Mag.Net Reader: Experiences in Electronic Cultural Publishing (Forthcoming) Images

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

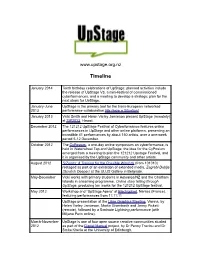

Upstage Timeline

www.upstage.org.nz Timeline January 2014 Tenth birthday celebrations of UpStage: planned activities include the release of UpStage V3, a mini-festival of commissioned cyberformances, and a meeting to develop a strategic plan for the next steps for UpStage. January-June UpStage is the primary tool for the trans-European networked 2013 performance collaboration We Have a Situation! January 2013 Vicki Smith and Helen Varley Jamieson present UpStage (remotely) at TIP2013, Hawaii. December 2012 The 121212 UpStage Festival of Cyberformance features online performances in UpStage and other online platforms, presenting an incredible 41 performances by about 150 artists, over a one-week period 5-12 December. October 2012 The CyPosium, a one-day online symposium on cyberformance, is held in Waterwheel Tap and UpStage; the idea for the CyPosium emerged from a meeting to plan the 121212 Upstage Festival, and it is organised by the UpStage community and other artists. August 2012 S/Zports: A Training for the Possible Wor(l)ds (from 101010) restaged as part of an exhibition of extended media, Zagrebi Dublje (Scratch Deeper) at the ULUS Gallery in Belgrade. May-December Vicki works with primary students in Aotearoa/NZ and the Chatham Islands in a learning programme, Online story telling through UpStage, producing ten works for the 121212 UpStage festival. May 2012 Workshop and “UpStage Apero” at Electropixel, Nantes (France), featuring performances from 11:11:11 UpStage presentation at the Libre Graphics Meeting, Vienna, by Helen Varley Jamieson, Martin Eisenbarth and Jenny Pickett (remote), followed by a 5-minute Lightning performance (with Miljana Peric online). -

Joana Chicau Is a Graphic Designer, Coder, Researcher

Joana Chicau is a designer and researcher — with a background in dance. She researches the intersection of the body with the designed and programmed environment, aiming at widening the ways in which digital sciences is presented and made accessible to the public. The latter informs a practice and exploration of various forms and formats — interweaving web programming with choreography — from the making of online platforms to performances and workshops. In parallel she has been participating and co-organizing events involving multi-location collaborative coding, algorithmic improvisation, open discussions on digital equity and activism. News & updates: www.joanachicau.com CURRENTLY Associate lecturer at Bsc and MA Internet Equalities at UAL Creative Computing Institute; Associate lecturer at Graphic and Media Design at London College of Communication; Member of Varia — Center for Everyday Technology; Co-founder of Netherlands Coding Live a series of live coding sessions, discussion and more; CROSS FIELD COMPETENCIES Knowledge in both research driven and practical assignments for both both industry and cultural spheres; Professional with a variety of analogue and digital tools as well as work environments; Record in concept development and design production; with projects requiring diverse design thinking strategies across mediums; experienced and enthusiastic about collaborative and creative workflows; having used diverse methodologies from mood boards and ideation maps; role playing games; design sprints to scrums, acquainted with coding dojo; as well programming iterations, such as agile mob. Organizational skills, such as developing timelines and devising plans. Practice in producing tutorials for usage of online platforms and documentation of code (HTML; CSS; JS); Performed applied research on web and interface accessibility and techniques for handling assistive technology. -

Download It Here

Time to Show and Tell Neal Stephenson likens operating systems to cars. In his analogy, Windows is a station wagon and Mac OS is an expensive, attractive European-style car. The two are available in dealerships, along with all the normal service options. Linux, on the other hand, is a tank. Not only a tank, but a free one. It's a stronger, faster, more reliable vehicle with a personal approach to maintenance. But it doesn't have a dealership or ad budget. Libre Graphics is in a similar situation. It's strong, fast, reliable and even diverse. It has great community support and investment. And like Stephenson's tanks, it's being cranked out and offered to anyone who will take it. Both the Libre Graphics Meeting and this magazine exist to serve the Libre Graphics community. LGM, now in its fifth year, has been a venue for developers to meet, organize and work. In this magazine, we present to you the output of that work. Libre Graphics #0 showcases the work of developers, users, artists and people with any number of other titles. Some do performance art, some make films. In common, they have Libre Graphics. Why make new fonts? Dave Crossland (www.understandingfonts.com) "Why make new fonts?" is the most common question I have been asked since I set out to become a typeface designer. When I mention I did a Masters degree in the subject, at the University of Reading, England, I sometimes meet genuine surprise that this subject is studied seriously. Often, people haven't ever thought about where fonts come from, since the fonts on their computer are just there, you know? We see different fonts out in the world constantly, so we all know there sure are a lot of them. -

La Construcción De La Narrativa En Los Laboratorios Ciudadanos. El Caso De Medialab-Prado

UNIVESIDAD NACIONAL DE EDUCACIÓN A DISTANCIA MÁSTER EN COMUNICACIÓN Y EDUCACIÓN EN LA RED FACULTAD DE EDUCACIÓN Departamento de Didáctica, Organización Escolar y Didácticas Especiales Trabajo Fin de Máster, Subprograma Comunicación y Educación en la Red Título: La Construcción de la Narrativa en los Laboratorios Ciudadanos. El caso de Medialab-Prado Presentado por María Erica Parrado Roldán Bajo la dirección de María Del Carmen Navarro García – Suelto Convocatoria Junio 2018-2019 3 Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución 4.0 Internacional Usted es libre de: Compartir: Copiar y redistribuir el material en cualquier medio o formato. Adaptar: Mezclar, transformar y construir, partiendo de este material, para cualquier propósito, incluso comercial. La licenciante no puede revocar estas libertades en tanto usted siga los términos de la licencia. 4 Agradecimientos En el camino andado a lo largo de todos estos años de estudio, me he encontrado con personas maravillosas que han hecho posible este trabajo. Quiero agradecer: A Medialab-Prado, a todos sus trabajadores y colaboradores, puesto que durante mi estancia en el centro ha sido una segunda casa para mí. Me llevo una grata experiencia, donde he conocido a muchas personas, que me han aportado otra visión del mundo. Por acogerme y contarme vuestra magnífica labor en Medialab-Prado: gracias a todas las personas que me han concedido una entrevista: Fran, profesores de Art Skill y alumnos, Sara, Vanesa, Pablo, Gerardo, Rubén, Gonzalo, Julián, Lorena, Daniel, Javier B., Fabi y Joaku, María y Miguel, Clara, Patricia, Bordignon, Margarita, Javier L., y Lola. Gracias a Julio, mi primer contacto en Medialab, por toda la información ofrecida. -

Advisory Council Appointments Reappointments

ECC Board of Trustees Executive Summary Date: February 23, 2017 Subcommittee: Curriculum and Student Success Agenda Item: Advisory Council Appointments or Reappointments to the Architecture Technology AAS Degree Program; Dental Laboratory Technology AAS Degree Program; Hospitality Management AAS, AOS and Certificate Programs; Information Technology AAS Degree Program; and Visual Communication Technology AAS Degree Program This item is for: For Board's Approval Backup Documentation: Attached to this document Background Information: The appointments or reappointments of Advisory Council members is requested by (resumes follow in alpha order by last name): A. Architecture Technology AAS Degree Program by Department Chair James Ruggiero for appoint‐ ment of (1) Sandra Reicis, Administrative Manager/Marketing Assistant with Joy Kuebler Landscape Architect, PC; and (2) Crystal Surdyk, Associate Professor Interior Design with Villa Maria College. B. Dental Laboratory Technology AAS Degree Program by Department Head Peter DeMarco for appointment of (3) Noah Whiteford, Laboratory Manager with Pro‐Esthetics Dental Laboratory. C. Hospitality Management Program AAS, AOS and Certificate Programs by Department Chair Mark Wright for appointment of (4) Deborah Hartman Romaneo, Pastry Chef for Hutch’s Restaurant, Tempo, Remington Tavern and NYE Park Tavern; and reappointment of (5) Krista Van Wagner, Owner of Krista’s Caribbean Kitchen. D. Information Technology AAS Degree Program by Department Chair Louise Kowalski for appointment of (6) Russell Burgstahler, MIS Manager II, Assistant Vice President, Mortgage Infrastructure & Data Services with M & T Bank Corp.; (7) Robert Chavanne, Senior Technology Analyst & Solutions Architect with Sodexo; (8) Michael Dziadaszek, Software Engineer with Starline Inc.; (9) Jason Lavin, Systems Analyst III with Kaleida Health; (10) Claudia Padovano, Lead Data Security Analyst with Sodexo; (11) Peter Ronca, Executive with Shatter I.T. -

The Beautiful Warriors.Pdf

Minor Compositions Open Access Statement – Please Read This book is open access. This work is not simply an electronic book; it is the open access version of a work that exists in a number of forms, the traditional printed form being one of them. All Minor Compositions publications are placed for free, in their entirety, on the web. This is because the free and autonomous sharing of knowledges and experiences is important, especially at a time when the restructuring and increased centralization of book distribution makes it difficult (and expensive) to distribute radical texts effectively. The free posting of these texts does not mean that the necessary energy and labor to produce them is no longer there. One can think of buying physical copies not as the purchase of commodities, but as a form of support or solidarity for an approach to knowledge production and engaged research (particularly when purchasing directly from the publisher). The open access nature of this publication means that you can: • read and store this document free of charge • distribute it for personal use free of charge • print sections of the work for personal use • read or perform parts of the work in a context where no financial transactions take place However, it is against the purposes of Minor Compositions open access approach to: • gain financially from the work • sell the work or seek monies in relation to the distribution of the work • use the work in any commercial activity of any kind • profit a third party indirectly via use or distribution of the work • distribute in or through a commercial body (with the exception of academic usage within educational institutions) The intent of Minor Compositions as a project is that any surpluses generated from the use of collectively produced literature are intended to return to further the development and production of further publications and writing: that which comes from the commons will be used to keep cultivating those commons. -

Research Project Presentations and Public Performances

Joana Chicau [PT/NL] is a graphic designer, coder, researcher — with a background in dance. Her trans-disciplinary project interweaves media design and web environments with performance and choreographic practices. In her practice she researches the intersection of the body with the constructed, designed, programmed environment, aiming at in widening the ways in which digital sciences is presented and made accessible to the public. She has been actively participating and organizing events with performances involving multi-location collaborative coding, algorithmic improvisation, open discussions on gender equality and activism. Website: www.joanachicau.com 2016-now: Graphic Designer Freelancer; 2017-2018: Web and Graphic Designer at support team of e-learning department at TU Delft [brightspace-support.tudelft.nl] 2015-2016: Researcher at the Study Group Meeting at Casco, in Utrecht [www.wearethetimemachines.org] 2015-2016: Writer for the MoneyLab#2 and #3 conference organized by INC [networkcultures.org] 2015-2016: Graphic designer at Publishing Lab at the Institute of Network Cultures in Amsterdam [publishinglab.nl] 2014-2015: Graphic designer at Kinetic Vision, in Delft [skopeidigital.com/kv] 2014: Designer Intern at Ritator Design Studio, in Stockholm [ritator.com] Cross field competencies From digital to print; from responsive web design to experimental coding; from concept development to design production, research and curation. Experience with team work and both internal and external communication (with companies and clients); While being part of diverse work environments acquired knowledge in diverse work flows and methodologies, from design sprints to scrums, acquainted with coding dojo; as well programming iterations, such as agile, mob, and collaborative coding platforms such as GitHub. -

Something for Everyone: Using Digital Methods to Make Physical Goods*

Something for everyone: Using digital methods to make physical goods* by ginger coons A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Information University of Toronto Copyright by ginger coons 2016 Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license Something for everyone: Using digital methods to make physical goods* ginger coons Doctor of Philosophy 2016 Faculty of Information, University of Toronto Abstract In this dissertation I draw a link between the purported changes being wrought on society by the adoption of digital production technologies and previous waves of technological change in the production of goods. I use two case studies to provide detailed accounts of methods of production and development which use digital fabrication technologies to negotiate relationships between individuals and standards. The first case study, a collaborative Free/Libre Open Source Software development project, represents a kind of digital production which creates digital goods. The second case study looks at the digitally-aided fabrication of a physical good: 3D-printed sockets for prosthetic legs. I further argue that we need new frameworks for studying the intersection of the digital and the physical, or the inextricability of the two concepts. Scrutinizing the way mass methods of production almost always account for the needs of some kind of normative user, resulting in mis-fit for non-standard users, I then question arguments about mass-customization as a solution to mis-fit. One of the contentions I advance in this dissertation is that positioning mass production as necessarily harmful and marginalizing, while seeing mass customization as a solution, creates a counter-productive dichotomy. -

Libregraphicsmag 1.4 Lowquality.Pdf

Index 4 Masthead 6 Editor's Letter 7 Production Colophon 9 New Releases 10 Upcoming Events 12 Moral rights and the sil Open Font License Dave Crossland 14 Will these hands never be dirty? Eric Schrijver 16 Notebook 19 Small & useful 20 The finished and unfinished business of OpenLab esev Nelson Gonçalves and Maria Figueiredo 22 Best of svg 24 The Interview: Natanael Gama talks techno-fonts and the benefits of Libre Dave Crossland 26 Showcase 28 3D Printing 30 Baltan Cutter Eric de Haas 34 Paper.js Jonathan Puckey 38 Folds, impositions and gores: an interview with Tom Lechner Femke Snelting, Pierre Marchand and Ludivine Loiseau 43 ColorHug: filling the f/loss colour calibration void Richard Hughes 46 Resurrecting the noble plotter Manufactura Independente 48 Resource List 49 Glossary 1.4 4 MASTHEAD LIBRE GRAPHICS MAGAZINE 1.4 Masthead A Reader's Guide to Libre Graphics Magazine Editorial Team In this magazine, you may find concepts, words, ideas and Ana Carvalho [email protected] things which are new to you. Good. That means your ginger coons [email protected] horizons are expanding. The problem with that, of course, is Ricardo Lafuente [email protected] that sometimes, things with steep learning curves are less fun than those without. Copy editor Margaret Burnett That's why we're trying to flatten the learning curve. If, while reading Libre Graphics magazine, you encounter an unfamiliar Publisher word, project name, whatever it may be, chances are good ginger coons there's an explanation. Community Board At the back of this magazine, you'll find a glossary and Dave Crossland resource list. -

PRESSEMELDUNG Internationale Softwarekonferenz “Libre Graphics Meeting” 2019 Mi., 29.05

Ausgegeben am 03.05.2019 An die Vertreterinnen und Vertreter der Medien PRESSEMELDUN Internationa#e S"$t%are&onferenz (Libre Gra)hi+s Meeting” 2019 Mi., 29.05. So., 02.0/.2019 Veranstalter: 12 !nstitut $3r strategis+*e 4st*eti& Libre Gra)*i+s Meeting 2019 (LGM) LGM ist s"%"*# ein internati"nales Net'werk rund um $reie S"$tware im 7erei+* der gra8s+*en Gestaltung a#s au+* eine seit 200/ 9:*rli+* statt8ndende Entwi+kler*innen&"n$eren'. Stand"rte bewerben si+* 9:*rli+* um die Ausri+*tung des <"n me*reren *undert =eilne*mer*innen besu+*ten >a+*tre$$ens. ?u den bis*erigen 1"n$eren'stand"rten ge*@ren ="ront"- L"nd"n- Madrid- Montrea#- Ri" de Aaneiro und Wien. >3r 2019 *at 12 gemeinsam mit C71saar und D>1! $3r den Stand"rt Saarbrü+ken den ?us+*lag erha#ten und si+* gegen3ber Alternati<stand"rten (u.a. Mailand- Rom- 7uen"s Aires) durc*geset't. ?ie# der Veranstaltung ist es- die regi"nale Entwi+kler*innens'ene- saarländis+*e Unterne*men und Akteure aus 1ultur und Wissens+*a$t an'us)re+*en und ein'ubinden. 12 <erf"lgt damit einen bran+*en3bergrei$enden Ansat'- 'uma# das =*ema $reier S"$tware 'a*lrei+*e Ankn3)$ungs)unkte 'u =*emen der Digitalisierung bietet und da'u beitragen &ann- dass au+* im Saarland neue unterne*mens. und bran+*en3bergrei$ende Akteurs&"nste##ati"nen entste*en &@nnen. D$8'ie#le Erö$$nung . 29.05.2019- 12000 Uhr . Pinguss"n. eb:ude- C"*en'"llernstraEeF1e)lerstraEe- //11G Saarbrü+ken >"ren- V"rträge- B"rks*")s . -

Wednesday April 10Th

Wednesday April 10th 14:30 (workshop) Character animation in Synfig Konstantin Dmitriev morevnaproject.org/ In this workshop I'm going to demonstrate an approach for character animation in Synfig. This approach allows to produce simple but goodlooking animation very quickly using the special template. For more info please look at this demonstration http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d9d9a0zX5tg I am an animator with a special interest to libre and opensource software. Since 2001 I am teaching CG animation to kids and actively contributing to various opensource software projects since 2007. My main role in the opensource is leading the Morevna Project and helding administrator responsiblities in Synfig Studio development (http://synfig.org/). From time to time I like creating video tutorials about animation in Synfig, also doing some random contributions to its code. 17:00 (opening talk) Future Tools Femke Snelting, Laura Fernandez, Marcos Garcia 17:20 Programalaplaza: an online tool to write visual sketches for the Medialabprado Media facade Sergio GalÁn, Victor Diaz programalaplaza.medialabprado.es The MedialabPrado media facade is a 15m x 10m low resolution screen. It is an expensive infrastructure unique in the world. Until now, creating content for the facade has been a slow process, where apps has been done almost from scratch and with not so many people creating content for it. How to open this huge infrastructure for a massive and easy participation? Using the power of web technologies we designed and coded "Programalaplaza" (code the square) an online IDE which has all the elements to successfully develop and show visual pieces on the facade only using a web browser. -

Sommaire Passé Futur Présent

Le film d'animation libre "ZeMarmot": où en est-on? Posté par Jehan (page perso) le 15/04/16 à 11:38. Édité par 4 contributeurs. Modéré par ZeroHeure. Licence CC by-sa Tags : ardour, blender, gimp, film_d_animation, animation, zemarmot ZeMarmot est un film d'animation en 2D entièrement réalisé avec des logiciels libres, partiellement financé participativement, et diffusé sous licences Creative Commons paternité - partage à l'identique et Art Libre. Nous en avions déjà parlé sur LinuxFr.org, mais rappelons les points principaux: Logiciellement, nous utilisons GIMP pour le dessin, Blender VSE pour l'édition vidéo et Ardour pour l'édition audio. Le cœur de l'équipe ? Aryeom, réalisatrice coréenne de film d'animation, est l'artiste principale du projet ; moi-même, Jehan, développeur GIMP, suis le scénariste ainsi que le responsable technique ; enfin nous travaillons avec l'AMMD qui est en charge de la bande musicale du film. Nous approchons de la fin de la pré-production. Il est donc temps pour une petite mise-à-jour : que s'est-il passé depuis l'annonce du projet mi-2015 ? Les détails, ainsi que de nouvelles opportunités de nous soutenir, sont dans la seconde partie de la dépêche. Site officiel de ZeMarmot (50 clics) Blog de production (13 clics) Précédente annonce du financement sur Linuxfr (9 clics) Site officiel de GIMP (8 clics) Sommaire Passé Recherche Redesign Script Storyboard Animatique Développement de GIMP Logiciels d'animation Futur Itérations storyboard/animatique Musique Développement Production Transfert de connaissance Présent Libre Graphics Meeting GNOME.Asia Second voyage de recherche Financement Passé Recherche Notre vidéo d'accroche (teaser) fut réalisée en environ un mois, dans une frénésie de création rapide car nous voulions la sortir à temps pour Libre Graphics Meeting 2015.