Social Differentiation and Age-Friendly Characteristics : a Case Study in Tuen Mun

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Recognized Villages Under the New Territories Small House Policy

LIST OF RECOGNIZED VILLAGES UNDER THE NEW TERRITORIES SMALL HOUSE POLICY Islands North Sai Kung Sha Tin Tuen Mun Tai Po Tsuen Wan Kwai Tsing Yuen Long Village Improvement Section Lands Department September 2009 Edition 1 RECOGNIZED VILLAGES IN ISLANDS DISTRICT Village Name District 1 KO LONG LAMMA NORTH 2 LO TIK WAN LAMMA NORTH 3 PAK KOK KAU TSUEN LAMMA NORTH 4 PAK KOK SAN TSUEN LAMMA NORTH 5 SHA PO LAMMA NORTH 6 TAI PENG LAMMA NORTH 7 TAI WAN KAU TSUEN LAMMA NORTH 8 TAI WAN SAN TSUEN LAMMA NORTH 9 TAI YUEN LAMMA NORTH 10 WANG LONG LAMMA NORTH 11 YUNG SHUE LONG LAMMA NORTH 12 YUNG SHUE WAN LAMMA NORTH 13 LO SO SHING LAMMA SOUTH 14 LUK CHAU LAMMA SOUTH 15 MO TAT LAMMA SOUTH 16 MO TAT WAN LAMMA SOUTH 17 PO TOI LAMMA SOUTH 18 SOK KWU WAN LAMMA SOUTH 19 TUNG O LAMMA SOUTH 20 YUNG SHUE HA LAMMA SOUTH 21 CHUNG HAU MUI WO 2 22 LUK TEI TONG MUI WO 23 MAN KOK TSUI MUI WO 24 MANG TONG MUI WO 25 MUI WO KAU TSUEN MUI WO 26 NGAU KWU LONG MUI WO 27 PAK MONG MUI WO 28 PAK NGAN HEUNG MUI WO 29 TAI HO MUI WO 30 TAI TEI TONG MUI WO 31 TUNG WAN TAU MUI WO 32 WONG FUNG TIN MUI WO 33 CHEUNG SHA LOWER VILLAGE SOUTH LANTAU 34 CHEUNG SHA UPPER VILLAGE SOUTH LANTAU 35 HAM TIN SOUTH LANTAU 36 LO UK SOUTH LANTAU 37 MONG TUNG WAN SOUTH LANTAU 38 PUI O KAU TSUEN (LO WAI) SOUTH LANTAU 39 PUI O SAN TSUEN (SAN WAI) SOUTH LANTAU 40 SHAN SHEK WAN SOUTH LANTAU 41 SHAP LONG SOUTH LANTAU 42 SHUI HAU SOUTH LANTAU 43 SIU A CHAU SOUTH LANTAU 44 TAI A CHAU SOUTH LANTAU 3 45 TAI LONG SOUTH LANTAU 46 TONG FUK SOUTH LANTAU 47 FAN LAU TAI O 48 KEUNG SHAN, LOWER TAI O 49 KEUNG SHAN, -

M / SP / 14 / 172 ¨·P Eªä 13 Yeung Siu Hang Century M �⁄ Gateway a PUI to ROAD C S· L E S·O 11 H

·‘†Łƒ C«s¤ Close Quarter Battle Range ¶¶· Sun Fung Wai l¹º Yonking Garden dª ⁄l s•‹Łƒ KONG SHAM Nai Wai Qª Tuen Tsz Wai West N.T. Landfill 100 Chung Shan C«j A´ Z¸W Tsing Chuen Wai CASTLE PEAK ROAD - LAM TEI The Sherwood g 200 HIGHWAY j⁄ ROAD Tai Shui Hang I´A¿ WESTERN ⁄l Fortress Garden LONG WAN Tuen Tsz Wai flA» ø¨d NIM Ø Villa Pinada ROAD Dumping Area Å LAU Tsoi Yuen Tsuen YUEN HIGHWAY NG Lam Tei Light Rail 200 297 q a Å AD ®§k RO w Z¸ œf Miu Fat ¿´ ”ºƒ 80 Lingrade Monastery TSUI Nim Wan Garden The Sherwood g Ser Res ´» ½ õ«d Borrow Area s TSANG ÅÂa¦ C y s LAM TEI ¤h HO N d±_ G P s·y C«s¤m½v O ⁄ø“ RO MAIN A San Hing Tsuen STREET D Tuen Mun ¿´ San Tsuen Tsang Tsui SAN HING ”º æ” Fuk Hang Tsuen RO AD Botania Villa ”ºƒ 300 FUK HANG _˜ TSUEN ROAD — RD 67 Pipeline 300 Po Tong Ha Tsz Tin Tsuen 100 LAU fiØ To Yuen Wai NG 69 394 65 ‚⁄fi 100 300 200 29 ƒŒ — Lo Fu Hang ¥d ROAD SIU HONG RD NULLAH C«s¤m½v TSZ HANG 200 FU NIM WAN ROAD TIN êªa¦ RD Tsing Shan Firing Range Boundary p¤| ê| Fu Tei Ha Tsuen Siu Hang Tsuen ¥d 30 ¥q 100 TONG HANG RD LINGNAN Z¸W 100 _˜ I´õ 45 Fu Tai Estate Quarry 200 IJT - _˜ 66 ⁄Q 68 IJG TSING LUN ROAD qÄs 47 RD 31 Kwong Shan Tsuen HUNG SHUI HANG Q˜ KWAI 44 TUEN SIU HONG RESERVOIR E»d± HING FU STREET 64 BeneVille ¶º TUEN QÄC ST FU RD 27 Catchwater TSING ROAD PEAK CASTLE ¥ Tsing Shan Firing Range Boundary Siu Hong KEI Pipeline 281 Court 46 200 _ÄÐ HING KWAI ST Œœ 100 32 M²D² Parkland Villas ⁄I 61 63 Ching Leung SAN FUK RD Nunnery LAM TEI RESERVOIR C«s¤ TUEN MUN ROAD s• ›n« Castle Peak Hospital TUEN FU RD 137 33 Lingnan -

New Territories

Branch ATM District Branch / ATM Address Voice Navigation ATM 1009 Kwai Chung Road, Kwai Chung, New Kwai Chung Road Branch P P Territories 7-11 Shek Yi Road, Sheung Kwai Chung, New Sheung Kwai Chung Branch P P P Territories 192-194 Hing Fong Road, Kwai Chung, New Ha Kwai Chung Branch P P P Territories Shop 102, G/F Commercial Centre No.1, Cheung Hong Estate Commercial Cheung Hong Estate, 12 Ching Hong Road, P P P P Centre Branch Tsing Yi, New Territories A18-20, G/F Kwai Chung Plaza, 7-11 Kwai Foo Kwai Chung Plaza Branch P P Road, Kwai Chung, New Territories Shop No. 114D, G/F, Cheung Fat Plaza, Cheung Fat Estate Branch P P P P Cheung Fat Estate, Tsing Yi, New Territories Shop 260-265, Metroplaza, 223 Hing Fong Metroplaza Branch P P Road, Kwai Chung, New Territories 40 Kwai Cheong Road, Kwai Chung, New Kwai Cheong Road Branch P P P P Territories Shop 115, Maritime Square, Tsing Yi Island, Maritime Square Branch P P New Territories Maritime Square Wealth Management Shop 309A-B, Level 3, Maritime Square, Tsing P P P Centre Yi, New Territories ATM No.1 at Open Space Opposite to Shop No.114, LG1, Multi-storey Commercial /Car Shek Yam Shopping Centre Park Accommodation(also known as Shek Yam Shopping Centre), Shek Yam Estate, 120 Lei Muk Road, Kwai Chung, New Territories. Shop No.202, 2/F, Cheung Hong Shopping Cheung Hong Estate Centre No.2, Cheung Hong Estate, 12 Ching P Hong Road, Tsing Yi, New Territories Shop No. -

Student Services Centre July 2017 Contents

Handbook For Non-local Degree-seeking Students Student Services Centre July 2017 Contents 1. PLANNING YOUR ARRIVAL P2 1.1 Important Dates 1.2 Things To Bring Along 1.3 Arrival Pick-up Service 2. Arrival and Orientation P5 2.1 Reporting and Hostel Check-in 2.2 Orientation 3. STUDYING AT LINGNAN P8 3.1 Course Registration 3.2 Graduation Requirements 3.3 Academic Support Services 4. FACILITIES AND STUDENT SERVICES P13 Facilities 4.1 Student Hostels 4.2 Dining Facilities 4.3 Sports Facilities 4.4 Chaplain’s Office 4.5 Prayer/ Meditation Room Student Services 4.6 Healthcare 4.7 Lingnan Host Family Scheme 4.8 Student Societies/ University Teams 4.9 Student Development Awards 5. FINANCIAL MATTERS P20 5.1 Bank Account, Automated Teller Machine and Credit Card 5.2 Expenses 5.3 Octopus Card 5.4 MTR Student Travel Scheme 6. LIVING IN HONG KONG P22 6.1 Hong Kong Identity Card 6.2 Internship / Part-time job 6.3 Weather and Clothing 6.4 Communication 7. COPING WITH A NEW CULTURE P26 7.1 Culture Shock 7.2 How do I Adjust and Cope with a New Culture 7.3 Tips on Adjustment from Senior Non-local Degree-seeking Students 8. APPENDICES P31 Appendix 1 Contacts of University Units/ Campus Facilities Appendix 2 Useful Contacts in Hong Kong Appendix 3.1 Transportation from Shen Zhen Airport / Lo Wu Railway Station to Lingnan University Appendix 3.2 Transportation from Hong Kong International Airport to Lingnan University Appendix 4 Mass Transit Railway (MTR) Route Map Appendix 5 Campus Map P1 Planning Your Arrival 1.1 Important Dates In each academic year, there are three Terms: Term 1, Term 2 and Summer Term. -

Agenda of the 1 Meeting of the District Facilities Management Committee

Agenda of the 1st Meeting of the District Facilities Management Committee Tuen Mun District Council (2020 – 2021) Date : 25 February 2020 (Tuesday) Time : 9:30 a.m. Venue : Tuen Mun District Council (TMDC) Conference Room, 3/F, Tuen Mun Government Offices, 1 Tuen Hi Road, Tuen Mun Agenda I. Discussion Items A. Terms of Reference for the District Facilities Management Committee (2020-2021) (DFMC Paper No. 1/2020) B. Formation of Working Groups under the District Facilities Management Committee (2020-2021) (DFMC Paper No. 2/2020) C. The Arrangement of New Works Proposals (DFMC Paper No. 3/2020) D. LCSD’s Recreational and Sports Activities Plan for Tuen Mun District from April 2020 to March 2021 (DFMC Paper No. 4/2020) E. LCSD’s Trial on the Use of Cheerleading Items for Hong Kong Premier League at Tuen Mun Tang Shiu Kin Sports Ground (DFMC Paper No. 5/2020) F. Proposal on LCSD’s Free Cultural Programmes in Tuen Mun District (2020-21) (DFMC Paper No. 6/2020) G. Adjustment to or Cancellation of Existing Smoking Areas in Tuen Mun Park (DFMC Paper No. 7/2020) H. Concern over Noise and Management Problems of Tuen Mun Park and Request for Enhanced Regulation of Unauthorised Music/Dance Performances (DFMC Paper No. 8/2020) I. Request Planning Department to Report Immediately on Detailed Planning Arrangements for Community Facilities Currently Lacking in Tuen Mun (DFMC Paper No. 9/2020) J. Follow Up on Works Concerning Sports Ground in Area 16 and Tuen Mun South Extension (DFMC Paper No. 10/2020) K. Request for Addition of Shelter to the Walkway between Tuen Kwai Road and Siu Hong West Rail Station (DFMC Paper No. -

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL PANEL on TRANSPORT Progress Update on the Installation of Speed Enforcement Camera and Red Light Camera

CB(1)477/03-04(02) LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL PANEL ON TRANSPORT Progress Update on the Installation of Speed Enforcement Camera and Red Light Camera Systems Introduction This paper updates Members on the progress of the installation of speed enforcement camera and red light camera systems. Background Speed Enforcement Cameras 2. Driving in excess of speed limits on the road has contributed to the occurrence and severity of most traffic accidents. Overseas experience shows that installation of speed enforcement cameras (SECs) at strategic locations is a useful means to combat speeding effectively. 3. Before January 1999, there were only 10 locations along Tolo Highway and Fanling Highway that were installed with SEC on- site equipment. In January 1999, we consulted this Panel on our proposal to expand the coverage of SECs to 60 other locations at strategic roads and expressways, and to place eight cameras at these locations on a rotational basis. The funding requirement for the procurement of cameras and computer systems, installation works, testing of equipment and contingencies was estimated to be $25.16m. Members supported the proposal. We subsequently secured the Finance Committee (FC)’s funding approval for the project in July 1999. However, as the price of the successful bid was lower than our estimate, we decided to add another 15 locations to the project, then making a total of 75 locations. The project was scheduled to be completed by September 2002. The list of locations is at Annex A. - 2 - Red Light Cameras 4. The red light camera (RLC) system aims to deter drivers from red light jumping which accounts for more than 80% of traffic signal offences. -

Review of Operations

Review of Operations 21 Property Sales 64 Property Related Businesses 22 Hong Kong Property Business 71 Telecommunications and Information Technology 22 Land Bank 72 Transportation, Infrastructure and Logistics 24 Property Development 34 Property Investment 75 Corporate Finance 44 Mainland Property Business 76 Customer Service 44 Land Bank 46 Property Development 60 Property Investment The Group’s International Commerce Centre and International Finance Centre form a magnificent Victoria Harbour Gateway SUN HUNG KAI PROPERTIES LIMITED 20 Annual Report 2009/10 Property Sales The Group sold or pre-sold an attributable HK$23,218 million worth of properties in the third quarter of 2010, mainly from Hong Kong of properties in the year under review, compared to last year’s properties including Lime Stardom in Kowloon and Larvotto in HK$25,674 million. A number of projects in Hong Kong and on the Island South. Nearly 95 per cent of the units in these two projects mainland were put on the market over the past year and produced have been sold. highly encouraging sales. The Group will continue offering new developments for sale as Sales of Hong Kong properties amounted to HK$20,562 million, planned. Major residential projects in Hong Kong to go on sale in mostly from YOHO Midtown in Yuen Long, Aria and The Latitude the rest of the current financial year include luxury town houses in Kowloon and The Cullinan at Kowloon Station. The remaining Valais at Beas River, Avignon on Castle Peak Road, Park Nara and a HK$2,656 million was from mainland and Singapore properties, project on Po Yip Street in Yuen Long and the residential towers including Lake Dragon in Guangzhou and Orchard Residences in at the integrated landmark development at Tseung Kwan O Singapore. -

Fare Table for KMB Bus Routes Effective Date: 17 Mar 2013 Route No

Page 1 Fare Table For KMB Bus Routes Effective Date: 17 Mar 2013 Route No. Route Fare 1 Star Ferry Chuk Yuen Estate $5.50 Nathan Road to Star Ferry $4.90 Mong Kok Road to Chuk Yuen Estate $5.10 1A Star Ferry Sau Mau Ping (Central) $6.90 Kwun Tong (Yue Man Square) to Star Ferry $6.60 Prince Edward Road East(San Po Kong) to Star Ferry $5.50 Nathan Road to Star Ferry $4.90 Mong Kok Road to Sau Mau Ping (Central) $6.60 Kwun Tong Road (Lower Ngau Tau Kok Estate) to Sau Mau Ping (Central) $5.50 Kwun Tong Road (Yue Man Square) to Sau Mau Ping (Central) $4.30 2 Star Ferry So Uk $4.70 2A Mei Foo Lok Wah $5.50 Ngau Tau Kok Road to Lok Wah $4.90 Lai Chi Kok Road / Nathan Road Junction to Mei Foo $4.90 2B Chuk Yuen Estate Cheung Sha Wan $4.70 2C Yau Yat Tsuen Tsim Sha Tsui [Circular] $4.70 2D Tung Tau Estate Chak On Estate $4.70 2E Kowloon City Ferry Pak Tin $4.90 2F Cheung Sha Wan Tsz Wan Shan(NoRouteh) $5.50 Wong Tai Sin Station to Tsz Wan Shan (NoRouteh) $4.90 3B Hung Hom Ferry Concourse Tsz Wan Shan (Central) $4.90 3C China Ferry Terminal Tsz Wan Shan (NoRouteh) $5.50 Nathan Road to China Ferry Terminal $4.90 Argyle Street to Tsz Wan Shan (NoRouteh) $5.10 Wong Tai Sin Station to Tsz Wan Shan (NoRouteh) $4.90 3D Kwun Tong (Yue Man Square) Tsz Wan Shan (Central) $4.90 3M Tsz Wan Shan (NoRouteh) Choi Wan $4.10 Clear Water Bay Road (outside Choi Hung Station) to Choi Wan $3.70 3P#◇▽ Tsz Wan Shan (South) Choi Wan $4.10 Clear Water Bay Road (Choi Hung Station) to Choi Wan $3.70 3S ◎ Diamond Hill Station Diamond Hill Cemetery [Circular] -

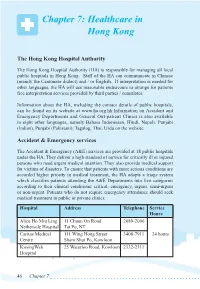

Chapter 7: Healthcare in Hong Kong

Chapter 7: Healthcare in Hong Kong The Hong Kong Hospital Authority The Hong Kong Hospital Authority (HA) is responsible for managing all local public hospitals in Hong Kong. Staff of the HA can communicate in Chinese (mainly the Cantonese dialect) and / or English. If interpretation is needed for other languages, the HA will use reasonable endeavours to arrange for patients free interpretation services provided by third parties / consulates. Information about the HA, including the contact details of public hospitals, can be found on its website at www.ha.org.hk.Information on Accident and Emergency Departments and General Out-patient Clinics is also available in eight other languages, namely Bahasa Indonesian, Hindi, Nepali, Punjabi (Indian), Punjabi (Pakistani), Tagalog, Thai, Urdu on the website. Accident & Emergency services The Accident & Emergency (A&E) services are provided at 18 public hospitals under the HA. They deliver a high standard of service for critically ill or injured persons who need urgent medical attention. They also provide medical support for victims of disasters. To ensure that patients with more serious conditions are accorded higher priority in medical treatment, the HA adopts a triage system which classifies patients attending the A&E Departments into five categories according to their clinical conditions: critical, emergency, urgent, semi-urgent or non-urgent. Patients who do not require emergency attendance should seek medical treatment in public or private clinics. Hospital Address Telephone Service Hours Alice Ho Miu Ling 11 Chuen On Road 2689-2000 Nethersole Hospital Tai Po, NT Caritas Medical 111 Wing Hong Street 3408-7911 24 hours Centre Sham Shui Po, Kowloon KwongWah 25 Waterloo Road, Kowloon 2332-2311 Hospital 46 Chapter 7 North District 9 Po Kin Road 2683-8888 Hospital Sheung Shui, NT North Lantau 1/F, 8 Chung Yan Road 3467-7000 Hospital Tung Chung, Lantau, N.T. -

Master of Science in Marketing and International Business

Master of Science in Marketing and International Business STUDENT HANDBOOK 2020/21 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. About Lingnan University ...............................................................................................7 1.1 Vision, Mission and Core Values ...................................................................................8 1.2 Graduate Attributes for Taught Postgraduate (TPg) Programmes .............................9 2 Programme Information .............................................................................................. 10 2.1 Background .................................................................................................................. 10 2.2 Aims and Learning Goals ............................................................................................ 10 2.3 Entrance Requirements .............................................................................................. 11 2.4 Mode of Study ............................................................................................................. 11 2.5 Normal and Maximum Duration of Study .................................................................. 11 2.6 Medium of Instruction ................................................................................................. 11 2.7 Contributing Departments /Units/External Partners ................................................. 11 2.8 Programme Structure .................................................................................................. 12 2.8.1 Curriculum..................................................................................................... -

List of Medical Social Services Units Under Social Welfare Department

List of Medical Social Services Units Under Social Welfare Department Hong Kong Name of Hospital/Clinic Tel. No. Email Address 1. Queen Mary Hospital 2255 3762 [email protected] 2255 3764 2. Wong Chuk Hang Hospital 2873 7201 [email protected] 3. Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern 2595 6262 [email protected] Hospital 4. Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern 2595 6773 [email protected] Hospital (Psychiatric Department) Kowloon Name of Hospital/Clinic Tel. No. Email Address 5. Tseung Kwan O Hospital 2208 0335 [email protected] 2208 0327 6. United Christian Hospital 3949 5178 [email protected] (Psychiatry) 7. Queen Elizabeth Hospital 3506 7021 [email protected] 3506 7027 3506 5499 3506 4021 8. Hong Kong Eye Hospital 2762 3069 [email protected] 9. Kowloon Hospital Rehabilitation 3129 7857 [email protected] Building 10. Kowloon Hospital 3129 6193 [email protected] 11. Kowloon Hospital 2768 8534 [email protected] (Psychiatric Department) 1 The New Territories Name of Hospital/Clinic Tel. No. Email Address 12. Prince of Wales Hospital 3505 2400 [email protected] 13. Shatin Hospital 3919 7521 [email protected] 14. Tai Po Hospital 2607 6304 [email protected] Sub-office Tai Po Hospital (Child and Adolescent 2689 2486 [email protected] Mental Health Centre) 15. North District Hospital 2683 7750 [email protected] 16. Tin Shui Wai Hospital 3513 5391 [email protected] 17. Castle Peak Hospital 2456 7401 [email protected] 18. Siu Lam Hospital 2456 7186 [email protected] 19. -

Hospital Authority's Planned Projects for 2021-2022

LC Paper No. CB(4)503/20-21(02) Head 708 Subhead 8083MM One-Off Grant to the Hospital Authority for Minor Works Projects 2021-22 Planned Projects Prepared by the Hospital Authority February 2021 Head 708 : Subhead 8083MM One-off Grant to the Hospital Authority for Minor Works Projects for the 2019-20 Financial Year Part A - Previously approved items and other items to commence in 2020-21 with expected expenditure in 2020-21 and/or 2021-22 Actual Approved Cumulative Revised Estimated cash flow in subsequent years Expenditure Estimate Priority / Project Expenditure Estimate Project Title (1.4.2020 to 2021-22 Post Item No. Estimate to 31.3.2020 2020-21 31.10.2020) 2022-23 2023-24 2024-25 2024-25 ($'000) (I) Previously approved items (up to 31.10.2020) with expected expenditure in 2020-21 and/or 2021-22 EMR15-604 Modernisation of lifts in Day Treatment Block and Special Block in Prince of Wales Hospital 16,794 16,540 254 254 - - - - - EMR16-104 Replacement of the local central control and monitoring system for Wong Chuk Hang Hospital 1,280 1,150 39 101 - 30 - - - EMR16-401 Replacement of fire alarm and detection system at Hospital Main Block in Tseung Kwan O 6,500 6,500 (1,371) (1,371) - - - - - Hospital EMR16-504 Replacement of 1 no. main switch board for Block A in Yan Chai Hospital 2,345 2,202 142 142 - - - - - EMR16-505 Replacement of building management system at Multi Services Complex in Yan Chai Hospital 3,500 3,148 55 55 297 - - - - EMR16-506 Replacement of the air handling unit for Department of Central Supporting Services at 1/F, 502 526 (24) (24) - - - - - Block B in Yan Chai Hospital EMR17-102 Replacement of emergency generators for Hospital Block at St.