60 Years of Driving Growth to Every Corner of Philadelphia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic Philadelphia, Inc. 2012 Fall Programming Fact Sheet

PRESS CONTACT: Cari Feiler Bender, Relief Communications, LLC (610) 416-1216, [email protected] HISTORIC PHILADELPHIA, INC. 2012 FALL PROGRAMMING FACT SHEET DESCRIPTION: Historic Philadelphia, Inc. makes our nation’s history relevant and real through interpretation, interaction, and education, strengthening Greater Philadelphia’s role as the destination to experience American history. Historic Philadelphia, Inc.’s Once Upon A Nation brings history to life, featuring Adventure Tours (walking tours), History Makers, Storytelling Benches throughout the Historic District and at Valley Forge, and the Benstitute to specially train all staff. Franklin Square is an outdoor amusement oasis with Philadelphia-themed Mini Golf, the Philadelphia Park Liberty Carousel, and SquareBurger, hosting parties and special events in the new Pavilion in Franklin Square. Liberty 360 , a digital 3-D experience, is a year-round indoor attraction housed at the Historic Philadelphia Center as Phase I of the all-new completely re-imagined Lights of Liberty . The Betsy Ross House allows visitors a personal look at the story and home of a famous historical figure, with newly remodeled and reinterpreted rooms and changing exhibitions. LIBERTY 360: Liberty 360 in the PECO Theater immerses the viewer in the symbols of freedom. Benjamin Franklin appears in a groundbreaking 360-degree, 3-D show unlike anything that has ever been seen before, and escorts the audience on a journey of discovery and exploration of America’s most beloved symbols. The 15-minute, 3-D film surrounds -

The Battles of Germantown: Public History and Preservation in America’S Most Historic Neighborhood During the Twentieth Century

The Battles of Germantown: Public History and Preservation in America’s Most Historic Neighborhood During the Twentieth Century Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By David W. Young Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Steven Conn, Advisor Saul Cornell David Steigerwald Copyright by David W. Young 2009 Abstract This dissertation examines how public history and historic preservation have changed during the twentieth century by examining the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Founded in 1683, Germantown is one of America’s most historic neighborhoods, with resonant landmarks related to the nation’s political, military, industrial, and cultural history. Efforts to preserve the historic sites of the neighborhood have resulted in the presence of fourteen historic sites and house museums, including sites owned by the National Park Service, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and the City of Philadelphia. Germantown is also a neighborhood where many of the ills that came to beset many American cities in the twentieth century are easy to spot. The 2000 census showed that one quarter of its citizens live at or below the poverty line. Germantown High School recently made national headlines when students there attacked a popular teacher, causing severe injuries. Many businesses and landmark buildings now stand shuttered in community that no longer can draw on the manufacturing or retail economy it once did. Germantown’s twentieth century has seen remarkably creative approaches to contemporary problems using historic preservation at their core. -

0511House-Urban Affairsmichelle

1 1 COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 2 URBAN AFFAIRS COMMITTEE 3 COATESVILLE CITY HALL, COUNCIL CHAMBERS 4 WEDNESDAY, MAY 11, 2016 5 10:00 A.M. 6 PUBLIC HEARING ON BLIGHT 7 8 BEFORE: HONORABLE SCOTT A. PETRI, MAJORITY CHAIR HONORABLE BECKY CORBIN 9 HONORABLE JERRY KNOWLES HONORABLE HARRY LEWIS 10 HONORABLE JAMES R. SANTORA HONORABLE ED NEILSON 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 2 1 COMMITTEE STAFF PRESENT CHRISTINE GOLDBECK 2 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, HOUSE URBAN AFFAIRS COMMITTEE 3 V. KURT BELLMAN 4 RESEARCH ANALYST, DEMOCRATIC COMMITTEE 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 3 1 I N D E X 2 OPENING REMARKS By Chairman Petri 5 - 6 3 By Representative Santora 6 By Representative Knowles 6 - 7 4 By Representative Nielson 7 - 8 5 REMARKS By Chairman Petri 8 - 10 6 OPENING REMARKS 7 By Representative Corbin 10 - 11 By Representative Lewis 11 - 14 8 By Linda Lavender Norris 14 9 DISCUSSION AMONG PARTIES 15 - 19 10 PRESENTATION By Dave Sciocchetti 19 - 22 11 QUESTIONS FROM COMMITTEE MEMBERS 23 - 28 12 PRESENTATION 13 By Michael Trio 28 - 38 By Sonia Huntzinger 38 - 42 14 QUESTIONS FROM COMMITTEE MEMBERS 42 - 59 15 PRESENTATION 16 By Joshua Young 59 - 65 By Kristin Camp 65 - 70 17 QUESTIONS FROM COMMITTEE MEMBERS 70 - 77 18 PRESENTATION 19 By Jack Assetto 78 - 81 By James Thomas 81 - 85 20 QUESTIONS FROM COMMITTEE MEMBERS 85 - 89 21 PRESENTATION 22 By Dr. -

TUESDAY, M Y 1, 1962 the President Met with the Following of The

TUESDAY, MAYMYI,1, 1962 9:459:45 -- 9:50 am The PrePresidentsident met with the following of the Worcester Junior Chamber of CommeCommerce,rce, MasMassachusettssachusetts in the Rose Garden: Don Cookson JJamesarne s Oulighan Larry Samberg JeffreyJeffrey Richard JohnJohn Klunk KennethKenneth ScScottott GeorgeGeorge Donatello EdwardEdward JaffeJaffe RichardRichard MulhernMulhern DanielDaniel MiduszenskiMiduszenski StazrosStazros GaniaGaniass LouiLouiss EdmondEdmond TheyThey werewere accorrpaccompaniedanied by CongresCongressmansman HaroldHarold D.D. DonohueDonohue - TUESDAY,TUESbAY J MAY 1, 1962 8:45 atn LEGISLATIVELEGI~LATIVE LEADERS BREAKFAST The{['he Vice President Speaker John W. McCormackMcCortnack Senator Mike Mansfield SenatorSenato r HubertHube rt HumphreyHUInphrey Senator George SmatherStnathers s CongressmanCongresstnan Carl Albert CongressmanCongresstnan Hale BoggBoggs s Hon. Lawrence O'Brien Hon. Kenneth O'Donnell0 'Donnell Hon. Pierre Salinger Hon. Theodore Sorensen 9:35 amatn The President arrived in the office. (See insert opposite page) 10:32 - 10:55 amatn The President mettnet with a delegation fromfrotn tktre Friends'Friends I "Witness for World Order": Henry J. Cadbury, Haverford, Pa. Founder of the AmericanAtnerican Friends Service CommitteeCOtntnittee ( David Hartsough, Glen Mills, Pennsylvania Senior at Howard University Mrs. Dorothy Hutchinson, Jenkintown, Pa. Opening speaker, the Friends WitnessWitnes~ for World Order Mr. Samuel Levering, Arararat, Virginia Chairman of the Board on Peace and.and .... Social Concerns Edward F. Snyder, College Park, Md. Executive Secretary of the Friends Committe on National Legislation George Willoughby, Blackwood Terrace, N. J. Member of the crew of the Golden Rule (ship) and the San Francisco to Moscow Peace Walk (Hon. McGeorgeMkGeorge Bundy) (General Chester V. Clifton 10:57 - 11:02 am (Congre(Congresswomansswoman Edith Green, Oregon) OFF TRECO 11:15 - 11:58 am H. -

Wells Fargo Center Suite Menu.Pdf

Packages The Bella Vista 525/550 Event Day PACKAGES SERVE APPROXIMATELY 12 GUESTS FEDERAL PRETZELS Philadelphia Classic Sea Salt Soft Pretzels, Spicy Mustard (350 cal per Pretzel) (10 cal per 2 oz Spicy Mustard) POPCORN gf Enhance Your Experience Bottomless Fresh Popped, Souvenir Pail (190 cal per 1 oz serving) To further enhance your experience add one of our other menu favorites. ® UTZ WAVY POTATO CHIPS gf CHICKIE’S & PETE’S ® WORLD FAMOUS Onion Dip ® (280 cal per 1.8 oz Wavy Potato Chips) (150 cal per 1.3 oz Onion Dip) CRAB FRIES gf 54 Cheese Sauce CHICKIE’S & PETE’S ® CUTLETS (1140 cal per 13.3 oz Fries) (130 cal per 2.7 oz Cheese Sauce) Two orders of the World Famous Cutlets, with Honey Mustard & BBQ (1170 cal per 13.4 oz Cutlet) (230 calories per 1.7 oz Honey Mustard) (90 cal per 1.7 oz BBQ) FARMERS’ MARKET SEASONAL CRUDITÉ gf 54 Carrots, Peppers, English Cucumbers, Broccoli, Ranch Dressing SMOKED TURKEY HOAGIE (110 cal per 5.2 oz Vegetables) (80 cal per.85 oz Ranch Dressing) House Smoked Turkey, Herb Cheese Spread, Bacon, Roasted Red Pepper, Arugula, Amoroso ® Seeded Roll (410 cal 9.66 oz Smoked Turkey Hoagie) BEVERAGE PACKAGE #1 170 1 Six-Pack Each of Pepsi, Diet Pepsi, Sierra Mist, PHILLY CHEESESTEAKS Bottled Water and 3 Six-Packs of Domestic Beer of Your Choice “Wit” Sautéed Onions, Cheese Sauce, Amoroso ® Roll (570 cal per 12.31 oz Philly Cheesesteak) SERVES 6 DIETZ & WATSON ® GRILLED ARENA HOT DOGS All Beef Hot Dogs, Sauerkraut, Potato Buns (350 cal per 4.48 oz Hot Dog) (5 cal per oz 1.34 Sauerkraut) (150 cal 1.87 per oz Potato Bun) The calorie and nutrition information provided is for individual servings , FRESH BAKED COOKIES not for the total number of servings on each tray, because serving Chef’s Choice of Fresh Baked Cookies styles e.g. -

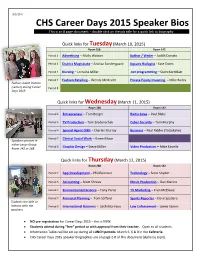

CHS Career Days 2015 Speaker Bios This Is an 8 Page Document – Double Click on the Job Title for a Quick Link to Biography

3/3/15 C CHS Career Days 2015 Speaker Bios This is an 8 page document – double click on the job title for a quick link to biography. Quick links for Tuesday (March 10, 2015) Room 268 Room 142 Period 2 Advertising – Molly Watson Author / Writer – Judith Donato Period 3 District Magistrate – Analisa Sondergaard Aquatic Biologist - Kate Doms Period 4 Nursing – Lorraine Miller .net programming – Scott Kornblatt Period 7 Fashion Retailing – Wendy McDevitt Private Equity Investing – Mike Bailey Author, Judith Donato (center) during Career Period 8 Days 2013 Quick links for Wednesday (March 11, 2015) Room 268 Room 142 Period 2 Entrepreneur – Tom Borger Radio Sales – Paul Blake Period 3 TV Production – Tom Sredenschek Cyber Security – Tom Murphy Period 4 Special Agent (FBI) – Charles Murray Business – Paul Ridder (Tastykake) Period 7 Clinical Social Work – Karen Moon Speakers present in either Large Group Period 8 Graphic Design – Steve Miller Video Production – Mike Fanelle Room 142 or 268. Quick links for Thursday (March 12, 2015) Room 268 Room 142 Period 2 App Development – Phil Reitnour Technology – Scott Snyder Period 3 Accounting – Scott Shreve Music Production – Dan Marino Period 4 Environmental Science – Tony Parisi TV Marketing – Fran McElwee Period 7 Financial Planning – Tom Safford Sports Reporter – Dave Spadaro Students are able to interact with the Period 8 International Business – Seth Morrison Law Enforcement – Jamie Kemm speakers. NO pre-registration for Career Days 2015 – this is NEW. Students attend during “free” period or with approval from their teacher. Open to all students. Information Tables will be set up during all LUNCH periods: March 5, 6 & 9 in the Cafeteria CHS Career Days 2015 speaker biographies are on page 2-8 of this document (alpha by topic). -

IV. Fabric Summary 282 Copyrighted Material

Eastern State Penitentiary HSR: IV. Fabric Summary 282 IV. FABRIC SUMMARY: CONSTRUCTION, ALTERATIONS, AND USES OF SPACE (for documentation, see Appendices A and B, by date, and C, by location) Jeffrey A. Cohen § A. Front Building (figs. C3.1 - C3.19) Work began in the 1823 building season, following the commencement of the perimeter walls and preceding that of the cellblocks. In August 1824 all the active stonecutters were employed cutting stones for the front building, though others were idled by a shortage of stone. Twenty-foot walls to the north were added in the 1826 season bounding the warden's yard and the keepers' yard. Construction of the center, the first three wings, the front building and the perimeter walls were largely complete when the building commissioners turned the building over to the Board of Inspectors in July 1829. The half of the building east of the gateway held the residential apartments of the warden. The west side initially had the kitchen, bakery, and other service functions in the basement, apartments for the keepers and a corner meeting room for the inspectors on the main floor, and infirmary rooms on the upper story. The latter were used at first, but in September 1831 the physician criticized their distant location and lack of effective separation, preferring that certain cells in each block be set aside for the sick. By the time Demetz and Blouet visited, about 1836, ill prisoners were separated rather than being placed in a common infirmary, and plans were afoot for a group of cells for the sick, with doors left ajar like others. -

Journal of Urban History

Journal of Urban History http://juh.sagepub.com/ ''From Protest to Politics'' : Community Control and Black Independent Politics in Philadelphia, 1965-1984 Matthew J. Countryman Journal of Urban History 2006 32: 813 DOI: 10.1177/0096144206289034 The online version of this article can be found at: http://juh.sagepub.com/content/32/6/813 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: The Urban History Association Additional services and information for Journal of Urban History can be found at: Email Alerts: http://juh.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://juh.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://juh.sagepub.com/content/32/6/813.refs.html Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at Harvard Libraries on March 22, 2011 “FROM PROTEST TO POLITICS” Community Control and Black Independent Politics in Philadelphia, 1965-1984 MATTHEW J. COUNTRYMAN University of Michigan This article traces the origins of black independent electoral activism in Philadelphia during the 1970s to the Black Power movement of the 1960s. Specifically, it argues that Black Power activists in Philadelphia turned to electoral strategies to consolidate their efforts to achieve community control over public insti- tutions in the city’s black working-class neighborhoods. Finally, the article concludes with a brief evalu- ation of the careers of African American activist state legislators David Richardson and Roxanne Jones and W. Wilson Goode, Philadelphia’s first African American mayor. Keywords: Black Power; community control; independent politics; Democratic Party The political philosophy of black nationalism means that the black man should control the politics and politicians in his own community. -

Re-Evaluating the Design of the Richardson Dilworth House

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2013 Go with the Faux: Re-Evaluating the Design of the Richardson Dilworth House Chelsea Elizabeth Troppauer University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Troppauer, Chelsea Elizabeth, "Go with the Faux: Re-Evaluating the Design of the Richardson Dilworth House" (2013). Theses (Historic Preservation). 213. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/213 Suggested Citation: Troppauer, Chelsea Elizabeth (2013). Go with the Faux: Re-Evaluating the Design of the Richardson Dilworth House. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/213 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Go with the Faux: Re-Evaluating the Design of the Richardson Dilworth House Abstract When elected to the office of Philadelphia's Mayor in 1956, Richardson Dilworth pledged his administration's dedication towards the physical improvement of Philadelphia. The Mayor made the revitalization of southeast quadrant of the city's core, known as Society Hill, a priority during his administration. As a symbol of his commitment, Dilworth decided to move himself and his family to the neighborhood. The Dilworths commissioned restoration architect, G. Edwin Brumbaugh. Brumbaugh designed a three and a half story, single family Colonial Revival house on the former site of two, 1840s structures. Dilworth resided in the house until his death in 1974. Discussions pertaining to the site's significance have focused narrowly on the building's associations, rather than the physical structure. -

Pennsylvania

THE Penns ylvania Magazine OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY VOLUME CXXVII Thefistorical Society of PennsylVania 1300 LOCUST STREET, PHILADELPHIA, PA 19107 2003 CONTENTS ARTICLES Page "To Stand Out in Heresy". Lucretia Mott, Liberty, and the Hysterical Woman Nancy Isenberg 7 To Render the Private Public: William Still and the Selling of The Underground Rail Road Stephen G. Hall 35 Reform in Philadelphia:JosephS. Clark, Richardson Dilworth, and the Women Who Made Reform Possible, 1947-1949 G. Terry Madonna and John Morrison McLarnon III 57 "Such a Noise in the World": Copper Mines and an American Colonial Echo to the South Sea Bubble Wayne Bodle 131 "ExtraordinaiyFreedom and greatHumility -A Reinterpretationof Deborah Franklin Jennifer Reed Fry 167 Rethinking Northern White Support for the African Colonization Movement: The Pennsylvania Colonization Society as an Agent of Emancipation Eric Burin 197 Freedom of Association in the Early Republic: The Republican Party, the Whiskey Rebellion, and the Philadelphiaand New York Cordwainers'Cases Johann N. Neem 259 "The Insanities of an Exalted Imagination'. The Troubled First Geological Survey of Pennsylvania Francis P. Boscoe 291 Civic Physiques:Public Images of Workers in Pittsburgh, 1800--1910 Edward Slavishak 309 FragmentedNationalism: Right-Wing Responses to September 11 in HistoricalContext Matthew N. Lyons 377 NOTES AND DOCUMENTS New Light on the Dark Lantern: The Initiation Rites and Ceremonies of a Know-Nothing Lodge in Shippensburg, Pennsylvania Mark Dash 89 The State of Pennsylvania:As Seen by Traugott Bromine Richard L. Bland 419 EDITORIALS Tamara Gaskell Miller 3,375 BOOK REVIEWS 101,231,339,429 INDEX Conrad Woodall 461 THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF PENNSYLVANIA OFFICERS Chair COLLIN F. -

Race, Reaction, and Reform: the Three Rs of Philadelphia School Politics, 1965-1971 Author(S): Jon S

Race, Reaction, and Reform: The Three Rs of Philadelphia School Politics, 1965-1971 Author(s): Jon S. Birger Source: The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 120, No. 3 (Jul., 1996), pp. 163-216 Published by: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20093045 . Accessed: 22/03/2011 22:11 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=hsp. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Historical Society of Pennsylvania is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. -

Notre Dame Welcomes Dr. Judith A. Dwyer As Its 4Th President Notre

Annual Report2013-14 inside VISIONSVISIONSACADEMY of NOTREAcademy DAME of de NotreNAMUR Dame de Namur FALL 2014 NotreNotre DameDame WelcomesWelcomes Dr.Dr. JudithJudith A.A. DwyerDwyer asas itsits 4th4th PresidentPresident VISIONS MAGAZINE . FALL 2014 . 1 MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT How does the Notre Dame community describe excellence? I am pleased to share this combined issue of Visions and the 2013-2014 Annual Report of Gifts with you. The magazine portion highlights the academic rigor, community engagement, and spiritual depth that continue to define our tradition of educational excellence. The report testifies to the generosity of so many members of our community, who support our mission and core values. Together, they tell the story of how the Academy honors the past, celebrates the present, and secures the future in the pioneering spirit of the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur. Judith A. Dwyer, Ph.D. How does Notre Dame describe excellence? Our students excel in academic, President artistic, and athletic achievements. Our alumnae continue to lead and achieve Eileen Wilkinson (see article on Margaret [Meg] Kane ’99, this year’s Notre Dame Award recipient, Principal on page 12). It is this legacy and dynamic learning environment that the gifts described in the Annual Report support. Jacqueline Coccia Academic Dean The “Our Time to Inspire” campaign seeks to ensure Notre Dame’s reputation Madeleine Harkins The Mansion. The Mansion continues to be a defining part of our school and our lives. as a premier Catholic academy for young women by providing an enhanced, Dean of Student Services 8 innovative, and dynamic learning environment.