Copyright (c) – Dischord Records Phonographic Copyright (p) – Dischord Records Produced At – Inner Ear Studios Recorded At – Inner Ear Studios Pressed By – MPO Credits Bass – Doug Carrion Drums – Colin Sears Engineer – Don Zientara Graphics – Cynthia Connolly Guitar – Brian Baker Photography By – Ken Salerno, Tomas Squip Producer – Don*, Ian* Songwriter – Dag Nasty Vocals – Peter Cortner Notes Includes black and white insert with lyrics one the one and a photo on the other side Produced at Inner Ear Studios. Recorded at Inner Ear Studios. This album is $5. postpaid from Dischord Records. c & p 1987 Dischord Records. Made in France. Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Runout A [etched]): DISCHORD 26 A-1 MPO Matrix / Runout (Runout B [etched]): DISCHORD 26 B-1 MPO Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Dag Wig Out At Denkos Dischord Dischord 26 Dischord 26 US 1987 Nasty (LP, Album) Records Wig Out At Denko's Dag Dischord DIS26CD (CD, Album, RE, DIS26CD US 2002 Nasty Records RM) Dischord Dischord 26, Dischord 26, Dag Wig Out At Denkos Records, Dischord Dischord US Unknown Nasty (LP, Album, RP) Dischord Records 26 Records 26 Records Dag Wig Out At Denkos Dischord Dischord 26 Dischord 26 UK 1987 Nasty (LP, Album, TP) Records Dischord Records, Wig Out At Denkos 26, dis26v, Dag Dischord 26, dis26v, (LP, Album, RM, US 2009 Dischord 26 Nasty Records, Dischord 26 RP) Dischord Records Related Music albums to Wig Out At Denkos by Dag Nasty 1. -

La Fugazi Live Series Sylvain David

Document generated on 10/01/2021 9:37 p.m. Sens public « Archive-it-yourself » La Fugazi Live Series Sylvain David (Re)constituer l’archive Article abstract 2016 Fugazi, one of the most respected bands of the American independent music scene, recently posted almost all of its live performances online, releasing over URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1044387ar 800 recordings made between 1987 and 2003. Such a project is atypical both by DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1044387ar its size, rock groups being usually content to produce one or two live albums during the scope of their career, and by its perspective, Dischord Records, an See table of contents independent label, thus undertaking curatorial activities usually supported by official cultural institutions such as museums, libraries and universities. This approach will be considered here both in terms of documentation, the infinite variations of the concerts contrasting with the arrested versions of the studio Publisher(s) albums, and of the musical canon, Fugazi obviously wishing, by the Département des littératures de langue française constitution of this digital archive, to contribute to a parallel rock history. ISSN 2104-3272 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article David, S. (2016). « Archive-it-yourself » : la Fugazi Live Series. Sens public. https://doi.org/10.7202/1044387ar Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) Sens-Public, 2016 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. -

Read Razorcake Issue #27 As A

t’s never been easy. On average, I put sixty to seventy hours a Yesterday, some of us had helped our friend Chris move, and before we week into Razorcake. Basically, our crew does something that’s moved his stereo, we played the Rhythm Chicken’s new 7”. In the paus- IInot supposed to happen. Our budget is tiny. We operate out of a es between furious Chicken overtures, a guy yelled, “Hooray!” We had small apartment with half of the front room and a bedroom converted adopted our battle call. into a full-time office. We all work our asses off. In the past ten years, That evening, a couple bottles of whiskey later, after great sets by I’ve learned how to fix computers, how to set up networks, how to trou- Giant Haystacks and the Abi Yoyos, after one of our crew projectile bleshoot software. Not because I want to, but because we don’t have the vomited with deft precision and another crewmember suffered a poten- money to hire anybody to do it for us. The stinky underbelly of DIY is tially broken collarbone, This Is My Fist! took to the six-inch stage at finding out that you’ve got to master mundane and difficult things when The Poison Apple in L.A. We yelled and danced so much that stiff peo- you least want to. ple with sourpusses on their faces slunk to the back. We incited under- Co-founder Sean Carswell and I went on a weeklong tour with our aged hipster dancing. -

Four Old Seven Inches on a Twelve Inch Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various Four Old Seven Inches On A Twelve Inch mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Four Old Seven Inches On A Twelve Inch Country: US Released: 2007 Style: Hardcore, Punk MP3 version RAR size: 1239 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1382 mb WMA version RAR size: 1928 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 752 Other Formats: AU MOD MP2 MP4 AAC APE VOX Tracklist A1 –The Teen Idles Teen Idles A2 –The Teen Idles Sneakers A3 –The Teen Idles Get Up And Go A4 –The Teen Idles Deadhead A5 –The Teen Idles Fleeting Fury A6 –The Teen Idles Fiorrucci Nightmare A7 –The Teen Idles Getting In My Way A8 –The Teen Idles Too Young To Rock A9 –State Of Alert Lost In Space A10 –State Of Alert Draw Blank A11 –State Of Alert Girl Problems A12 –State Of Alert Blackout A13 –State Of Alert Gate Crashers A14 –State Of Alert Warzone A15 –State Of Alert Riot A16 –State Of Alert Gang Fight A17 –State Of Alert Public Defender A18 –State Of Alert Gonna Have To Fight B1 –Government Issue Religious Ripoff B2 –Government Issue Fashionite B3 –Government Issue Rock & Roll Bullshit B4 –Government Issue Anarchy Is Dead B5 –Government Issue Sheer Terror B6 –Government Issue Asshole B7 –Government Issue Bored To Death B8 –Government Issue No Rights B9 –Government Issue I'm James Dean B10 –Government Issue Cowboy Fashion B11 –Youth Brigade It's About Time That We Had A Change B12 –Youth Brigade Full Speed Ahead B13 –Youth Brigade Point Of View B14 –Youth Brigade Barbed Wire B15 –Youth Brigade Pay No Attention B16 –Youth Brigade Wrong Decision B17 –Youth Brigade No Song B18 –Youth Brigade No Song II Companies, etc. -

Ahead of Their Time

NUMBER 2 2013 Ahead of Their Time About this Issue In the modern era, it seems preposterous that jazz music was once National Council on the Arts Joan Shigekawa, Acting Chair considered controversial, that stream-of-consciousness was a questionable Miguel Campaneria literary technique, or that photography was initially dismissed as an art Bruce Carter Aaron Dworkin form. As tastes have evolved and cultural norms have broadened, surely JoAnn Falletta Lee Greenwood we’ve learned to recognize art—no matter how novel—when we see it. Deepa Gupta Paul W. Hodes Or have we? When the NEA first awarded grants for the creation of video Joan Israelite Maria Rosario Jackson games about art or as works of art, critical reaction was strong—why was Emil Kang the NEA supporting something that was entertainment, not art? Yet in the Charlotte Kessler María López De León past 50 years, the public has debated the legitimacy of street art, graphic David “Mas” Masumoto Irvin Mayfield, Jr. novels, hip-hop, and punk rock, all of which are now firmly established in Barbara Ernst Prey the cultural canon. For other, older mediums, such as television, it has Frank Price taken us years to recognize their true artistic potential. Ex-officio Sen. Tammy Baldwin (D-WI) In this issue of NEA Arts, we’ll talk to some of the pioneers of art Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) Rep. Betty McCollum (D-MN) forms that have struggled to find acceptance by the mainstream. We’ll Rep. Patrick J. Tiberi (R-OH) hear from Ian MacKaye, the father of Washington, DC’s early punk scene; Appointment by Congressional leadership of the remaining ex-officio Lady Pink, one of the first female graffiti artists to rise to prominence in members to the council is pending. -

It's Not a Fashion Statement

Gielis /1 MASTER THESIS NORTH AMERICAN STUDIES IT’S NOT A FASHION STATEMENT. AN EXPLORATION OF MASCULINITY AND FEMININITY IN CONTEMPORARY EMO MUSIC. Name of student: Claudia Gielis MA Thesis Advisor: Dr. M. Roza MA Thesis 2nd reader: Prof. Dr. F. Mehring Gielis /2 ENGELSE TAAL EN CULTUUR Teacher who will receive this document: Dr. M. Roza and Prof. Dr. F. Mehring Title of document: It’s Not a Fashion Statement. An exploration of Masculinity and Femininity in Contemporary Emo Music. Name of course: MA Thesis North American Studies Date of submission: 15 August 2018 The work submitted here is the sole responsibility of the undersigned, who has neither committed plagiarism nor colluded in its production. Signed Name of student: Claudia Gielis Gielis /3 Abstract Masculinity and femininity can be performed in many ways. The emo genre explores a variety of ways in which gender can be performed. Theories on gender, masculinity and femininity will be used to analyze both the lyrics and the music videos of these two bands, indicating how they perform gender lyrically and visually. Likewise a short introduction on emo music will be given, to gain a better understanding of the genre and the subculture. It will become clear that the emo subculture allows for men and women to explore their own identity. This is reflected in the music associated to the emo genre as well as their visual representation in their music videos. This essay will explore how both a male fronted band, My Chemical Romance, and a female fronted band, Paramore, perform gender. All studio albums and official music videos will be used to investigate how they have performed gender throughout their career. -

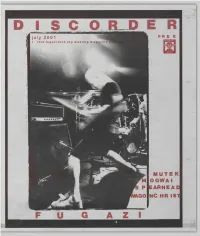

I S C O R D E R Free

I S C O R D E R FREE IUTE K OGWAI ARHEAD NC HR IS1 © "DiSCORDER" 2001 by the Student Radio Society of the University of British Columbia. All rights reserved. Circuldtion 1 7,500. Subscriptions, payable in advance, to Canadian residents are $15 for one year, to residents of the USA are $15 US; $24 CDN elsewhere. Single copies are $2 (to cover postage, of course). Please make cheques or money orders payable to DiSCORDER Mag azine. DEADLINES: Copy deadline for the August issue is July 14th. Ad space is available until July 21st and ccn be booked by calling Maren at 604.822.3017 ext. 3. Our rates are available upon request. DiS CORDER is not responsible for loss, damage, or any other injury to unsolicited mcnuscripts, unsolicit ed drtwork (including but not limited to drawings, photographs and transparencies), or any other unsolicited material. Material can be submitted on disc or in type. As always, English is preferred. Send e-mail to DSCORDER at [email protected]. From UBC to Langley and Squamish to Bellingham, CiTR can be heard at 101.9 fM as well as through all major cable systems in the Lower Mainland, except Shaw in White Rock. Call the CiTR DJ line at 822.2487, our office at 822.301 7 ext. 0, or our news and sports lines at 822.3017 ext. 2. Fax us at 822.9364, e-mail us at: [email protected], visit our web site at http://www.ams.ubc.ca/media/citr or just pick up a goddamn pen and write #233-6138 SUB Blvd., Vancouver, BC. -

Cosmic Closet Lishments; for the Most Part, They Are Run by Very Nice People Who Are Trying to Give Club & Streetwear for Girls This Music an Outlet

' . Fugazi-Red Medicine "This CD is $8, postpaid." This quote can be found at the bot- boys from D.C. haven't lost the Fugazi ferocity, but it is a bit differ- tom of every one ofFugazi's last five releases, including their latest, ent. Red Medicine. Not much has changed for these messiahs of the in die The vocal tracks seem to be split about evenly between ex-Minor world. All their concerts are still five dollars, and they are still with Threat singer, Ian Mackaye, and Guy Picciotto. Mackaye sings on Dischord Records. Where most bands have managed to catapult "Back to Base," which is probably the most up-to-speed song on the themselves into the big money-making arena, Fugazi manages to album. He opens with ~ distinctive borderline yell, "Autonomy is a do just fine looking out from below. world of difference/ they're creeping around but they know they Red Medicine is undoubtedly Fugazi's most experimental al- can't-come in." bum to-date. But what about old Fugazi? I thought the same thing, The album is filled with a lot of moments with great musical but thinking about it, I realized that being diverse and reinventive value and then some. Highlights include, "Birthday Pony," the in- is a very good thing. Would you want to play the same· kind of.stuff strumental "Combination Lock" and the energetic "Downed City." over and over again? In the album opener, "Do you like me?" the Their tempo has slowed and their concentration on playing good intro sounds like someone is dropping his guitar, setting anticipa- music has intensified. -

“Punk Rock Is My Religion”

“Punk Rock Is My Religion” An Exploration of Straight Edge punk as a Surrogate of Religion. Francis Elizabeth Stewart 1622049 Submitted in fulfilment of the doctoral dissertation requirements of the School of Language, Culture and Religion at the University of Stirling. 2011 Supervisors: Dr Andrew Hass Dr Alison Jasper 1 Acknowledgements A debt of acknowledgement is owned to a number of individuals and companies within both of the two fields of study – academia and the hardcore punk and Straight Edge scenes. Supervisory acknowledgement: Dr Andrew Hass, Dr Alison Jasper. In addition staff and others who read chapters, pieces of work and papers, and commented, discussed or made suggestions: Dr Timothy Fitzgerald, Dr Michael Marten, Dr Ward Blanton and Dr Janet Wordley. Financial acknowledgement: Dr William Marshall and the SLCR, The Panacea Society, AHRC, BSA and SOCREL. J & C Wordley, I & K Stewart, J & E Stewart. Research acknowledgement: Emily Buningham @ ‘England’s Dreaming’ archive, Liverpool John Moore University. Philip Leach @ Media archive for central England. AHRC funded ‘Using Moving Archives in Academic Research’ course 2008 – 2009. The 924 Gilman Street Project in Berkeley CA. Interview acknowledgement: Lauren Stewart, Chloe Erdmann, Nathan Cohen, Shane Becker, Philip Johnston, Alan Stewart, N8xxx, and xEricx for all your help in finding willing participants and arranging interviews. A huge acknowledgement of gratitude to all who took part in interviews, giving of their time, ideas and self so willingly, it will not be forgotten. Acknowledgement and thanks are also given to Judy and Loanne for their welcome in a new country, providing me with a home and showing me around the Bay Area. -

Norway's Jazz Identity by © 2019 Ashley Hirt MA

Mountain Sound: Norway’s Jazz Identity By © 2019 Ashley Hirt M.A., University of Idaho, 2011 B.A., Pittsburg State University, 2009 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Musicology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Musicology. __________________________ Chair: Dr. Roberta Freund Schwartz __________________________ Dr. Bryan Haaheim __________________________ Dr. Paul Laird __________________________ Dr. Sherrie Tucker __________________________ Dr. Ketty Wong-Cruz The dissertation committee for Ashley Hirt certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: _____________________________ Chair: Date approved: ii Abstract Jazz musicians in Norway have cultivated a distinctive sound, driven by timbral markers and visual album aesthetics that are associated with the cold mountain valleys and fjords of their home country. This jazz dialect was developed in the decade following the Nazi occupation of Norway, when Norwegians utilized jazz as a subtle tool of resistance to Nazi cultural policies. This dialect was further enriched through the Scandinavian residencies of African American free jazz pioneers Don Cherry, Ornette Coleman, and George Russell, who tutored Norwegian saxophonist Jan Garbarek. Garbarek is credited with codifying the “Nordic sound” in the 1960s and ‘70s through his improvisations on numerous albums released on the ECM label. Throughout this document I will define, describe, and contextualize this sound concept. Today, the Nordic sound is embraced by Norwegian musicians and cultural institutions alike, and has come to form a significant component of modern Norwegian artistic identity. This document explores these dynamics and how they all contribute to a Norwegian jazz scene that continues to grow and flourish, expressing this jazz identity in a world marked by increasing globalization.