Sharmaphd1987vol2.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prayer-Guide-South-Asia.Pdf

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & Unreached People Groups = LR-UPGs = of South Asia Joshua Project data, www.joshuaproject.net (India DPG is separate) Western edition To order prayer resources or for inquiries, contact email: [email protected] I give credit & thanks to Create International for permission to use their PG photos. 2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & LR-UPGs = Least-Reached-Unreached People Groups of South Asia = this DPG SOUTH ASIA SUMMARY: 873 total People Groups; 733 UPGs The 6 countries of South Asia (India; Bangladesh; Nepal; Sri Lanka; Bhutan; Maldives) has 3,178 UPGs = 42.89% of the world's total UPGs! We must pray and reach them! India: 2,717 total PG; 2,445 UPGs; (India is reported in separate Daily Prayer Guide) Bangladesh: 331 total PG; 299 UPGs; Nepal: 285 total PG; 275 UPG Sri Lanka: 174 total PG; 79 UPGs; Bhutan: 76 total PG; 73 UPGs; Maldives: 7 total PG; 7 UPGs. Downloaded from www.joshuaproject.net in September 2020 LR-UPG definition: 2% or less Evangelical & 5% or less Christian Frontier (FR) definition: 0% to 0.1% Christian Why pray--God loves lost: world UPGs = 7,407; Frontier = 5,042. Color code: green = begin new area; blue = begin new country "Prayer is not the only thing we can can do, but it is the most important thing we can do!" Luke 10:2, Jesus told them, "The harvest is plentiful, but the workers are few. Ask the Lord of the harvest, therefore, to send out workers into his harvest field." Why Should We Pray For Unreached People Groups? * Missions & salvation of all people is God's plan, God's will, God's heart, God's dream, Gen. -

J:\GRS=Formating Journals\EA 3

Manjur Ali FORGOTTEN AT THE MARGIN : MUSLIM MANUAL SCAVENGERS Manual scavenging has been thrust upon a community who is then persuaded to be happy with its own marginality. In the Indian context, where division of labour of an individual is decided by his caste, this lack of economic alternative should be construed as a major principle of casteism. It is not just a ‘division of labour’, but also the “division of labourer”. It justifies manual scavenging in the name of ‘job’. Despite all the laws against caste practices, it’s most inhuman manifestation i.e. manual scavenging is still practiced in India. To deal with such a “dehumanizing practice” and “social stigma” the Union government passed a law known as Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Bill, 2013. This Bill will override the previous one as it had “not proved adequate in eliminating the twin evils of insanitary latrines and manual scavenging from the country.” It is in this context, that this paper would like to deal with Muslim manual scavengers, a little known entity in social science. The first question this paper would like to discuss is about the caste among Indian Muslims despite no sanction from the religion. Secondly, this paper shall deal with Muslim manual scavengers, an Arzal biradari, including their social history. This section will try to bring forth the socio-economic context of Muslim manual scavengers who live an ‘undignified’ life. Third section will deal with the subject of inaccessibility of scheme benefit meant for all manual scavengers? What has been the role of State in providing a dignified life to its citizens? A critical analysis of the movement against manual scavenging shall also be covered. -

Punjab Part Iv

Census of India, 1931 VOLUME ,XVII PUNJAB PART IV. ADMINISTRATIVE VOLlJME BY KHA~ AHMAD HASAN KHAN, M.A., K.S., SUPERINTENDENT OF CENSUS OPERATIONS, PUNJAB & DELHI. Lahore FmN'l'ED AT THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING PRESS, PUNJAB. 1933 Revised L.ist of Agents for the Sale of Punja b Government Pu hlications. ON THE CONTINENT AND UNITED KINGDOM. Publications obtainable either direct from the High Oommissioner for India. at India House, Aldwych. London. W. O. 2. or through any book seller :- IN INDIA. The GENERAL MANAGER, "The Qaumi Daler" and the Union Press, Amritsar. Messrs. D. B.. TARAPOREWALA. SONS & Co., Bombay. Messrs. W. NEWMAN & 00., Limite:>d, Calolltta. Messrs. THAOKER SPINK & Co., Calcutta. Messrs. RAMA KaIsHN A. & SONS, Lahore The SEORETARY, Punjab Religiolls Book Sooiety, Lahore. The University Book Agency, Kaoheri Road, Labore. L. RAM LAL SURI, Proprietor, " The Students' Own Agency," Lahore. L. DEWAN CHAND, Proprietor, The Mercantile Press, Lahore. The MANAGER, Mufid-i-'Am Press. Lahore. The PROPRIETOR, Punjab Law BOQk Mart, Lahore. Thp MANAGING PROPRIETOR. The Commercial Book Company, Lahore. Messrs. GOPAL SINGH SUB! & Co., Law Booksellers and Binders, Lahore. R. S. JAln\.A. Esq., B.A., B.T., The Students' Popular Dep6t, Anarkali, Lahore. Messrs. R. CAl\IBRAY & Co •• 1l.A., Halder La.ne, BowbazlU' P.O., Calcutta. Messrs. B. PARIKH & Co. Booksellers and Publishers, Narsinhgi Pole. Baroda. • Messrs. DES BROTHERS, Bo(.ksellers and Pnblishers, Anarkali, Lahore. The MAN AGER. The Firoz Book Dep6t, opposite Tonga Stand of Lohari Gate, La.hore. The MANAGER, The English Book Dep6t. Taj Road, Agra. ·The MANAGING PARTNER, The Bombay Book Depbt, Booksellers and Publishers, Girgaon, Bombay. -

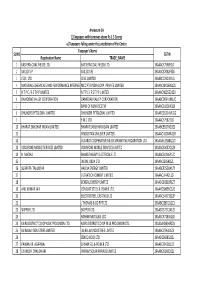

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

Annexure-1A 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores a) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the Centre Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 EASTERN COAL FIELDS LTD. EASTERN COAL FIELDS LTD. 19AAACE7590E1ZI 2 SAIL (D.S.P) SAIL (D.S.P) 19AAACS7062F6Z6 3 CESC LTD. CESC LIMITED 19AABCC2903N1ZL 4 MATERIALS CHEMICALS AND PERFORMANCE INTERMEDIARIESMCC PTA PRIVATE INDIA CORP.LIMITED PRIVATE LIMITED 19AAACM9169K1ZU 5 N T P C / F S T P P LIMITED N T P C / F S T P P LIMITED 19AAACN0255D1ZV 6 DAMODAR VALLEY CORPORATION DAMODAR VALLEY CORPORATION 19AABCD0541M1ZO 7 BANK OF NOVA SCOTIA 19AAACB1536H1ZX 8 DHUNSERI PETGLOBAL LIMITED DHUNSERI PETGLOBAL LIMITED 19AAFCD5214M1ZG 9 E M C LTD 19AAACE7582J1Z7 10 BHARAT SANCHAR NIGAM LIMITED BHARAT SANCHAR NIGAM LIMITED 19AABCB5576G3ZG 11 HINDUSTAN UNILEVER LIMITED 19AAACH1004N1ZR 12 GUJARAT COOPERATIVE MILKS MARKETING FEDARATION LTD 19AAAAG5588Q1ZT 13 VODAFONE MOBILE SERVICES LIMITED VODAFONE MOBILE SERVICES LIMITED 19AAACS4457Q1ZN 14 N MADHU BHARAT HEAVY ELECTRICALS LTD 19AAACB4146P1ZC 15 JINDAL INDIA LTD 19AAACJ2054J1ZL 16 SUBRATA TALUKDAR HALDIA ENERGY LIMITED 19AABCR2530A1ZY 17 ULTRATECH CEMENT LIMITED 19AAACL6442L1Z7 18 BENGAL ENERGY LIMITED 19AADCB1581F1ZT 19 ANIL KUMAR JAIN CONCAST STEEL & POWER LTD.. 19AAHCS8656C1Z0 20 ELECTROSTEEL CASTINGS LTD 19AAACE4975B1ZP 21 J THOMAS & CO PVT LTD 19AABCJ2851Q1Z1 22 SKIPPER LTD. SKIPPER LTD. 19AADCS7272A1ZE 23 RASHMI METALIKS LTD 19AACCR7183E1Z6 24 KAIRA DISTRICT CO-OP MILK PRO.UNION LTD. KAIRA DISTRICT CO-OP MILK PRO.UNION LTD. 19AAAAK8694F2Z6 25 JAI BALAJI INDUSTRIES LIMITED JAI BALAJI INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACJ7961J1Z3 26 SENCO GOLD LTD. 19AADCS6985J1ZL 27 PAWAN KR. AGARWAL SHYAM SEL & POWER LTD. 19AAECS9421J1ZZ 28 GYANESH CHAUDHARY VIKRAM SOLAR PRIVATE LIMITED 19AABCI5168D1ZL 29 KARUNA MANAGEMENT SERVICES LIMITED 19AABCK1666L1Z7 30 SHIVANANDAN TOSHNIWAL AMBUJA CEMENTS LIMITED 19AAACG0569P1Z4 31 SHALIMAR HATCHERIES LIMITED SHALIMAR HATCHERIES LTD 19AADCS6537J1ZX 32 FIDDLE IRON & STEEL PVT. -

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for All People Groups & LR-Unreached People Groups = LR-Upgs

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & LR-Unreached People Groups = LR-UPGs - of INDIA Source: Joshua Project data, www.joshuaproject.net Western edition To order prayer resources or for inquiries, contact email: [email protected] I give credit & thanks to Create International for permission to use their PG photos. 2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & LR-UPGs = Least-Reached-Unreached People Groups of India INDIA SUMMARY: 2,717 total People Groups; 2,445 LR-UPG India has 1/3 of all UPGs in the world; the most of any country LR-UPG definition: 2% or less Evangelical & 5% or less Christian Frontier (FR) definition: 0% to 0.1% Christian Why pray--God loves lost: world UPGs = 7,407; Frontier = 5,042. Color code: green = begin new area; blue = begin new country Downloaded from www.joshuaproject.net in September 2020 * * * "Prayer is not the only thing we can can do, but it is the most important thing we can do!" * * * India ISO codes are used for some Indian states as follows: AN = Andeman & Nicobar. JH = Jharkhand OD = Odisha AP = Andhra Pradesh+Telangana JK = Jammu & Kashmir PB = Punjab AR = Arunachal Pradesh KA = Karnataka RJ = Rajasthan AS = Assam KL = Kerala SK = Sikkim BR = Bihar ML = Meghalaya TN = Tamil Nadu CT = Chhattisgarh MH = Maharashtra TR = Tripura DL = Delhi MN = Manipur UT = Uttarakhand GJ = Gujarat MP = Madhya Pradesh UP = Uttar Pradesh HP = Himachal Pradesh MZ = Mizoram WB = West Bengal HR = Haryana NL = Nagaland Why Should We Pray For Unreached People Groups? * Missions & salvation of all people is God's plan, God's will, God's heart, God's dream, Gen. -

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Abdul in Bangladesh Bagdi (Hindu traditions) in Bangladesh Population: 30,000 Population: 89,000 World Popl: 66,200 World Popl: 2,990,000 Total Countries: 3 Total Countries: 2 People Cluster: South Asia Muslim - other People Cluster: South Asia Dalit - other Main Language: Bengali Main Language: Bengali Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Hinduism Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 0.00% Evangelicals: Unknown % Chr Adherents: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.29% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net Source: India Missions Association www.joshuaproject.net Source: Isudas "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Baidya (Hindu traditions) in Bangladesh Bairagi (Hindu traditions) in Bangladesh Population: 132,000 Population: 216,000 World Popl: 415,000 World Popl: 3,999,000 Total Countries: 2 Total Countries: 4 People Cluster: South Asia Hindu - other People Cluster: South Asia Hindu - other Main Language: Bengali Main Language: Bengali Main Religion: Hinduism Main Religion: Hinduism Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: Unknown % Evangelicals: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.07% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible Source: Isudas www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Anonymous "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for -

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Adi Andhra in India Adi Dravida in India Population: 307,000 Population: 8,598,000 World Popl: 307,800 World Popl: 8,598,000 Total Countries: 2 Total Countries: 1 People Cluster: South Asia Dalit - other People Cluster: South Asia Dalit - other Main Language: Telugu Main Language: Tamil Main Religion: Hinduism Main Religion: Hinduism Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: Unknown % Evangelicals: Unknown % Chr Adherents: 0.86% Chr Adherents: 0.09% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible Source: Anonymous www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Dr. Nagaraja Sharma / Shuttersto "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Agariya (Hindu traditions) in India Aguri in India Population: 208,000 Population: 516,000 World Popl: 208,000 World Popl: 517,300 Total Countries: 1 Total Countries: 2 People Cluster: South Asia Tribal - other People Cluster: South Asia Hindu - other Main Language: Agariya Main Language: Bengali Main Religion: Hinduism Main Religion: Hinduism Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: Unknown % Evangelicals: Unknown % Chr Adherents: 0.29% Chr Adherents: 0.11% Scripture: Translation Started Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Bethany World Prayer Center Source: Gerald Roberts "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for -

Uttar Pradesh Upgs 2018

State People Group Language Religion Population % Christian Uttar Pradesh Abdul Urdu Islam 4910 0 Uttar Pradesh Agamudaiyan Tamil Hinduism 30 0 Uttar Pradesh Agamudaiyan Nattaman Tamil Hinduism 30 0 Uttar Pradesh Agaria (Hindu traditions) Agariya Hinduism 29770 0 Uttar Pradesh Agaria (Muslim traditions) Urdu Islam 6430 0 Uttar Pradesh Ager (Hindu traditions) Kannada Hinduism 860 0 Uttar Pradesh Aghori Hindi Hinduism 21460 0 Uttar Pradesh Agri Marathi Hinduism 930 0 Uttar Pradesh Ahar Hindi Hinduism 1432140 0 Uttar Pradesh Aheria Hindi Hinduism 135160 0 Uttar Pradesh Ahmadi Urdu Islam 33150 0 Uttar Pradesh Anantpanthi Hindi Hinduism 610 0 Uttar Pradesh Ansari Urdu Islam 4544320 0 Uttar Pradesh Apapanthi Hindi Hinduism 27250 0 Uttar Pradesh Arab Arabic, Mesopotamian SpoKen Islam 90 0 Uttar Pradesh Arain (Hindu traditions) Hindi Hinduism 730 0 Uttar Pradesh Arain (Muslim traditions) Urdu Islam 57550 0 Uttar Pradesh Arakh Hindi Hinduism 375490 0 Uttar Pradesh Arora (Hindu traditions) Hindi Hinduism 19740 0 Uttar Pradesh Arora (SiKh traditions) Punjabi, Eastern Other / Small 17000 0 Uttar Pradesh Atari Urdu Islam 50 0 Uttar Pradesh Atishbaz Urdu Islam 2850 0 Uttar Pradesh BadaiK Sadri Hinduism 430 0 Uttar Pradesh Badhai (Hindu traditions) Hindi Hinduism 2461740 0 Uttar Pradesh Badhai (Muslim traditions) Urdu Islam 531520 0 Uttar Pradesh Badhi (Hindu traditions) Hindi Hinduism 7350 0 Uttar Pradesh Badhi (Muslim traditions) Urdu Islam 28340 0 Uttar Pradesh BadhiK Hindi Hinduism 15330 0 Uttar Pradesh Bagdi (Hindu traditions) Bengali Hinduism 4420 -

Of INDIA Source: Joshua Project Data, 2019 Western Edition Introduction Page I INTRODUCTION & EXPLANATION

Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & Unreached People Groups = LR-UPGs - of INDIA Source: Joshua Project data, www.joshuaproject.net 2019 Western edition Introduction Page i INTRODUCTION & EXPLANATION All Joshua Project people groups & “Least Reached” (LR) / “Unreached People Groups” (UPG) downloaded in August 2018 are included. Joshua Project considers LR & UPG as those people groups who are less than 2 % Evangelical and less than 5 % total Christian. The statistical data for population, percent Christian (all who consider themselves Christian), is Joshua Project computer generated as of August 24, 2018. This prayer guide is good for multiple years (2018, 2019, etc.) as there is little change (approx. 1.4% growth) each year. ** AFTER 2018 MULTIPLY POPULATION FIGURES BY 1.4 % ANNUAL GROWTH EACH YEAR. The JP-LR column lists those people groups which Joshua Project lists as “Least Reached” (LR), indicated by Y = Yes. White rows shows people groups JP lists as “Least Reached” (LR) or UPG, while shaded rows are not considered LR people groups by Joshua Project. For India ISO codes are used for some Indian states as follows: AN = Andeman & Nicobar. JH = Jharkhand OD = Odisha AP = Andhra Pradesh+Telangana JK = Jammu & Kashmir PB = Punjab AR = Arunachal Pradesh KA = Karnataka RJ = Rajasthan AS = Assam KL = Kerala SK = Sikkim BR = Bihar ML = Meghalaya TN = Tamil Nadu CT = Chhattisgarh MH = Maharashtra TR = Tripura DL = Delhi MN = Manipur UT = Uttarakhand GJ = Gujarat MP = Madhya Pradesh UP = Uttar Pradesh HP = Himachal Pradesh MZ = Mizoram WB = West Bengal HR = Haryana NL = Nagaland Introduction Page ii UNREACHED PEOPLE GROUPS IN INDIA AND SOUTH ASIA Mission leaders with Lausanne Committee for World Evangelization (LCWE) meeting in Chicago in 1982 developed this official definition of a PEOPLE GROUP: “a significantly large ethnic / sociological grouping of individuals who perceive themselves to have a common affinity to one another [on the basis of ethnicity, language, tribe, caste, class, religion, occupation, location, or a combination]. -

Karnataka Upgs 2018

State People Group Language Religion Population Christian % Karnataka Adi Karnataka Kannada Hinduism 3660660 4.83819858 Karnataka Agamudaiyan Tamil Hinduism 22440 0 Karnataka Agamudaiyan Mukkulattar Tamil Hinduism 40 0 Karnataka Agamudaiyan Nattaman Tamil Hinduism 17710 0 Karnataka Agani Kodava Hinduism 480 0 Karnataka Ager (Hindu traditions) Kannada Hinduism 8690 0 Karnataka Aghori Hindi Hinduism 40 0 Karnataka Agri Marathi Hinduism 560 0 Karnataka Ajila Malayalam Hinduism 3730 0 Karnataka Ajna Hindi Hinduism 80 0 Karnataka Alambadi Kurichchan Kurichiya Hinduism 1460 0 Karnataka Ambalavasi Malayalam Hinduism 8430 0 Karnataka Ambalavasi Tottiyan Naicker Tamil Hinduism 150 0 Karnataka Ambattan Tamil Hinduism 710 0 Karnataka Amma Kodaga Kodava Hinduism 1980 0 Karnataka Anamuk Telugu Hinduism 580 0 Karnataka Andh Marathi Hinduism 1250 0 Karnataka Anduran Konkani Hinduism 2480 0 Karnataka Ansari Urdu Islam 328880 0 Karnataka Anuppan Kannada Hinduism 340 0 Karnataka Arab Arabic Islam 220 0 Karnataka Arandan Aranadan Hinduism 70 0 Karnataka Arasu Kannada Hinduism 43920 0 Karnataka Aray Mala Telugu Hinduism 710 0 Karnataka Arayan Malayalam Hinduism 1560 0 Karnataka Arora (Sikh traditions) Punjabi, Eastern Other / Small 850 0 Karnataka Arunthathiyar Telugu Hinduism 3440 0 Karnataka Arwa Mala Tamil Hinduism 450 0 Karnataka Assamese (Muslim traditions) Assamese Islam 20 0 Karnataka Atari Urdu Islam 90 0 Karnataka Ayri Kodava Hinduism 210 0 Karnataka Ayyanavar Malayalam Hinduism 140 0 Karnataka Badaga Badaga Hinduism 19520 0.15368852 Karnataka Badhai -

Contemporary Lucknow: Life with 'Too Much History'

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal 11 | 2015 Contemporary Lucknow: Life with ‘Too Much History’ Raphael Susewind and Christopher B. Taylor (dir.) Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/samaj/3908 DOI: 10.4000/samaj.3908 ISSN: 1960-6060 Publisher Association pour la recherche sur l'Asie du Sud (ARAS) Electronic reference Raphael Susewind and Christopher B. Taylor (dir.), South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 11 | 2015, « Contemporary Lucknow: Life with ‘Too Much History’ » [Online], Online since 18 June 2015, connection on 20 March 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/samaj/3908 ; DOI : https:// doi.org/10.4000/samaj.3908 This text was automatically generated on 20 March 2020. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. 1 SAMAJ-EASAS Series Series editors: Margret Frenz and Roger Jeffery. image This thematic issue is the third in a series of issues jointly co-edited by SAMAJ and the European Association for South Asian Studies (EASAS). More on our partnership with EASAS here. South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 11 | 2015 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction. Islamicate Lucknow Today: Historical Legacy and Urban Aspirations Raphael Susewind and Christopher B. Taylor Urban Mythologies and Urbane Islam: Refining the Past and Present in Colonial-Era Lucknow Justin Jones Jagdish, Son of Ahmad: Dalit Religion and Nominative Politics in Lucknow Joel Lee Muslim Women’s Rights Activists’ Visibility: Stretching the Gendered Boundaries of the Public Space in the City of Lucknow Mengia Hong Tschalaer Madrasas and Social Mobility in the Religious Economy: The Case of Nadwat al-’Ulama in Lucknow Christopher B. -

Oc Caste List in Telangana Pdf

Oc caste list in telangana pdf Continue This is a complete list of Muslim communities in India (OBCs) that are recognized in the Indian Constitution as other backward classes, a term used to classify socially and educationally disadvantaged classes. The central list of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana below is a list of Muslim communities to which the Indian government has granted status to other backward classes in the states of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. Casta/Community Resolution No. and date No. 37 Mehtar 12011/68/93-BCC (C ) dt. September 10, 1993 and 12011/9/2004-BCC dt. 16 January 2006 No43 Dudekula Laddaf, Pinjari or Nurbash (Muslim) 12011/68/93-BCC (C ) dt. 10 September 1993 No62 Arekatika, Katika, Kuresh (Muslim butchers) 12011/68/93-BCC (C ) dt. September 10, 1993 and 12011/4/2002-BCC dt. 13 January 2004 No33 (Muslim Butchers) 12011/68/93-BCC (C ) dt. September 10, 93 and 12011/4/2002-BCC dt. On 13 January 2004, the State list lists the following list of Muslim communities to which the Andhra Pradesh State Government and the Karnataka State Government have granted the status of other backward classes. [4] 1. Achukattalawndlu, Singali, Sinhamvallu, Achupanivallu, Achukattuwaru, Achukatlawandlu. 2. Attar Saibulu, Attarollo 3. Dhobi Muslim / Muslim Dhobi / Dhobi Musalman, Turka Chakla or Turka Sakala, Turaka Chakali, Tulukka Vannan, Tsakalas, Sakalas or Chakalas, Muslim Rajakas 4. Alvi, Alvi Sayyen, Shah Alvi, Alvi, Alvi Sayed, Darvesh, Shah 5. Garadi Muslim, Garadi Saibulu, Pamulavallu, Kani-Kattuvalla, Garadoll, Garadig 6. Gosangi Muslim, Faker Sayebulu 7. Guddy Eluguvallu, Elugu Bantuvall, Musalman Kilu Gurralavalla 8.