Theodore Roosevelt Middle School), in Assessor's Parcel Block No. 1061, Lot No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View the Program Book

PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS 2021 AWARDS ACHIEVEMENT PRESERVATION e join eas us pl in at br ing le e c 1996 2021 p y r e e e a c s rs n e a rv li ati o n al 2021 PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS WEDNESDAY, JUNE 9, 2021 CONGRATULATIONS TO THE 2021 PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARD HONOREES Your knowledge, commitment, and advocacy create a better future for our city. And best wishes to the Preservation Alliance as you celebrate 25 years of invaluable service to the Greater Philadelphia region. pmcpropertygroup.com 1 PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS 2021 WELCOME TO THE 2021 PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS HONORING THE INDIVIDUALS, ORGANIZATIONS, BUSINESSES, AND PROJECTS THROUGHOUT GREATER PHILADELPHIA THAT EXEMPLIFY OUTSTANDING ACHIEVEMENT IN HISTORIC PRESERVATION TABLE OF CONTENTS Our Sponsors . 4 Executive Director’s Welcome . .. 6 Board of Directors . 8 Celebrating 25 Years: A Look Back . 9 Special Recognition Awards . 11 Advisory Committee. 11 James Biddle Award . 12 Board of Directors Award . 13 Rhoda and Permar Richards Award. 13 Economic Impact Award . 14 Preservation Education Awards . 14-15 John Andrew Gallery Community Action Awards . 15-16 Public Service Awards . 16-17 Young Friends of the Preservation Alliance Award . 17 AIA Philadelphia Henry J . Magaziner Award . .. 18 AIA Philadelphia Landmark Building Award . .. 18 Members of the Grand Jury . .. 19 Grand Jury Awards and Map . 20 In Memoriam . 46 Video by Mitlas Productions LLC | Graphic design by Peltz Creative Program editing by Fabien Communications 25TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE PRESERVATION ALLIANCE FOR GREATER PHILADELPHIA 2 3 PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS 2021 OUR SPONSORS ALABASTER PMC Property Group Brickstone IBEW Local Union 98 Post Brothers MARBLE A. -

Urban Change Cultural Makers and Spaces in the Ruhr Region

PART 2 URBAN CHANGE CULTURAL MAKERS AND SPACES IN THE RUHR REGION 3 | CONTENT URBAN CHANGE CULTURAL MAKERS AND SPACES IN THE RUHR REGION CONTENT 5 | PREFACE 6 | INTRODUCTION 9 | CULTURAL MAKERS IN THE RUHR REGION 38 | CREATIVE.QUARTERS Ruhr – THE PROGRAMME 39 | CULTURAL PLACEMAKING IN THE RUHR REGION 72 | IMPRINT 4 | PREFACE 5 | PREFACE PREFACE Dear Sir or Madam, Dear readers of this brochure, Individuals and institutions from Cultural and Creative Sectors are driving urban, Much has happened since the project started in 2012: The Creative.Quarters cultural and economic change – in the Ruhr region as well as in Europe. This is Ruhr are well on their way to become a strong regional cultural, urban and eco- proven not only by the investment of 6 billion Euros from the European Regional nomic brand. Additionally, the programme is gaining more and more attention on Development Fund (ERDF) that went into culture projects between 2007 and a European level. The Creative.Quarters Ruhr have become a model for a new, 2013. The Ruhr region, too, exhibits experience and visible proof of structural culturally carried and integrative urban development in Europe. In 2015, one of change brought about through culture and creativity. the projects supported by the Creative.Quarters Ruhr was even invited to make a presentation at the European Parliament in Brussels. The second volume of this brochure depicts the Creative.Quarters Ruhr as a building block within the overall strategy for cultural and economic change in the Therefore, this second volume of the brochure “Urban Change – Cultural makers Ruhr region as deployed by the european centre for creative economy (ecce). -

Excavations of Aztec Urban Houses at Yautepec, Mexico

- - EXCAVATIONSOF AZTECURBAN HOUSES AT YAUTEPEC, MEXICO Michael E. Smith, CynthiaHeath-Smith, and Lisa Montiel Our recent excavations at the site of Yautepecin the Mexican state of Morelos have uncovered a large set of residential struc- turesfrom an Aztec city. Weexcavated seven houses with associated middens, as well as several middens without architecture. In this paper, we briefly review the excavations, describe each house, and summarizethe nature of construction materials and methods employed. Wecompare the Yautepechouses with other knownAztec houses and make some preliminary inferences on the relationship between house size and wealth at the site. En nuestras excavaciones recientes en el sitio de Yautepecen el estado mexicano de Morelos, encontramosun grupo grande de casas habitacionales en una ciudad azteca. Excavamos siete casas con sus basureros,tanto como otros basurerossin arquitec- tura. En este artfeulo revisamos las excavaciones, decribimos cada casa y discutimos los patrones de materiales y me'todosde construccion. Hacemos comparaciones entre las casas de Yautepecy otras casas aztecas, y presentamosalgunas conclusiones preliminaressobre la relacion entre el tamanode las casas y la riqueza. Most Aztec urban sites today lie buried Yautepec under modern towns, and, of those that still exist as intact archaeological sites, Socialand Economic Context most have been heavily plowed, causing the Yautepecwas thecapital of a powerfulcity-state, and destruction or heavy disturbance of residential its king ruled over severalsubject city-states in the structures(Smith 1996). Intensive surface collec- YautepecRiver Valley of central Morelos (Smith tions can provide important information about 1994). This area,separated from the Valleyof Mex- social and economic patternsat these plowed sites ico to the northby theAjusco Mountains(Figure 1), (e.g., Brumfiel 1996; Charlton et al. -

Finding Aid for the Mellor, Meigs & Howe Collection in The

George Howe, P.S.F.S. Building, ca. 1926 THE ARCHITECTURAL ARCHIVES OF THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA MELLOR, MEIGS & HOWE COLLECTION (Collection 117) A Finding Aid for The Mellor, Meigs & Howe Collection in The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania © 2003 The Architectural Archives of the University of Pennsylvania. All rights reserved. The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania Mellor, Meigs & Howe Collection Finding Aid Archival Description Descriptive Summary Title: Mellor, Meigs & Howe Collection, 1915-1975, bulk 1915-1939. Coll. ID: 117 Origin: Mellor, Meigs & Howe, Architects, and successor, predecessor and related firms. Extent: Architectural drawings: 1004 sheets; Photographs: 83 photoprints; Boxed files: 1/2 cubic foot. Repository: The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania 102 Meyerson Hall Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-6311 (215) 898-8323 Abstract: The Mellor, Meigs & Howe Collection comprises architectural records related to the practices of Mellor, Meigs & Howe and its predecessor and successor firms. The bulk of the collection documents architectural projects of the following firms: Mellor, Meigs & Howe; Mellor & Meigs; Howe and Lescaze; and George Howe, Architect. It also contains materials related to projects of the firms William Lescaze, Architect and Louis E. McAllister, Architect. The collection also contains a small amount of personal material related to Walter Mellor and George Howe. Indexes: This collection is included in the Philadelphia Architects and Buildings Project, a searchable database of architectural research materials related to architects and architecture in Philadelphia and surrounding regions: http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org Cataloging: Collection-level records for materials in the Architectural Archives may be found in RLIN Eureka, the union catalogue of members of the Research Libraries Group. -

Penn Center Plaza Transportation Gateway Application ID 8333219 Exhibit 1: Project Description

MULTIMODAL TRANSPORTATION FUND APPLICATION Center City District: Penn Center Plaza Transportation Gateway Application ID 8333219 Exhibit 1: Project Description The Center City District (CCD), a private-sector sponsored business improvement district, authorized under the Commonwealth’s Municipality Authorities Act, seeks to improve the open area and entrances to public transit between the two original Penn Center buildings, bounded by Market Street and JFK Boulevard and 15th and 16th Streets. In 2014, the CCD completed the transformation of Dilworth Park into a first class gateway to transit and a welcoming, sustainably designed civic commons in the heart of Philadelphia. In 2018, the City of Philadelphia completed the renovations of LOVE Park, between 15th and 16th Street, JFK Boulevard and Arch Street. The adjacent Penn Center open space should be a vibrant pedestrian link between the office district and City Hall, a prominent gateway to transit and an attractive setting for businesses seeking to capitalize on direct connections to the regional rail and subway system. However, it is neither well designed nor well managed. While it is perceived and used as public space, its divided ownership between the two adjacent Penn Center buildings and SEPTA has long hampered efforts for a coordinated improvement plan. The property lines runs east/west through the middle of the plaza with Two Penn Center owning the northern half, 1515 Market owning the southern half and neither party willing to make improvements without their neighbor making similar improvements. Since it opened in the early 1960s, Penn Center plaza has never lived up to its full potential. The site was created during urban renewal with the demolition of the above ground, Broad Street Station and the elevated train tracks that ran west to 30th Street. -

Program Code Title Date Start Time CE Hours Description Tour Format

Tour Program Code Title Date Start Time CE Hours Description Accessibility Format ET101 Historic Boathouse Row 05/18/16 8:00 a.m. 2.00 LUs/GBCI Take an illuminating journey along Boathouse Row, a National Historic District, and tour the exteriors of 15 buildings dating from Bus and No 1861 to 1998. Get a firsthand view of a genuine labor of Preservation love. Plus, get an interior look at the University Barge Club Walking and the Undine Barge Club. Tour ET102 Good Practice: Research, Academic, and Clinical 05/18/16 9:00 a.m. 1.50 LUs/HSW/GBCI Find out how the innovative design of the 10-story Smilow Center for Translational Research drives collaboration and accelerates Bus and Yes SPaces Work Together advanced disease discoveries and treatment. Physically integrated within the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman Center for Walking Advanced Medicine and Jordan Center for Medical Education, it's built to train the next generation of Physician-scientists. Tour ET103 Longwood Gardens’ Fountain Revitalization, 05/18/16 9:00 a.m. 3.00 LUs/HSW/GBCI Take an exclusive tour of three significant historic restoration and exPansion Projects with the renowned architects and Bus and No Meadow ExPansion, and East Conservatory designers resPonsible for them. Find out how each Professional incorPorated modern systems and technologies while Walking Plaza maintaining design excellence, social integrity, sustainability, land stewardshiP and Preservation, and, of course, old-world Tour charm. Please wear closed-toe shoes and long Pants. ET104 Sustainability Initiatives and Green Building at 05/18/16 10:30 a.m. -

View Full Itinerary (Pdf)

HOST Hamburg Marketing www.marketing.hamburg.de FAM Trip Hamburg Jessica Schmidt 2018 Project Manager Media Relations Phone: +49 (0) 40 300 51-581 Mobile: +49 (0) 174 91 77 17 9 [email protected] WELCOME TO HAMBURG Hamburg – Beautiful period apartments or ultra-modern new buildings, the It is the world’s largest coherent tranquility of parks and waterways or warehouse complex and includes a the hustle and bustle of the city centre: number of interesting museums and shaped by contrast, the Hanseatic City exciting exhibitions. of Hamburg demonstrates that nature and urban life make a perfect match. The Elbphilharmonie Hamburg Hamburg’s iconic concert venue and new Speicherstadt and HafenCity: tradition landmark, the Elbphilharmonie Hamburg, and modernity is located at the western tip of the HafenCity district. Ever since its official With the HafenCity Hamburg, an entirely opening on 11 and 12 January 2017, the new urban quarter of town is currently Elbphilharmonie has become a true taking shape on more than 150 hectares magnet for Hamburg’s locals and guests of former port land. Located in the very from around the globe. Situated directly on heart of the city, the innovative the River Elbe and surrounded by water architectural design of the HafenCity’s on three sides, the spectacular building office and residential buildings and the includes three concert halls, a large music spacious Magellan Terrassen and Marco education area, a restaurant, a hotel, and Polo Terrassen directly on the waterfront the Plaza – a public viewing platform that make the HafenCity well worth exploring. offers a unique panoramic view of the city. -

Welcome to Gelsenkirchen

Welcome to Gelsenkirchen Publisher: City of Gelsenkirchen The Mayor Public Relations Unit in collaboration with Stadtmarketing Gesellschaft Gelsenkirchen mbH Photographs: Gerd Kaemper, Pedro Malinowski, Thomas Robbin, Martin Schmüderich, Caroline Seidel, Franz Weiß, City of Gelsenkirchen Simply select Free WiFi Gelsen- kirchen WLAN and surf away for free at ultra-high speed on the Ruhrgebiet‘s largest hotspot network. freewifi.gelsenkirchen.de Münster/Osnabrück Interesting facts about Gelsenkirchen Gelsenkirchen is situated in the middle of the Ruhr metropolitan region, after Paris and London the third-largest conurbation in Europe. RUHRGEBIET Over five million people live here. For around 30 million people Gelsenkirchen can be reached inside two hours. Around 40 percent of the population of the European Union live within a 500-kilometre radius of the city. Gelsenkirchen has around 265,000 residents. Gelsenkirchen is easy to get to: both by car, via the A2, A42, A52, A31, A40 and A43 motorways, and by local public transport or mainline train. Within a radius of just 100 kilometres there are four airports. In Gelsenkirchen and its immediate vicinity you will findthree golf clubs, including two 18- hole courses. One of Germany‘s biggest solar power residential estates, comprising 422 flats, is located in Gelsenkirchen. There are also other solar power estates within the city and directly adjacent to the VELTINS-Arena 'auf Schalke' the eye is caught by an enormous solar sail. 2 3 ULTRAMARIN Gelsenkirchen and the colour blue belong together. Yes. But it is not the royal blue of FC Schalke 04, as many football fans would like to think. -

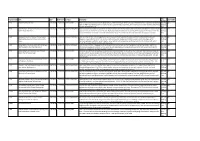

Historic-Register-OPA-Addresses.Pdf

Philadelphia Historical Commission Philadelphia Register of Historic Places As of January 6, 2020 Address Desig Date 1 Desig Date 2 District District Date Historic Name Date 1 ACADEMY CIR 6/26/1956 US Naval Home 930 ADAMS AVE 8/9/2000 Greenwood Knights of Pythias Cemetery 1548 ADAMS AVE 6/14/2013 Leech House; Worrell/Winter House 1728 517 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 519 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 600-02 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 2013 601 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 603 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 604 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 605-11 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 606 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 608 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 610 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 612-14 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 613 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 615 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 616-18 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 617 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 619 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 629 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 631 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 1970 635 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 636 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 637 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 638 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 639 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 640 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 641 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 642 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 643 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 703 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 708 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 710 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 712 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 714 ADDISON ST Society Hill -

NPS Form 10 900 OMB No. 1024 0018

NPS Form 10-900 (Rev. 8/2002) OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 1-31- 2009) United States Department of the Interior Draft National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property Historic name Four Fifty Sutter Building Other names/site number 450 Sutter Building; Medical-Dental Building; Four Fifty Building 2. Location street & number 450 Sutter Street N/A not for publication city of town San Francisco N/A vicinity State California code CA county San Francisco code 075 zip code 94108 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this _ nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Agenda and Summary of Outcomes

ICCT Technical Workshop on Zero Emission Vessel Technology San Francisco, 2019 InterContinental Mark Hopkins Hotel San Francisco, California, USA 9-10 July 2019 Goal and Agenda Dan Rutherford, PhD Director, ICCT Marine & Aviation Programs ICCT Technical Workshop on Zero Emission Vessel Technology InterContinental Mark Hopkins Hotel San Francisco, California, USA 9-10 July 2019 Welcome to San Francisco, California! https://traveldigg.com/golden-gate-bridge-san-francisco-the-most-popular-tourist-attractions-in-america/ 3 IMO’s Initial GHG Strategy 4 Workshop Goal Goal: Discuss technology pathways and barriers to zero-emission international shipping to help identify related research, development, and demonstration needs. 5 Workshop Output Output: A workshop summary document that can inform ongoing discussions at the International Maritime Organization on funding for zero- and low- carbon technologies for international shipping. 6 Day 1 Agenda (1/2) Time Activity 9:00-9:30 Registration, coffee/tea and a light breakfast 9:30-9:45 Review of agenda and workshop goals (Dan Rutherford, ICCT) Setting the stage: A proposal to establish a Board to accelerate RDD&D of ZEVs for 9:45-10:00 international shipping (Bryan Wood-Thomas, WSC) Hydrogen, fuel cells, and batteries 10:00-11:00 • Hydrogen co-combustion in ICE (Roy Campe, CMB) • Electric and H2 fuel cell ships in China (Guiyang Ling, Commission Office of Shanghai Port) 11:00-11:15 Coffee/Tea Break Wind-assist: opportunities for existing and new ships 11:15-11:45 • Wind-assist technologies (Jay -

Your Guide to Hamburg

Hamburg in collaboration with Hamburg Tourismus GmbH Photo: CooperCopter GmbH Elbe and Alster Lake, the historic Town Hall, the UNESCO World Heritage Site Speicherstadt and Kontorhaus District with Chilehaus, the nightlife on the famous Reeperbahn and the traditional Hamburg fish market shape the image of Hamburg, Germany’s green city on the waterfront. The HafenCity offers modern architecture and the new landmark, the concert hall Elphilharmonie Hamburg. In Hamburg prestige, elegance and modernity are combined to a globally unique atmosphere. ©Jörg Modrow_www.mediaserver.hamburg.de Top 5 Elbphilharmonie Plaza - Ex... The Plaza is the central meeting place in the Elbphilharmonie and forms the ... Panoramic views from “Michel” Hamburg has many large churches - but only one "Michel": On its platform 132... Paddling on the Alster lake Hamburg Tourismus GmbH The 160-hectare lake in the heart of the city is a true paradise for sailors... Blankenese – “the Pearl of... The former fishing and pilot village to the west of Hamburg is located right... Follow the steps of the Be... The Beatles laid the foundation stone of their career in the early 1960s in ... Hamburg Tourismus GmbH Updated 12 November 2019 Destination: Hamburg Publishing date: 2019-11-12 THE CITY HAMBURG CARD Hamburg Tourismus GmbH Hamburg Tourismus GmbH A distinct maritime character and international Perfect for your city tour! outlook make the Hanseatic city of Hamburg one Discover more – pay less: of Europe's nest destinations. Urban sparkle and natural beauty are the hallmarks of Unlimited travel by bus, train and harbour ferry Hamburg, which boasts a wide range of hotels, (HVV - Hamburg Transport Association) and restaurants, theatres and shops, chic beaches discounts at more than 150 tourist attractions! along the Elbe river, the verdant banks of the With the discovery ticket, you can explore Alster, a buzzing port district and landmarks Hamburg conveniently, exibly and aordably at reecting more than 1,200 years of history.