Vietnamese Esoterica and the Chinese Mystical Model

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Integrating Việt Nam Into World History Surveys

Southeast Asia in the Humanities and Social Science Curricula Integrating Việt Nam into World History Surveys By Mauricio Borrero and Tuan A. To t is not an exaggeration to say that the Việt Nam War of the 1960–70s emphasize to help students navigate the long span of world history surveys. remains the major, and sometimes only, point of entry of Việt Nam Another reason why world history teachers are often inclined to teach into the American imagination. Tis is true for popular culture in Việt Nam solely in the context of war is the abundance of teaching aids general and the classroom in particular. Although the Việt Nam War centered on the Việt Nam War. There is a large body of films and docu- ended almost forty years ago, American high school and college stu- mentaries about the war. Many of these films feature popular American dents continue to learn about Việt Nam mostly as a war and not as a coun- actors such as Sylvester Stallone, Tom Berenger, and Tom Cruise. There Itry. Whatever coverage of Việt Nam found in history textbooks is primar- are also a large number of games and songs about the war, as well as sub- ily devoted to the war. Beyond the classroom, most materials about Việt stantial news coverage of veterans and the Việt Nam War whenever the Nam available to students and the general public, such as news, literature, United States engages militarily in any part of the world. American lit- games, and movies, are also related to the war. Learning about Việt Nam as erature, too, has a large selection of memoirs, diaries, history books, and a war keeps students from a holistic understanding of a thriving country of novels about the war. -

Narratives of Identity and Adaptation from Persian Baha'i Refugees in Australia

Ahliat va Masir (Roots and Routes) Narratives of identity and adaptation from Persian Baha'i refugees in Australia. Ruth Williams Bachelor of Arts (Monash University) Bachelor of Teaching (Hons) (University of Melbourne) This thesis is submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Behavioural and Social Sciences and Humanities University of Ballarat, PO Box 663, University Drive, Mount Helen, Ballarat, Victoria, 3353, Australia Submitted for examination in December 2008. 1 Abstract This study aims to discover what oral history narratives reveal about the post- migration renegotiation of identity for seven Persian Baha'i refugees and to assess the ensuing impact on their adaptation to Australia. Oral history interviewing was used as the methodology in this research and a four-part model of narrative classification was employed to analyse the oral history interviews. This small-scale, case study research offers in-depth insights into the process of cross- cultural renegotiation of identities and of adaptation to new situations of a group who do not reflect the generally negative outcomes of refugees. Such a method fosters greater understanding and sensitivity than may be possible in broad, quantitative studies. This research reveals the centrality of religion to the participants' cosmopolitan and hybrid identities. The Baha'i belief system facilitates the reidentification and adaptation processes through advocating such aspects as intermarriage and dispersal amongst the population. The dual themes of separateness and belonging; continuity and change; and communion and agency also have considerable heuristic value in understanding the renegotiation of identity and adaptation. Participants demonstrate qualities of agency by becoming empowered, self-made individuals, who are represented in well-paid occupations with high status qualifications. -

Dr. Roy Murphy

US THE WHO, WHAT & WHY OF MANKIND Dr. Roy Murphy Visit us online at arbium.com An Arbium Publishing Production Copyright © Dr. Roy Murphy 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the copyright owner. Nor can it be circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without similar condition including this condition being imposed on a subsequent purchaser. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Cover design created by Mike Peers Visit online at www.mikepeers.com First Edition – 2013 ISBN 978-0-9576845-0-8 eBook-Kindle ISBN 978-0-9576845-1-5 eBook-PDF Arbium Publishing The Coach House 7, The Manor Moreton Pinkney Northamptonshire NN11 3SJ United Kingdom Printed in the United Kingdom Vi Veri Veniversum Vivus Vici 863233150197864103023970580457627352658564321742494688920065350330360792390 084562153948658394270318956511426943949625100165706930700026073039838763165 193428338475410825583245389904994680203886845971940464531120110441936803512 987300644220801089521452145214347132059788963572089764615613235162105152978 885954490531552216832233086386968913700056669227507586411556656820982860701 449731015636154727292658469929507863512149404380292309794896331535736318924 980645663415740757239409987619164078746336039968042012469535859306751299283 295593697506027137110435364870426383781188694654021774469052574773074190283 -

New Religions in Global Perspective

New Religions in Global Perspective New Religions in Global Perspective is a fresh in-depth account of new religious movements, and of new forms of spirituality from a global vantage point. Ranging from North America and Europe to Japan, Latin America, South Asia, Africa and the Caribbean, this book provides students with a complete introduction to NRMs such as Falun Gong, Aum Shinrikyo, the Brahma Kumaris movement, the Ikhwan or Muslim Brotherhood, Sufism, the Engaged Buddhist and Neo-Hindu movements, Messianic Judaism, and African diaspora movements including Rastafarianism. Peter Clarke explores the innovative character of new religious movements, charting their cultural significance and global impact, and how various religious traditions are shaping, rather than displacing, each other’s understanding of notions such as transcendence and faith, good and evil, of the meaning, purpose and function of religion, and of religious belonging. In addition to exploring the responses of governments, churches, the media and general public to new religious movements, Clarke examines the reactions to older, increasingly influential religions, such as Buddhism and Islam, in new geographical and cultural contexts. Taking into account the degree of continuity between old and new religions, each chapter contains not only an account of the rise of the NRMs and new forms of spirituality in a particular region, but also an overview of change in the regions’ mainstream religions. Peter Clarke is Professor Emeritus of the History and Sociology of Religion at King’s College, University of London, and a professorial member of the Faculty of Theology, University of Oxford. Among his publications are (with Peter Byrne) Religion Defined and Explained (1993) and Japanese New Religions: In Global Perspective (ed.) (2000). -

Cultural Additivity: Behavioural Insights from the Interaction of Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism in Folktales

ARTICLE DOI: 10.1057/s41599-018-0189-2 OPEN Cultural additivity: behavioural insights from the interaction of Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism in folktales Quan-Hoang Vuong 1, Quang-Khiem Bui2, Viet-Phuong La3, Thu-Trang Vuong4, Viet-Ha T. Nguyen1, Manh-Toan Ho1, Hong-Kong T. Nguyen 3 & Manh-Tung Ho 1,5,6 1234567890():,; ABSTRACT Computational folkloristics, which is rooted in the movement to make folklore studies more scientific, has transformed the way researchers in humanities detect patterns of cultural transmission in large folklore collections. This interdisciplinary study contributes to the literature through its application of Bayesian statistics in analyzing Vietnamese folklore. By breaking down 307 stories in popular Vietnamese folktales and major story collections and categorizing their core messages under the values or anti-values of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism, the study shows how the Bayesian method helps discover an underlying behavioural phenomenon called “cultural additivity.” The term, which is inspired by the principle of additivity in probability, adds to the voluminous works on syncretism, creolization and hybridity in its technical dimension. Here, to evaluate how the values and norms of the aforementioned three religions (“tam giáo” 三教) co-exist, interact, and influ- ence Vietnamese society, the study proposes three models of additivity for religious faiths: (a) no additivity, (b) simple additivity, and (c) complex additivity. The empirical results confirm the existence of “cultural additivity” : not only is there an isolation of Buddhism in the folktales, there is also a higher possibility of interaction or addition of Confucian and Taoist values even when these two religions hold different value systems (β{VT.VC} = 0.86). -

9789004226487.Pdf

Handbook of New Religions and Cultural Production Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion Series Editors Carole M. Cusack, University of Sydney James R. Lewis, University of Tromsø Editorial Board Olav Hammer, University of Southern Denmark Charlotte Hardman, University of Durham Titus Hjelm, University College London Adam Possamai, University of Western Sydney Inken Prohl, University of Heidelberg VOLUME 4 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.nl/bhcr Handbook of New Religions and Cultural Production Edited by Carole M. Cusack and Alex Norman LEIDEN • BOSTON 2012 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Handbook of new religions and cultural production / edited by Carole M. Cusack and Alex Norman. p. cm. — (Brill handbooks on contemporary religion, ISSN 1874–6691 ; v. 4) Includes index. ISBN 978-90-04-22187-1 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Religion and culture. I. Cusack, Carole M., 1962– II. Norman, Alex. BL65.C8H365 2012 200.9’04—dc23 2011052361 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.nl/brill-typeface. ISSN 1874-6691 ISBN 978 90 04 22187 1 (hardback) ISBN 978 90 04 22648 7 (e-book) Copyright 2012 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers and Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. -

A Study on Religion

A Study on Religion Religious studies is the academic field of multi-disciplinary, secular study of religious beliefs, behaviors, and institutions. It describes, compares, interprets, and explains religion, emphasizing systematic, historically based, and cross-cultural perspectives. While theology attempts to understand the nature of transcendent or supernatural forces (such as deities), religious studies tries to study religious behavior and belief from outside any particular religious viewpoint. Religious studies draws upon multiple disciplines and their methodologies including anthropology, sociology, psychology, philosophy, and history of religion. Religious studies originated in the nineteenth century, when scholarly and historical analysis of the Bible had flourished, and Hindu and Buddhist texts were first being translated into European languages. Early influential scholars included Friedrich Max Müller, in England, and Cornelius P. Tiele, in the Netherlands. Today religious studies is practiced by scholars worldwide. In its early years, it was known as Comparative Religion or the Science of Religion and, in the USA, there are those who today also know the field as the History of religion (associated with methodological traditions traced to the University of Chicago in general, and in particular Mircea Eliade, from the late 1950s through to the late 1980s). The field is known as Religionswissenschaft in Germany and Sciences de la religion in the French-speaking world. The term "religion" originated from the Latin noun "religio", that was nominalized from one of three verbs: "relegere" (to turn to constantly/observe conscientiously); "religare" (to bind oneself [back]); and "reeligare" (to choose again).[1] Because of these three different meanings, an etymological analysis alone does not resolve the ambiguity of defining religion, since each verb points to a different understanding of what religion is.[2] During the Medieval Period, the term "religious" was used as a noun to describe someone who had joined a monastic order (a "religious"). -

Hoskins, Janet

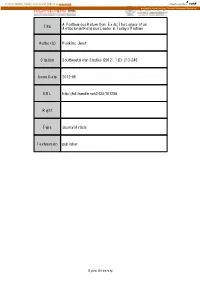

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository A Posthumous Return from Exile: The Legacy of an Title Anticolonial Religious Leader in Today's Vietnam Author(s) Hoskins, Janet Citation Southeast Asian Studies (2012), 1(2): 213-246 Issue Date 2012-08 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/167298 Right Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University A Posthumous Return from Exile: The Legacy of an Anticolonial Religious Leader in Today’s Vietnam Janet Hoskins* The 2006 return of the body Phạm Công Tắc, one of the founding spirit mediums of Caodaism and its most famous 20th century leader, re-awakened controversies about his life and legacy among Caodaists both in Vietnam and in the diaspora. This paper argues that his most important contribution lay in formulating a utopian project to support the struggle for independence by providing a religiously based repertoire of concepts to imagine national autonomy, and a separate apparatus of power to achieve it. Rather than stressing Tắc’s political actions, which have been well documented in earlier studies (Blagov 2001; Bernard Fall 1955; Werner 1976), I focus instead on a reading of his sermons, his séance transcripts and commentaries, histories published both in Vietnam and in the diaspora, and conversations with Caodaists in several countries when the appropriateness of returning his body was being debated. Keywords: Vietnamese religion, anti-colonial struggle, diaspora, postcolonial theory On November 1, 2006, excited crowds in Tây Ninh gathered in front of the huge central gate to their sacred city, which had not been opened for half a century. -

What Are Vietnam's Indigenous Religions?

No.64 Autumn 2011 What Are Vietnam’s Indigenous Religions? Janet Hoskins ........................................................................................ 3 Does Popular Culture Matter to the Southeast Asian Region? Possible Implications and Methodological Challenges Nissim Otmazgin ................................................................................... 7 Seeing Genocide and Reconciliation in Cambodia through a Village Kobayashi Satoru ................................................................................. 11 Exploring Urban Transformation of Hanoi in the French Colonial Period: An Area Informatics Approach Shibayama Mamoru ............................................................................. 13 !"#$%&'()$*+,+-#(.$'/$0'1,234$5#]#7,+'(.$'($8+932(,$:'3;#3 Spaces and Expressions of Community and Agency Aya Fabros ............................................................................................ 16 <(='(#.+2($>#12?#$8+932(,$:'3;#3.$2(=$,"#+3$&2332,+@#. Jafar Suryomenggolo ............................................................................ 20 The “Baybayin Stones” of Ticao, Masbate (Philippines) Ramon Guillermo ................................................................................. 22 *2.+('.$+($A'3=#3$!'B(.$+($,"#$8#;'(9$CDEF5#9+'( Thanyathip Sripana ..............................................................................25 G,"$0H','$I(+@#3.+,H$C'D,"#2.,$J.+2($>'3D1$2(= KU Japanese Alumni Association Mario Lopez ......................................................................................... -

CONCLUSION the Development of Caodai Sectarianism Has Aided And

CONCLUSION The development of Caodai sectarianism has aided and hindered the religion. Whether or not one accepts the claim of some Caodaists that schism and division in Caodaism were inevitable because of the fore ordination of the Creator is not of great import. The real issue involves the results of sectarianism on the religion. Caodaism seems to have been helped by the formation of new sects committed to fresh interpretations inasmuch as such schism forced the creation of other new sects and organizations. These, in turn, led to expanded proselytism, and the result has been that in the process many new converts were gained. Caodaism has moved in the past two or three decades to become a major religious and social force in Vietnam. Further, the constant need to redefine goals and purposes has effected a self-conscious identity, so that Caodai followers have managed to protect themselves and their recently recognized religion from poten tially devastating assaults by the colonial and communist forces. More over, the appearance of new Caodai sects and organizations has cer tainly aided in the development within of the philosophical base of the religion; books and pamphlets have been written, and conferences have been held in which alternatives to interested Vietnamese who were not attracted to the authoritarianism of Tay Ninh were articulated. No longer is authoritarian Tay Ninh the only option available to persons both already within Caodaism or to those yet to be converted; there is also the attraction of the more balanced perspective of the Danang sect, or the self-cultivation emphasis of the Chieu Minh Tam Thanh move ment. -

Can a Hierarchical Religion Survive Without Its Center? Caodaism, Colonialism, and Exile

Chapter 4 Can a Hierarchical Religion Survive without Its Center? Caodaism, Colonialism, and Exile Janet Hoskins he new religion of Caodaism has been described both as a form of T“Vietnamese traditionalism” (Blagov 2001) and “hybrid modernity” (Thompson 1937). It has been seen both as conservative and outrageous, nostalgic and futuristic. This paper explores that meddling of different oppositions in a religion which Clifford Geertz has called “un syncrétism à l’outrance”—an excessive, even transgressive blending of piety and blas- phemy, respectful obeisance and rebellious expressionism, the old and the new. These apparently contradictory descriptions of Caodaism revolve around its relation to hierarchy, and in particular the ways in which its new teachings have played havoc with the hierarchy of the races in co- lonial Indochina, the hierarchy of the sexes in East Asian traditions, and the hierarchy of religion and politics in French Indochina, the Republic of South Vietnam, and the postwar Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Since the fall of Saigon in 1975, the exodus of several million Vietnamese has brought Caodaism to the United States, Canada, Australia, and Europe, with the largest congregations in California. Separated from religious cen- ters in Vietnam, which were largely closed down for about twenty years, overseas Caodaists have had to consider how to revise the hierarchies of their faith in a new land, and whether to focus on diasporic virtual com- munities or evangelizing a global faith of unity. The new forms of hierarchy which emerged in French Indochina in the 1920s were born in the context of anticolonial, nationalist resistance, which created an alliance between former mandarins trying to restore Vietnam’s cultural heritage and young civil servants interested in poetic experimentation, spiritism, and social revolution. -

Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University Book Reviews 135

http://englishkyoto-seas.org/ <Book Review> Dat Manh Nguyen Janet Alison Hoskins. The Divine Eye and the Diaspora: Vietnamese Syncretism Becomes Transpacific Caodaism. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2015. Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 7, No. 1, April 2018, pp. 135-138. How to Cite: Nguyen, Dat Manh. Review of The Divine Eye and the Diaspora: Vietnamese Syncretism Becomes Transpacific Caodaism by Janet Alison Hoskins. Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 7, No. 1, April 2018, pp. 135-138. Link to this book review: https://englishkyoto-seas.org/2018/04/vol-7-no-1-book-reviews-dat-manh-nguyen/ View the table of contents for this issue: https://englishkyoto-seas.org/2018/04/vol-7-no-1-of-southeast-asian-studies/ Subscriptions: http://englishkyoto-seas.org/mailing-list/ For permissions, please send an e-mail to: [email protected] Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University Book Reviews 135 The Divine Eye and the Diaspora: Vietnamese Syncretism Becomes Transpacific Caodaism JANET ALISON HOSKINS Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2015. Founded in 1926 in colonial Cochinchina, Caodaism remains one of the least understood Vietnam- ese religious traditions. Although the Great Temple of Caodaism in Tây Ninh attracts thousands of visitors each year, most people stop at an impressionistic understanding of the tradition, marvel- ing at the colorful architecture, the eclectic veneration of Eastern and Western religious figures, and elaborate ceremonies. However, carved into this spectacle is a story of religious imagination and political schisms, of struggles against colonization, of desires for national sovereignty and reconciliation, and of the establishment of a global Vietnamese community in the diaspora.