A Brief Comparison of God, Revelation, and Morality in Caodaism and Oomoto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Invention Of

How Did God Get Started? COLIN WELLS the usual suspects One day in the Middle East about four thousand years ago, an elderly but still rather astonishingly spry gentleman took his son for a walk up a hill. The young man carried on his back some wood that his father had told him they would use at the top to make an altar, upon which they would then perform the ritual sacrifice of a burnt offering. Unbeknownst to the son, however, the father had another sort of sacrifice in mind altogether. Abraham, the father, had been commanded, by the God he worshipped as supreme above all others, to sacrifice the young man himself, his beloved and only legitimate son, Isaac. We all know how things turned out, of course. An angel appeared, together with a ram, letting Abraham know that God didn’t really want him to kill his son, that he should sacrifice the ram instead, and that the whole thing had merely been a test. And to modern observers, at least, it’s abundantly clear what exactly was being tested. Should we pose the question to most people familiar with one of the three “Abrahamic” religious traditions (Judaism, Christianity, Islam), all of which trace their origins to this misty figure, and which together claim half the world’s population, the answer would come without hesitation. God was testing Abraham’s faith. If we could ask someone from a much earlier time, however, a time closer to that of Abraham himself, the answer might be different. The usual story we tell ourselves about faith and reason says that faith was invented by the ancient Jews, whose monotheistic tradition goes back to Abraham. -

I. the Word of God Is Everything We Need II. God Has Given Us

What people need to understand today is that the truth is important. What you beLieve to be true is important, because it wiLL determine how you see Life and how you Live your Life. It wiLL determine your abiLity to understand Life and obey God. Truth exists because God is trustworthy. The biblical understanding of truth is that all truth comes from God. God has breathed life into all of Scripture. It is useful for teaching us The entirety of Your word is truth, and every one of Your what is true. It is useful for correcting our mistakes. It is useful for righteous judgments endures forever. PsaLm 119:160 making our lives whole again. It is useful for training us to do what is right. By using Scripture, a man of God can be completely prepared Truth is a gift that God gives to mankind. As we honor that to do every good thing. 2 Timothy 3:16-17 NIRV truth by believing in it and living by it we are blessed and preserved because of it. I. The Word of God is Everything We Need 4. God’s Word is to be obeyed as God directLy telling us what to do. It has been written, Man shall not live and be upheld and sustained by bread alone, but by every word that comes forth from the mouth of When God commands, we are to obey. When he asserts, we are God. Matthew 4:4 (AMP) to believe Him. When he promises, we are to embrace and trust those promises; thus, we respond to the sheer authority of For the Christian, the Bible is the measuring rod, and final word God’s word. -

Experiencing God: God Speaks by the Holy Spirit Through Bible and Prayer

• OCTOBER 5 • EXPERIENCING GOD: GOD SPEAKS BY THE HOLY SPIRIT THROUGH BIBLE AND PRAYER Reality #4: God speaks by the Holy Spirit through the Bible, prayer, circumstances, and the church to reveal Himself, His purposes, and His ways. Hebrews 1:1, “Long ago, at many times and in many ways, God spoke to our fathers by the prophets…” When God spoke: 1. It was usually unique to that individual 2. He gave enough specific directions to do something now (Exodus 3:16-22) God speaks by the Holy Spirit 1 Corinthians 3:16, “Do you not know that you are God’s temple and that God’s Spirit dwells in you?” John 14:26, “But the Helper, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, he will teach you all things and bring to your remembrance all that I have said to you.” John 16:13-14, “When the Spirit of truth comes, he will guide you into all the truth, for he will not speak on his own authority, but whatever he hears he will speak, and he will declare to you the things that are to come. He will glorify me, for he will take what is mine and declare it to you.” 1. God reveals Himself - because He wants you to have faith to believe He can do what He says. Leviticus 19:1-2, “And the Lord spoke to Moses, saying, ‘Speak to all the congregation of the people of Israel and say to them, You shall be holy, for I the Lord your God am holy.’” 2. -

Brahman, Atman and Maya

Sanatana Dharma The Eternal Way of Life (Hinduism) Brahman, Atman and Maya The Hindu Way of Comprehending Reality and Life Brahman, Atman and Maya u These three terms are essential in understanding the Hindu view of reality. v Brahman—that which gives rise to maya v Atman—what each maya truly is v Maya—appearances of Brahman (all the phenomena in the cosmos) Early Vedic Deities u The Aryan people worship many deities through sacrificial rituals: v Agni—the god of fire v Indra—the god of thunder, a warrior god v Varuna—the god of cosmic order (rita) v Surya—the sun god v Ushas—the goddess of dawn v Rudra—the storm god v Yama—the first mortal to die and become the ruler of the afterworld The Meaning of Sacrificial Rituals u Why worship deities? u During the period of Upanishads, Hindus began to search for the deeper meaning of sacrificial rituals. u Hindus came to realize that presenting offerings to deities and asking favors in return are self-serving. u The focus gradually shifted to the offerings (the sacrificed). u The sacrificed symbolizes forgoing one’s well-being for the sake of the well- being of others. This understanding became the foundation of Hindu spirituality. In the old rites, the patron had passed the burden of death on to others. By accepting his invitation to the sacrificial banquet, the guests had to take responsibility for the death of the animal victim. In the new rite, the sacrificer made himself accountable for the death of the beast. -

Integrating Việt Nam Into World History Surveys

Southeast Asia in the Humanities and Social Science Curricula Integrating Việt Nam into World History Surveys By Mauricio Borrero and Tuan A. To t is not an exaggeration to say that the Việt Nam War of the 1960–70s emphasize to help students navigate the long span of world history surveys. remains the major, and sometimes only, point of entry of Việt Nam Another reason why world history teachers are often inclined to teach into the American imagination. Tis is true for popular culture in Việt Nam solely in the context of war is the abundance of teaching aids general and the classroom in particular. Although the Việt Nam War centered on the Việt Nam War. There is a large body of films and docu- ended almost forty years ago, American high school and college stu- mentaries about the war. Many of these films feature popular American dents continue to learn about Việt Nam mostly as a war and not as a coun- actors such as Sylvester Stallone, Tom Berenger, and Tom Cruise. There Itry. Whatever coverage of Việt Nam found in history textbooks is primar- are also a large number of games and songs about the war, as well as sub- ily devoted to the war. Beyond the classroom, most materials about Việt stantial news coverage of veterans and the Việt Nam War whenever the Nam available to students and the general public, such as news, literature, United States engages militarily in any part of the world. American lit- games, and movies, are also related to the war. Learning about Việt Nam as erature, too, has a large selection of memoirs, diaries, history books, and a war keeps students from a holistic understanding of a thriving country of novels about the war. -

Gods and Myths: Creation of the World

01/12/2016 Gods and Myths: Creation of the World 1 01/12/2016 Ancient Cosmology ‐ What was the shape of the Universe imaged by those ancient peoples to whom all modern knowledge of geography and astronomy was inacessible ? ‐ How did they conceive the form of the cosmos which accommodated not only the known face of the earth and the visible heavenly bodies, but also those other worlds ie. the realms of the dead, both blessed and damned, and the countries inhabited by gods and demons ? • In some cosmologies space inseparable from time : ‐ no account of the shape of the universe would make sense unless we know how it came to be so in the first place ‐ in other words, the cosmologies go along with creation myths ie. the creation of the universe is an essential feature of cosmology ‐ uniquely, this lead the Jewish (biblical and rabbinical) sources to the solution of a notion of linear time ‐ by contrast: • China: notion of creation not of prime importance • Greeks: not so interested in beginnings • Jains: uninterested in beginnings • India: time scales as vast as space, leading to the notion of cyclical time • Norse/Greeks/Chines: also cyclical time notion • 2 01/12/2016 Religious Cosmology ‐ A Way of explaining the Origin, History and Evolution of the Cosmos or Universe on the Religious Mythology of a specific tradition. ‐ Religious cosmologies usually include an act or process of creation by a creator deity or pantheon Creation Myth ‐ A symbolic narrative of how the world began and how people first became to inhabit it. -

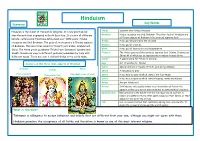

Hinduism Summary Key Words

Hinduism Summary Key Words Hindu Someone who follows Hinduism. Hinduism is the oldest of the world’s religions. It is now practised all over the world but originated in South East Asia. It is a mix of different Brahman Hindus recognise one God, Brahman. The other Gods of Hinduism are different aspects of Brahman (The universal supreme God) beliefs, cultures and traditions dating back over 4000 years. Hindus Vishnu Hindu god who protects the universe. recognise one God, Brahman. The gods of Hinduism are different aspects Brahma Hindu god of creation. of Brahman. The main three aspects (Trimurti) are Vishnu, Brahma and Shiva. The three great goddesses (Tridevi) are Saraswati, Lakshmi and Shiva Hindu god of destruction and regeneration Shakti. Hindus can pray to different gods and goddesses for help with Trimurti The three aspects of the universal supreme God. (Vishnu, Brahma and Shiva) All of which can be represented in male or female forms. different needs. There are over 1.1 billion Hindus in the world today. mandir A special place for Hindus to worship. Avatars of the three main aspects of Brahman puja Act of worship for Hindus. murtis Special statues or images of Hindu gods and goddesses. Brahma Shiva Vishnu shrine A holy place to pray. (the creator) (the protector) (the destroyer of evil) Shruti Hindu holy scriptures which contain the four Vedas. Smriti Hindu holy scriptures which contain legends, myths and history. Vedas Ancient Hindu text. Avatar In Hinduism, this usually refers to an incarnation of God or His aspects, either as a man or even an animal or some mythical creature. -

Conceptualizations of God by Lutheran Laypeople Ashley Burgess Leininger Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2009 Conceptualizations of God by Lutheran laypeople Ashley Burgess Leininger Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Leininger, Ashley Burgess, "Conceptualizations of God by Lutheran laypeople" (2009). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 10805. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/10805 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Conceptualizations of God by Lutheran laypeople by Ashley Burgess Leininger A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Sociology Program of Study Committee: David Schweingruber, Major Professor Gloria Jones-Johnson Carl Roberts Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2009 Copyright © Ashley Burgess Leininger, 2009. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................. iv ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................ v INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. -

God Is the Gospel the Glory of God in the Face of Jesus 1 God God

God God God, God God God God Is the Gospel The Glory of God in the Face of Jesus 1 God God. God God God God This book is a plea that God himself, as revealed most clearly t and fully in Jesus’s death and resurrection, be seen and en- God God God God God God. joyed as the final and greatest gift of the gospel. 2 The gospel of Jesus and his many precious blessings are not God God God God God God ultimately what makes the good news good, but means of seeing and savoring the Savior himself. Forgiveness is good because it opens the way to enjoying God himself. Justification God God God God God is good because it wins access to the presence and pleasure of God himself. Eternal life is good because it becomes the ever- u lasting enjoyment of Jesus. God Is the Gospel God God, All God’s good gifts are loving to the degree that they lead us to God himself. This is the love of God: doing everything neces- God God God God God God God sary, most painfully in the death of his Son, to enthrall us with what is most deeply and durably satisfying—namely, himself. God God God God. God God JOHN PIPER is pastor for preaching and vision at Bethlehem Piper Baptist Church in Minneapolis. He has authored numerous books, God God God God?” God God including Desiring God, Don’t Waste Your Life, This Momentary Marriage, and Think. 4God God God, God God God u Meditations on God’s Love as the Gift of Himself CHRISTIAN LIVING John Piper God Is the Gospel Copyright © 2005 by Desiring God Foundation Published by Crossway 1300 Crescent Street Wheaton, Illinois 60187 All rights reserved. -

Narratives of Identity and Adaptation from Persian Baha'i Refugees in Australia

Ahliat va Masir (Roots and Routes) Narratives of identity and adaptation from Persian Baha'i refugees in Australia. Ruth Williams Bachelor of Arts (Monash University) Bachelor of Teaching (Hons) (University of Melbourne) This thesis is submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Behavioural and Social Sciences and Humanities University of Ballarat, PO Box 663, University Drive, Mount Helen, Ballarat, Victoria, 3353, Australia Submitted for examination in December 2008. 1 Abstract This study aims to discover what oral history narratives reveal about the post- migration renegotiation of identity for seven Persian Baha'i refugees and to assess the ensuing impact on their adaptation to Australia. Oral history interviewing was used as the methodology in this research and a four-part model of narrative classification was employed to analyse the oral history interviews. This small-scale, case study research offers in-depth insights into the process of cross- cultural renegotiation of identities and of adaptation to new situations of a group who do not reflect the generally negative outcomes of refugees. Such a method fosters greater understanding and sensitivity than may be possible in broad, quantitative studies. This research reveals the centrality of religion to the participants' cosmopolitan and hybrid identities. The Baha'i belief system facilitates the reidentification and adaptation processes through advocating such aspects as intermarriage and dispersal amongst the population. The dual themes of separateness and belonging; continuity and change; and communion and agency also have considerable heuristic value in understanding the renegotiation of identity and adaptation. Participants demonstrate qualities of agency by becoming empowered, self-made individuals, who are represented in well-paid occupations with high status qualifications. -

Dr. Roy Murphy

US THE WHO, WHAT & WHY OF MANKIND Dr. Roy Murphy Visit us online at arbium.com An Arbium Publishing Production Copyright © Dr. Roy Murphy 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the copyright owner. Nor can it be circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without similar condition including this condition being imposed on a subsequent purchaser. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Cover design created by Mike Peers Visit online at www.mikepeers.com First Edition – 2013 ISBN 978-0-9576845-0-8 eBook-Kindle ISBN 978-0-9576845-1-5 eBook-PDF Arbium Publishing The Coach House 7, The Manor Moreton Pinkney Northamptonshire NN11 3SJ United Kingdom Printed in the United Kingdom Vi Veri Veniversum Vivus Vici 863233150197864103023970580457627352658564321742494688920065350330360792390 084562153948658394270318956511426943949625100165706930700026073039838763165 193428338475410825583245389904994680203886845971940464531120110441936803512 987300644220801089521452145214347132059788963572089764615613235162105152978 885954490531552216832233086386968913700056669227507586411556656820982860701 449731015636154727292658469929507863512149404380292309794896331535736318924 980645663415740757239409987619164078746336039968042012469535859306751299283 295593697506027137110435364870426383781188694654021774469052574773074190283 -

The Word of God Or the Word of Man? 1 Thessalonians 2:13

MSJ 26/2 (Fall 2015) 179–202 THE WORD OF GOD OR THE WORD OF MAN? 1 THESSALONIANS 2:13 Gregory H. Harris Professor of Bible Exposition The Master’s Seminary First Thessalonians 2:13 separates and distinguishes between the Word of God and the word of man. Such doctrine is not a biblical mystery; neither its origin nor terminus occur in 1 Thess 2:13. Also, the reception and continued working of God’s holy Word in the lives of the Thessalonian believers gave clear indication that they qualified as “the good soil,” of which Jesus had taught. * * * * * Introduction The question of what is or what is not God’s Word has instigated an age-old theological battle going all the way back to creation. Genesis 1 contains eleven times some form of “And God said” (Gen 1:3, 6, 9, 11, 14, 20, 22, 24, 26, 28, 29).1 Genesis 2 adds two more such references, “and the LORD God commanded the man, saying” (2:16), and 2:18, “Then the LORD God said . .” Thus, thirteen times in the first two chapters, Genesis presents God as actively saying,2 and in this context, also sets forth the efficacious nature of God’s spoken word.3 The Bible presents Him as God alone 1 Unless otherwise stipulated, all Scripture references used are from the NASB 1977 edition. “Thee” and “Thou” are changed throughout to modern usage. 2 In reference to the repeated use and striking nature of this phrase in Gen 1:3, 6, 9, 11, 14, 20, 24, 26, 28, 29, Wenham states, “Though it is of course taken for granted throughout the OT that God speaks, to say” is used here in a more pregnant sense than usual.