Cognitive Technologies for Writing Roy D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring Users' Perceptions and Expectations of Security

Cloudy with a Chance of Misconceptions: Exploring Users’ Perceptions and Expectations of Security and Privacy in Cloud Office Suites Dominik Wermke, Nicolas Huaman, Christian Stransky, Niklas Busch, Yasemin Acar, and Sascha Fahl, Leibniz University Hannover https://www.usenix.org/conference/soups2020/presentation/wermke This paper is included in the Proceedings of the Sixteenth Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security. August 10–11, 2020 978-1-939133-16-8 Open access to the Proceedings of the Sixteenth Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security is sponsored by USENIX. Cloudy with a Chance of Misconceptions: Exploring Users’ Perceptions and Expectations of Security and Privacy in Cloud Office Suites Dominik Wermke Nicolas Huaman Christian Stransky Leibniz University Hannover Leibniz University Hannover Leibniz University Hannover Niklas Busch Yasemin Acar Sascha Fahl Leibniz University Hannover Leibniz University Hannover Leibniz University Hannover Abstract respective systems. These dedicated office tools helped the Cloud Office suites such as Google Docs or Microsoft Office adoption of personal computers over more dedicated or me- 365 are widely used and introduce security and privacy risks chanical systems for word processing. In recent years, another to documents and sensitive user information. Users may not major shift is happening in the world of office applications. know how, where and by whom their documents are accessible With Microsoft Office 365, Google Drive, and projects like and stored, and it is currently unclear how they understand and LibreOffice Online, most major office suites have moved to mitigate risks. We conduct surveys with 200 cloud office users provide some sort of cloud platform that allows for collabo- from the U.S. -

The Origins of Word Processing and Office Automation

Remembering the Office of the Future: The Origins of Word Processing and Office Automation Thomas Haigh University of Wisconsin Word processing entered the American office in 1970 as an idea about reorganizing typists, but its meaning soon shifted to describe computerized text editing. The designers of word processing systems combined existing technologies to exploit the falling costs of interactive computing, creating a new business quite separate from the emerging world of the personal computer. Most people first experienced word processing using a word processor, we think of a software as an application of the personal computer. package, such as Microsoft Word. However, in During the 1980s, word processing rivaled and the early 1970s, when the idea of word process- eventually overtook spreadsheet creation as the ing first gained prominence, it referred to a new most widespread business application for per- way of organizing work: an ideal of centralizing sonal computers.1 By the end of that decade, the typing and transcription in the hands of spe- typewriter had been banished to the corner of cialists equipped with technologies such as auto- most offices, used only to fill out forms and matic typewriters. The word processing concept address envelopes. By the early 1990s, high-qual- was promoted by IBM to present its typewriter ity printers and powerful personal computers and dictating machine division as a comple- were a fixture in middle-class American house- ment to its “data processing” business. Within holds. Email, which emerged as another key the word processing center, automatic typewriters application for personal computers with the and dictating machines were rechristened word spread of the Internet in the mid-1990s, essen- processing machines, to be operated by word tially extended word processing technology to processing operators rather than secretaries or electronic message transmission. -

Published In: Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science, Vol. 49 (New York: Dekker, 1992), Pp

Published in: Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science, vol. 49 (New York: Dekker, 1992), pp. 268-78 Author’s address: [email protected] WORD PROCESSING (HISTORY OF). Definition. The term and concept of “word processing” are by now so widely used that most readers will be already familiar with them. The term, created on the model of “data processing,” is more vague than commonly believed. A human editor, for example, obviously pro- cesses words, but is not what is meant by a “word proces- sor.” A number of software programs process words in one way or another--a concordance or indexing program, for example--but are not understood to be word processing programs.’ The term “word processor” means a facility that records keystrokes from a typewriter-like keyboard, and prints the output onto paper in a separate operation. In the meantime the data is stored, usually in memory or mag- netic media. A word processor also can make improve- ments in the stream of words before they are printed. At their most basic these include the ability to arrange words into lines. An “editor,” such as the infamous EDLINE distributed with the Microsoft Disk Operating System (MS-DOS), lacks the ability to structure lines. Commonly a word processor is understood to be a software program, and in the 1980s and 1990s it usually meant a program written for a microcomputer. However, preceding this period and continuing through it there have been hardware word processors. These are pieces of equip- ment sold for the sole purpose of word processing, con- taining in one package a keyboard, printer, recording and playback device, and in all recent examples a video or liquid crystal display screen. -

Instructions to the Students: Outlines: Understanding Word Processing Program

Karary University – Dr. Abdeldime Mohamed Salih – Lecture Note College of Medicine Lecture Two Title: Dealing With Word Processing Programs Instructions to the Students: By the end of this lecture readers will be familiar with Microsoft word usages. Before start: You need to use your own computer to practice the following skills The following note is prepared to understanding how to deal with the computer in general. Further information can be found at the reference given in the content of the subject. Also you can find more information in the internet. The content is prepared in such way that suits the pharmacy college students to help them dealing with Microsoft word. Also you contact the instructor in his office any time between 12:00 to 2:00 Word processing programs are constantly evolving. Try to keep as up-to-date as possible by reading computer-related news, blogs, RSS feeds, newsletters, forums, and following computer people on social networking sites. Micrsoft word is a very good tool for word processing and editing documents and has many properties that would help and you need to practice, practice, and practice! Outlines: 1. Understanding word processing Program 2. Word Processing Programs 3. Microsoft word 4. Some tips for saving time when using Microsoft word 5. Some exercises Understanding word processing Program In the past, the word processor was a device that provides for formatting and output of text, often with some additional features. Early word processors were stand-alone devices dedicated to this function, but current word processors are word processor programs running on general purpose computers to input, editing, formatting text. -

A History of the Personal Computer Index/11

A History of the Personal Computer 6100 CPU. See Intersil Index 6501 and 6502 microprocessor. See MOS Legend: Chap.#/Page# of Chap. 6502 BASIC. See Microsoft/Prog. Languages -- Numerals -- 7000 copier. See Xerox/Misc. 3 E-Z Pieces software, 13/20 8000 microprocessors. See 3-Plus-1 software. See Intel/Microprocessors Commodore 8010 “Star” Information 3Com Corporation, 12/15, System. See Xerox/Comp. 12/27, 16/17, 17/18, 17/20 8080 and 8086 BASIC. See 3M company, 17/5, 17/22 Microsoft/Prog. Languages 3P+S board. See Processor 8514/A standard, 20/6 Technology 9700 laser printing system. 4K BASIC. See Microsoft/Prog. See Xerox/Misc. Languages 16032 and 32032 micro/p. See 4th Dimension. See ACI National Semiconductor 8/16 magazine, 18/5 65802 and 65816 micro/p. See 8/16-Central, 18/5 Western Design Center 8K BASIC. See Microsoft/Prog. 68000 series of micro/p. See Languages Motorola 20SC hard drive. See Apple 80000 series of micro/p. See Computer/Accessories Intel/Microprocessors 64 computer. See Commodore 88000 micro/p. See Motorola 80 Microcomputing magazine, 18/4 --A-- 80-103A modem. See Hayes A Programming lang. See APL 86-DOS. See Seattle Computer A+ magazine, 18/5 128EX/2 computer. See Video A.P.P.L.E. (Apple Pugetsound Technology Program Library Exchange) 386i personal computer. See user group, 18/4, 19/17 Sun Microsystems Call-A.P.P.L.E. magazine, 432 microprocessor. See 18/4 Intel/Microprocessors A2-Central newsletter, 18/5 603/4 Electronic Multiplier. Abacus magazine, 18/8 See IBM/Computer (mainframe) ABC (Atanasoff-Berry 660 computer. -

UTILITIES PRINT Mp 1117 17511Y~R1 T SERIAI MT N IT,11

11 48784 $2.50 U.S. $2.95 CANADA FEBRUARY 1 ?88 THE MAGAZINE FOR THE ELECTRONICS ACTIVIST! The _ )0. Power Play ON ! Two power supplies in one 410 OFF NE ; case with digital readout G for voltage or current. SIDEC um.- NI PIS1110 ERI 11.11 UI/. 711KIS2 PIP :Ia 11 U.rr Isles (OPIMI (On 25717 2101111 1,1t.. INt PICT SPL I I/N/ MII71 kort .,Ad EDITOR p1 177721 11151111101 1.lrt tOt1 L«l;l lit NERI MI 7175 Atli SPL 7772 LONG AL? 191577 A. UTILITIES PRINT mP 1117 17511y~r1 t SERIAI MT N IT,11. bytes ..r1 Put your home computer SPELL Vol 22172 455768 19t.. fetal STARVI I17 112 TIOVE-1 11 IIIIS ...Niel 1. ... 1 .K/TREE YEK 725152 11 3M TIMIIIY011 Ldlri1 in We cover . LETTERS overdrive! POI /PIOC 11.,1.1 - 0111 041 22711 ÈUQIOIE REPLIES 1:16.. GOV.. ACTION the most powerful PERSONAL Ente cow I TYP. I C... =PMdEwa MI ht. I T. - SHIERS ,r packages available. - C rat 110. C. - OUI, Auno - 11(0115 Plus - INDUCTANCE BRIDGE 11.1 V1[ Unknown Ls to Henrys (..1_.u1..I01l.I lrt 1.. Set 11J V1. S..<1.1 Prut fete 0.01 T1 .r.M..l Doi On /rot. (.M ti01 it Prr..ltuY.N lee .. IF". WIND WITCHER .r <t1. <.y.l4l. pot. Tl.. 0.01 1..1yI.M 1!... ..I.tN .1t1 t011 ..1 011ry ,01 r1 .<1.,t .Y 1r 01 11 It tinkles without motion Ir (.L. 2747,1,11 15,27113,01 27,/Y21M4 274141,1 27,71444 DISH POSITIONER 27045,144 2704(711,1 1111 r TVRO remote move -it plans w.1I.,r4 .r. -

Newword — the Other Wordprocessor∗

Newword — the other wordprocessor∗ John R Hudson No, not the B word, nor even the T word, but Newword, the second wordprocessor after Tasword to appear for the CPC, albeit only the 128K machines. Newword was written by the authors of WordStar after they fell out with the company over the future direction of WordStar. WordStar was the second microcomputer wordprocessor — the Electric Pencil was the first — and, by the time I came across WordStar in 1980, it was being compared favourably with leading minicomputer wordprocessors. These were largely used in typing pools where an IBM golfball typewriter was considered state of the art. So WordStar was written with such typists in mind as well as the limitations of early microcomputer keyboards — just a typewriter keyboard plus control, escape and line feed. I used WordStar for over six years on an RML 380Z with two 8” double-sided disc drives — each side being treated as a separate 128K drive. WordStar overcame the memory and disc drive limitations of the early microcomputers in several ways. It only loaded the core functions into RAM, calling the remaining ones from disc as needed, and, as soon as a document became too long to be held in RAM, it used a technique now called ‘virtual RAM’, saving parts of the file to disc. You could alternate saves between drives, which made it appear I was using a 256K drive, and you could chain long documents across discs. In an attempt to break away from the limitations of classic WordStar on PCs, the company launched WordStar 2000 which sank almost without trace but caused the original authors to leave and produce Newword. -

Chapter 7 Cognitive Technologies for Writing

In E.Z Rothkopf (~d.) Review of Research in Education 14, 1987. Washington, D.C.: AERA, 1987., pp. 277-327. Chapter 7 Cognitive Technologies for Writing ROY D. PEA New York University Laboratory for Advanced Research in Educational Technologies and D. MlDlAN KURLAND Bank Street College Media Group Ludwig Wittgenstein: It is only the attempt to write down your ideas that enables them to develop (Drury, 1982). INTRODUCTION Current technologies are useful for improving the productivity and appear- ance of writing. However, with several notable exceptions, they neither offer qualitative advances over previous tools in helping mature writers express or refine their thoughts, nor help novices develop better writing skills. We pro- pose that writing tools contribute indirectly to writing development (e.g., by encouraging more writing) when they should provide direct support, in ways to be described. At the same time, an exciting new cognitive-developmental perspective on Support for writing an earlier draft of this chapter was provided by a grant from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation (No. B1983-25). We wish to thank the participants of the September 21- 23. 1983, workshop at Bank Street College, entitled Applying Cognitive Science to Cognitive Technologiesfor Writing Development. for provocative discussion of these issues, and for of- fering their experience and insights on the topics we highlight. The manuscript was revised and updated through March 1986. We are especially grateful to Carl Bereiter. Robert Bracewell, Bertram Bruce. Jerome Bruner. Kenneth Burke, Cynthia Char. Peter Elbow, Linda Flower. Lawrence Frase. Carl Frederiksen. Howard Gardner, Jan Hawkins. John Hayes. David Kaufer, James Levin. -

Electric Pencil Ii Operator's ~Nual Page 1

THe EL ECT R't C' PENC I LIt.. WORD PROCESSOR OPERATOR'S MANUA' Copyright ('C) 1977, 1978 MichaeL Sbrayer.- .. ALL Rights Reserved. The contents of this pubLication may not be reproduced in any form or by any means in whoLe orin part without the prior written cons'entof the copyright owner. ' MI CH A EL S HR AYE R S0 F'N. A RE 3901 Los'Feliz Boulev~~~ Los Angeles, CA 900~7 :::2..1 J - G(,l;" - /7s-r; TABLE OF CONTENTS Background •••••••••• ••••••• 1 Introduction •••••••• • ••••••••• 2 System Hardware Requirements •••••••• 3 Using This ManuaL •••••• ••• 3 GLossary ••••••••••••••••• 4 Getting Started ••••• 8. Commands and Functions ••••• 9 Cursor Motion Commands 10 ScroLLing and DispLay ControL •• 11 . DeLete and Insert •••••••• . .', 12 BLock Movement •••• 13 LF, FF, TAB and RETURN •••• 13 String Search ••••• •• 14 Search and RepLace ••••••••• 14 Coded String Searches •• 15 Repeat Function ••••• 15 Disk Sub-System Command TabLe •• 16 Word Number, Record Number 16 Disk Directory 17 Save Disk FiLe 18 KilL Disk File 18 Load Di sk File 19 Important Note II 19 Tape Reader ••••••••••• 20 Tape Writer •••• ••• 20 Tape Verify •••••••• 21 CLearing Commands •••••••••••• 21 Print Sub-System Command TabLe 22 . Dynamic Print Formatting •••••••••• 23 Text Commenting •••••••• 23 Print VaLue Definitions ••••• 24 Centering, UnderLining and BoLdface. 26 MuLti coLumn Printing •••••• 27 TitLing Pages and Page Numbering •••• 27 Printing with a DiabLo •••••••••• 28 Printing with a\TTY, SeLectric, etc. 28 Ex i t System •.• •••••••• 28 Loading The ELectric PenciL. 28 Registration •••••••• 29 THE ELECTRIC PENCIL II OPERATOR'S ~NUAL PAGE 1 BACKGROUND The Electric Pencil is a Character Oriented Word Processing System. -

List of Word Processors

List of word processors The following is a list of word processors. Entries should • IA Writer - Mac, iOS have a Wikipedia article or a citation to show notability. • Ichitaro - a Japanese word processor produced by JustSystems 1 Free and open-source software • InCopy • AbiWord • IntelliTalk • Apache OpenOffice Writer • iStudio Publisher - Mac • Calligra Words • Kingsoft Writer - Windows and Linux • EtherPad, real time word processor • Lotus Word Pro - Windows • GNU TeXmacs • Mariner Write - Mac • Groff • Mathematica - technical and scientific word process- • JWPce is a Japanese word processor, designed pri- ing marily for the English speaker who is reading or writing in Japanese. • Mellel - Mac • KWord • Microsoft Word - Windows and Mac • LyX • Microsoft Works Word Processor • LibreOffice Writer • Microsoft Write - Windows and Mac (a stripped- • Ted down version of Word) • Polaris Office • Nisus Writer - Mac • Nota Bene - Windows 2 Proprietary software • Polaris Office - Android and Windows Mobile 2.1 Commercial • PolyEdit • Adobe PageMaker • QuickOffice - Android, iOS, Symbian • Apple Pages, part of its iWork suite - Mac • Scrivener • Applix Word - Linux • TechWriter - RISC OS • Atlantis Word Processor - Windows • TextMaker • Documents To Go - Android, iOS, Windows Mo- bile, Symbian • ThinkFree Office Write • Final Draft Screenplay/Teleplay word processor • WordPad, previously known as “Write” in older ver- sions than Windows 95, has been included in all ver- • FrameMaker sions of Windows since Windows 1.01. Source code • Gobe Productive Word Processor -

Computer Connections

Dear This is the numbered limited distribution manuscript that I have ___,__ produced for my new book entitled Computer Connections. _As_a---_, manuscript, it contains numerous errors although I've t-r-ied to reduce them to a minimum. I have provided you with this for your perusal, and would appre ciate any comments if you run across errors. This is the "Christmas, 1993 Edition" that will go to print in final form early next year, apparently under the auspices of Osborne McGraw Hill. Please do not make copies or pass this edition along to anyone else other than your immediate family and associates. Thanks, and Merry Christmas, Gary Kildall Computer Connections People, Places, and Events in the Evolution of the Personal Computer Industry Gary Kildall Copyright (c) 1993, 1994 All Rights Reserved Prometheus Light and Sound 3959 Westlake Drive Austin, Texas, 78746 To My Friends and Business Associates Please Respect That This Manuscript is Confidential and Proprietary And Do Not Make Any Copies Ownership is by Prometheus Light and Sound and Gary Kildall as an Individual The Sole Purpose of Releasing this Manuscript for Review is to Provide a Basis For Producing a Commercially Publishable Book Copyright (c) 1993, 1994 Prometheus Light and Sound, Incorporated Any Corrections or Comments are Greatly Appreciated CHAPTER 1 One Person '.s Need For a Personal Computer 9 Kildall's Nautical School 9 CHAPTER 2 Seattle and the University of Washington 13 Computer Life at the "U-Dub" 13 ABlunder 14 Transition to Computers 15 Getting into Compilers -

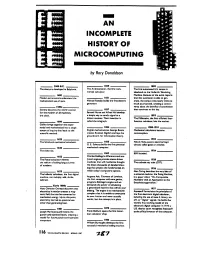

An Incomplete History of Microcomputing

l - - - - - w ' w ' ww - - - - AN - a- 5 =- - - INCOMPLETE ^ v ^ - - i HISTORY OF - - vv a cars MICROCOMPUTING ^ r v wssw v s F - by Rory Donaldson 3000 B.C. 1820 1890 The abacus is developed in Babylonia. The Arithmometer, the first com- The first automated U.S. census is mercial calculator. tabulated on the Hollerith Tabulating 1400 Machine. Because of the extra reports Moslem astronomers understand the 1831 that this automaton is able to gen- mathematical use of zero. Michael Faraday builds the first electric erate, the census costs nearly twice as generator. much as projected, creating a contro- I SOOs versy about the benefits of automation Geneva becomes the world's center 1837 that continues to this day. for the mother of all machines, Samuel Morse and Alfred Vail develop the clock. a simple way to send a signal to a 1893 distant receiver. Their invention is The Millionaire, the first efficient four- 1600 called the telegraph. function calculator, hits the market. Galileo brings together the exper- iential and mathematical into a single 1854 1900-1910 stream of inquiry that leads to the English mathematician George Boole Mechanical calculators become scientific method. creates Boolean Algebra and lays the commonplace. groundwork for information theory. 1623 1903 The Schickard mechanical calculator. 1855 _ Nikola Tesa patents electrical logic G. E. Scheutz builds the first practical circuits called gao or switches. 1630 mechanical computer. The slide rule. 1924 1862 _ IBM founded. 1652 Charles Babbage's difference and ana- The Pascal calculator relieves lytical engines promise steam-driven 1921 the tedium of adding long columns machines that will mechanize thought.