Research Poster Sample

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAPTER V, , ************ * * Approach to the Liri Valley

CHAPTER V, , ************ * * Approach to the Liri Valley A. PLANS FOR THE THIRD PHASE See Map No. 8 VJENERAL Clark anticipated on 16 December the early conclusion of Phase II and issued Operations Instruction No. 12. {See Annex No. 2F.) At that time San Pietro was still under attack, but there were indications that the enemy was preparing to withdraw to new positions. San Vittore might be held in some strength, but by clearing the slopes of Sammucro II Corps would cause that village to be untenable. The next barriers to the I4ri Valle}^ were Cedro Hill and Mount Porchia south of Highway 6; Cicerelli Hill, Mount I^a Chiaia, and the hills to the northeast on the north side of the highway; and the mountains centering around Mount Majo (Hill 1259). Once through the Porchia-I^a Chiaia defenses, the chief obstacle south of the highway was Mount Trocchio; north of the highway was the town of Cervaro, ringed by low hills and dominated on the north by mountains. II Corps was again to make the main effort in the center along the axis of Highway 6. The first objectives were Mounts Porchia and Trocchio. It was to be prepared to assist VI Corps in the capture of the high ground north west of Cassino, and was to secure a bridgehead over the Rapido River. After the bridgehead was secured, II Corps was to use the maximum amount of armor to drive northwest through the Iviri Valley to the Melfa River. The 1st Armored Division was attached to II Corps for that purpose. -

“Wars Should Be Fought in Better Country Than This” the First Special Service Force in the Italian Mountains by Kenneth Finlayson

“Wars should be fought in better country than this” The First Special Service Force in the Italian Mountains by Kenneth Finlayson 48 Veritas eavy fighting raged across the summit of Monte La Canadian-American infantry unit of World War II. Defensa. The First Special Service Force (FSSF) was Activated on 20 July 1942 at Fort William Henry Harrison, decisively engaged with the German defenders on near Helena, Montana, the FSSF was originally intended H 2 the mountain. LTC Ralph W. Becket, commanding 1st for a special mission in Norway. Operation PLOUGH Battalion of the First Regiment, witnessed the assault was designed to destroy the Norwegian hydroelectric of a Second Regiment platoon against a German dam at Vermork that was producing deuterium, the machine gun position. 1LT Maurice Le Bon led his men “heavy water” vital to the German nuclear program.3 The to a concealed position 30 yards from the flank of the cancellation of PLOUGH resulted in the FSSF being sent enemy. “I watched all this develop, not missing a thing. first to the Aleutians and then to the Mediterranean. When our machine guns and mortars opened fire from It was in southern Italy that the Force first saw combat. the right, the enemy replied with strong machine gun The Force’s reputation as an elite unit was made during and Schmeisser pistol fire,” said Becket. “Suddenly our the U.S. Fifth Army’s grueling campaign to break through fire stopped and for the first and only time I heard the the German Winter Line south of Rome. This article will order – in Le Bon’s strong French-Canadian accent– ‘Fix look at the two phases of this operation and show how bayonets!’ A moment later Le Bon emerged into the the bloody fighting in the mountains of Italy had a deep clearing with his section and the men, with bayonets and lasting impact on the unit. -

The Gothic Line

Green is Bologna Discover the Gothic Line © Martino Viviani © Martino Viviani Walking along the paths of the Gothic Line means retracing the history and the events that involved the men and women who fought in what was the last German defensive outpost during the Italian Campaign. Between October 1944 and April 1945, the Bologna Apennines were the setting of large battles between the German army and the allied forces advancing from the south of the Italian peninsula. The historic itinerary unwinds from west to east: it starts at Lake Scaffaiolo in the Corno alle Scale Regional Park and arrives in Tossignano in the Park of the Vena del Gesso Romagnolo. Milan Venice Bologna Florence Rome How to find us Bologna is easy to reach using the main means of transport. Bologna Bologna G. Marconi Airport Bologna Central Station Motorways (A1-A14) Gothic Line Trekking Lake Scaffaiolo 1st Stage: Length: 15.8 km Difference in level:+600 -1,800 Duration: 6 h Rocca Corneta 2nd Stage: Length: 14 km Difference in level:+600 -1150 Duration: 5 h Abetaia 3rd Stage: Iola Length: 15,1 km Difference in level:+500 -490 Duration: 5 h Castel d’Aiano 4th Stage: MdSpè Length: 20 km Difference in level:+750 -1,300 Duration: 7 h Vergato 5th Stage: Monte Salvaro Length: 15,6 km Difference in level:+850 -660 Duration: 6 h Monte Sole 6th Stage: Vado Length: 21 km Difference in level:+1050 -1000 Duration: 7 h Brento Livergnano 7th Stage: Monte delle Formiche Length: 16,5 km Difference in level:+1100 -1200 Duration: 6 h Monterenzio 8th Stage: Monte Cerere Length: 21 km Difference in level:+700 -800 Duration: 7 h S. -

The London Gazette of TUESDAY, 6Th JUNE, 1950

jRtttnb, 38937 2879 SUPPLEMENT TO The London Gazette OF TUESDAY, 6th JUNE, 1950 Registered as a newspaper MONDAY, 12 JUNE, 1950 The War Office, June, 1950. THE ALLIED ARMIES IN ITALY FROM SRD SEPTEMBER, 1943, TO DECEMBER; 1944. PREFACE BY THE WAR OFFICE. PART I. This Despatch was written by Field-Marshal PRELIMINARY PLANNING AND THE Lord Alexander in his capacity as former ASSAULT. Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Armies in Italy. It therefore concentrates primarily upon Strategic Basis of the Campaign. the development of the land campaign and the The invasion of Italy followed closely in time conduct of the land battles. The wider aspects on the conquest of Sicily and may be therefore of the Italian Campaign are dealt with in treated, both historically and strategically, as reports by the Supreme Allied Commander a sequel to it; but when regarded from the (Field-Marshal Lord Wilson) which have point of view of the Grand Strategy of the already been published. It was during this- war there is a great cleavage between the two period that the very close integration of the operations. The conquest of Sicily marks the Naval, Military and Air Forces of the Allied closing stage of that period of strategy which Nations, which had been built up during the began with the invasion of North Africa in North African Campaigns, was firmly con- November, 1942, or which might, on a longer solidated, so that the Italian Campaign was view, be considered as beginning when the first British armoured cars crossed the frontier wire essentially a combined operation. -

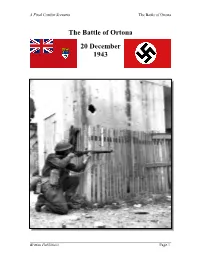

The Battle of Ortona

A Final Combat Scenario The Battle of Ortona The Battle of Ortona 20 December 1943 Britton Publishers Page 1 A Final Combat Scenario The Battle of Ortona History The Battle of Ortona (December 20, 1943 to December 28, 1943) was a small yet extremely fierce battle fought between German Fallschirmjäger, and assaulting Canadian forces from the 1st Canadian Infantry Division. It was the culmination of the fighting on the Adriatic front in Italy during "Bloody December" and was considered among Canada's greatest achievements during the war. Taking place in the small Adriatic Sea town of Ortona, with its peacetime population of 10,000, the battle was the site of what was perhaps the deadliest close quarter combat engagement of the entire war. Some dubbed this "Little Stalingrad." Background The Eighth Army's offensive on the Winter Line defenses east of the Apennine Mountains had commenced on November 23 with the crossing of the river Sangro. By the end of the month the main Gustav Line defenses had been penetrated and the Allied troops were fighting their way forward to the next river, the Moro, four miles north of the mouth of which lay Ortona. For the Moro crossing in early December the exhausted British 78th Infantry Division on the Allied right flank on the Adriatic coast had been relieved by Canadian 1st Infantry Division. By mid December, after fierce fighting in the cold, wet and mud the Division's 1st Infantry Brigade had fought its way to within two miles of Ortona and was relieved by 2nd Infantry Brigade for the advance on the town. -

Italian Campaign- Final.Pdf

The Italian Campaign The Italian Campaign began with the invasion of Sicily in July 1943. The invasion went by the code name Operation Husky. It was the first attack on Axis-held Europe. It was also the first large scale use of paratroops in the war. Sicily was captured in a 38-day campaign that cost the U.S. 7th Army 7,500 and British troops 11,500 casualties The Germans lost 12,000 men killed or captured. The Italians lost 145,000 men killed or captured. “ The astonishing Americans, they fight all day, attack all night and shoot all the time” -From a letter written by a German soldier killed in the Sicily invasion. Time Life WWII: The Italian Campaign Mainland Italy was attacked by Allied Troops on September 8, 1943, just as the Italian government was surrendering to the Allied forces. The allies were now fighting only the Germans for control of Italy. Allied troops first took Salerno, then drove onto Naples. The original mission had been to drive Italy out of the war, once that had been achieved, their mission became to engage German troops so that they would not be able to reenforce Normandy, to do so they needed to push on to Rome. The first step in taking Rome was to face the German forces at the Winter Line, which was followed by the landing of troops at Anzio. At the Winter Line, the Allies had severe problems breaking into the Lirie Valley. After months of fighting and sustaining heavy losses, the Allies were able to break into the Lirie Valley, forcing the Germans to retreat. -

Battle of Monte Cassino

Battle of Monte Cassino 17 January thru 18 May 1944 Monte Cassino Abbey in November 2004 The Battle of Monte Cassino (also known as the Battle for Rome and the Battle for Cassino) was a costly series of four assaults by the Allies against the Winter Line in Italy held by the Germans and Italians during the Italian Campaign of World War II. The intention was a breakthrough to Rome. At the beginning of 1944, the western half of the Winter Line was being anchored by Germans holding the Rapido, Liri, and Garigliano valleys and some of the surrounding peaks and ridges. Together, these features formed the Gustav Line. Monte Cassino, a historic hilltop abbey founded in AD 529 by Benedict of Nursia, dominated the nearby town of Cassino and the entrances to the Liri and Rapido valleys, but had been left unoccupied by the German defenders. The Germans had, however, manned some positions set into the steep slopes below the abbey's walls. 1 Fearing that the abbey did form part of the Germans' defensive line, primarily as a lookout post, the Allies sanctioned its bombing on 15 February and American bombers proceeded to drop 1,400 tons of bombs onto it. The destruction and rubble left by the bombing raid now provided better protection from aerial and artillery attacks, so, two days later, German paratroopers took up positions in the abbey's ruins. Between 17 January and 18 May, Monte Cassino and the assaulted four times by Allied troops, the last involving twenty divisions attacking along a twenty-mile Gustav defenses were front. -

Guida Al Viaggio a Tappe Nei Luoghi Della II Guerra Mondiale in Abruzzo

Guida al viaggio a tappe nei luoghi della II Guerra Mondiale in Abruzzo Sulla Linea Gustav. Il cammino della memoria. Pubblicato con il contributo di PAR FAS ABRUZZO 2007-2013 - Obiettivo 1.3 - Linea di Azione 1.3.1.b “Avviso pubblico per la selezione e il finanziamento a fondo perduto di nuove iniziative di imprenditoria legate all’incentivazione e sviluppo di servizi turistici’ OBIETTIVOTURISMO www.abruzzoturismo.it con il cofinanziamento dellaSoc. Coop Terracoste a r.l. Realizzato da Istituto Abruzzese per le Aree Protette (IAAP) TESTI Paola Natale, Antonella Rossetti GRAFICA E IMPAGINAZIONE Antonella Rossetti TRADUZIONI Chiara Schettini FOTO Rebecca Bucci, Imperial War Museum London, Fondazione Brigata Maiella, WinterLine Asd, Alessandro Teti, Erika Iacobucci, Archivio Comunale di Alfedena. Prima edizione: giugno 2017 Logo sfondo azzurro Logo sfondo bianco DESCRIZIONE La realizzazione di questo logo è frutto della collaborazione di tutto il gruppo di lavoro del progetto “Sulla Linea Gustav - Il cammino della memoria”. Il logo rappresenta il fiore, sbocciato, della ginestra, di colore giallo (#ffed00). Questo fiore è stato scelto per due motivi: il primo perchè è un fiore molto comune lungo diverse zone della Linea Gustav; il secondo perchè riesce a crescere e resistere in zone e climi ostili alla crescita florea- le, quindi simbolo di resistenza. Il gambo del fiore rappresenta un filo spi- nato bianco, che gira intorno alla ginestra, con all’estremità una freccia: vuole rappresentare il cammino, lungo una zona che, un tempo, era di guerra. Inoltre, nel complesso, c’è un chiaro riferimento al simbolo infor- matico @, scelto perchè il progetto cercherà di promuovere il territorio anche utilizzando le ultime tecnologie di comunicazione informatiche. -

DON't CALL 'EM DODGERS! Lady Nancy Astor and The

DON’T CALL ‘EM DODGERS! Lady Nancy Astor and the misnomer of the decade THE ITALIAN CAMPAIGN What Canadians experienced in the Mediterranean BRINGING THEM HOME Symbolizing over 60,000 souls, the Eternal Flame comes to TMM May – August, 2019 The PPCLI Museum & Archives Newsletter Vol. 2, No. 2 The Gault Press is produced by The PPCLI Museum & Archives, located at The Military Museums in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. If you are looking to find out more about PPCLI and its history, please don't hesitate to contact us directly at [email protected]. Museum General Manager: Sergeant Nate Blackmore Collections Manager: Corporal Andrew Mullett Artefact Specialist: James Morgan Archivist: Jim Bowman The Gault Press Editor: Cover: PPCLI in Rome on the first J. Neven-Pugh anniversary of D-Day, 6 June 1945: Sgt. M. [email protected] Hanna, Sgt. Ben Kelter, RSM W.M. Lambert, CSME Rainbird. PPCLI Archives: P70(71)-4 2 May – August, 2019 The PPCLI Museum & Archives Newsletter Vol. 2, No. 2 Theme: Anything But Dodgers: PPCLI & the Italian DON’T CALL ’EM THE ITALIAN CAMPAIGN BRINGING THEM HOME Campaign, DODGERS! LADY NANCY ASTOR WHAT CANADIANS SYMBOLIZING OVER 60,000 SWW AND THE MISNOMER OF EXPERIENCED ONCE THEY SOULS, THE ETERNAL FLAME, THE DECADE ARRIVED IN ITALY COMES TO TMM Excerpt from “Situation in Italy Winter 1943 – 1944.” PPCLI Archives: 74-4-15 Anything But Dodgers On 6 June 1944, at the height of the Second World War, Allied forces launched a massive assault against the occupied coast of Normandy in what would become known as “D-Day”. -

Italian Front in World War II

Italian Front in World War II Dwight D. Eisenhower Library Collection of 20th Century Military Records Series III Box 3- History of the 15th Army Box 12- History of AFHQ Box 15- From the Volturno to the Winter Line Box 16- 5th Army History Series II Box 23- Headquarters 5th Army, Office of the Surgeon, The Medical Story of Anzio Series I Box 33= #115- Air Phase of the Italian Campaign Papers of Dwight Eisenhower, Pre-Presidential, 1916-52 Box 1- Alexander, Harold R.L. (1) History of Italian Campaign (6) (7) Box 22- Churchill, Winston (6) (7)- Italian Campaign Box 22- Clark, Mark W. Rapido River incident Papers of C.D. Jackson Box 1- Algiers—London (1)-(9)- conditions in liberated Italy; PWB Leaflet operations Box 21- Avalanche-Baytown Box 22- Food Situation in Italy, 1943 Box 24- Italian Situation (1) – (3) Box 25- PWB Results- Italian situation Allied bombing; Allied invasion Of Italy Papers of Edward Lilly Box 29- OWI- London – Carroll, Wallace 1944 91)(2) – Anzio and Anglo- American Operations Boxes 38-39- PWB/AFHQ- several folders including psychological warfare plan For BAYTOWN and AVALANCHE assaults against Italian mainland Box 39- PWB/AFHQ- Propaganda Reaction Sept 1943-May1945- Italian Campaigns Box 40= Psychological Warfare in the Mediterranean Theater Papers of Lauris Norstad Boxes 1-5, 8-15 (Pertains to air operations in Italy and the Mediterranean 1943- 1944 Papers of Charles Ryder Box 4- folders on 34th Infantry Division including Hq. 34th Inf. Div. G-3 Historical Narrative and Journal Sept 14, 1943- April 30, 1945 – Italian Campaign Box 9- Unit Histories and Campaign Reports- From the Volturno to the Winter Line; The Winter Line; Road to Rome; The Advance on Rome; Finito! The Po Valley Campaign US Army Unit Records 1st Armored Division- Boxes 18-29 3rd Infantry Division- 762-782, esp. -

The Cassino - Anzio Operation

CHAPTER XI •***______ The Cassino - Anzio Operation A. GAINS OF THE CASSINO-ANZIO CAMPAIGN 1 HE Cassino-Anzio campaign, 16 January-31 March, failed in its major objec tive, the linking of the beachhead with the southern front. Initial success by the British 10 Corps in its attack across the Garigliano created a serious threat to the Gustav Iyine by 19 January; however, the enemy moved reserves swiftly and stopped our advance by strong counterattacks at critical points. By dis rupting the attempt of the 46 Division to cross the upper Garigliano on 19-20 January the Germans continued to hold the south flank of the Iyiri Valley. They were therefore well prepared to meet the assault of the 36th Division across the Rapido River on 20-22 January. Fifth Army gained complete tactical surprise in its landing at Anzio on 22 January. Before the enemy could rush reinforcements to the Colli L,aziali area VI Corps had penetrated an average distance of ten miles from Anzio and threatened the German lines of communication south of Rome. Kesselring met this new danger by bringing in troops from northern Italy, and on 3 Feb ruary the German Fourteenth Army began a series of counterattacks which recovered important ground. Thereafter VI Corps was forced to assume the defensive, and March ended with the opposing forces at the beachhead locked in stalemate. On the southern front Fifth Army continued its efforts to smash through the Gustav I4ne, held by the German Tenth Army. Failing in its first attempt to cross the Rapido north of Cassino, the 34th Division forced a break in the German defenses by 31 January. -

The Legacy of Military Necessity in Italy: War and Memory in Cassino and Monte Sole

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 4-23-2013 12:00 AM The Legacy of Military Necessity in Italy: War and Memory in Cassino and Monte Sole Cynthia D. Brown The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Jonathan Vance The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in History A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Cynthia D. Brown 2013 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Brown, Cynthia D., "The Legacy of Military Necessity in Italy: War and Memory in Cassino and Monte Sole" (2013). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 1255. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/1255 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Legacy of Military Necessity in Italy: War and Memory in Cassino and Monte Sole (Thesis format: Monograph) by Cynthia D. Brown Graduate Program in History A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Cynthia D. Brown 2013 Abstract The rise of Benito Mussolini’s Fascist party and its disastrous alliance with Nazi Germany remains one of the most well-known parts of Italy’s Second World War experience, at least in English historical literature.