The Problematic Internationalization Strategy of the Japanese Manga

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPA : Redesigning Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. UPA : redesigning animation Bottini, Cinzia 2016 Bottini, C. (2016). UPA : redesigning animation. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/69065 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/69065 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 20:18:45 SGT UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND MEDIA 2016 UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI School of Art, Design and Media A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” Paul Klee, “Creative Credo” Acknowledgments When I started my doctoral studies, I could never have imagined what a formative learning experience it would be, both professionally and personally. I owe many people a debt of gratitude for all their help throughout this long journey. I deeply thank my supervisor, Professor Heitor Capuzzo; my cosupervisor, Giannalberto Bendazzi; and Professor Vibeke Sorensen, chair of the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for showing sincere compassion and offering unwavering moral support during a personally difficult stage of this Ph.D. I am also grateful for all their suggestions, critiques and observations that guided me in this research project, as well as their dedication and patience. My gratitude goes to Tee Bosustow, who graciously -

Imōto-Moe: Sexualized Relationships Between Brothers and Sisters in Japanese Animation

Imōto-Moe: Sexualized Relationships Between Brothers and Sisters in Japanese Animation Tuomas Sibakov Master’s Thesis East Asian Studies Faculty of Humanities University of Helsinki November 2020 Tiedekunta – Fakultet – Faculty Koulutusohjelma – Utbildningsprogram – Degree Programme Faculty of Humanities East Asian Studies Opintosuunta – Studieinriktning – Study Track East Asian Studies Tekijä – Författare – Author Tuomas Valtteri Sibakov Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Imōto-Moe: Sexualized Relationships Between Brothers and Sisters in Japanese Animation Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and Sivumäärä– Sidoantal – Number of pages Master’s Thesis year 83 November 2020 Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract In this work I examine how imōto-moe, a recent trend in Japanese animation and manga in which incestual connotations and relationships between brothers and sisters is shown, contributes to the sexualization of girls in the Japanese society. This is done by analysing four different series from 2010s, in which incest is a major theme. The analysis is done using visual analysis. The study concludes that although the series can show sexualization of drawn underage girls, reading the works as if they would posit either real or fictional little sisters as sexual targets. Instead, the analysis suggests that following the narrative, the works should be read as fictional underage girls expressing a pure feelings and sexuality, unspoiled by adult corruption. To understand moe, it is necessary to understand the history of Japanese animation. Much of the genres, themes and styles in manga and anime are due to Tezuka Osamu, the “god of manga” and “god of animation”. From the 1950s, Tezuka was influenced by Disney and other western animators at the time. -

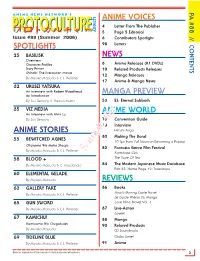

Protoculture Addicts

PA #88 // CONTENTS PA A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S ANIME VOICES 4 Letter From The Publisher PROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]-PROTOCULTURE ADDICTS 5 Page 5 Editorial Issue #88 (Summer 2006) 6 Contributors Spotlight SPOTLIGHTS 98 Letters 25 BASILISK NEWS Overview Character Profiles 8 Anime Releases (R1 DVDs) Story Primer 10 Related Products Releases Shinobi: The live-action movie 12 Manga Releases By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 17 Anime & Manga News 32 URUSEI YATSURA An interview with Robert Woodhead MANGA PREVIEW An Introduction By Zac Bertschy & Therron Martin 53 ES: Eternal Sabbath 35 VIZ MEDIA ANIME WORLD An interview with Alvin Lu By Zac Bertschy 73 Convention Guide 78 Interview ANIME STORIES Hitoshi Ariga 80 Making The Band 55 BEWITCHED AGNES 10 Tips from Full Moon on Becoming a Popstar Okusama Wa Maho Shoujo 82 Fantasia Genre Film Festival By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Sample fileKamikaze Girls 58 BLOOD + The Taste Of Tea By Miyako Matsuda & C. Macdonald 84 The Modern Japanese Music Database Part 35: Home Page 19: Triceratops 60 ELEMENTAL GELADE By Miyako Matsuda REVIEWS 63 GALLERY FAKE 86 Books Howl’s Moving Castle Novel By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Le Guide Phénix Du Manga 65 GUN SWORD Love Hina, Novel Vol. 1 By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 87 Live-Action Lorelei 67 KAMICHU! 88 Manga Kamisama Wa Chugakusei 90 Related Products By Miyako Matsuda CD Soundtracks 69 TIDELINE BLUE Otaku Unite! By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 91 Anime More on: www.protoculture-mag.com & www.animenewsnetwork.com 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ LETTER FROM THE PUBLISHER A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S PROTOCULTUREPROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]- ADDICTS Over seven years of writing and editing anime reviews, I’ve put a lot of thought into what a Issue #88 (Summer 2006) review should be and should do, as well as what is shouldn’t be and shouldn’t do. -

Retirement Strategy Fund 2060 Description Plan 3S DCP & JRA

Retirement Strategy Fund 2060 June 30, 2020 Note: Numbers may not always add up due to rounding. % Invested For Each Plan Description Plan 3s DCP & JRA ACTIVIA PROPERTIES INC REIT 0.0137% 0.0137% AEON REIT INVESTMENT CORP REIT 0.0195% 0.0195% ALEXANDER + BALDWIN INC REIT 0.0118% 0.0118% ALEXANDRIA REAL ESTATE EQUIT REIT USD.01 0.0585% 0.0585% ALLIANCEBERNSTEIN GOVT STIF SSC FUND 64BA AGIS 587 0.0329% 0.0329% ALLIED PROPERTIES REAL ESTAT REIT 0.0219% 0.0219% AMERICAN CAMPUS COMMUNITIES REIT USD.01 0.0277% 0.0277% AMERICAN HOMES 4 RENT A REIT USD.01 0.0396% 0.0396% AMERICOLD REALTY TRUST REIT USD.01 0.0427% 0.0427% ARMADA HOFFLER PROPERTIES IN REIT USD.01 0.0124% 0.0124% AROUNDTOWN SA COMMON STOCK EUR.01 0.0248% 0.0248% ASSURA PLC REIT GBP.1 0.0319% 0.0319% AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR 0.0061% 0.0061% AZRIELI GROUP LTD COMMON STOCK ILS.1 0.0101% 0.0101% BLUEROCK RESIDENTIAL GROWTH REIT USD.01 0.0102% 0.0102% BOSTON PROPERTIES INC REIT USD.01 0.0580% 0.0580% BRAZILIAN REAL 0.0000% 0.0000% BRIXMOR PROPERTY GROUP INC REIT USD.01 0.0418% 0.0418% CA IMMOBILIEN ANLAGEN AG COMMON STOCK 0.0191% 0.0191% CAMDEN PROPERTY TRUST REIT USD.01 0.0394% 0.0394% CANADIAN DOLLAR 0.0005% 0.0005% CAPITALAND COMMERCIAL TRUST REIT 0.0228% 0.0228% CIFI HOLDINGS GROUP CO LTD COMMON STOCK HKD.1 0.0105% 0.0105% CITY DEVELOPMENTS LTD COMMON STOCK 0.0129% 0.0129% CK ASSET HOLDINGS LTD COMMON STOCK HKD1.0 0.0378% 0.0378% COMFORIA RESIDENTIAL REIT IN REIT 0.0328% 0.0328% COUSINS PROPERTIES INC REIT USD1.0 0.0403% 0.0403% CUBESMART REIT USD.01 0.0359% 0.0359% DAIWA OFFICE INVESTMENT -

Piracy Or Productivity: Unlawful Practices in Anime Fansubbing

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aaltodoc Publication Archive Aalto-yliopisto Teknillinen korkeakoulu Informaatio- ja luonnontieteiden tiedekunta Tietotekniikan tutkinto-/koulutusohjelma Teemu Mäntylä Piracy or productivity: unlawful practices in anime fansubbing Diplomityö Espoo 3. kesäkuuta 2010 Valvoja: Professori Tapio Takala Ohjaaja: - 2 Abstract Piracy or productivity: unlawful practices in anime fansubbing Over a short period of time, Japanese animation or anime has grown explosively in popularity worldwide. In the United States this growth has been based on copyright infringement, where fans have subtitled anime series and released them as fansubs. In the absence of official releases fansubs have created the current popularity of anime, which companies can now benefit from. From the beginning the companies have tolerated and even encouraged the fan activity, partly because the fans have followed their own rules, intended to stop the distribution of fansubs after official licensing. The work explores the history and current situation of fansubs, and seeks to explain how these practices adopted by fans have arisen, why both fans and companies accept them and act according to them, and whether the situation is sustainable. Keywords: Japanese animation, anime, fansub, copyright, piracy Tiivistelmä Piratismia vai tuottavuutta: laittomat toimintatavat animen fanikäännöksissä Japanilaisen animaation eli animen suosio maailmalla on lyhyessä ajassa kasvanut räjähdysmäisesti. Tämä kasvu on Yhdysvalloissa perustunut tekijänoikeuksien rikkomiseen, missä fanit ovat tekstittäneet animesarjoja itse ja julkaisseet ne fanikäännöksinä. Virallisten julkaisujen puutteessa fanikäännökset ovat luoneet animen nykyisen suosion, jota yhtiöt voivat nyt hyödyntää. Yhtiöt ovat alusta asti sietäneet ja jopa kannustaneet fanien toimia, osaksi koska fanit ovat noudattaneet omia sääntöjään, joiden on tarkoitus estää fanikäännösten levitys virallisen lisensoinnin jälkeen. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

Imagined Identity and Cross-Cultural Communication in Yuri!!! on ICE Tien-Yi Chao National Taiwan University

ISSN: 2519-1268 Issue 9 (Summer 2019), pp. 59-87 DOI: 10.6667/interface.9.2019.86 Russia/Russians on Ice: Imagined Identity and Cross-cultural Communication in Yuri!!! on ICE tien-yi chao National Taiwan University Abstract Yuri!!! on ICE (2016; 2017) is a Japanese TV anime featuring multinational figure skaters com- peting in the ISU Grand Prix of Figure Skating Series. The three protagonists, including two Russian skaters Victor Nikiforov, and Yuri Purisetsuki (Юрий Плисецкий), and one Japanese skater Yuri Katsuki (勝生勇利), engage in extensive cross-cultural discourses. This paper aims to explore the ways in which Russian cultures, life style, and people are ‘glocalised’ in the anime, not only for the Japanese audience but also for fans around the world. It is followed by a brief study of Russian fans’ response to YOI’s display of Russian memes and Taiwanese YOI fan books relating to Russia and Russians in YOI. My reading of the above materials suggests that the imagined Russian identity in both the official anime production and the fan works can be regarded as an intriguing case of cross-cultural communication and cultural hybridisation. Keywords: Yuri!!! on ICE, Japanese ACG (animation/anime, comics, games), anime, cross-cul- tural communication, cultural hybridisation © Tien-Yi Chao This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. http://interface.ntu.edu.tw/ 59 Russia/Russians on Ice: Imagined Identity and Cross-cultural Communication in Yuri!!! on ICE Yuri!!! on ICE (ユーリ!!! on ICE; hereinafter referred to as YOI)1 is a TV anime2 broadcast in Japan between 5 October and 21 December 2016, featuring male figure skaters of various nationalities. -

The Formation of Temporary Communities in Anime Fandom: a Story of Bottom-Up Globalization ______

THE FORMATION OF TEMPORARY COMMUNITIES IN ANIME FANDOM: A STORY OF BOTTOM-UP GLOBALIZATION ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Fullerton ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Geography ____________________________________ By Cynthia R. Davis Thesis Committee Approval: Mark Drayse, Department of Geography & the Environment, Chair Jonathan Taylor, Department of Geography & the Environment Zia Salim, Department of Geography & the Environment Summer, 2017 ABSTRACT Japanese animation, commonly referred to as anime, has earned a strong foothold in the American entertainment industry over the last few decades. Anime is known by many to be a more mature option for animation fans since Western animation has typically been sanitized to be “kid-friendly.” This thesis explores how this came to be, by exploring the following questions: (1) What were the differences in the development and perception of the animation industries in Japan and the United States? (2) Why/how did people in the United States take such interest in anime? (3) What is the role of anime conventions within the anime fandom community, both historically and in the present? These questions were answered with a mix of historical research, mapping, and interviews that were conducted in 2015 at Anime Expo, North America’s largest anime convention. This thesis concludes that anime would not have succeeded as it has in the United States without the heavy involvement of domestic animation fans. Fans created networks, clubs, and conventions that allowed for the exchange of information on anime, before Japanese companies started to officially release anime titles for distribution in the United States. -

Oh My Goddess!: V. 16 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

OH MY GODDESS!: V. 16 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Kosuke Fujishima | 240 pages | 11 Jan 2011 | Dark Horse Comics,U.S. | 9781595825940 | English | Milwaukie, United States Oh My Goddess!: v. 16 PDF Book Light and Shadow: The kid plans to cause all time to stop and everything to stay eternally frozen in one time. Charlenia Kirkes rated it it was amazing Oct 21, Animage in Japanese. Vanguard: High School Arc Cont. Kodansha Manga Award — General. Overview Ever since a cosmic phone call brought the literal young goddess Belldandy into college student Keiichi's residence, his personal life has been turned upside down, sideways, and sometimes even into strange dimensions! Inara rated it really liked it Jan 21, Anime International Company. Lists with This Book. Other books in the series. A seal exists between the demon world and Earth, named the Gate to the Netherworld. Chapters Ah! Currently, no plans exist for licensing that special OVA episode. Volume Demons have similar class and license restrictions, and are accompanied by familiars instead of angels. It premiered in the November issue of Afternoon where it is still being serialized. Ryo-Ohki —present Oh My Goddess! Wikimedia Commons Wikiquote. Policenauts It was okay. Oh My Goddess!: v. 16 Writer These include the spirits of Money, Wind, Engine and such. There are no discussion topics on this book yet. Tamagotchi — Inazuma Eleven — Usaru-san Tamagotchi! This Fandom wiki is currently inactive. Tokyo , Japan : Tokuma Shoten. Released in concert with the OVA series in , [17] Smith has since stated that he saw the title as a play on "Oh my god! White Fox. -

Representations and Reality: Defining the Ongoing Relationship Between Anime and Otaku Cultures By: Priscilla Pham

Representations and Reality: Defining the Ongoing Relationship between Anime and Otaku Cultures By: Priscilla Pham Submitted to OCAD University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Contemporary Art, Design, and New Media Art Histories Toronto, Ontario, Canada, April 2021 © Priscilla Pham, 2021 Abstract This major research paper investigates the ongoing relationship between anime and otaku culture through four case studies; each study considers a single situation that demonstrates how this relationship changes through different interactions with representation. The first case study considers the early transmedia interventions that began to engage fans. The second uses Takashi Murakami’s theory of Superflat to connect the origins of the otaku with the interactions otaku have with representation. The third examines the shifting role of the otaku from that of consumer to producer by means of engagement with the hierarchies of perception, multiple identities, and displays of sexualities in the production of fan-created works. The final case study reflects on the 2.5D phenomenon, through which 2D representations are brought to 3D environments. Together, these case studies reveal the drivers of the otaku evolution and that the anime–otaku relationship exists on a spectrum that teeters between reality and representation. i Acknowledgements I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my primary advisor, Ala Roushan, for her continued support and confidence in my writing throughout this paper’s development. Her constructive advice, constant guidance, and critical insights helped me form this paper. Thank you to Dr. David McIntosh, my secondary reader, for his knowledge on anime and the otaku world, which allowed me to change my perspective of a world that I am constantly lost in. -

A Voice Against War

STOCKHOLMS UNIVERSITET Institutionen för Asien-, Mellanöstern- och Turkietstudier A Voice Against War Pacifism in the animated films of Miyazaki Hayao Kandidatuppsats i japanska VT 2018 Einar Schipperges Tjus Handledare: Ida Kirkegaard Innehållsförteckning Annotation ............................................................................................................................................... 3 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Aim of the study ............................................................................................................................ 5 1.2 Material ......................................................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Research question .......................................................................................................................... 5 1.4 Theory ........................................................................................................................................... 5 1.4.1 Textual analysis ...................................................................................................................... 5 1.4.2 Theory of animation, definition of animation ........................................................................ 6 1.5 Methodology ................................................................................................................................ -

Retaliation Lawsuit Hits SJSU, CSU

Tuesday, Volume 156 April 27, 2021 No. 35 SERVING SAN JOSE STATE UNIVERSITY SINCE 1934 WWW.SJSUNEWS.COM/SPARTAN_DAILY Retaliation lawsuit hits SJSU, CSU By Christina Casillas & Stephanie Lam email that stated the external investigation concluded ILL USTR STAFF WRITER & ASSISTANT NEWS EDITOR the recent and previous misconduct cases ATI ON BY are substantiated. “To the affected student-athletes and NICK YB A lawsuit filed against San Jose State and California State their families, I apologize for this breach ARR University officials was brought to light just after SJSU released of trust,” Papazian stated in the email. A its first public statement admitting wrongdoing for not “I am determined that we will learn thoroughly investigating sexual misconduct allegations against from the past and never repeat it.” the university’s former sports medicine director. Mashinchi said for a Swimming and diving head coach Sage Hopkins filed suit in “better understanding of the March 2021 to the Santa Clara County Superior Court against situation,” a frequently asked administrators including current Athletic Director Marie Tuite questions (FAQ) document for retaliating against him after ignoring his claims against Scott will be posted on the SJSU Shaw, according to the 93-page court documents obtained by For Your Information the Spartan Daily. webpage this week that Hopkins wrote a letter to SJSU President Mary Papazian details the December 2019 two months ago stating the administration has been trying to investigation. silence him, according to a Sunday Mercury News article. Mashinchi said the “Your administration attempted to bully and silence me in FAQ page will also explain a revolting and abusive attempt to silence the victims of Scott why a Title IX Procedural Shaw and protect those administrators’ roles in the cover-up Response Investigation is and enabling of this abuse,” Hopkins wrote in the letter.