J:\GRS=Formating Journals\EA 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prayer-Guide-South-Asia.Pdf

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & Unreached People Groups = LR-UPGs = of South Asia Joshua Project data, www.joshuaproject.net (India DPG is separate) Western edition To order prayer resources or for inquiries, contact email: [email protected] I give credit & thanks to Create International for permission to use their PG photos. 2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & LR-UPGs = Least-Reached-Unreached People Groups of South Asia = this DPG SOUTH ASIA SUMMARY: 873 total People Groups; 733 UPGs The 6 countries of South Asia (India; Bangladesh; Nepal; Sri Lanka; Bhutan; Maldives) has 3,178 UPGs = 42.89% of the world's total UPGs! We must pray and reach them! India: 2,717 total PG; 2,445 UPGs; (India is reported in separate Daily Prayer Guide) Bangladesh: 331 total PG; 299 UPGs; Nepal: 285 total PG; 275 UPG Sri Lanka: 174 total PG; 79 UPGs; Bhutan: 76 total PG; 73 UPGs; Maldives: 7 total PG; 7 UPGs. Downloaded from www.joshuaproject.net in September 2020 LR-UPG definition: 2% or less Evangelical & 5% or less Christian Frontier (FR) definition: 0% to 0.1% Christian Why pray--God loves lost: world UPGs = 7,407; Frontier = 5,042. Color code: green = begin new area; blue = begin new country "Prayer is not the only thing we can can do, but it is the most important thing we can do!" Luke 10:2, Jesus told them, "The harvest is plentiful, but the workers are few. Ask the Lord of the harvest, therefore, to send out workers into his harvest field." Why Should We Pray For Unreached People Groups? * Missions & salvation of all people is God's plan, God's will, God's heart, God's dream, Gen. -

The People of India

LIBRARY ANNFX 2 CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ^% Cornell University Library DS 421.R59 1915 The people of India 3 1924 024 114 773 Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924024114773 THE PEOPLE OF INDIA =2!^.^ Z'^JiiS- ,SIH HERBERT ll(i 'E MISLEX, K= CoIoB a , ( THE PEOPLE OF INDIA w SIR HERBERT RISLEY, K.C.I.E., C.S.I. DIRECTOR OF ETHNOGRAPHY FOR INDIA, OFFICIER d'aCADEMIE, FRANCE, CORRESPONDING MEMBER OF THE ANTHROPOLOGICAL SOCIETIES OF ROME AND BERLIN, AND OF THE ANTHROPOLOGICAL INSTITUTE OF GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND SECOND EDITION, EDITED BY W. CROOKE, B.A. LATE OF THE INDIAN CIVIL SERVICE "/« ^ood sooth, 7tiy masters, this is Ho door. Yet is it a little window, that looketh upon a great world" WITH 36 ILLUSTRATIONS AND AN ETHNOLOGICAL MAP OF INDIA UN31NDABL? Calcutta & Simla: THACKER, SPINK & CO. London: W, THACKER & CO., 2, Creed Lane, E.C. 191S PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED, LONDON AND BECCLES. e 7/ /a£ gw TO SIR WILLIAM TURNER, K.C.B. CHIEF AMONG ENGLISH CRANIOLOGISTS THIS SLIGHT SKETCH OF A LARGE SUBJECT IS WITH HIS PERMISSION RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION In an article on "Magic and Religion" published in the Quarterly Review of last July, Mr. Edward Clodd complains that certain observations of mine on the subject of " the impersonal stage of religion " are hidden away under the " prosaic title " of the Report on the Census of India, 1901. -

Contempt and Labour: an Exploration Through Muslim Barbers of South Asia

religions Article Contempt and Labour: An Exploration through Muslim Barbers of South Asia Safwan Amir Madras Institute of Development Studies, University of Madras, Chennai 600020, India; [email protected] Received: 9 September 2019; Accepted: 4 November 2019; Published: 6 November 2019 Abstract: This article explores historical shifts in the ways the Muslim barbers of South Asia are viewed and the intertwined ways they are conceptualised. Tracing various concepts, such as caste identity, and their multiple links to contempt, labour and Islamic ethical discourses and practices, this article demonstrates shifting meanings of these concepts and ways in which the Muslim barbers of Malabar (in southwest India) negotiate religious and social histories as well as status in everyday life. The aim was to link legal and social realms by considering how bodily comportment of barbers and pious Muslims intersect and diverge. Relying on ethnographic fieldwork among Muslim barbers of Malabar and their oral histories, it becomes apparent that status is negotiated in a fluid community where professional contempt, multiple attitudes about modernity and piety crosscut one another to inform local perceptions of themselves or others. This paper seeks to avoid the presentation of a teleology of past to present, binaries distinguishing professionals from quacks, and the pious from the scorned. The argument instead is that opposition between caste/caste-like practices and Islamic ethics is more complex than an essentialised dichotomy would convey. Keywords: barber; Ossan; caste; Islam; contempt; labour; Mappila; Makti Thangal; Malabar; South Asia 1. Introduction The modern nation-state of India has maintained an ambiguous relationship with caste and minority religions especially concerning reservation policies in various state and non-state sectors. -

Compliance Or Defiance? the Case of Dalits and Mahadalits

Kunnath, Compliance or defiance? COMPLIANCE OR DEFIANCE? THE CASE OF DALITS AND MAHADALITS GEORGE KUNNATH Introduction Dalits, who remain at the bottom of the Indian caste hierarchy, have resisted social and economic inequalities in various ways throughout their history.1 Their struggles have sometimes taken the form of the rejection of Hinduism in favour of other religions. Some Dalit groups have formed caste-based political parties and socio-religious movements to counter upper-caste domination. These caste-based organizations have been at the forefront of mobilizing Dalit communities in securing greater benefits from the Indian state’s affirmative action programmes. In recent times, Dalit organizations have also taken to international lobbying and networking to create wider platforms for the promotion of Dalit human rights and development. Along with protest against the caste system, Dalit history is also characterized by accommodation and compliance with Brahmanical values. The everyday Dalit world is replete with stories of Dalit communities consciously or unconsciously adopting upper-caste beliefs and practices. They seem to internalize the negative images and representations of themselves and their castes that are held and propagated by the dominant groups. Dalits are also internally divided by caste, with hierarchical rankings. They themselves thus often seem to reinforce and even reproduce the same system and norms that oppress them. This article engages with both compliance and defiance by Dalit communities. Both these concepts are central to any engagement with populations living in the context of oppression and inequality. Debates in gender studies, colonial histories and subaltern studies have engaged with the simultaneous existence of these contradictory processes. -

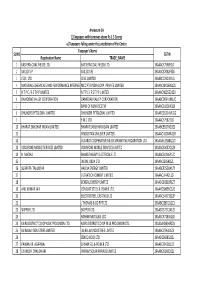

M.Phil Students

M.Phil Students Likely date of Availling Funding Name of the students Supervisor/ Co- Supervisor/Co- Enrollment No./ Registration Date of S.NO School Centre Name of Student Topic/Title of dissertation completion of Fellowship Agency of (in hindi ) Supervisor Supervisor (in Hindi) Photo ID No. Registration M.Phil Yes/No Fellowship 1 SLL&CS CCSEAS Aditya Kumar Pandey आ�द配य कुमार पा赍डे Not Decided Zero Year 16/59/MC/003 24283 4.08.2016 21.7.2019 Plan 2 SLL&CS CCSEAS Biatrisha Mukhopadhyay Not Decided Course Work 16/59/MC/001 27037 1.08.2016 21.7.2018 YES �बया�त्रसा मुखोपा鵍याय Fellowship 3 SLL&CS CCSEAS Shomia Biswas शो�मया �व�वास Not Decided Zero Year 16/59/MC/002 22165 1.08.2016 21.7.2019 4 SLL&CS CCSEAS Snigdha Konar िन嵍धा कोनार Not Decided Course Work 15/59/MC/001 28484 18.07.2016 21.7.2018 YES JRF Eine kritische Analyse der Mensch – Tier Prof. Sadhana 5 SLL&CS CGS Nidhi Mathur . Beziehung in Hermann Hesses Märchen 15/53/MG/003 22648 28.7.2015 July, 2017 yes UGC JRF �न�ध माथुर Naithani प्रोफ साधना नातानी “Der Zwerg” und “Vogel.” Die Darstellung der Protogonistinnen in “ Häutungen. Autobiografische Prof. Madhu 6 SLL&CS CGS Mr. Shaliesh Kumar Ray . Aufzeichnungen. Gedichte. Träume. 15/53/MG/001 26022 28.7.2015 July, 2017 yes UGC JRF शैलेश कुमार रे Sahni प्रोफ मधु साहनी Analysen” Von Verena Stefan und “ Die Liebhaberunnen” von Elfriede Jelinek Prof. -

Caste, Kinship and Sex Ratios in India

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES CASTE, KINSHIP AND SEX RATIOS IN INDIA Tanika Chakraborty Sukkoo Kim Working Paper 13828 http://www.nber.org/papers/w13828 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 March 2008 We thank Bob Pollak, Karen Norberg, David Rudner and seminar participants at the Work, Family and Public Policy workshop at Washington University for helpful comments and discussions. We also thank Lauren Matsunaga and Michael Scarpati for research assistance and Cassie Adcock and the staff of the South Asia Library at the University of Chicago for their generous assistance in data collection. We are also grateful to the Weidenbaum Center and Washington University (Faculty Research Grant) for research support. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2008 by Tanika Chakraborty and Sukkoo Kim. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Caste, Kinship and Sex Ratios in India Tanika Chakraborty and Sukkoo Kim NBER Working Paper No. 13828 March 2008 JEL No. J12,N35,O17 ABSTRACT This paper explores the relationship between kinship institutions and sex ratios in India at the turn of the twentieth century. Since kinship rules varied by caste, language, religion and region, we construct sex-ratios by these categories at the district-level using data from the 1901 Census of India for Punjab (North), Bengal (East) and Madras (South). -

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for All People Groups & Unreached People

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & Unreached People Groups = LR-UPGs = of South Asia Joshua Project data, www.joshuaproject.net (India DPG is separate) AGWM Western edition I give credit & thanks to Create International for permission to use their PG photos. 2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & LR-UPGs = Least-Reached-Unreached People Groups of South Asia = this DPG SOUTH ASIA SUMMARY: 873 total People Groups; 733 UPGs The 6 countries of South Asia (India; Bangladesh; Nepal; Sri Lanka; Bhutan; Maldives) has 3,178 UPGs = 42.89% of the world's total UPGs! We must pray and reach them! India: 2,717 total PG; 2,445 UPGs; (India is reported in separate Daily Prayer Guide) Bangladesh: 331 total PG; 299 UPGs; Nepal: 285 total PG; 275 UPG Sri Lanka: 174 total PG; 79 UPGs; Bhutan: 76 total PG; 73 UPGs; Maldives: 7 total PG; 7 UPGs. Downloaded from www.joshuaproject.net in September 2020 LR-UPG definition: 2% or less Evangelical & 5% or less Christian Frontier (FR) definition: 0% to 0.1% Christian Why pray--God loves lost: world UPGs = 7,407; Frontier = 5,042. Color code: green = begin new area; blue = begin new country "Prayer is not the only thing we can can do, but it is the most important thing we can do!" Luke 10:2, Jesus told them, "The harvest is plentiful, but the workers are few. Ask the Lord of the harvest, therefore, to send out workers into his harvest field." Why Should We Pray For Unreached People Groups? * Missions & salvation of all people is God's plan, God's will, God's heart, God's dream, Gen. -

The Musalman Races Found in Sindh

A SHORT SKETCH, HISTORICAL AND TRADITIONAL, OF THE MUSALMAN RACES FOUND IN SINDH, BALUCHISTAN AND AFGHANISTAN, THEIR GENEALOGICAL SUB-DIVISIONS AND SEPTS, TOGETHER WITH AN ETHNOLOGICAL AND ETHNOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT, BY SHEIKH SADIK ALÍ SHER ALÍ, ANSÀRI, DEPUTY COLLECTOR IN SINDH. PRINTED AT THE COMMISSIONER’S PRESS. 1901. Reproduced By SANI HUSSAIN PANHWAR September 2010; The Musalman Races; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 1 DEDICATION. To ROBERT GILES, Esquire, MA., OLE., Commissioner in Sindh, This Volume is dedicated, As a humble token of the most sincere feelings of esteem for his private worth and public services, And his most kind and liberal treatment OF THE MUSALMAN LANDHOLDERS IN THE PROVINCE OF SINDH, ВY HIS OLD SUBORDINATE, THE COMPILER. The Musalman Races; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 2 PREFACE. In 1889, while I was Deputy Collector in the Frontier District of Upper Sindh, I was desired by B. Giles, Esquire, then Deputy Commissioner of that district, to prepare a Note on the Baloch and Birahoi tribes, showing their tribal connections and the feuds existing between their various branches, and other details. Accordingly, I prepared a Note on these two tribes and submitted it to him in May 1890. The Note was revised by me at the direction of C. E. S. Steele, Esquire, when he became Deputy Commissioner of the above district, and a copy of it was furnished to him. It was revised a third time in August 1895, and a copy was submitted to H. C. Mules, Esquire, after he took charge of the district, and at my request the revised Note was printed at the Commissioner-in-Sindh’s Press in 1896, and copies of it were supplied to all the District and Divisional officers. -

Punjab Part Iv

Census of India, 1931 VOLUME ,XVII PUNJAB PART IV. ADMINISTRATIVE VOLlJME BY KHA~ AHMAD HASAN KHAN, M.A., K.S., SUPERINTENDENT OF CENSUS OPERATIONS, PUNJAB & DELHI. Lahore FmN'l'ED AT THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING PRESS, PUNJAB. 1933 Revised L.ist of Agents for the Sale of Punja b Government Pu hlications. ON THE CONTINENT AND UNITED KINGDOM. Publications obtainable either direct from the High Oommissioner for India. at India House, Aldwych. London. W. O. 2. or through any book seller :- IN INDIA. The GENERAL MANAGER, "The Qaumi Daler" and the Union Press, Amritsar. Messrs. D. B.. TARAPOREWALA. SONS & Co., Bombay. Messrs. W. NEWMAN & 00., Limite:>d, Calolltta. Messrs. THAOKER SPINK & Co., Calcutta. Messrs. RAMA KaIsHN A. & SONS, Lahore The SEORETARY, Punjab Religiolls Book Sooiety, Lahore. The University Book Agency, Kaoheri Road, Labore. L. RAM LAL SURI, Proprietor, " The Students' Own Agency," Lahore. L. DEWAN CHAND, Proprietor, The Mercantile Press, Lahore. The MANAGER, Mufid-i-'Am Press. Lahore. The PROPRIETOR, Punjab Law BOQk Mart, Lahore. Thp MANAGING PROPRIETOR. The Commercial Book Company, Lahore. Messrs. GOPAL SINGH SUB! & Co., Law Booksellers and Binders, Lahore. R. S. JAln\.A. Esq., B.A., B.T., The Students' Popular Dep6t, Anarkali, Lahore. Messrs. R. CAl\IBRAY & Co •• 1l.A., Halder La.ne, BowbazlU' P.O., Calcutta. Messrs. B. PARIKH & Co. Booksellers and Publishers, Narsinhgi Pole. Baroda. • Messrs. DES BROTHERS, Bo(.ksellers and Pnblishers, Anarkali, Lahore. The MAN AGER. The Firoz Book Dep6t, opposite Tonga Stand of Lohari Gate, La.hore. The MANAGER, The English Book Dep6t. Taj Road, Agra. ·The MANAGING PARTNER, The Bombay Book Depbt, Booksellers and Publishers, Girgaon, Bombay. -

1 CENTRAL LIST of Obcs for the STATE of JHARKHAND Entry No

CENTRAL LIST OF OBCs FOR THE STATE OF JHARKHAND Entry No Caste/ Community Resolution No. & Date 1. Abdal 12015/2/2007-B.C.C. dt. 18/08/2010 2. Aghori 12015/2/2007-B.C.C. dt. 18/08/2010 3. Amaat 12015/2/2007-B.C.C. dt. 18/08/2010 4. Bagdi 12015/2/2007-B.C.C. dt. 18/08/2010 5. Bakho (Muslim) 12015/2/2007-B.C.C. dt. 18/08/2010 6. Banpar 12015/2/2007-B.C.C. dt. 18/08/2010 7. Barai 12015/2/2007-B.C.C. dt. 18/08/2010 Barhai, Vishwakarma 12015/2/2007-BCC dt. 18/08/2010 8. 12015/13/2010-B.C.II. dt. 08/12/2011 9. Bari 12015/2/2007-BCC dt. 18/08/2010 10. Beldar 12015/2/2007-B.C.C. dt. 18/08/2010 11. Bhar 12015/2/2007-B.C.C. dt. 18/08/2010 12. Bhaskar 12015/2/2007-B.C.C. dt. 18/08/2010 Bhat, Bhatt, Bhat (Muslim) 12015/2/2007-BCC dt. 18/08/2010 13. 12015/13/2010-B.C.II. Dt. 08/12/2011 14. Bhathiara (Muslim) 12015/2/2007-BCC dt. 18/08/2010 15. Bind 12015/2/2007-B.C.C. dt. 18/08/2010 16. Bhuihar, Bhuiyar 12015/2/2007-B.C.C. dt. 18/08/2010 17. Chain, Chayeen 12015/2/2007-B.C.C. dt. 18/08/2010 18. Chapota 12015/2/2007-B.C.C. dt. 18/08/2010 19. Chandrabanshi (Kahar) 12015/2/2007-B.C.C. -

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

Annexure-1A 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores a) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the Centre Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 EASTERN COAL FIELDS LTD. EASTERN COAL FIELDS LTD. 19AAACE7590E1ZI 2 SAIL (D.S.P) SAIL (D.S.P) 19AAACS7062F6Z6 3 CESC LTD. CESC LIMITED 19AABCC2903N1ZL 4 MATERIALS CHEMICALS AND PERFORMANCE INTERMEDIARIESMCC PTA PRIVATE INDIA CORP.LIMITED PRIVATE LIMITED 19AAACM9169K1ZU 5 N T P C / F S T P P LIMITED N T P C / F S T P P LIMITED 19AAACN0255D1ZV 6 DAMODAR VALLEY CORPORATION DAMODAR VALLEY CORPORATION 19AABCD0541M1ZO 7 BANK OF NOVA SCOTIA 19AAACB1536H1ZX 8 DHUNSERI PETGLOBAL LIMITED DHUNSERI PETGLOBAL LIMITED 19AAFCD5214M1ZG 9 E M C LTD 19AAACE7582J1Z7 10 BHARAT SANCHAR NIGAM LIMITED BHARAT SANCHAR NIGAM LIMITED 19AABCB5576G3ZG 11 HINDUSTAN UNILEVER LIMITED 19AAACH1004N1ZR 12 GUJARAT COOPERATIVE MILKS MARKETING FEDARATION LTD 19AAAAG5588Q1ZT 13 VODAFONE MOBILE SERVICES LIMITED VODAFONE MOBILE SERVICES LIMITED 19AAACS4457Q1ZN 14 N MADHU BHARAT HEAVY ELECTRICALS LTD 19AAACB4146P1ZC 15 JINDAL INDIA LTD 19AAACJ2054J1ZL 16 SUBRATA TALUKDAR HALDIA ENERGY LIMITED 19AABCR2530A1ZY 17 ULTRATECH CEMENT LIMITED 19AAACL6442L1Z7 18 BENGAL ENERGY LIMITED 19AADCB1581F1ZT 19 ANIL KUMAR JAIN CONCAST STEEL & POWER LTD.. 19AAHCS8656C1Z0 20 ELECTROSTEEL CASTINGS LTD 19AAACE4975B1ZP 21 J THOMAS & CO PVT LTD 19AABCJ2851Q1Z1 22 SKIPPER LTD. SKIPPER LTD. 19AADCS7272A1ZE 23 RASHMI METALIKS LTD 19AACCR7183E1Z6 24 KAIRA DISTRICT CO-OP MILK PRO.UNION LTD. KAIRA DISTRICT CO-OP MILK PRO.UNION LTD. 19AAAAK8694F2Z6 25 JAI BALAJI INDUSTRIES LIMITED JAI BALAJI INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACJ7961J1Z3 26 SENCO GOLD LTD. 19AADCS6985J1ZL 27 PAWAN KR. AGARWAL SHYAM SEL & POWER LTD. 19AAECS9421J1ZZ 28 GYANESH CHAUDHARY VIKRAM SOLAR PRIVATE LIMITED 19AABCI5168D1ZL 29 KARUNA MANAGEMENT SERVICES LIMITED 19AABCK1666L1Z7 30 SHIVANANDAN TOSHNIWAL AMBUJA CEMENTS LIMITED 19AAACG0569P1Z4 31 SHALIMAR HATCHERIES LIMITED SHALIMAR HATCHERIES LTD 19AADCS6537J1ZX 32 FIDDLE IRON & STEEL PVT. -

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for All People Groups & LR-Unreached People Groups = LR-Upgs

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & LR-Unreached People Groups = LR-UPGs - of INDIA Source: Joshua Project data, www.joshuaproject.net Western edition To order prayer resources or for inquiries, contact email: [email protected] I give credit & thanks to Create International for permission to use their PG photos. 2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & LR-UPGs = Least-Reached-Unreached People Groups of India INDIA SUMMARY: 2,717 total People Groups; 2,445 LR-UPG India has 1/3 of all UPGs in the world; the most of any country LR-UPG definition: 2% or less Evangelical & 5% or less Christian Frontier (FR) definition: 0% to 0.1% Christian Why pray--God loves lost: world UPGs = 7,407; Frontier = 5,042. Color code: green = begin new area; blue = begin new country Downloaded from www.joshuaproject.net in September 2020 * * * "Prayer is not the only thing we can can do, but it is the most important thing we can do!" * * * India ISO codes are used for some Indian states as follows: AN = Andeman & Nicobar. JH = Jharkhand OD = Odisha AP = Andhra Pradesh+Telangana JK = Jammu & Kashmir PB = Punjab AR = Arunachal Pradesh KA = Karnataka RJ = Rajasthan AS = Assam KL = Kerala SK = Sikkim BR = Bihar ML = Meghalaya TN = Tamil Nadu CT = Chhattisgarh MH = Maharashtra TR = Tripura DL = Delhi MN = Manipur UT = Uttarakhand GJ = Gujarat MP = Madhya Pradesh UP = Uttar Pradesh HP = Himachal Pradesh MZ = Mizoram WB = West Bengal HR = Haryana NL = Nagaland Why Should We Pray For Unreached People Groups? * Missions & salvation of all people is God's plan, God's will, God's heart, God's dream, Gen.