Aohwmpjz2014120054q0

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View the Program Book

PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS 2021 AWARDS ACHIEVEMENT PRESERVATION e join eas us pl in at br ing le e c 1996 2021 p y r e e e a c s rs n e a rv li ati o n al 2021 PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS WEDNESDAY, JUNE 9, 2021 CONGRATULATIONS TO THE 2021 PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARD HONOREES Your knowledge, commitment, and advocacy create a better future for our city. And best wishes to the Preservation Alliance as you celebrate 25 years of invaluable service to the Greater Philadelphia region. pmcpropertygroup.com 1 PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS 2021 WELCOME TO THE 2021 PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS HONORING THE INDIVIDUALS, ORGANIZATIONS, BUSINESSES, AND PROJECTS THROUGHOUT GREATER PHILADELPHIA THAT EXEMPLIFY OUTSTANDING ACHIEVEMENT IN HISTORIC PRESERVATION TABLE OF CONTENTS Our Sponsors . 4 Executive Director’s Welcome . .. 6 Board of Directors . 8 Celebrating 25 Years: A Look Back . 9 Special Recognition Awards . 11 Advisory Committee. 11 James Biddle Award . 12 Board of Directors Award . 13 Rhoda and Permar Richards Award. 13 Economic Impact Award . 14 Preservation Education Awards . 14-15 John Andrew Gallery Community Action Awards . 15-16 Public Service Awards . 16-17 Young Friends of the Preservation Alliance Award . 17 AIA Philadelphia Henry J . Magaziner Award . .. 18 AIA Philadelphia Landmark Building Award . .. 18 Members of the Grand Jury . .. 19 Grand Jury Awards and Map . 20 In Memoriam . 46 Video by Mitlas Productions LLC | Graphic design by Peltz Creative Program editing by Fabien Communications 25TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE PRESERVATION ALLIANCE FOR GREATER PHILADELPHIA 2 3 PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS 2021 OUR SPONSORS ALABASTER PMC Property Group Brickstone IBEW Local Union 98 Post Brothers MARBLE A. -

Finding Aid for the Mellor, Meigs & Howe Collection in The

George Howe, P.S.F.S. Building, ca. 1926 THE ARCHITECTURAL ARCHIVES OF THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA MELLOR, MEIGS & HOWE COLLECTION (Collection 117) A Finding Aid for The Mellor, Meigs & Howe Collection in The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania © 2003 The Architectural Archives of the University of Pennsylvania. All rights reserved. The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania Mellor, Meigs & Howe Collection Finding Aid Archival Description Descriptive Summary Title: Mellor, Meigs & Howe Collection, 1915-1975, bulk 1915-1939. Coll. ID: 117 Origin: Mellor, Meigs & Howe, Architects, and successor, predecessor and related firms. Extent: Architectural drawings: 1004 sheets; Photographs: 83 photoprints; Boxed files: 1/2 cubic foot. Repository: The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania 102 Meyerson Hall Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-6311 (215) 898-8323 Abstract: The Mellor, Meigs & Howe Collection comprises architectural records related to the practices of Mellor, Meigs & Howe and its predecessor and successor firms. The bulk of the collection documents architectural projects of the following firms: Mellor, Meigs & Howe; Mellor & Meigs; Howe and Lescaze; and George Howe, Architect. It also contains materials related to projects of the firms William Lescaze, Architect and Louis E. McAllister, Architect. The collection also contains a small amount of personal material related to Walter Mellor and George Howe. Indexes: This collection is included in the Philadelphia Architects and Buildings Project, a searchable database of architectural research materials related to architects and architecture in Philadelphia and surrounding regions: http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org Cataloging: Collection-level records for materials in the Architectural Archives may be found in RLIN Eureka, the union catalogue of members of the Research Libraries Group. -

Penn Center Plaza Transportation Gateway Application ID 8333219 Exhibit 1: Project Description

MULTIMODAL TRANSPORTATION FUND APPLICATION Center City District: Penn Center Plaza Transportation Gateway Application ID 8333219 Exhibit 1: Project Description The Center City District (CCD), a private-sector sponsored business improvement district, authorized under the Commonwealth’s Municipality Authorities Act, seeks to improve the open area and entrances to public transit between the two original Penn Center buildings, bounded by Market Street and JFK Boulevard and 15th and 16th Streets. In 2014, the CCD completed the transformation of Dilworth Park into a first class gateway to transit and a welcoming, sustainably designed civic commons in the heart of Philadelphia. In 2018, the City of Philadelphia completed the renovations of LOVE Park, between 15th and 16th Street, JFK Boulevard and Arch Street. The adjacent Penn Center open space should be a vibrant pedestrian link between the office district and City Hall, a prominent gateway to transit and an attractive setting for businesses seeking to capitalize on direct connections to the regional rail and subway system. However, it is neither well designed nor well managed. While it is perceived and used as public space, its divided ownership between the two adjacent Penn Center buildings and SEPTA has long hampered efforts for a coordinated improvement plan. The property lines runs east/west through the middle of the plaza with Two Penn Center owning the northern half, 1515 Market owning the southern half and neither party willing to make improvements without their neighbor making similar improvements. Since it opened in the early 1960s, Penn Center plaza has never lived up to its full potential. The site was created during urban renewal with the demolition of the above ground, Broad Street Station and the elevated train tracks that ran west to 30th Street. -

TUESDAY, M Y 1, 1962 the President Met with the Following of The

TUESDAY, MAYMYI,1, 1962 9:459:45 -- 9:50 am The PrePresidentsident met with the following of the Worcester Junior Chamber of CommeCommerce,rce, MasMassachusettssachusetts in the Rose Garden: Don Cookson JJamesarne s Oulighan Larry Samberg JeffreyJeffrey Richard JohnJohn Klunk KennethKenneth ScScottott GeorgeGeorge Donatello EdwardEdward JaffeJaffe RichardRichard MulhernMulhern DanielDaniel MiduszenskiMiduszenski StazrosStazros GaniaGaniass LouiLouiss EdmondEdmond TheyThey werewere accorrpaccompaniedanied by CongresCongressmansman HaroldHarold D.D. DonohueDonohue - TUESDAY,TUESbAY J MAY 1, 1962 8:45 atn LEGISLATIVELEGI~LATIVE LEADERS BREAKFAST The{['he Vice President Speaker John W. McCormackMcCortnack Senator Mike Mansfield SenatorSenato r HubertHube rt HumphreyHUInphrey Senator George SmatherStnathers s CongressmanCongresstnan Carl Albert CongressmanCongresstnan Hale BoggBoggs s Hon. Lawrence O'Brien Hon. Kenneth O'Donnell0 'Donnell Hon. Pierre Salinger Hon. Theodore Sorensen 9:35 amatn The President arrived in the office. (See insert opposite page) 10:32 - 10:55 amatn The President mettnet with a delegation fromfrotn tktre Friends'Friends I "Witness for World Order": Henry J. Cadbury, Haverford, Pa. Founder of the AmericanAtnerican Friends Service CommitteeCOtntnittee ( David Hartsough, Glen Mills, Pennsylvania Senior at Howard University Mrs. Dorothy Hutchinson, Jenkintown, Pa. Opening speaker, the Friends WitnessWitnes~ for World Order Mr. Samuel Levering, Arararat, Virginia Chairman of the Board on Peace and.and .... Social Concerns Edward F. Snyder, College Park, Md. Executive Secretary of the Friends Committe on National Legislation George Willoughby, Blackwood Terrace, N. J. Member of the crew of the Golden Rule (ship) and the San Francisco to Moscow Peace Walk (Hon. McGeorgeMkGeorge Bundy) (General Chester V. Clifton 10:57 - 11:02 am (Congre(Congresswomansswoman Edith Green, Oregon) OFF TRECO 11:15 - 11:58 am H. -

Program Code Title Date Start Time CE Hours Description Tour Format

Tour Program Code Title Date Start Time CE Hours Description Accessibility Format ET101 Historic Boathouse Row 05/18/16 8:00 a.m. 2.00 LUs/GBCI Take an illuminating journey along Boathouse Row, a National Historic District, and tour the exteriors of 15 buildings dating from Bus and No 1861 to 1998. Get a firsthand view of a genuine labor of Preservation love. Plus, get an interior look at the University Barge Club Walking and the Undine Barge Club. Tour ET102 Good Practice: Research, Academic, and Clinical 05/18/16 9:00 a.m. 1.50 LUs/HSW/GBCI Find out how the innovative design of the 10-story Smilow Center for Translational Research drives collaboration and accelerates Bus and Yes SPaces Work Together advanced disease discoveries and treatment. Physically integrated within the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman Center for Walking Advanced Medicine and Jordan Center for Medical Education, it's built to train the next generation of Physician-scientists. Tour ET103 Longwood Gardens’ Fountain Revitalization, 05/18/16 9:00 a.m. 3.00 LUs/HSW/GBCI Take an exclusive tour of three significant historic restoration and exPansion Projects with the renowned architects and Bus and No Meadow ExPansion, and East Conservatory designers resPonsible for them. Find out how each Professional incorPorated modern systems and technologies while Walking Plaza maintaining design excellence, social integrity, sustainability, land stewardshiP and Preservation, and, of course, old-world Tour charm. Please wear closed-toe shoes and long Pants. ET104 Sustainability Initiatives and Green Building at 05/18/16 10:30 a.m. -

Historic-Register-OPA-Addresses.Pdf

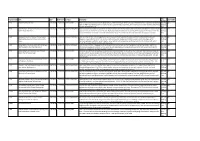

Philadelphia Historical Commission Philadelphia Register of Historic Places As of January 6, 2020 Address Desig Date 1 Desig Date 2 District District Date Historic Name Date 1 ACADEMY CIR 6/26/1956 US Naval Home 930 ADAMS AVE 8/9/2000 Greenwood Knights of Pythias Cemetery 1548 ADAMS AVE 6/14/2013 Leech House; Worrell/Winter House 1728 517 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 519 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 600-02 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 2013 601 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 603 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 604 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 605-11 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 606 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 608 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 610 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 612-14 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 613 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 615 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 616-18 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 617 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 619 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 629 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 631 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 1970 635 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 636 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 637 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 638 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 639 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 640 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 641 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 642 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 643 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 703 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 708 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 710 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 712 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 714 ADDISON ST Society Hill -

IV. Fabric Summary 282 Copyrighted Material

Eastern State Penitentiary HSR: IV. Fabric Summary 282 IV. FABRIC SUMMARY: CONSTRUCTION, ALTERATIONS, AND USES OF SPACE (for documentation, see Appendices A and B, by date, and C, by location) Jeffrey A. Cohen § A. Front Building (figs. C3.1 - C3.19) Work began in the 1823 building season, following the commencement of the perimeter walls and preceding that of the cellblocks. In August 1824 all the active stonecutters were employed cutting stones for the front building, though others were idled by a shortage of stone. Twenty-foot walls to the north were added in the 1826 season bounding the warden's yard and the keepers' yard. Construction of the center, the first three wings, the front building and the perimeter walls were largely complete when the building commissioners turned the building over to the Board of Inspectors in July 1829. The half of the building east of the gateway held the residential apartments of the warden. The west side initially had the kitchen, bakery, and other service functions in the basement, apartments for the keepers and a corner meeting room for the inspectors on the main floor, and infirmary rooms on the upper story. The latter were used at first, but in September 1831 the physician criticized their distant location and lack of effective separation, preferring that certain cells in each block be set aside for the sick. By the time Demetz and Blouet visited, about 1836, ill prisoners were separated rather than being placed in a common infirmary, and plans were afoot for a group of cells for the sick, with doors left ajar like others. -

Journal of Urban History

Journal of Urban History http://juh.sagepub.com/ ''From Protest to Politics'' : Community Control and Black Independent Politics in Philadelphia, 1965-1984 Matthew J. Countryman Journal of Urban History 2006 32: 813 DOI: 10.1177/0096144206289034 The online version of this article can be found at: http://juh.sagepub.com/content/32/6/813 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: The Urban History Association Additional services and information for Journal of Urban History can be found at: Email Alerts: http://juh.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://juh.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://juh.sagepub.com/content/32/6/813.refs.html Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at Harvard Libraries on March 22, 2011 “FROM PROTEST TO POLITICS” Community Control and Black Independent Politics in Philadelphia, 1965-1984 MATTHEW J. COUNTRYMAN University of Michigan This article traces the origins of black independent electoral activism in Philadelphia during the 1970s to the Black Power movement of the 1960s. Specifically, it argues that Black Power activists in Philadelphia turned to electoral strategies to consolidate their efforts to achieve community control over public insti- tutions in the city’s black working-class neighborhoods. Finally, the article concludes with a brief evalu- ation of the careers of African American activist state legislators David Richardson and Roxanne Jones and W. Wilson Goode, Philadelphia’s first African American mayor. Keywords: Black Power; community control; independent politics; Democratic Party The political philosophy of black nationalism means that the black man should control the politics and politicians in his own community. -

Adaptive Reuse: Recent Hotel Conversions in Downtown Philadelphia Catherine S

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 1-1-2005 Adaptive Reuse: Recent Hotel Conversions in Downtown Philadelphia Catherine S. Jefferson University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Jefferson, Catherine S., "Adaptive Reuse: Recent Hotel Conversions in Downtown Philadelphia" (2005). Theses (Historic Preservation). 30. http://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/30 Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Historic Preservation 2005. Advisor: David Hollenberg This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. http://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/30 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Adaptive Reuse: Recent Hotel Conversions in Downtown Philadelphia Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Historic Preservation 2005. Advisor: David Hollenberg This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: http://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/30 ADAPTIVE REUSE: RECENT HOTEL CONVERSIONS IN DOWNTOWN PHILADELPHIA Catherine Sarah Jefferson A THESIS in Historic Preservation Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN HISTORIC PRESERVATION 2005 _____________________________ _____________________________ Advisor Reader David Hollenberg John Milner Lecturer in Historic Preservation Adjunct Professor of Architecture _____________________________ Program Chair Frank G. Matero Associate Professor of Architecture ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the assistance and support of a number of people. -

Re-Evaluating the Design of the Richardson Dilworth House

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2013 Go with the Faux: Re-Evaluating the Design of the Richardson Dilworth House Chelsea Elizabeth Troppauer University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Troppauer, Chelsea Elizabeth, "Go with the Faux: Re-Evaluating the Design of the Richardson Dilworth House" (2013). Theses (Historic Preservation). 213. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/213 Suggested Citation: Troppauer, Chelsea Elizabeth (2013). Go with the Faux: Re-Evaluating the Design of the Richardson Dilworth House. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/213 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Go with the Faux: Re-Evaluating the Design of the Richardson Dilworth House Abstract When elected to the office of Philadelphia's Mayor in 1956, Richardson Dilworth pledged his administration's dedication towards the physical improvement of Philadelphia. The Mayor made the revitalization of southeast quadrant of the city's core, known as Society Hill, a priority during his administration. As a symbol of his commitment, Dilworth decided to move himself and his family to the neighborhood. The Dilworths commissioned restoration architect, G. Edwin Brumbaugh. Brumbaugh designed a three and a half story, single family Colonial Revival house on the former site of two, 1840s structures. Dilworth resided in the house until his death in 1974. Discussions pertaining to the site's significance have focused narrowly on the building's associations, rather than the physical structure. -

Theodore Roosevelt Middle School), in Assessor's Parcel Block No. 1061, Lot No

FILE NO. 180003 ORDINANCE NO. 37-19 1 [Planning Code - Landmark Designation - 460 Arguello Boulevard (aka Theodore Roosevelt Middle School)] 2 3 Ordinance amending the Planning Code to designate 460 Arguello Boulevard (aka 4 Theodore Roosevelt Middle School), in Assessor's Parcel Block No. 1061, Lot No. 049, 5 as a Landmark under Article 10 of the Planning Code; affirming the Planning 6 Department's determination under the California Environmental Quality Act; and 7 making public necessity, convenience, and welfare findings under Planning Code, 8 Section 302, and findings of consistency with the General Plan, and the eight priority 9 policies of Planning Code, Section 101.1. 10 NOTE: Unchanged Code text and uncodified text are in plain Ariai font. Additions to Codes are in single-underline italics Times New Roman font. 11 Deletions to Codes are in strikf!through italics Times New Roman font. Board amendment additions are in double-underlined Arial font. 12 Board amendment deletions are in strikethrough Arial font. Asterisks (* * * *) indicate the omission of unchanged Code 13 subsections or parts of tables. 14 15 Be it ordained by the People of the City and County of San Francisco: 16 Section 1. Findings. 17 (a) CEQA and Land Use Findings. 18 (1) The Planning Department has determined that the proposed Planning Code 19 amendment is subject to a Categorical Exemption from the California Environmental Quality 20 Act (California Public Resources Code section 21000 et seq., "CEQA") pursuant to Section 21 15308 of the Guidelines for implementation of the statute for actions by regulatory agencies 22 for protection of the environment (in this case, landmark designation). -

Pennsylvania

THE Penns ylvania Magazine OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY VOLUME CXXVII Thefistorical Society of PennsylVania 1300 LOCUST STREET, PHILADELPHIA, PA 19107 2003 CONTENTS ARTICLES Page "To Stand Out in Heresy". Lucretia Mott, Liberty, and the Hysterical Woman Nancy Isenberg 7 To Render the Private Public: William Still and the Selling of The Underground Rail Road Stephen G. Hall 35 Reform in Philadelphia:JosephS. Clark, Richardson Dilworth, and the Women Who Made Reform Possible, 1947-1949 G. Terry Madonna and John Morrison McLarnon III 57 "Such a Noise in the World": Copper Mines and an American Colonial Echo to the South Sea Bubble Wayne Bodle 131 "ExtraordinaiyFreedom and greatHumility -A Reinterpretationof Deborah Franklin Jennifer Reed Fry 167 Rethinking Northern White Support for the African Colonization Movement: The Pennsylvania Colonization Society as an Agent of Emancipation Eric Burin 197 Freedom of Association in the Early Republic: The Republican Party, the Whiskey Rebellion, and the Philadelphiaand New York Cordwainers'Cases Johann N. Neem 259 "The Insanities of an Exalted Imagination'. The Troubled First Geological Survey of Pennsylvania Francis P. Boscoe 291 Civic Physiques:Public Images of Workers in Pittsburgh, 1800--1910 Edward Slavishak 309 FragmentedNationalism: Right-Wing Responses to September 11 in HistoricalContext Matthew N. Lyons 377 NOTES AND DOCUMENTS New Light on the Dark Lantern: The Initiation Rites and Ceremonies of a Know-Nothing Lodge in Shippensburg, Pennsylvania Mark Dash 89 The State of Pennsylvania:As Seen by Traugott Bromine Richard L. Bland 419 EDITORIALS Tamara Gaskell Miller 3,375 BOOK REVIEWS 101,231,339,429 INDEX Conrad Woodall 461 THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF PENNSYLVANIA OFFICERS Chair COLLIN F.