Cultural Additivity: Behavioural Insights from the Interaction of Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism in Folktales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Living of Religious and Belief in Vietnamese History Pjaee, 18(7) (2021)

THE LIVING OF RELIGIOUS AND BELIEF IN VIETNAMESE HISTORY PJAEE, 18(7) (2021) THE LIVING OF RELIGIOUS AND BELIEF IN VIETNAMESE HISTORY Trinh Thi Thanh University of Transport and Communications, No.3 CauGiay Street, Lang Thuong Ward, Dong Da District, Hanoi, Vietnam. Trinh Thi Thanh , The Living Of Religious And Belief In Vietnamese History , Palarch’s Journal Of Archaeology Of Egypt/Egyptology 18(7). ISSN 1567-214x. Keywords: The living of religious and belief,feudal dynasties, history, Vietnamese. ABSTRACT: Vietnam is a country with many religions and beliefs. Vietnamese people have a long tradition of living and religious activities. The ethnic groups in the Vietnamese ethnic community have their own beliefs associated with their economic and spiritual life. Currently, Vietnam has about 95% of the population having beliefs and religions but their beliefs are not deep, one believes in many different types of beliefs or follows both religion and beliefs. In Vietnam, there are about 45,000 establishments with about 15,000 people specializing in religious activities, and there are nearly 8,000 festivals. Historically and in the present, all religions in Vietnam have the direction and motto of the practice of sticking with the nation, actively participating in patriotic emulation campaigns and movements on the scale, along with the government solving people's difficulties, and oriented development of religious resources have brought into play well, serving the cause of national construction. This research focuses on analyzing religious belief activities in history (from the Ly Dynasty to Tay Son Dynasty), from there giving comments and assessment of the position and son of religions in the process development of the nation. -

Integrating Việt Nam Into World History Surveys

Southeast Asia in the Humanities and Social Science Curricula Integrating Việt Nam into World History Surveys By Mauricio Borrero and Tuan A. To t is not an exaggeration to say that the Việt Nam War of the 1960–70s emphasize to help students navigate the long span of world history surveys. remains the major, and sometimes only, point of entry of Việt Nam Another reason why world history teachers are often inclined to teach into the American imagination. Tis is true for popular culture in Việt Nam solely in the context of war is the abundance of teaching aids general and the classroom in particular. Although the Việt Nam War centered on the Việt Nam War. There is a large body of films and docu- ended almost forty years ago, American high school and college stu- mentaries about the war. Many of these films feature popular American dents continue to learn about Việt Nam mostly as a war and not as a coun- actors such as Sylvester Stallone, Tom Berenger, and Tom Cruise. There Itry. Whatever coverage of Việt Nam found in history textbooks is primar- are also a large number of games and songs about the war, as well as sub- ily devoted to the war. Beyond the classroom, most materials about Việt stantial news coverage of veterans and the Việt Nam War whenever the Nam available to students and the general public, such as news, literature, United States engages militarily in any part of the world. American lit- games, and movies, are also related to the war. Learning about Việt Nam as erature, too, has a large selection of memoirs, diaries, history books, and a war keeps students from a holistic understanding of a thriving country of novels about the war. -

Narratives of Identity and Adaptation from Persian Baha'i Refugees in Australia

Ahliat va Masir (Roots and Routes) Narratives of identity and adaptation from Persian Baha'i refugees in Australia. Ruth Williams Bachelor of Arts (Monash University) Bachelor of Teaching (Hons) (University of Melbourne) This thesis is submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Behavioural and Social Sciences and Humanities University of Ballarat, PO Box 663, University Drive, Mount Helen, Ballarat, Victoria, 3353, Australia Submitted for examination in December 2008. 1 Abstract This study aims to discover what oral history narratives reveal about the post- migration renegotiation of identity for seven Persian Baha'i refugees and to assess the ensuing impact on their adaptation to Australia. Oral history interviewing was used as the methodology in this research and a four-part model of narrative classification was employed to analyse the oral history interviews. This small-scale, case study research offers in-depth insights into the process of cross- cultural renegotiation of identities and of adaptation to new situations of a group who do not reflect the generally negative outcomes of refugees. Such a method fosters greater understanding and sensitivity than may be possible in broad, quantitative studies. This research reveals the centrality of religion to the participants' cosmopolitan and hybrid identities. The Baha'i belief system facilitates the reidentification and adaptation processes through advocating such aspects as intermarriage and dispersal amongst the population. The dual themes of separateness and belonging; continuity and change; and communion and agency also have considerable heuristic value in understanding the renegotiation of identity and adaptation. Participants demonstrate qualities of agency by becoming empowered, self-made individuals, who are represented in well-paid occupations with high status qualifications. -

Dr. Roy Murphy

US THE WHO, WHAT & WHY OF MANKIND Dr. Roy Murphy Visit us online at arbium.com An Arbium Publishing Production Copyright © Dr. Roy Murphy 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the copyright owner. Nor can it be circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without similar condition including this condition being imposed on a subsequent purchaser. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Cover design created by Mike Peers Visit online at www.mikepeers.com First Edition – 2013 ISBN 978-0-9576845-0-8 eBook-Kindle ISBN 978-0-9576845-1-5 eBook-PDF Arbium Publishing The Coach House 7, The Manor Moreton Pinkney Northamptonshire NN11 3SJ United Kingdom Printed in the United Kingdom Vi Veri Veniversum Vivus Vici 863233150197864103023970580457627352658564321742494688920065350330360792390 084562153948658394270318956511426943949625100165706930700026073039838763165 193428338475410825583245389904994680203886845971940464531120110441936803512 987300644220801089521452145214347132059788963572089764615613235162105152978 885954490531552216832233086386968913700056669227507586411556656820982860701 449731015636154727292658469929507863512149404380292309794896331535736318924 980645663415740757239409987619164078746336039968042012469535859306751299283 295593697506027137110435364870426383781188694654021774469052574773074190283 -

Freedom of Belief and Religion in Vietnam: Activities of Beliefs, Religious and Policies Pjaee, 18(4) (2021)

FREEDOM OF BELIEF AND RELIGION IN VIETNAM: ACTIVITIES OF BELIEFS, RELIGIOUS AND POLICIES PJAEE, 18(4) (2021) FREEDOM OF BELIEF AND RELIGION IN VIETNAM: ACTIVITIES OF BELIEFS, RELIGIOUS AND POLICIES Huynh Thi Gam Academy of Politics Region II, Ho Chi Minh National Academy of Politics, No. 99 Man Thien Street, HiepPhu Ward, District 9, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Huynh Thi Gam , Freedom Of Belief And Religion In Vietnam: Activities Of Beliefs, Religious And Policies , Palarch’s Journal Of Archaeology Of Egypt/Egyptology 18(4). ISSN 1567-214x. Keywords: Freedom of belief and religion,activities of beliefs and religious, policies of Vietnam. ABSTRACT: Currently, the right to freedom of religion and belief in Vietnam is always guaranteed and improved increasingly according to the development trend of the country and the general trend of the times. In Vietnam today, it is quite vibrant and diverse with many different forms of belief and religious activities, many different religious organizations and organizational models. The establishment of religious organizations reflects the State’s concern in the consistent exercise of the right to freedom of belief and religion, and affirms that Vietnam does not distinguish between people of beliefs or are not; does not discriminate against or discriminate against any religion, whether endogenous or transmitted from abroad, whether it is a religion that has long-term stability or has just been recognized. This study focuses on analyzing the activity of belief, religion as well as religious policy in Vietnam today. From there, raising the awareness of people about activity of the beliefs, religions and religious policies of Vietnam. -

New Religions in Global Perspective

New Religions in Global Perspective New Religions in Global Perspective is a fresh in-depth account of new religious movements, and of new forms of spirituality from a global vantage point. Ranging from North America and Europe to Japan, Latin America, South Asia, Africa and the Caribbean, this book provides students with a complete introduction to NRMs such as Falun Gong, Aum Shinrikyo, the Brahma Kumaris movement, the Ikhwan or Muslim Brotherhood, Sufism, the Engaged Buddhist and Neo-Hindu movements, Messianic Judaism, and African diaspora movements including Rastafarianism. Peter Clarke explores the innovative character of new religious movements, charting their cultural significance and global impact, and how various religious traditions are shaping, rather than displacing, each other’s understanding of notions such as transcendence and faith, good and evil, of the meaning, purpose and function of religion, and of religious belonging. In addition to exploring the responses of governments, churches, the media and general public to new religious movements, Clarke examines the reactions to older, increasingly influential religions, such as Buddhism and Islam, in new geographical and cultural contexts. Taking into account the degree of continuity between old and new religions, each chapter contains not only an account of the rise of the NRMs and new forms of spirituality in a particular region, but also an overview of change in the regions’ mainstream religions. Peter Clarke is Professor Emeritus of the History and Sociology of Religion at King’s College, University of London, and a professorial member of the Faculty of Theology, University of Oxford. Among his publications are (with Peter Byrne) Religion Defined and Explained (1993) and Japanese New Religions: In Global Perspective (ed.) (2000). -

9789004226487.Pdf

Handbook of New Religions and Cultural Production Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion Series Editors Carole M. Cusack, University of Sydney James R. Lewis, University of Tromsø Editorial Board Olav Hammer, University of Southern Denmark Charlotte Hardman, University of Durham Titus Hjelm, University College London Adam Possamai, University of Western Sydney Inken Prohl, University of Heidelberg VOLUME 4 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.nl/bhcr Handbook of New Religions and Cultural Production Edited by Carole M. Cusack and Alex Norman LEIDEN • BOSTON 2012 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Handbook of new religions and cultural production / edited by Carole M. Cusack and Alex Norman. p. cm. — (Brill handbooks on contemporary religion, ISSN 1874–6691 ; v. 4) Includes index. ISBN 978-90-04-22187-1 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Religion and culture. I. Cusack, Carole M., 1962– II. Norman, Alex. BL65.C8H365 2012 200.9’04—dc23 2011052361 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.nl/brill-typeface. ISSN 1874-6691 ISBN 978 90 04 22187 1 (hardback) ISBN 978 90 04 22648 7 (e-book) Copyright 2012 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers and Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. -

Vietnam Business Guide

HELPING YOUR BUSINESS GROW INTERNATIONALLY Vietnam Business Guide 1 This guide was produced by the UK Trade & Investment Vietnam Markets Unit in collaboration with the British Posts in Vietnam, international trade teams and the British Business Group Vietnam. Disclaimer Whereas every effort has been made to ensure that the information given in this document is accurate, neither UK Trade & Investment nor its parent Departments (the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office) accept liability for any errors, omissions or misleading statements, and no warranty is given or responsibility accepted as to the standing of any individual, firm, company or other organisation mentioned. 2 Front cover image: Ho Chi Minh City CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Why Vietnam? 4 About this Business Guide 13 RESEARCHING THE MARKET Where to begin 14 How we can help you 17 MARKET ENTRY Choosing the right location 21 Establishing a presence 24 GETTING STARTED Finding a customer or partner 31 Due diligence 32 Employing staff 33 Language 37 Marketing 38 Day-to-day communications 41 Interpreters 42 BUSINESS ISSUES AND Business etiquette 45 CONSIDERATIONS Intellectual property rights (IPR) 47 The Vietnamese legal system 48 Procurement 49 Regulations and standards 50 Getting paid and financial issues 56 Insurance 58 Management control and quality assurance 59 Bribery and corruption 60 Getting to Vietnam 61 VIETNAMESE CULTURE Politics 63 Current economic situation 64 Religion 65 Challenges 67 UK SUCCESS STORIES 68 CONTACTS 69 3 INTRODUCTION WHY VIETNAM? Vietnam has one of the fastest-growing, most vibrant economies in Asia. Over the past ten years, economic growth has been second only to China and GDP has been doubling every ten years since 1986. -

A Study on Religion

A Study on Religion Religious studies is the academic field of multi-disciplinary, secular study of religious beliefs, behaviors, and institutions. It describes, compares, interprets, and explains religion, emphasizing systematic, historically based, and cross-cultural perspectives. While theology attempts to understand the nature of transcendent or supernatural forces (such as deities), religious studies tries to study religious behavior and belief from outside any particular religious viewpoint. Religious studies draws upon multiple disciplines and their methodologies including anthropology, sociology, psychology, philosophy, and history of religion. Religious studies originated in the nineteenth century, when scholarly and historical analysis of the Bible had flourished, and Hindu and Buddhist texts were first being translated into European languages. Early influential scholars included Friedrich Max Müller, in England, and Cornelius P. Tiele, in the Netherlands. Today religious studies is practiced by scholars worldwide. In its early years, it was known as Comparative Religion or the Science of Religion and, in the USA, there are those who today also know the field as the History of religion (associated with methodological traditions traced to the University of Chicago in general, and in particular Mircea Eliade, from the late 1950s through to the late 1980s). The field is known as Religionswissenschaft in Germany and Sciences de la religion in the French-speaking world. The term "religion" originated from the Latin noun "religio", that was nominalized from one of three verbs: "relegere" (to turn to constantly/observe conscientiously); "religare" (to bind oneself [back]); and "reeligare" (to choose again).[1] Because of these three different meanings, an etymological analysis alone does not resolve the ambiguity of defining religion, since each verb points to a different understanding of what religion is.[2] During the Medieval Period, the term "religious" was used as a noun to describe someone who had joined a monastic order (a "religious"). -

Conceptual Structures of Vietnamese Emotions Hien T

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Linguistics ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Summer 7-15-2018 Conceptual Structures of Vietnamese Emotions Hien T. Tran University of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ling_etds Part of the Linguistics Commons Recommended Citation Tran, Hien T.. "Conceptual Structures of Vietnamese Emotions." (2018). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ling_etds/58 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Linguistics ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hien Thi Tran Candidate Linguistics Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. Melissa Axelrod, Chairperson Dr. Sherman Wilcox Dr. Phyllis Perrin Wilcox Dr. Zouhair Maalej CONCEPTUAL STRUCTURES OF VIETNAMESE EMOTIONS by HIEN THI TRAN B.A., Linguistics, Hanoi University, 1996 M.A., Linguistics, University of New Mexico, 2007 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Linguistics The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico July 2018 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank many people for their support and encouragement during my academic studies at the University of New Mexico. I am always grateful to Dr. Melissa Axelrod, my dissertation committee chair for her consistent inspiration, encouragement and guidance which helped me to complete this work. Dr. Axelrod is an exemplary professor. I consider myself very fortunate to have had her as my dissertation committee chair. -

Hoskins, Janet

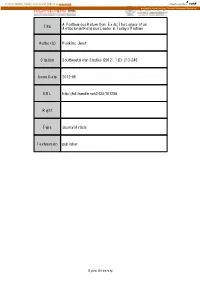

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository A Posthumous Return from Exile: The Legacy of an Title Anticolonial Religious Leader in Today's Vietnam Author(s) Hoskins, Janet Citation Southeast Asian Studies (2012), 1(2): 213-246 Issue Date 2012-08 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/167298 Right Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University A Posthumous Return from Exile: The Legacy of an Anticolonial Religious Leader in Today’s Vietnam Janet Hoskins* The 2006 return of the body Phạm Công Tắc, one of the founding spirit mediums of Caodaism and its most famous 20th century leader, re-awakened controversies about his life and legacy among Caodaists both in Vietnam and in the diaspora. This paper argues that his most important contribution lay in formulating a utopian project to support the struggle for independence by providing a religiously based repertoire of concepts to imagine national autonomy, and a separate apparatus of power to achieve it. Rather than stressing Tắc’s political actions, which have been well documented in earlier studies (Blagov 2001; Bernard Fall 1955; Werner 1976), I focus instead on a reading of his sermons, his séance transcripts and commentaries, histories published both in Vietnam and in the diaspora, and conversations with Caodaists in several countries when the appropriateness of returning his body was being debated. Keywords: Vietnamese religion, anti-colonial struggle, diaspora, postcolonial theory On November 1, 2006, excited crowds in Tây Ninh gathered in front of the huge central gate to their sacred city, which had not been opened for half a century. -

What Are Vietnam's Indigenous Religions?

No.64 Autumn 2011 What Are Vietnam’s Indigenous Religions? Janet Hoskins ........................................................................................ 3 Does Popular Culture Matter to the Southeast Asian Region? Possible Implications and Methodological Challenges Nissim Otmazgin ................................................................................... 7 Seeing Genocide and Reconciliation in Cambodia through a Village Kobayashi Satoru ................................................................................. 11 Exploring Urban Transformation of Hanoi in the French Colonial Period: An Area Informatics Approach Shibayama Mamoru ............................................................................. 13 !"#$%&'()$*+,+-#(.$'/$0'1,234$5#]#7,+'(.$'($8+932(,$:'3;#3 Spaces and Expressions of Community and Agency Aya Fabros ............................................................................................ 16 <(='(#.+2($>#12?#$8+932(,$:'3;#3.$2(=$,"#+3$&2332,+@#. Jafar Suryomenggolo ............................................................................ 20 The “Baybayin Stones” of Ticao, Masbate (Philippines) Ramon Guillermo ................................................................................. 22 *2.+('.$+($A'3=#3$!'B(.$+($,"#$8#;'(9$CDEF5#9+'( Thanyathip Sripana ..............................................................................25 G,"$0H','$I(+@#3.+,H$C'D,"#2.,$J.+2($>'3D1$2(= KU Japanese Alumni Association Mario Lopez .........................................................................................