Shifts in Domestication and Foreignisation in Translating Japanese Manga and Anime (Part Three)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why I Love Anime by Kaitlin Meaney I Figured I Would Take a Break

Why I love Anime By Kaitlin Meaney I figured I would take a break from writing about feelsy stuff to tell you about why I think anime is so awesome and that there is a lot to love about it. Also because I literally don’t have an anime to write about this week, at least nothing I’ve watched a whole series of yet. This is me taking a break this month. Anime has been a big part of my life ever since I was a child. My first exposures coming from Pokemon, Beyblade, Sailor Moon, Digimon, and Yu-Gi-Oh just to name a few. As I got older I found that the medium was a lot bigger than just the few I had seen in Saturday morning cartoons. In high school I was exposed to my first few subbed anime in the school anime club. I would say that I only truly realized my love for anime while in that club. Now I am an active member of the fandom watching anything that tickles my fancy. Anime is a much appreciated medium of television but it is vastly underrated. It’s regarded as one of the nerdiest thing right next to Dungeons and Dragons and/or video games. But there are some things about this medium that set it apart from the others. Something that makes it unique and creates the devoted fans that exist in abundance this day and age. I’ll be talking about what I personally love about anime and what makes it so cool in my eyes. -

Piracy Or Productivity: Unlawful Practices in Anime Fansubbing

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aaltodoc Publication Archive Aalto-yliopisto Teknillinen korkeakoulu Informaatio- ja luonnontieteiden tiedekunta Tietotekniikan tutkinto-/koulutusohjelma Teemu Mäntylä Piracy or productivity: unlawful practices in anime fansubbing Diplomityö Espoo 3. kesäkuuta 2010 Valvoja: Professori Tapio Takala Ohjaaja: - 2 Abstract Piracy or productivity: unlawful practices in anime fansubbing Over a short period of time, Japanese animation or anime has grown explosively in popularity worldwide. In the United States this growth has been based on copyright infringement, where fans have subtitled anime series and released them as fansubs. In the absence of official releases fansubs have created the current popularity of anime, which companies can now benefit from. From the beginning the companies have tolerated and even encouraged the fan activity, partly because the fans have followed their own rules, intended to stop the distribution of fansubs after official licensing. The work explores the history and current situation of fansubs, and seeks to explain how these practices adopted by fans have arisen, why both fans and companies accept them and act according to them, and whether the situation is sustainable. Keywords: Japanese animation, anime, fansub, copyright, piracy Tiivistelmä Piratismia vai tuottavuutta: laittomat toimintatavat animen fanikäännöksissä Japanilaisen animaation eli animen suosio maailmalla on lyhyessä ajassa kasvanut räjähdysmäisesti. Tämä kasvu on Yhdysvalloissa perustunut tekijänoikeuksien rikkomiseen, missä fanit ovat tekstittäneet animesarjoja itse ja julkaisseet ne fanikäännöksinä. Virallisten julkaisujen puutteessa fanikäännökset ovat luoneet animen nykyisen suosion, jota yhtiöt voivat nyt hyödyntää. Yhtiöt ovat alusta asti sietäneet ja jopa kannustaneet fanien toimia, osaksi koska fanit ovat noudattaneet omia sääntöjään, joiden on tarkoitus estää fanikäännösten levitys virallisen lisensoinnin jälkeen. -

Naoko Takeuchi

Naoko Takeuchi After going to the post-recording parties, I realized that Sailor Moon has come to life! I mean they really exist - Bunny and her friends!! I felt like a goddess who created mankind. It was so exciting. “ — Sailor Moon, Volume 3 Biography Naoko Takeuchi is best known as the creator of Sailor Moon, and her forte is in writing girls’ romance manga. Manga is the Japanese” word for Quick Facts “comic,” but in English it means “Japanese comics.” Naoko Takeuchi was born to Ikuko and Kenji Takeuchi on March 15, 1967 in the city * Born in 1967 of Kofu, Yamanashi Prefecture, Japan. She has one sibling: a younger brother named Shingo. Takeuchi loved drawing from a very young age, * Japanese so drawing comics came naturally to her. She was in the Astronomy manga (comic and Drawing clubs at her high school. At the age of eighteen, Takeuchi book) author debuted in the manga world while still in high school with the short story and song writer “Yume ja Nai no ne.” It received the 2nd Nakayoshi Comic Prize for * Creator of Newcomers. After high school, she attended Kyoritsu Yakka University. Sailor Moon While in the university, she published “Love Call.” “Love Call” received the Nakayoshi New Mangaka Award for new manga artists and was published in the September 1986 issue of the manga magazine Nakayo- shi Deluxe. Takeuchi graduated from Kyoritsu Yakka University with a degree in Chemistry specializing in ultrasound and medical electronics. Her senior thesis was entitled “Heightened Effects of Thrombolytic Ac- This page was researched by Em- tions Due to Ultrasound.” Takeuchi worked as a licensed pharmacist at ily Fox, Nadia Makousky, Amanda Polvi, and Taylor Sorensen for Keio Hospital after graduating. -

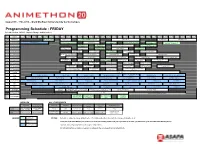

Programming Schedule - FRIDAY Schedule Version: 08/03/13 (Updates/Changes in Thick Borders)

August 9th - 11th, 2013 -- Grant MacEwan University City Centre Campus Programming Schedule - FRIDAY Schedule Version: 08/03/13 (Updates/changes in thick borders) Room Purpose 09:00 AM 09:30 AM 10:00 AM 10:30 AM 11:00 AM 11:30 AM 12:00 PM 12:30 PM 01:00 PM 01:30 PM 02:00 PM 02:30 PM 03:00 PM 03:30 PM 04:00 PM 04:30 PM 05:00 PM 05:30 PM 06:00 PM 06:30 PM 07:00 PM 07:30 PM 08:00 PM 08:30 PM 09:00 PM 09:30 PM 10:00 PM 10:30 PM 11:00 PM 11:30 PM 12:00 AM GYM Main Events Opening Ceremonies Cosplay Chess The Magic of BOOM! Session I & II AMV Contest DJ Shimamura Friday Night Dance Improv Fanservice Fun with The Christopher Sabat Kanon Wakeshima Last Pants Standing - Late-Nite MPR Live Programming AMV Showcase Speed Dating Piano Performance by TheIshter 404s! Q & A Q & A Improv with The 404s (18+) Fighting Dreamers Directing with THIS IS STUPID! Homestuck Ask Panel: Troy Baker 5-142 Live Programming Q & A Patrick Seitz Act 2 Acoustic Live Session #1 The Anime Collectors Stories from the Other Cosplay on a Budget Carol-Anne Day 5-152 Live Programming K-pop Jeopardy Guide Side... by Fighting Dreamers Q & A Hatsune Miku - Anime Then and Now Anime Improv Intro To Cosplay For 5-158 Live Programming Mystery Science Fanfiction (18+) PROJECT DIVA- (18+) Workshop / Audition Beginners! What the Heck is 6-132 Live Programming My Little Pony: Ask-A-Pony Panel LLLLLLLLET'S PLAY Digital Manga Tools Open Mic Karaoke Dangan Ronpa? 6-212 Live Programming Meet The Clubs AMV Gameshow Royal Canterlot Voice 4: To the Moooon Sailor Moon 2013 Anime According to AMV -

Gender and Audience Reception of English-Translated Manga

Girly Girls and Pretty Boys: Gender and Audience Reception of English-translated Manga June M. Madeley University of New Brunswick, Saint John Introduction Manga is the term used to denote Japanese comic books. The art styles and publishing industry are unique enough to warrant keeping this Japanese term for what has become transnational popular culture. This paper represents a preliminary analysis of interview data with manga readers. The focus of the paper is the discussion by participants of their favourite male and female characters as well as some general discussion of their reading practices. Males and females exhibit some reading preferences that are differentiated by gender. There is also evidence of gendered readings of male and female characters in manga. Manga in Japan are published for targeted gender and age groups. The broadest divisions are between manga for girls, shōjo, and manga for boys, shōnen. Unlike Canada and the USA, manga is mainstream reading in Japan; everyone reads manga (Allen and Ingulsrud 266; Grigsby 64; Schodt, Dreamland 21). Manga stories are first serialized in anthology magazines with a specific target audience. Weekly Shōnen Jump is probably the most well known because it serializes the manga titles that have been made into popular anime series on broadcast television in North America (and other transnational markets) such as Naruto and Bleach. Later, successful titles are compiled and reprinted as tankobon (small digest-sized paperback books). The tankobon is the format in which manga are translated into English and distributed by publishers with licensing rights purchased from the Japanese copyright holders. Translated manga are also increasingly available through online scanlations produced by fans who are able to translate Japanese to English. -

Exploring the Magical Girl Transformation Sequence with Flash Animation

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Art and Design Theses Ernest G. Welch School of Art and Design 5-10-2014 Releasing The Power Within: Exploring The Magical Girl Transformation Sequence With Flash Animation Danielle Z. Yarbrough Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/art_design_theses Recommended Citation Yarbrough, Danielle Z., "Releasing The Power Within: Exploring The Magical Girl Transformation Sequence With Flash Animation." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2014. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/art_design_theses/158 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Ernest G. Welch School of Art and Design at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art and Design Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RELEASING THE POWER WITHIN: EXPLORING THE MAGICAL GIRL TRANSFORMATION SEQUENCE WITH FLASH ANIMATION by DANIELLE Z. YARBROUGH Under the Direction of Dr. Melanie Davenport ABSTRACT This studio-based thesis explores the universal theme of transformation within the Magical Girl genre of Animation. My research incorporates the viewing and analysis of Japanese animations and discusses the symbolism behind transformation sequences. In addition, this study discusses how this theme can be created using Flash software for animation and discusses its value as a teaching resource in the art classroom. INDEX WORDS: Adobe Flash, Tradigital Animation, Thematic Instruction, Magical Girl Genre, Transformation Sequence RELEASING THE POWER WITHIN: EXPLORING THE MAGICAL GIRL TRANSFORMATION SEQUENCE WITH FLASH ANIMATION by DANIELLE Z. YARBROUGH A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Art Education In the College of Arts and Sciences Georgia State University 2014 Copyright by Danielle Z. -

Teen Calendar February 2020

Teen Calendar February 2020 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 1:00pm: Teen Anime Main Library Teens Club: I’ve Always Liked 2951 S 21st Dr. You, Kawaii Journaling Yuma, AZ 85364 & Mario Kart N64 (928) 373-6479 Tournament www.yumalibrary.org/teens 3 4 5 6 7 8 1:00pm: Teen Anime 4:00pm: Retro 4:00pm: New Teen 6:00pm: Dungeons and Club: Toradora, Sailor www.teenxing.blogspot.com Movie Mondays: Movies: Harriet Dragons Group A Moon Crystal & DIY E.T.: The Extra- Anime Valentine's Day Terrestrial Cards Library Hours: Monday-Thursday 10 11 12 13 14 15 4:00pm: Retro 4:00pm: 4:00pm DIY 1:00pm: Teen Anime 9:00am-9:00pm 11:00am: Video Movie Mondays: New Teen Movies: Valentine’s Day Cards Club: Snow White with Game & Card Red Hair, Kimi ni The Adams Family Friday & Saturday The Karate Kid Todoke & Anime Couples 6:00pm: Dungeons and Game Day (2019) Bingo 9:00am-5:00pm Dragons Group B Sunday CLOSED 17 18 19 20 21 22 Closed for 4:00pm: 4:00pm: Escape Room: 4:00pm: Just Dance 2:00pm: 3D Modeling Anti-Love Potion #9 3:00pm: Tech for Teens President’s Day New Teen Movies: Wii Tournament Open House Maleficent: Mistress 6:00pm: Dungeons and of Evil Dragons Group A 24 25 26 27 28 29 2:00pm: Build a Droid 4:00pm: 4:00pm: 6:00pm: Dungeons and 11:00am: Video Retro Movie New Teen Movies: Dragons Group B Game & Card Mondays: Ford v. Ferrari Game Day The Karate Kid II Teen Anime Club: This month theme is romantic anime! We will watch Snow White with Red Hair and Sailor Moon Crystal among other romance anime. -

Os Mangás E a Prática De Scanlation No Contexto De Convergência Midiática

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO CEARÁ INSTITUTO DE CULTURA E ARTE CURSO DE JORNALISMO RÔMULO OLIVEIRA BARBOSA OS MANGÁS E A PRÁTICA DE SCANLATION NO CONTEXTO DE CONVERGÊNCIA MIDIÁTICA FORTALEZA 2019 RÔMULO OLIVEIRA BARBOSA OS MANGÁS E A PRÁTICA DE SCANLATION NO CONTEXTO DE CONVERGÊNCIA MIDIÁTICA Monografia apresentada ao Curso de Comunicação Social da Universidade Federal do Ceará como requisito para a obtenção do grau de Bacharel em Comunicação Social - Jornalismo, sob a orientação do Prof. José Riverson Araújo Cysne Rios. Fortaleza 2019 ______________________________________________________________________ _____ Página reservada para ficha catalográfica. Utilize a ferramenta online Catalog! para elaborar a ficha catalográfica de seu trabalho acadêmico, gerando-a em arquivo PDF, disponível para download e/ou impressão. (http://www.fichacatalografica.ufc.br/) RÔMULO OLIVEIRA BARBOSA OS MANGÁS E A PRÁTICA DE SCANLATION NO CONTEXTO DE CONVERGÊNCIA MIDIÁTICA Esta monografia foi submetida ao Curso de Comunicação Social - Jornalismo da Universidade Federal do Ceará como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Bacharel. A citação de qualquer trecho desta monografia é permitida desde que feita de acordo com as normas da ética científica. Monografia apresentada à Banca Examinadora: _________________________________________________ Prof. Ph.D. José Riverson Araújo Cysne Rios (Orientador) Universidade Federal do Ceará _________________________________________________ Prof. M.e. Raimundo Nonato de Lima Universidade Federal do Ceará _________________________________________________ Prof. esp. Lauriberto Carneiro Braga Centro Universitário Estácio do Ceará Aos meus familiares e amigos AGRADECIMENTOS Dedico este trabalho primeiramente à minha família. Meu irmão Marcos Vinícius, meu pai Nilton Araújo, minha mãe Maria Neuda, que de maneira ousada e sempre contundente fez sempre o que esteve ao seu alcance para me educar e me dar o conforto de um lar. -

On Manga, Mimetics and the Feeling of (Reading A) Language

2017 | Capacious: Journal for Emerging Affect Inquiry 1 (1) CAPACIOUS On Manga, Mimetics and the Feeling of (Reading a) Language Toward a Situated Translational Practice Gretchen Jude UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA DAVIS Graphic novels, by combining images with printed words, engage readers in narrative experiences comparable to the immersive quality of cinema. The rich tradition of manga, Japan’s venerable and wide-ranging graphic narrative form, employs an array of graphical and linguistic strategies to engage readers, bodily as well as mentally and emotionally. Among these strategies, Japanese mimetics: a grammatical class of sound words, work efectively to transmit aural, tactile, and proprioceptive states. Yet most Japanese mimetics have no English equivalent and can only be expressed with phrase-length explanations or glosses; the somatic nature of mimetics thus resists translation. By grappling with the question of how to efectively express in English such translation-resistant linguistic forms, the author explores approaches to translation that attend to embodied and afective states such as those induced by mimetics. Experimental translational practices may thus attend to the afective and bodily-lived pressures felt when experiencing the in-between-ness of language(s). The structure of this paper accordingly follows the trajectory of a journey through (one reader’s) translation and translational practice. KEYWORDS Nomadic Translation, Manga, Scanlation, Mimetics, Nostalgia Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC BY 4.0) capaciousjournal.com | DOI: https://doi.org/10.22387/cap2016.3 36 On Manga, Mimetics and the Feeling of (Reading a) Language The Conditions of Translation: My Story On the eve of my return to the U.S. -

Intercultural Crossovers, Transcultural Flows: Manga/Comics

Intercultural Crossovers, Transcultural Flows: Manga/Comics (Global Manga Studies, vol. 2) Jaqueline Berndt, ed. Kyoto Seika University International Manga Research Center 2012 Table of Contents Introduction 1 Jaqueline BERNDT 1: Particularities of boys’ manga in the early 21st century: How NARUTO 9 differs from DRAGON BALL ITŌ Gō 2. Subcultural entrepreneurs, path dependencies and fan reactions: The 17 case of NARUTO in Hungary Zoltan KACSUK 3 .The NARUTO fan generation in Poland: An attempt at contextualization 33 Radosław BOLAŁEK 4. Transcultural Hybridization in Home-Grown German Manga 49 Paul M. MALONE 5. On the depiction of love between girls across cultures: comparing the 61 U.S.- American webcomic YU+ME: dream and the yuri manga “Maria- sama ga miteru” Verena MASER 6. Gekiga as a site of intercultural exchange: Tatsumi Yoshihiro’s A 73 Drifting Life Roman ROSENBAUM 7. The Eye of the Image: Transcultural characteristics and intermediality 93 in Urasawa Naoki’s transcultural narrative 20th Century Boys Felix GIESA & Jens MEINRENKEN 8. Cool Premedialisation as Symbolic Capital of Innovation: On 107 Intercultural Intermediality between Comics, Literature, Film, Manga, and Anime Thomas BECKER 9. Reading (and looking at) Mariko Parade-A methodological suggestion 119 for understanding contemporary graphic narratives Maaheen AHMED Epilogue 135 Steffi RICHTER Introduction Kyoto Seika University’s International Manga Research Center is supposed to organize one international conference per year. The first was held at the Kyoto International Manga Museum in December 2009,1 and the second at the Cultural Institute of Japan in Cologne, Germany, September 30 - October 2, 2010. This volume assembles about half of the then-given papers, mostly in revised version. -

MAD SCIENCE! Ab Science Inc

MAD SCIENCE! aB Science Inc. PROGRAM GUIDEBOOK “Leaders in Industry” WARNING! MAY CONTAIN: Vv Highly Evil Violations of Volatile Sentient :D Space-Time Materials Robots Laws FOOT table of contents 3 Letters from the Co-Chairs 4 Guests of Honor 10 Events 15 Video Programming 18 Panels & Workshops 28 Artists’ Alley 32 Dealers Room 34 Room Directory 35 Maps 41 Where to Eat 48 Tipping Guide 49 Getting Around 50 Rules 55 Volunteering 58 Staff 61 Sponsors 62 Fun & Games 64 Autographs APRIL 2-4, 2O1O 1 IN MEMORY OF TODD MACDONALD “We will miss and love you always, Todd. Thank you so much for being a friend, a staffer, and for the support you’ve always offered, selflessly and without hesitation.” —Andrea Finnin LETTERS FROM THE CO-CHAIRS Anime Boston has given me unique growth Hello everyone, welcome to Anime Boston! opportunities, and I have become closer to people I already knew outside of the convention. I hope you all had a good year, though I know most of us had a pretty bad year, what with the economy, increasing healthcare This strengthening of bonds brought me back each year, but 2010 costs and natural disasters (donate to Haiti!). At Anime Boston, is different. In the summer of 2009, Anime Boston lost a dear I hope we can provide you with at least a little enjoyment. friend and veteran staffer when Todd MacDonald passed away. We’ve been working long and hard to get composer Nobuo When Todd joined staff in 2002, it was only because I begged. Uematsu, most famous for scoring most of the music for the Few on staff imagined that our three-day convention was going Final Fantasy games as well as other Square Enix games such to be such an amazing success. -

“Traducción Indirecta De Onomatopeyas Japonesas Al Español En El Fansub: Un Estudio De Caso Del Manga Black Bird” TESIS Gu

UNIVERSIDAD DE GUANAJUATO División de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades Departamento de Lenguas Licenciatura en Enseñanza de Español como Segunda Lengua “Traducción indirecta de onomatopeyas japonesas al español en el fansub: un estudio de caso del manga Black Bird” TESIS Para obtener el grado de Licenciada en la Enseñanza del Español como Segunda Lengua PRESENTA Maricarmen Martínez Sandoval Directora de tesis Dra. Krisztina Zimányi Guanajuato, Gto, México Septiembre 2017 AGRADECIMIENTOS Por aquella pequeña niña a la que una vez le dijeron que no era capaz de ser lo que quería ser, por aquella pequeña yo que una vez creyó que podía alcanzar las estrellas y le fueron arrebatadas las raíces de sus sueños. Por todas las malas experiencias y los fracasos que estaban destinados a ocurrir para lograr cumplir una de mis más grandes metas en la vida. Por todo el miedo, la desconfianza, la baja autoestima y todas las sentencias ajenas de imposibilidad. Pero, sobre todo, por aquella niña que creció para convertirse en adulta y superó los obstáculos. Gracias a esos magníficos seres que estuvieron ahí para apoyarme; gracias a mis padres quienes me sostuvieron cada vez que mi determinación flaqueaba, gracias a mi hermana que siempre me proveía con una dosis de realidad, gracias a mis profesores que siempre me dieron el impulso que necesitaba para continuar e incluso gracias a mi mascota que me consolaba cuando yo pensaba que no lo iba a lograr. II ABSTRACT La onomatopeya en el cómic tiene la importancia de dar información al lector sobre el contexto, y hacerlo sentir dentro del mundo de la historia que se está narrando.