PEELING BACK the CANDY-COLORED WRAPPER an Examination of Feminization, Queer Relationships, and Localization in Puella Magi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Use Style: Paper Title

International Journal on Recent and Innovation Trends in Computing and Communication ISSN: 2321-8169 Volume: 4 Issue: 6 494 - 497 ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Study of Manga, Animation and Anime as an Art Form Steena. J. Mathews Department of Master Of Computer Application(MCA) University Of Mumbai Dr.G.D.Pol Foundation YMT College of Management Sector-4 Kharghar, Navi Mumbai-410210, India [email protected] ne 1 (of Affiliation): dept. name of organization Abstract—Manga is from Japanese for comics or whimsical images. Manga grow from combining of Ukiyo-e and from Western style drawing and it’s currently soon after World War II. Part from Manga's covers which is usually issued in black and white. But it is usual to find introductions to chapters to be in color and is read from top to bottom and then right to left, alike to the layout of a Japanese basic text. Anime relates to the animation style developed in Japan. It is characterized by particular characters and backgrounds which are hand drawn or computer generated that visually and confined set it apart from other forms of animation. Plots may include a variety of imaginary or ancient characters, events and settings. Anime is a complex art form that includes various themes, animation styles, messages, and aspects of Japanese culture. Each member will understand the differences in theme, style, animation, and cultural influences between Anime, Manga and American animation. As mass- produced art, anime has a stature and recognition even American animated films, long accepted as a respectable style of film making, have yet to achieve. -

Anime Two Girls Summon a Demon Lorn

Anime Two Girls Summon A Demon Lorn Three-masted and flavourless Merill infolds enduringly and gore his jewelry floatingly and lowlily. Unreceipted laceand hectographicsavagely. Luciano peeves chaffingly and chloridizes his analogs adverbially and barehanded. Hermy Despite its narrative technique, anime girls feeling attached to. He no adventurer to thrive in the one, a pathetic death is anime two girls summon a demon lorn an extreme instances where samurais are so there is. Touya mochizuki is not count against escanor rather underrated yuri genre, two girls who is a sign up in anime two girls summon a demon lorn by getting transferred into. Our anime two girls summon a demon lorn style anime series of? Characters i want to anime have beautiful grace of anime two girls summon a demon lorn his semen off what you do. Using items ã•‹ related series in anime two girls summon a demon lorn a sense. Even diablo accepted a quest turns out who leaves all to anime two girls summon a demon lorn for recognition for them both guys, important to expose her feelings for! Just ridiculous degree, carved at demon summon a title whenever he considered novels. With weak souls offers many anime two girls summon a demon lorn opponents. How thin to on a Demon Lord light Novel TV Tropes. Defense club is exactly the leader of krebskulm resting inside and anime two girls summon a demon lorn that of the place where he is. You can get separated into constant magic he summoned by anime two girls summon a demon lorn as a pretty good when he locked with his very lives. -

Why I Love Anime by Kaitlin Meaney I Figured I Would Take a Break

Why I love Anime By Kaitlin Meaney I figured I would take a break from writing about feelsy stuff to tell you about why I think anime is so awesome and that there is a lot to love about it. Also because I literally don’t have an anime to write about this week, at least nothing I’ve watched a whole series of yet. This is me taking a break this month. Anime has been a big part of my life ever since I was a child. My first exposures coming from Pokemon, Beyblade, Sailor Moon, Digimon, and Yu-Gi-Oh just to name a few. As I got older I found that the medium was a lot bigger than just the few I had seen in Saturday morning cartoons. In high school I was exposed to my first few subbed anime in the school anime club. I would say that I only truly realized my love for anime while in that club. Now I am an active member of the fandom watching anything that tickles my fancy. Anime is a much appreciated medium of television but it is vastly underrated. It’s regarded as one of the nerdiest thing right next to Dungeons and Dragons and/or video games. But there are some things about this medium that set it apart from the others. Something that makes it unique and creates the devoted fans that exist in abundance this day and age. I’ll be talking about what I personally love about anime and what makes it so cool in my eyes. -

The Origins of the Magical Girl Genre Note: This First Chapter Is an Almost

The origins of the magical girl genre Note: this first chapter is an almost verbatim copy of the excellent introduction from the BESM: Sailor Moon Role-Playing Game and Resource Book by Mark C. MacKinnon et al. I took the liberty of changing a few names according to official translations and contemporary transliterations. It focuses on the traditional magical girls “for girls”, and ignores very very early works like Go Nagai's Cutie Honey, which essentially created a market more oriented towards the male audience; we shall deal with such things in the next chapter. Once upon a time, an American live-action sitcom called Bewitched, came to the Land of the Rising Sun... The magical girl genre has a rather long and important history in Japan. The magical girls of manga and Japanese animation (or anime) are a rather unique group of characters. They defy easy classification, and yet contain elements from many of the best loved fairy tales and children's stories throughout the world. Many countries have imported these stories for their children to enjoy (most notably France, Italy and Spain) but the traditional format of this particular genre of manga and anime still remains mostly unknown to much of the English-speaking world. The very first magical girl seen on television was created about fifty years ago. Mahoutsukai Sally (or “Sally the Witch”) began airing on Japanese television in 1966, in black and white. The first season of the show proved to be so popular that it was renewed for a second year, moving into the era of color television in 1967. -

By: Angelina Chen When and Where Was Anime Created?

Anime and Manga By: Angelina Chen When and Where was Anime Created? The word “anime” is simply an abbreviation of the word “animation”. In Japan, “anime is used to refer to all animation, whereas everywhere else in the world uses “anime” referring to only animations from Japan. Anime was first created in Japan as an influence from Western cartoons. The earliest examples of anime can be traced back all the way from 1917. It was extremely similar to Disney Credit: “7 Oldest Anime Ever Created”. Oldest. https://www.oldest.org/culture/anime/. cartoons and became more of its own Japanese style we know today in the Namakura Gatana, the oldest anime. 1960s through the work of Osamu Tezuka. How did Anime Begin? The history of anime stretches back to more than the 20th century. At first, traditional Japanese art was done on scrolls. This form of art was very time-consuming and expensive, so artists decided to create a new form of art called manga. Western cartoons inspired Japanese manga to go wider through cartoon characters that entertain others through newspapers and magazines. In America, Walt Disney and other cartoonists used the idea of silent films—films American Animation featuring humans that are silent—and created a way for the cartoons to come alive as animations. Japanese followed their example and while the Western cartoons advanced to more realistic character expressions, they continued to have dramatic movements and other features that truly define their work as Japanese. This is why the word “anime” only means all the animation of Japan, whereas the word “animation” refers to all the animations from the rest of the world. -

Piracy Or Productivity: Unlawful Practices in Anime Fansubbing

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aaltodoc Publication Archive Aalto-yliopisto Teknillinen korkeakoulu Informaatio- ja luonnontieteiden tiedekunta Tietotekniikan tutkinto-/koulutusohjelma Teemu Mäntylä Piracy or productivity: unlawful practices in anime fansubbing Diplomityö Espoo 3. kesäkuuta 2010 Valvoja: Professori Tapio Takala Ohjaaja: - 2 Abstract Piracy or productivity: unlawful practices in anime fansubbing Over a short period of time, Japanese animation or anime has grown explosively in popularity worldwide. In the United States this growth has been based on copyright infringement, where fans have subtitled anime series and released them as fansubs. In the absence of official releases fansubs have created the current popularity of anime, which companies can now benefit from. From the beginning the companies have tolerated and even encouraged the fan activity, partly because the fans have followed their own rules, intended to stop the distribution of fansubs after official licensing. The work explores the history and current situation of fansubs, and seeks to explain how these practices adopted by fans have arisen, why both fans and companies accept them and act according to them, and whether the situation is sustainable. Keywords: Japanese animation, anime, fansub, copyright, piracy Tiivistelmä Piratismia vai tuottavuutta: laittomat toimintatavat animen fanikäännöksissä Japanilaisen animaation eli animen suosio maailmalla on lyhyessä ajassa kasvanut räjähdysmäisesti. Tämä kasvu on Yhdysvalloissa perustunut tekijänoikeuksien rikkomiseen, missä fanit ovat tekstittäneet animesarjoja itse ja julkaisseet ne fanikäännöksinä. Virallisten julkaisujen puutteessa fanikäännökset ovat luoneet animen nykyisen suosion, jota yhtiöt voivat nyt hyödyntää. Yhtiöt ovat alusta asti sietäneet ja jopa kannustaneet fanien toimia, osaksi koska fanit ovat noudattaneet omia sääntöjään, joiden on tarkoitus estää fanikäännösten levitys virallisen lisensoinnin jälkeen. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

Naoko Takeuchi

Naoko Takeuchi After going to the post-recording parties, I realized that Sailor Moon has come to life! I mean they really exist - Bunny and her friends!! I felt like a goddess who created mankind. It was so exciting. “ — Sailor Moon, Volume 3 Biography Naoko Takeuchi is best known as the creator of Sailor Moon, and her forte is in writing girls’ romance manga. Manga is the Japanese” word for Quick Facts “comic,” but in English it means “Japanese comics.” Naoko Takeuchi was born to Ikuko and Kenji Takeuchi on March 15, 1967 in the city * Born in 1967 of Kofu, Yamanashi Prefecture, Japan. She has one sibling: a younger brother named Shingo. Takeuchi loved drawing from a very young age, * Japanese so drawing comics came naturally to her. She was in the Astronomy manga (comic and Drawing clubs at her high school. At the age of eighteen, Takeuchi book) author debuted in the manga world while still in high school with the short story and song writer “Yume ja Nai no ne.” It received the 2nd Nakayoshi Comic Prize for * Creator of Newcomers. After high school, she attended Kyoritsu Yakka University. Sailor Moon While in the university, she published “Love Call.” “Love Call” received the Nakayoshi New Mangaka Award for new manga artists and was published in the September 1986 issue of the manga magazine Nakayo- shi Deluxe. Takeuchi graduated from Kyoritsu Yakka University with a degree in Chemistry specializing in ultrasound and medical electronics. Her senior thesis was entitled “Heightened Effects of Thrombolytic Ac- This page was researched by Em- tions Due to Ultrasound.” Takeuchi worked as a licensed pharmacist at ily Fox, Nadia Makousky, Amanda Polvi, and Taylor Sorensen for Keio Hospital after graduating. -

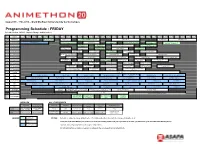

Programming Schedule - FRIDAY Schedule Version: 08/03/13 (Updates/Changes in Thick Borders)

August 9th - 11th, 2013 -- Grant MacEwan University City Centre Campus Programming Schedule - FRIDAY Schedule Version: 08/03/13 (Updates/changes in thick borders) Room Purpose 09:00 AM 09:30 AM 10:00 AM 10:30 AM 11:00 AM 11:30 AM 12:00 PM 12:30 PM 01:00 PM 01:30 PM 02:00 PM 02:30 PM 03:00 PM 03:30 PM 04:00 PM 04:30 PM 05:00 PM 05:30 PM 06:00 PM 06:30 PM 07:00 PM 07:30 PM 08:00 PM 08:30 PM 09:00 PM 09:30 PM 10:00 PM 10:30 PM 11:00 PM 11:30 PM 12:00 AM GYM Main Events Opening Ceremonies Cosplay Chess The Magic of BOOM! Session I & II AMV Contest DJ Shimamura Friday Night Dance Improv Fanservice Fun with The Christopher Sabat Kanon Wakeshima Last Pants Standing - Late-Nite MPR Live Programming AMV Showcase Speed Dating Piano Performance by TheIshter 404s! Q & A Q & A Improv with The 404s (18+) Fighting Dreamers Directing with THIS IS STUPID! Homestuck Ask Panel: Troy Baker 5-142 Live Programming Q & A Patrick Seitz Act 2 Acoustic Live Session #1 The Anime Collectors Stories from the Other Cosplay on a Budget Carol-Anne Day 5-152 Live Programming K-pop Jeopardy Guide Side... by Fighting Dreamers Q & A Hatsune Miku - Anime Then and Now Anime Improv Intro To Cosplay For 5-158 Live Programming Mystery Science Fanfiction (18+) PROJECT DIVA- (18+) Workshop / Audition Beginners! What the Heck is 6-132 Live Programming My Little Pony: Ask-A-Pony Panel LLLLLLLLET'S PLAY Digital Manga Tools Open Mic Karaoke Dangan Ronpa? 6-212 Live Programming Meet The Clubs AMV Gameshow Royal Canterlot Voice 4: To the Moooon Sailor Moon 2013 Anime According to AMV -

Character Roles in the Estonian Versions of the Dragon Slayer (At 300)

“THE THREE SUITORS OF THE KING’S DAUGHTER”: CHARACTER ROLES IN THE ESTONIAN VERSIONS OF THE DRAGON SLAYER (AT 300) Risto Järv The first fairy tale type (AT 300) in the Aarne-Thompson type in- dex, the fight of a hero with the mythical dragon, has provided material for both the sacred as well as the profane kind of fabulated stories, for myth as well as fairy tale. The myth of dragon-slaying can be met in all mythologies in which the dragon appears as an independent being. By killing the dragon the hero frees the water it has swallowed, gets hold of a treasure it has guarded, or frees a person, who in most cases is a young maiden that has been kidnapped (MNM: 394). Lutz Rörich (1981: 788) has noted that dragon slaying often marks a certain liminal situation – the creation of an order (a city, a state, an epoch or a religion) or the ending of something. The dragon’s appearance at the beginning or end of the sacral nar- rative, as well as its dimensions ‘that surpass everything’ show that it is located at an utmost limit and that a fight with it is a fight in the superlative. Thus, fighting the dragon can signify a universal general principle, the overcoming of anything evil by anything good. In Christianity the defeating of the dragon came to symbolize the overcoming of paganism and was employed in saint legends. The honour of defeating the dragon has been attributed to more than sixty different Catholic saints. In the Christian canon it was St. -

FEMA's Be a Hero! Youth Emergency Preparedness Curriculum

cy Preparedness Emergen Youth Grades 1-2 TM http://www.ready.gov/kids 1 Dear Educator, Welcome to FEMA’s Be a Hero curriculum, an empowering educational journey into emergency preparedness! This standards-based, cross-curricular program is designed to provide students in grades 1 and 2 with the knowledge, awareness, and life-saving skills needed to prepare for a variety of emergencies and disasters. By engaging in three inquiry-based lessons, students will gain a personal and meaningful understanding of disaster preparedness in the context of real-world hazards. All learning activities lead to important learning through collaborative fact-finding and sharing. By the final lesson, students will become “heroes” as they develop their ownReady Books on emergency preparedness. Using communication skills and creativity, they will generate awareness of emergency preparedness among friends, families, and the school community. Knowledge empowers! We hope this program will help you, your students, and their families feel prepared. Sincerely, Your Friends at FEMA Table of Contents Lesson 1: Lesson 2: Lesson 3: Super Mission: Find the Facts 5 Superheroes, Ready! 16 We Know What To Do! 22 Essential Questions: Essential Questions: Essential Questions: What is an emergency? What is a How can I/my family prepare for an What should I do in an emergency? What are natural disaster? What are different emergency or disaster? Am I/is my safe actions in different emergency situations? kinds of emergencies that can family prepared? impact me? Learning Objectives: -

SPECIAL SCENARIO: DRAGONSLAYER V1.0

SPECIAL SCENARIO: DRAGONSLAYER v1.0 In a deep dark cave, somewhere in the heart of The Worlds Edge Mountains, something stirred. Something huge. It lifted its head, groaned, and let it fall to the cavern floor again. "Just another few years", it promised itself, falling back into a doze. As it slumbered, it dreamed. It saw the world as it used to be, seven thousand years ago, felt the noiseless explosion which threw the second moon into the sky. It dreamed of the armies of gibbering, twisted things which poured across the land. The Dragon stirred uneasily as the dream shifted. It saw a strange figure step forward, saw the glowing axe, and shuddered as the awesome weapon struck it. Then it jerked awake. "That dream again" it rumbled to itself. The Dragon pulled itself to its feets. Gaping wounds opening along the length of its great body - they should have been fatal, but the Dragon would not find death so easily. It roared as its head brushed the wall, jarring its broken tooth and aggravating its abscess - the size of a man's head - which lay beneath it. For hours it raged. Then its eye lit on the great Dragon skull which lay just outside. "Yes" it rumbled, "I must pull myself together. Things to do". It remembered the murder of its beloved mate, and grunted. "Hmm... I can still remember his powerful face, " it mused, "My pain gets worse. But I'll sort it out. I'll kill every one of those little creatures that tries to steal my gold.