Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Example from the Amoco Cadiz Oil Spill

THE IMPORTANCE OF USING APPROPRIATE EXPERIMENTAL DESIGNS IN OIL SPILL IMPACT STUDIES: AN EXAMPLE FROM THE AMOCO CADIZ OIL SPILL IMPACT ZONE Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/iosc/article-pdf/1987/1/503/2349658/2169-3358-1987-1-503.pdf by guest on 27 September 2021 Edward S. Gilfillan, David S. Page, Barbara Griffin, Sherry A. Hanson, Judith C. Foster Bowdoin College Marine Research Laboratory and Bowdoin College Hydrocarbon Research Center Brunswick, Maine 04011 ABSTRACT: On March 16, 1978, the tanker Amoco Cadiz ran factors as possible in a sampling program to look at oil spill effects. aground off the coast of North Brittany. Her cargo of 221,000 tons of When using non-specific stress responses, it is important to be sure light crude oil was released into the sea. More than 126 miles of coast- just which Stressors are producing any observed responses. Multi- line were oiled, including a number of oyster (Crassostrea gigas j grow- variate statistical methods appear to be useful in associating body ing establishments. The North Brittany coastline already was stressed burdens of multiple Stressors with observed physiological effects. by earlier additions of oil and metals. In a field study by Gilfillan et al.,6 it was shown, using multivariate In December 1979, 21 months after the oil spill, measurements of techniques, that in populations of Mytilus edulis from a moderately glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity, aspartate aminotransfer- polluted estuary the animals were responding to Cu, Cr, and Cd at the ase activity, and condition index were made in 14 populations of C. -

Admiralty, Maritime & Naval

30 ANTIQUARIAN TITLES ON ADMIRALTY, MARITIME & NAVAL LAW May 10, 2016 The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. (800) 422-6686 or (732) 382-1800 | Fax: (732) 382-1887 [email protected] | www.lawbookexchange.com 30 Antiquarian Titles on Admiralty, Maritime and Naval Law Scarce Eighteenth-Century Treatise on Prize Law and Privateering 1. Abreu y Bertodano, Felix Joseph de [c.1700-1775]. Traite Juridico-Politique sur les Prises Maritimes, et Sur les Moyens qui Doivent Concourir pour Rendre ces Prises Legitimes. Paris: Chez la Veuve Delaguette, 1758. Two volumes in one, each with title page and individual pagination. Octavo (6-1/2" x 4"). Contemporary speckled sheep, raised bands, lettering piece and gilt ornaments to spine, speckled edges, patterned endpapers. Some wear to corners, joints starting, some worming to lettering piece, joints and hinges. Attractive woodcut head-pieces. Toning to sections of text, light foxing to a few leaves, internally clean. An appealing copy of a scarce title. $1,500. * Second French edition. First published in Madrid in 1746, this treatise on prize law and privateering went through three other editions, all in France in a translation by the author, in 1753, 1758 and 1802. Little is known about Abreu, a minor Spanish noble and diplomat. According to the title page, he was a "membre de l'Academie Espagnole, & actuellement Envoye Extraordinaire de S.M. Catholique aupres du Roi de la Grande-Bretagne." All editions are scarce. OCLC locates 5 copies of all editions in the Americas, 1 of this edition (at Columbia University Law Library). Not in the British Museum Catalogue. -

A Comparative History of Insurance Law in Europe. a Research Agenda

Comparative Studies in the History of Insurance Law Studien zur vergleichenden Geschichte des Versicherungsrechts Volume / Band 1 A Comparative History of Insurance Law in Europe A Research Agenda Edited by Phillip Hellwege Duncker & Humblot · Berlin PHILLIP HELLWEGE (ED.) A Comparative History of Insurance Law in Europe Comparative Studies in the History of Insurance Law Studien zur vergleichenden Geschichte des Versicherungsrechts Edited by / Herausgegeben von Prof. Dr. Phillip Hellwege Volume / Band 1 A Comparative History of Insurance Law in Europe A Research Agenda Edited by Phillip Hellwege Duncker & Humblot · Berlin The project ‘A Comparative History of Insurance Law in Europe’ has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 647019). Bibliographic information of the German national library The German national library registers this publication in the German national bibliography; specified bibliographic data are retrievable on the Internet about http://dnb.d-nb.de. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, translated, or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without the expressed written consent of the publisher. © 2018 Duncker & Humblot GmbH, Berlin Printing: CPI buchbücher.de GmbH, Birkach Printed in Germany ISSN 2625-638X (Print) / ISSN 2625-6398 (Online) ISBN 978-3-428-15499-9 (Print) ISBN 978-3-428-55499-7 (E-Book) ISBN 978-3-428-85499-8 (Print & E-Book) Printed on no aging resistant (non-acid) paper according to ISO 9706 Internet: http://www.duncker-humblot.de Preface The history of insurance law has fallen into neglect, and the state of research is for a number of reasons unsatisfactory. -

Principles of Insurance Law Peter N

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2011 Principles of Insurance Law Peter N. Swisher University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/law-faculty-publications Part of the Insurance Law Commons Recommended Citation Jeffrey W. Stempel et al., Principles of Insurance Law (4th ed., 2011). This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRINCIPLES OF INSURANCE LAW FOURTH EDITION JEFFREY W. STEMPEL Doris S. & Theodore B. Lee Professor of Law William S. Boyd School of Law University of Nevada, Las Vegas PETER N. SWISHER Professor of Law T.C. Williams School of Law University of Richmond ERIK S. KNUTSEN Associate Professor Queen's University Faculty of Law Kingston, Ontario, Canada • . LexisNexis· Preface There have been a number of important developments in liability insurance, property insurance, and life and health insurance that have significantly impacted insurance law. Accordingly, our Fourth Edition of Principles of Insurance Law has been substantially revised and updated in order to offer the insurance law student and practitioner a broad perspective of both traditional insurance law concepts and cutting-edge legal issues affecting contemporary insurance law theory and practice. We have retained .the organization substantially begun in the Third Edition, with fifteen chapters, a division that enables an expanded scope of topical coverage and also segments the law of insurance in a manner more amenable to study, as well as facilitating recombination and reordering of the chapters as desired by individual instructors. -

Taxation of Insurance Companies

Taxation of Insurance Companies Informational Paper 10 Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau January, 2017 Taxation of Insurance Companies Prepared by Sean Moran Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau One East Main, Suite 301 Madison, WI 53703 http://legis.wisconsin.gov/lfb Taxation of Insurance Companies This paper provides background information example, under a pure "term" life insurance on the taxation of insurance companies in policy, the insured pays a premium which Wisconsin. While the main topic is the separate obligates the insurance company to pay a specific state premiums tax imposed on certain insurance sum in the event of the insured's death during the companies, the imposition of the state corporate term of the policy. Term insurance is the most income/franchise tax is also discussed. straightforward type of life insurance policy in that the premium provides coverage only in the In order to put the taxation of insurance com- event of death during the policy's specified term. panies in focus, information is provided on the characteristics of the insurance industry and the Certain life insurance policies perform a bank- Wisconsin operations of some of the major com- like function in that policyholder premiums are panies in different lines of insurance. The regula- invested by the insurer on behalf of the insured. tory role of the Office of the Commissioner of Income from such investments is credited to the Insurance (OCI) is also discussed briefly. Finally, policyholder's account in determining the policy's a discussion of the rationale and issues of insur- "cash surrender value," which is the amount which ance taxation is presented and the insurance tax the insured would receive if he or she cancels the provisions of other states are outlined. -

States of Emergency

STATES OF EMERGENCY Technological Failures and Social Destabilization Patrick Lagadec Contents Introduction PART ONE Technical Breakdown, Crisis and Destabilization Framework of Reference 1. The weapons of crisis ........................................................................................ 11 1. An unusual event in a metastable context .......................................................... 12 2. Crisis dynamics................................................................................................... 21 2. Organizations with their backs to the wall...................................................... 23 1. Classic destabilization scenarios ......................................................................... 24 2. Slipping out of control ....................................................................................... 35 PART TWO Technological Crisis and the Actors Involved 3- In the thick of things ....................................................................................... 43 - Marc Becam ....................................................................................................... 45 The oil spill from the "Amoco Cadiz", March - May, 1978 - Richard Thornburgh........................................................................................... 55 Three Mile Island, March - April, 1979 - Douglas K. Burrows .......................................................................................... 66 The great Mississauga evacuation, November 10-16. 1979 - Péter-J.Hargitay .............................................................................................. -

The Oil Pollution Act of 1990: Reaction and Response

Volume 3 Issue 2 Article 2 1992 The Oil Pollution Act of 1990: Reaction and Response Michael P. Donaldson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/elj Part of the Environmental Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael P. Donaldson, The Oil Pollution Act of 1990: Reaction and Response, 3 Vill. Envtl. L.J. 283 (1992). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/elj/vol3/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Villanova Environmental Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Donaldson: The Oil Pollution Act of 1990: Reaction and Response 19921 THE OIL POLLUTION ACT OF 1990: REACTION AND RESPONSE MICHAEL P. DONALDSONt TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ....................................... 283 II. PRE-OPA OIL SPILL LIABILITY ..........................284 III. THE OIL POLLUTION ACT OF 1990 .................... 288 IV. PREVIOUSLY CONSIDERED APPROACHES ................ 301 A. International Liability and Compensation Conventions ..................................... 301 B. Approaches Suggested by Congress .............. 305 V. CONCERNS AND REACTIONS TO THE OIL POLLUTION ACT OF 1990 ............................................. 3 13 A. Reaction by Industry ............................ 313 B. International Reactions .......................... 317 VI. CONCLUSION ........................................ -

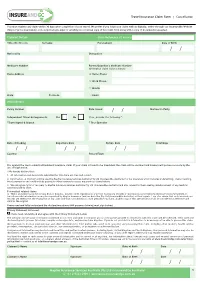

Cancellation Claim Form

Travel Insurance Claim Form | Cancellation You must register any claim within 30 days after completion of your travel. We prefer if you lodge your claim with us digitally, either through our InsureandGo Website (https://quote.insureandgo.com.au/policylogin.aspx) or emailing us a scanned copy of this claim form along with a copy of documents requested. Claimant Details Claim Reference (if known) Title (Mr/Mrs etc) Surname Forename(s) Date of Birth / / Nationality Occupation Medicare Number Parent/Guardian’s Medicare Number (If medical claim is for a minor) Home Address ' Home Phone ' Work Phone ' Mobile State Postcode Email Policy Details Policy Number Date Issued / / Number in Party Independent Travel Arrangements: Yes No If no, provide the following *: *Travel Agent & Branch * Tour Operator Date of Booking Departure Date Return Date Total Days / / / / / / Country Resort/Town It is against the law to submit a fraudulent insurance claim. If your claim is found to be fraudulent the claim will be declined and Insurers will pursue recovery by the use of legal action. I/We hereby declare that: 1. All information and documents submitted for this claim are true and correct. 2. Information on this form will be used by Mapfre Insurance Services Australia Pty Ltd (InsureandGo Australia) for my insurance which includes underwriting, claims handling, fraud prevention and could include passing to other insurers to access my previous claims history. 3. We subrogate rights of recovery to Mapfre Insurance Services Australia Pty Ltd (InsureandGo Australia) and also consent to them seeking reimbursement of any medical expenses paid by them. For medical related claims: 4. -

Introduction to Insurance

Introduction To Insurance By Cathy Pareto http://www.investopedia.com/university/insurance/default.asp Thanks very much for downloading the printable version of this tutorial. As always, we welcome any feedback or suggestions. http://www.investopedia.com/contact.aspx Table of Contents 1) Intro To Insurance: Introduction 2) Intro To Insurance: What Is Insurance? 3) Intro To Insurance: Fundamentals Of Insurance 4) Intro To Insurance: Property And Casualty Insurance 5) Intro To Insurance: Health Insurance 6) Intro To Insurance: Disability Insurance 7) Intro To Insurance: Long-Term Care Insurance 8) Intro To Insurance: Life Insurance 9) Intro To Insurance: Types Of Life Insurance 10) Intro To Insurance: Life Insurance Considerations 11) Intro To Insurance: Other Insurance Policies 12) Intro To Insurance: Conclusion Introduction In one form or another, we all own insurance. Whether it's auto, medical, liability, disability or life, insurance serves as an excellent risk-management and wealth- preservation tool. Having the right kind of insurance is a critical component of any good financial plan. While most of us own insurance, many of us don't understand what it is or how it works. In this tutorial, we'll review the basics of insurance and how it works, then take you through the main types of insurance out there. (To read more about insurance, see our Special Insurance Feature.) What Is Insurance? Insurance is a form of risk management in which the insured transfers the cost of potential loss to another entity in exchange for monetary compensation known as the premium. (For background reading, see The History Of Insurance In (Page 1 of 29) Copyright © 2010, Investopedia.com - All rights reserved. -

Selected European Oil Spill Policies

Chapter 5 Selected European Oil Spill Policies INTRODUCTION authority to use whatever means are deemed most appropriate to fight the spill. Oil that In order to investigate oil spill technologies has reached the shoreline is the responsibility in use abroad and to learn how the United of local authorities. States might benefit from the oil spill experi- For fighting oil spills at sea, the offshore ences and policies of some other countries, area surrounding France has been divided OTA staff visited four countries bordering the into three maritime regions. Oil spill re- North Sea in September, 1989: France, the sponses within each region are directed by the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and Nor- responsible Maritime Prefect, a senior Navy way. OTA’s trip was coordinated by the Inter- officer who is also responsible for the defense national Petroleum Industry Environmental of the area.1 The Maritime Prefect’s first pri- Conservation Association and included visits ority is to prevent maritime accidents by en- to a number of government and industry or- forcing navigation regulations. Traffic separa- ganizations in these countries. The four coun- tion lanes have been established in some tries selected represent a wide range of tech- areas, and large, ocean-going tugs are used as nologies and countermeasures policies. Below both “watch dogs” and rescue ships. In the are some of the highlights of our findings. event of a spill, the Maritime Prefect func- tions as onscene commander rather than on- scene coordinator, and hence has considerably FRENCH OIL SPILL POLICY more authority than his U.S. Coast Guard counterpart. -

Travel Insurance Claim Form | Cruise Mapfre Insurance Services

Travel Insurance Claim Form | Cruise You must register any claim within 30 days after completion of your travel. We prefer if you lodge your claim with us digitally, either through our InsureandGo Website (https://quote.insureandgo.com.au/policylogin.aspx) or emailing us a scanned copy of this claim form along with a copy of documents requested. Claimant Details Claim Reference (if known) Title (Mr/Mrs etc) Surname Forename(s) Date of Birth / / Nationality Occupation Medicare Number Parent/Guardian’s Medicare Number (If medical claim is for a minor) Home Address ' Home Phone ' Work Phone ' Mobile State Postcode Email Policy Details Policy Number Date Issued / / Number in Party Independent Travel Arrangements: Yes No If no, provide the following *: *Travel Agent & Branch * Tour Operator Date of Booking Departure Date Return Date Total Days / / / / / / Country Resort/Town It is against the law to submit a fraudulent insurance claim. If your claim is found to be fraudulent the claim will be declined and Insurers will pursue recovery by the use of legal action. I/We hereby declare that: 1. All information and documents submitted for this claim are true and correct. 2. Information on this form will be used by Mapfre Insurance Services Australia Pty Ltd (InsureandGo Australia) for my insurance which includes underwriting, claims handling, fraud prevention and could include passing to other insurers to access my previous claims history. 3. We subrogate rights of recovery to Mapfre Insurance Services Australia Pty Ltd (InsureandGo Australia) and also consent to them seeking reimbursement of any medical expenses paid by them. For medical related claims: 4. -

Amoco Cadi2 Litigation: Summary of the 1988 Court Decision

Gundlach, E. R. (1989). Amoco Cadiz Litigation: Summary of the 1988 Court Decision. Proceedings of the 1989 Oil Spill Conference, Washington, D.C., American Petroleum Institute. 503-508. AMOCO CADI2 LITIGATION: SUMMARY OF THE 1988 COURT DECISION Erich R. Gundlach E-Tech Inc. 70 Dean Knalcss Drive Narragansett, Rhode Island 02882 ABSTRACT: In January 1988, Judge Frank McGarr of the United ment and Quality of Life. The commune consortium rcpmcntd States Dismct Coun in Chicago presented the decision concerning all a total of 90 communes located within, and adjacent to, the spill- claim by the French government, local communes, fisheries groups, affected area. The miscellaneous claim category consisted of &- and other pam'es, concerning the financial liability of the Amoco par- tively small suits brought by certain hotel owners, property owners, ties for damages related to the Amoco Cadi oil spill of March 1978. fishermen, and environmental associations. Several categories of claims, including lost image, lost enjoyment, and ecological &magi were eliminate8 as being uncognizable under French law. Claim for un~aidvolunteers who worked on thes~illwere also eliminated. ~dstothk categories were substantially reduced for a Summary of judgment: Republic of fiance variety of factors including exaggeration, lack of evidence, double billing of certain claims against Amoco Cadiz and the Tanio spill of two The Republic of France claim included a total of eight ministries years later, and the inability to attribute hmage directly to Amoco (Table 1). Claims for the ministries of Defense, Transportation, and Cadiz. Environment and Quality of Life represented more than 85 percent This paper summarizes the major claims and awards, and discusses of the total Republic of France claim and are discussed below.