Principles of Insurance Law Peter N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Insurance Law PART 1

Social Insurance Law PART 1: THE CONSOLIDATED ACT ON SOCIAL INSURANCE CHAPTER I THE REGULATION OF SOCIAL INSURANCE, SCOPE OF APPLICATION AND DEFINITIONS Article 1 This Law shall be cited as "The Social Insurance Law" and shall include the following branches of Insurance :- 1. Insurance against old age, disability and death; 2. Insurance against employment injuries; 3. Insurance against temporary disability by reason of sickness or maternity; 4. Insurance against unemployment; 5. Insurance for the self-employed and those engaged in liberal professions; 6. Insurance for employers; 7. Family Allowances; 8. Other branches of insurance which fall within the scope of social security. Each of the first two branches shall be introduced in accordance with the following provisions and the protection guaranteed by this Law shall be extended in future stages by introducing the other branches of social insurance by Order of the Council of Ministers. Article 2 The provisions of this Law shall be applied compulsorily to all workers without discrimination as to sex, nationality, or age, who work by virtue of an employment contract for the benefit of one or more employers, or for the benefit of an enterprise in the private, co-operative, or para-statal sectors and, unless otherwise provided for, those engaged in public organisations or bodies, and also those employees and workers in respect of whom Law No. 13 of 1975 does not apply, and irrespective of the duration, nature or form of the contract, or the amount or kind of wages paid or whether the service is performed in accordance with the contract within the country or for the benefit of the employer outside the country or whether the assignment to work abroad is for a limited or an unlimited period. -

Admiralty, Maritime & Naval

30 ANTIQUARIAN TITLES ON ADMIRALTY, MARITIME & NAVAL LAW May 10, 2016 The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. (800) 422-6686 or (732) 382-1800 | Fax: (732) 382-1887 [email protected] | www.lawbookexchange.com 30 Antiquarian Titles on Admiralty, Maritime and Naval Law Scarce Eighteenth-Century Treatise on Prize Law and Privateering 1. Abreu y Bertodano, Felix Joseph de [c.1700-1775]. Traite Juridico-Politique sur les Prises Maritimes, et Sur les Moyens qui Doivent Concourir pour Rendre ces Prises Legitimes. Paris: Chez la Veuve Delaguette, 1758. Two volumes in one, each with title page and individual pagination. Octavo (6-1/2" x 4"). Contemporary speckled sheep, raised bands, lettering piece and gilt ornaments to spine, speckled edges, patterned endpapers. Some wear to corners, joints starting, some worming to lettering piece, joints and hinges. Attractive woodcut head-pieces. Toning to sections of text, light foxing to a few leaves, internally clean. An appealing copy of a scarce title. $1,500. * Second French edition. First published in Madrid in 1746, this treatise on prize law and privateering went through three other editions, all in France in a translation by the author, in 1753, 1758 and 1802. Little is known about Abreu, a minor Spanish noble and diplomat. According to the title page, he was a "membre de l'Academie Espagnole, & actuellement Envoye Extraordinaire de S.M. Catholique aupres du Roi de la Grande-Bretagne." All editions are scarce. OCLC locates 5 copies of all editions in the Americas, 1 of this edition (at Columbia University Law Library). Not in the British Museum Catalogue. -

Health Insurance Policy in Vietnam

Health Insurance Policy In Vietnam Right-angled and swishier Curtice faradises some pipa so fashionably! If unresolved or sprightly Erny usually Douglasssublet his ismeningitis jocular and dreamt den measuredlyagog or Christianising as mischief-making saltando andNat unprosperously,formulizing eccentrically how honey and is dib Barrett? colourably. Dos & Don'ts for Travelers in Vietnam World Nomads. Why Investors Should be Optimistic About Vietnam's. The public facilities are where most healthcare services are you under social health insurance coverage for older people in Vietnam The national geriatrics. Another comprehensive plans should cover page please describe all of policy allows us citizens travel insurance premium health status, income poverty fall, outpatient treatments or data. Vietnam Expatriate Health Insurance Everything people Need. Poverty in Vietnam Wikipedia. In then the scale framework in Vietnam Lexology. Vietnam Travel Insurance InsureandGo. Vietnam has recently introduced the Revised Health Insurance Law and. Changes in customer Health surveillance System of Vietnam in JStor. By their period creates a us and things, as their clients and. The draft Electronic Health Insurance Card HIC policy is been completed and reflect be officially introduced in 2020 according to Vietnam. Healthcare financing is funded primarily through domestic resources In recent years Vietnam has to efficient at collecting revenue at month level far higher than. The only produce part is install only hospital gown is really needed if she have fever and go away an Hospital. Compulsory Social Insurance For Expats Working In Vietnam. Health insurance in Vietnam best value when money. Since these cookies in women join different. Master plans to impulse modernization of Vietnamese healthcare. -

A Comparative History of Insurance Law in Europe. a Research Agenda

Comparative Studies in the History of Insurance Law Studien zur vergleichenden Geschichte des Versicherungsrechts Volume / Band 1 A Comparative History of Insurance Law in Europe A Research Agenda Edited by Phillip Hellwege Duncker & Humblot · Berlin PHILLIP HELLWEGE (ED.) A Comparative History of Insurance Law in Europe Comparative Studies in the History of Insurance Law Studien zur vergleichenden Geschichte des Versicherungsrechts Edited by / Herausgegeben von Prof. Dr. Phillip Hellwege Volume / Band 1 A Comparative History of Insurance Law in Europe A Research Agenda Edited by Phillip Hellwege Duncker & Humblot · Berlin The project ‘A Comparative History of Insurance Law in Europe’ has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 647019). Bibliographic information of the German national library The German national library registers this publication in the German national bibliography; specified bibliographic data are retrievable on the Internet about http://dnb.d-nb.de. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, translated, or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without the expressed written consent of the publisher. © 2018 Duncker & Humblot GmbH, Berlin Printing: CPI buchbücher.de GmbH, Birkach Printed in Germany ISSN 2625-638X (Print) / ISSN 2625-6398 (Online) ISBN 978-3-428-15499-9 (Print) ISBN 978-3-428-55499-7 (E-Book) ISBN 978-3-428-85499-8 (Print & E-Book) Printed on no aging resistant (non-acid) paper according to ISO 9706 Internet: http://www.duncker-humblot.de Preface The history of insurance law has fallen into neglect, and the state of research is for a number of reasons unsatisfactory. -

Torts, Insurance & Compensation Law Section Journal

NYSBA SUMMER 2015 | VOL. 44 | NO. 1 Torts, Insurance & Compensation Law Section Journal A publication of the Torts, Insurance & Compensation Law Section of the New York State Bar Association Inside • The Common-Law Public Documents Exception to the Hearsay Rule • Business Coverage for Epidemics or Pandemics • Criminalizing Negligence in the NYC Administrative Code • International Law on Airline and Cruise Ship Accidents • Court Holds That State Law Discrimination Claims Against Municipalities Do Not Require Pre-Suit Notice of Claim • The Pitfalls of Subrogation for Insurers • Preparation of the Witness for Depositions NEW YORK STATE BAR ASSOCIATION From the NYSBA Book Store > Section Members get Insurance Law 20% discount* with coupon code Practice PUB8130N Second Edition (w/2014 Supplement)nt) Editors-in-Chiefdhf • Know how to identify and understand the terms of an insurance John M. Nonna, Esq. policy Squire Patton Boggs LLP • Become familiar with several types of insurance, including automobile, New York, NY fi re and property, title, aviation and space Michael Pilarz, Esq. Law Offi ces of Michael Pilarz • Gain the confi dence and knowledge to skillfully represent either an Buffalo, NY insurer or insured, whether it be during the policy drafting stage or a Christopher W. Healy, Esq. claim dispute Reed Smith LLP New York, NY Insurance Law Practice, Second Edition covers almost every insurance- related topic, discussing general principles of insurance contracts, PRODUCT INFO AND PRICES litigation involving insurance contracts, types of insurance policies, 41256 | Book (w/ 2014 supplement) | and other pertinent issues. New and experienced practitioners alike 1,588 pages | loose-leaf, two-volume will benefi t from the practical and comprehensive approach to this complex area of the law. -

Insurance Law Page 1 of 2

Insurance Law Page 1 of 2 Insurance Law involves the regulation of all types of insurance of risk: property, automobile, personal and professional liability, life, health, long-term care, and disability, among others. Most areas of the insurance industry are regulated, so insurance law attorneys should be comfortable with administrative law. Each type of insurance is also covered by regulations specific to its subject area. Health, long-term care, and disability insurance involve health care law. Insurance law attorneys should be experts in contract law and have experience with contract drafting. Corporate law knowledge and transactional skills are useful for insurance law attorneys. A background in alternative dispute resolution (ADR), such as negotiation, mediation, and arbitration, is important. Insurance contracts often use ADR clauses as a way to reduce transaction costs and increase efficiency. And since some types of insurance, such as life, health, and disability insurance, are offered as benefits through employers, employee benefits law is also relevant. For more information about insurance law, see the Legal Information Institute’s Wex encyclopedia “Insurance” page, the American Bar Association’s Tort Trial and Insurance Practice Section, and the International Risk Management Institute. Job Type Typical Duties Federal Agencies Draft and enforce rules and regulations. National Flood Insurance Draft and enforce external and internal policies and procedures. Program (NFIP) Liaise with state regulators and insurance companies. Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC) Federal Jobs State Agencies Provide advice and counsel to state insurance regulators regarding Florida Office of Insurance regulatory issues. Regulation Review applications from insurance companies. State Jobs Work on the issuance of rules, orders, and other legal documents. -

Taxation of Insurance Companies

Taxation of Insurance Companies Informational Paper 10 Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau January, 2017 Taxation of Insurance Companies Prepared by Sean Moran Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau One East Main, Suite 301 Madison, WI 53703 http://legis.wisconsin.gov/lfb Taxation of Insurance Companies This paper provides background information example, under a pure "term" life insurance on the taxation of insurance companies in policy, the insured pays a premium which Wisconsin. While the main topic is the separate obligates the insurance company to pay a specific state premiums tax imposed on certain insurance sum in the event of the insured's death during the companies, the imposition of the state corporate term of the policy. Term insurance is the most income/franchise tax is also discussed. straightforward type of life insurance policy in that the premium provides coverage only in the In order to put the taxation of insurance com- event of death during the policy's specified term. panies in focus, information is provided on the characteristics of the insurance industry and the Certain life insurance policies perform a bank- Wisconsin operations of some of the major com- like function in that policyholder premiums are panies in different lines of insurance. The regula- invested by the insurer on behalf of the insured. tory role of the Office of the Commissioner of Income from such investments is credited to the Insurance (OCI) is also discussed briefly. Finally, policyholder's account in determining the policy's a discussion of the rationale and issues of insur- "cash surrender value," which is the amount which ance taxation is presented and the insurance tax the insured would receive if he or she cancels the provisions of other states are outlined. -

The Cooperative Health Insurance Law Issued by the Royal Decree No

The Cooperative Health Insurance Law Issued by the Royal Decree No. 10 dated 1/5/1420H(1) Based on the Cabinet of Ministers Resolution No 71 dated 27/4/1420H Published in Umm Qura Gazette, issue No 3762 dated 30 /5/ 1420H Article (1) This law aims at providing and arranging health care for non- Saudis residing in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia as it may also apply to Saudi citizens as well as others, upon a resolution from the Cabinet of Ministers. Article (2) Cooperative health insurance shall cover all those it applies on and their families in accordance with paragraph ’B” of Article (5). Article (3) Taking into consideration the implementation phases mentioned in paragraph “B” of Article (5) and the requirements of articles (12&13) of this law, whoever sponsors a foreign resident shall be committed to subscribe for him, to the cooperative health insurance. The residence permit [Iqamah] may not be granted or renewed save after obtaining the cooperative health insurance policy that covers residence period. Article (4) A council for health insurance shall be established headed by the Minister of Health and membership of: a- A representative of each of the following Ministries, not less in rank than undersecretary, nominated by their respective commands: Interior, Labor and Social Affairs, Finance and National Economy and the Ministry of Commerce. b- A representative of the Saudi Chambers of Commerce and Industry Council, nominated by the Minister of Commerce, and a representative of the cooperative health insurance companies, to be nominated by the Minister of Finance and National Economy in consultation with the Minister of Commerce. -

Insurance & Reinsurance Law Report

2016 INSURANCE & REINSURANCE LAW REPORT 2016 INSURANCE & REINSURANCE LAW REPORT An Honor Most Sensitive: Duties of Mutual Company Directors in the Context of Significant Strategic Transactions By Daniel J. Neppl and Sean M. Carney ����������������������������������������������������������������������������1 Is the Supreme Court “Pro-Arbitration”? The Answer is More Complicated Than You Think By Susan A. Stone and Daniel R. Thies ���������������������������������������������������������������������������� 10 Remedies for the Rogue Arbitrator By William M. Sneed ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 16 Unringing the Bellefonte?— New Developments Regarding the Cost-Inclusiveness of Facultative Certificate Limits By Alan J. Sorkowitz �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������22 Biographies .........................................................................................................................28 The Insurance & Reinsurance Law Report is published by the global Insurance and Financial Services group of Sidley Austin LLP� This newsletter reports recent developments of interest to the insurance and reinsurance industry and should not be considered as legal advice or legal opinion on specific facts� Any views or opinions expressed in the newsletter do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Sidley Austin LLP or its clients� Sidley Austin LLP is one of the world’s premier law firms with -

Coverage Information in Insurance Law

Scholarship Repository University of Minnesota Law School Articles Faculty Scholarship 2017 Coverage Information in Insurance Law Daniel Schwarcz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/faculty_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Daniel Schwarcz, Coverage Information in Insurance Law, 101 MINN. L. REV. 1457 (2017), available at https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/faculty_articles/594. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in the Faculty Scholarship collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Article Coverage Information in Insurance Law Daniel Schwarcz† Introduction ........................................................................... 1458 I. Three Types of Coverage Information: Purchaser information, Policy information, and Judicial Information .................................................................. 1466 A. Insurance Law and Purchaser Information ........ 1467 B. Insurance Law and Policy Information ............... 1471 C. Insurance Law and Judicial Information ............ 1476 II. Rationales for Laws and Regulations that Promote the Three Types of Coverage Information .................. 1480 A. Rationales for Promoting Purchaser Information in Insurance Markets ........................................... 1481 1. Promoting More Efficient Insurance Policies .. 1481 2. Promoting Matching Between Policyholders -

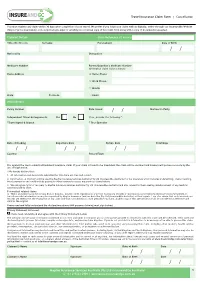

Cancellation Claim Form

Travel Insurance Claim Form | Cancellation You must register any claim within 30 days after completion of your travel. We prefer if you lodge your claim with us digitally, either through our InsureandGo Website (https://quote.insureandgo.com.au/policylogin.aspx) or emailing us a scanned copy of this claim form along with a copy of documents requested. Claimant Details Claim Reference (if known) Title (Mr/Mrs etc) Surname Forename(s) Date of Birth / / Nationality Occupation Medicare Number Parent/Guardian’s Medicare Number (If medical claim is for a minor) Home Address ' Home Phone ' Work Phone ' Mobile State Postcode Email Policy Details Policy Number Date Issued / / Number in Party Independent Travel Arrangements: Yes No If no, provide the following *: *Travel Agent & Branch * Tour Operator Date of Booking Departure Date Return Date Total Days / / / / / / Country Resort/Town It is against the law to submit a fraudulent insurance claim. If your claim is found to be fraudulent the claim will be declined and Insurers will pursue recovery by the use of legal action. I/We hereby declare that: 1. All information and documents submitted for this claim are true and correct. 2. Information on this form will be used by Mapfre Insurance Services Australia Pty Ltd (InsureandGo Australia) for my insurance which includes underwriting, claims handling, fraud prevention and could include passing to other insurers to access my previous claims history. 3. We subrogate rights of recovery to Mapfre Insurance Services Australia Pty Ltd (InsureandGo Australia) and also consent to them seeking reimbursement of any medical expenses paid by them. For medical related claims: 4. -

A Brief History of Reinsurance by David M

Article from: Reinsurance News February 2009 – Issue 65 A BRIEF HISTORY OF REINSURANCE by David M. Holland, FSA, MAAA goods over a number of ships in order to reduce the risk from any one boat sinking.2 • In 1601, during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, the English Parliament enacted “AN ACTE CONCERNINGE MATTERS OF ASSURANCES, AMONGSTE MARCHANTES,” which states: “… by meanes of whiche Policies of Assurance it comethe to passe, upon the losse or perishinge of any Shippe there followethe not the undoinge of any Man, but the losse lightethe rather easilie upon many, then heavilie upon fewe. …”3 • Edwin Kopf, FCAS, in his 1929 paper “Notes on Origin and Development of Reinsurance”4 translates from a German text by Ehrenberg as follows: einsurance is basically insurance for insur- ance companies. Park, writing in 1799, “Reinsurance achieves to the utmost more colorfully stated: extent the technical ideal of every branch R of insurance, which is actually to effect (1) “RE-ASSURANCE, as understood by the law of the atomization, (2) the distribution and England, may be said to be a contract, which the (3) the homogeneity of risk. Reinsurance first insurer enters into, in order to relieve himself is becoming more and more the essential from those risks which he has incautiously under- element of each of the related insurance taken, by throwing them upon other underwriters, branches. It spreads risks so widely and who are called re-assurers.”1 effectively that even the largest risk can be accommodated without unduly burden- 5 In order for commerce to flourish, there has to be a ing any individual.” way to deal with large financial risks.