Chapter 6. Magnetostatic Fields in Matter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basic Magnetic Measurement Methods

Basic magnetic measurement methods Magnetic measurements in nanoelectronics 1. Vibrating sample magnetometry and related methods 2. Magnetooptical methods 3. Other methods Introduction Magnetization is a quantity of interest in many measurements involving spintronic materials ● Biot-Savart law (1820) (Jean-Baptiste Biot (1774-1862), Félix Savart (1791-1841)) Magnetic field (the proper name is magnetic flux density [1]*) of a current carrying piece of conductor is given by: μ 0 I dl̂ ×⃗r − − ⃗ 7 1 - vacuum permeability d B= μ 0=4 π10 Hm 4 π ∣⃗r∣3 ● The unit of the magnetic flux density, Tesla (1 T=1 Wb/m2), as a derive unit of Si must be based on some measurement (force, magnetic resonance) *the alternative name is magnetic induction Introduction Magnetization is a quantity of interest in many measurements involving spintronic materials ● Biot-Savart law (1820) (Jean-Baptiste Biot (1774-1862), Félix Savart (1791-1841)) Magnetic field (the proper name is magnetic flux density [1]*) of a current carrying piece of conductor is given by: μ 0 I dl̂ ×⃗r − − ⃗ 7 1 - vacuum permeability d B= μ 0=4 π10 Hm 4 π ∣⃗r∣3 ● The Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (German national metrology institute) maintains a unit Tesla in form of coils with coil constant k (ratio of the magnetic flux density to the coil current) determined based on NMR measurements graphics from: http://www.ptb.de/cms/fileadmin/internet/fachabteilungen/abteilung_2/2.5_halbleiterphysik_und_magnetismus/2.51/realization.pdf *the alternative name is magnetic induction Introduction It -

Electrostatics Vs Magnetostatics Electrostatics Magnetostatics

Electrostatics vs Magnetostatics Electrostatics Magnetostatics Stationary charges ⇒ Constant Electric Field Steady currents ⇒ Constant Magnetic Field Coulomb’s Law Biot-Savart’s Law 1 ̂ ̂ 4 4 (Inverse Square Law) (Inverse Square Law) Electric field is the negative gradient of the Magnetic field is the curl of magnetic vector electric scalar potential. potential. 1 ′ ′ ′ ′ 4 |′| 4 |′| Electric Scalar Potential Magnetic Vector Potential Three Poisson’s equations for solving Poisson’s equation for solving electric scalar magnetic vector potential potential. Discrete 2 Physical Dipole ′′′ Continuous Magnetic Dipole Moment Electric Dipole Moment 1 1 1 3 ∙̂̂ 3 ∙̂̂ 4 4 Electric field cause by an electric dipole Magnetic field cause by a magnetic dipole Torque on an electric dipole Torque on a magnetic dipole ∙ ∙ Electric force on an electric dipole Magnetic force on a magnetic dipole ∙ ∙ Electric Potential Energy Magnetic Potential Energy of an electric dipole of a magnetic dipole Electric Dipole Moment per unit volume Magnetic Dipole Moment per unit volume (Polarisation) (Magnetisation) ∙ Volume Bound Charge Density Volume Bound Current Density ∙ Surface Bound Charge Density Surface Bound Current Density Volume Charge Density Volume Current Density Net , Free , Bound Net , Free , Bound Volume Charge Volume Current Net , Free , Bound Net ,Free , Bound 1 = Electric field = Magnetic field = Electric Displacement = Auxiliary -

Module 3 : MAGNETIC FIELD Lecture 20 : Magnetism in Matter

Module 3 : MAGNETIC FIELD Lecture 20 : Magnetism in Matter Objectives In this lecture you will learn the following Study magnetic properties of matter. Express Ampere's law in the presence of magnetic matter. Define magnetization and H-vector. Understand displacement current. Assemble all the Maxwell's equations together. Study properties and propagation of electromagnetic waves in vacuum. Magnetism in Matter In our discussion on electrostatics, we have seen that in the presence of an electric field, a dielectric gets polarized, leading to bound charges. The polarization vector is, in general, in the direction of the applied electric field. A similar phenomenon occurs when a material medium is subjected to an external magnetic field. However, unlike the behaviour of dielectrics in electric field, different types of material behave in different ways when an external magnetic field is applied. We have seen that the source of magnetic field is electric current. The circulating electrons in an atom, being tiny current loops, constitute a magnetic dipole with a magnetic moment whose direction depends on the direction in which the electron is moving. An atom as a whole, may or may not have a net magnetic moment depending on the way the moments due to different elecronic orbits add up. (The situation gets further complicated because of electron spin, which is a purely quantum concept, that provides an intrinsic magnetic moment to an electron.) In the absence of a magnetic field, the atomic moments in a material are randomly oriented and consequently the net magnetic moment of the material is zero. However, in the presence of a magnetic field, the substance may acquire a net magnetic moment either in the direction of the applied field or in a direction opposite to it. -

Magnetism in Transition Metal Complexes

Magnetism for Chemists I. Introduction to Magnetism II. Survey of Magnetic Behavior III. Van Vleck’s Equation III. Applications A. Complexed ions and SOC B. Inter-Atomic Magnetic “Exchange” Interactions © 2012, K.S. Suslick Magnetism Intro 1. Magnetic properties depend on # of unpaired e- and how they interact with one another. 2. Magnetic susceptibility measures ease of alignment of electron spins in an external magnetic field . 3. Magnetic response of e- to an external magnetic field ~ 1000 times that of even the most magnetic nuclei. 4. Best definition of a magnet: a solid in which more electrons point in one direction than in any other direction © 2012, K.S. Suslick 1 Uses of Magnetic Susceptibility 1. Determine # of unpaired e- 2. Magnitude of Spin-Orbit Coupling. 3. Thermal populations of low lying excited states (e.g., spin-crossover complexes). 4. Intra- and Inter- Molecular magnetic exchange interactions. © 2012, K.S. Suslick Response to a Magnetic Field • For a given Hexternal, the magnetic field in the material is B B = Magnetic Induction (tesla) inside the material current I • Magnetic susceptibility, (dimensionless) B > 0 measures the vacuum = 0 material response < 0 relative to a vacuum. H © 2012, K.S. Suslick 2 Magnetic field definitions B – magnetic induction Two quantities H – magnetic intensity describing a magnetic field (Système Internationale, SI) In vacuum: B = µ0H -7 -2 µ0 = 4π · 10 N A - the permeability of free space (the permeability constant) B = H (cgs: centimeter, gram, second) © 2012, K.S. Suslick Magnetism: Definitions The magnetic field inside a substance differs from the free- space value of the applied field: → → → H = H0 + ∆H inside sample applied field shielding/deshielding due to induced internal field Usually, this equation is rewritten as (physicists use B for H): → → → B = H0 + 4 π M magnetic induction magnetization (mag. -

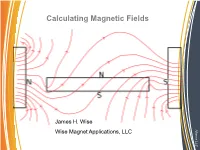

Calculating Magnetic Fields, Please Call

Calculating Magnetic Fields James H. Wise Alliance LLC Alliance Wise Magnet Applications, LLC Magnetic Fields: What and Where? Magnetic fields: Sources: • Appear around electric currents • Surround magnetic materials Properties: • They have a direction • They possess magnitude • They are vector fields Alliance LLC Alliance Reference for Definition Field descriptions and behavior See Chapters 1, 2 and 3 of “The Feynman Lectures in Physics”, Vol.II by Feynman, Leighton and Sands, Addison Wesley,1964, ISBN 0 -201-2117-X-P . Chapter 1 is my favorite starting point for thinking about fields. The next slide is derived from that. Alliance LLC Alliance Examples of Fields Fields: • When a quantity varies with location in space, (x,y,z,t), it is said to be a field. • Temperature around a heat source forms a field. • As the temperature is only a single quantity associated with it is said to be a scalar field • Heat flow has a direction and thus 3 quantities that change with (x,y,z) and perhaps a time dependence • Because it has 3 spatial components obeying the rules of vectors, it is said to be a vector field. Alliance LLC Alliance Magnetic Fields of Permanent Magnets • The magnetic field was originally treated as originating from charges. • Pole strength was interpreted as the amount of magnetic charge on the surface of a magnet If the charge distribution was known, the force outside the magnet could be computed correctly • The charge model does not give the correct results for fields inside magnets. • The pole model is useful for gaining an intuitive view for qualitative results. -

Electromagnetism 3. Magnetization (Lectures 7–9)

Electromagnetism Handout 3: 3. Magnetization (Lectures 7{9): Here is the proof of a useful vector identity. First recall Stokes' theorem which states that Z I r × A · dS = A · dl: (1) Let us suppose that A takes the form A(r) = f(r)c where c 6= c(r) is a constant vector. Hence we have r × A = fr × c − c × rf = −c × rf (2) since r × c = 0 (because c is a constant vector, its derivative vanishes). Stokes' theorem then gives us I I Z Z A · dl = c · f dl = − c × rf · dS = −c · rf × dS; (3) but this is true for any c and so I Z f dl = − rf × dS: (4) Now let us choose f = r^ · r0 and take the gradient and integral around a closed loop in the primed coordinates: I Z Z (r^ · r0) dl0 = − r0(r^ · r0) × dS0 = −r^ × dS0 (5) which works because r0(r^ · r0) = r^. In summary: I Z r^ · r0 dl0 = dS0 × r^: (6) We will use this to show that the magnetic vector potential from a magnetic dipole is given by µ A = 0 m × r^; (7) 4πr2 where m is the magnetic dipole moment. For example, if we put m parallel to z and use spherical polars, we have that µ A = 0 m sin θ φ^; (8) 4πr2 and so 1 @ 1 @ B = r × A(r) = (r sin θ A )r^ − (r sin θ A )θ^; (9) r2 sin θ @θ φ r sin θ @r φ because Ar = Aθ = 0 and hence µ m 2 cos θ sin θ B = 0 r^ + θ^ ; (10) 4π r3 r3 which is the same form as an electric dipole. -

Jackson 5.22 Homework Problem Solution Dr

Jackson 5.22 Homework Problem Solution Dr. Christopher S. Baird University of Massachusetts Lowell PROBLEM: Show that in general a long, straight bar of uniform cross-sectional area A with uniform lengthwise magnetization M, when placed with its flat end against an infinitely permeable flat surface, adheres with a force given approximately by μ F ≈ 0 A M 2 2 Relate your discussion to the electrostatic considerations in Section 1.11. SOLUTION: First note that the problem does not say the bar is a circular cylinder. We can't just use the fields due to a circular cylinder to solve this problem. The bar has arbitrary cross-sectional shape. Assume the magnetization is away from the plate, in the positive z direction, M=M ẑ , and the plate lies in the x-y plane. An infinitely permeable flat surface acts just like a perfect mirror, so we can just represent its effects by a second image bar with the exact same shape and magnetization placed just below the first. The magnetization of each bar can be represented as due to an effective magnetic charge distribution. Because the magnetization is uniform, the magnetic charges must be on the surface and not inside. Furthermore, the sides of the bar are parallel to the magnetization, so it has no charge. Also, the bars are long, so we can assume the top face of the real bar and the bottom face of the image bar are so far away as to have no effect. On the bottom face of the real bar there is a magnetization surface charge density: σ = ⋅ M n M σ =(−̂ )⋅( ̂) M z M z σ =− M M which exists at z = 0 within the circumference of the real bar. -

Electromagnetic Fields and Energy

MIT OpenCourseWare http://ocw.mit.edu Haus, Hermann A., and James R. Melcher. Electromagnetic Fields and Energy. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1989. ISBN: 9780132490207. Please use the following citation format: Haus, Hermann A., and James R. Melcher, Electromagnetic Fields and Energy. (Massachusetts Institute of Technology: MIT OpenCourseWare). http://ocw.mit.edu (accessed [Date]). License: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike. Also available from Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1989. ISBN: 9780132490207. Note: Please use the actual date you accessed this material in your citation. For more information about citing these materials or our Terms of Use, visit: http://ocw.mit.edu/terms 9 MAGNETIZATION 9.0 INTRODUCTION The sources of the magnetic fields considered in Chap. 8 were conduction currents associated with the motion of unpaired charge carriers through materials. Typically, the current was in a metal and the carriers were conduction electrons. In this chapter, we recognize that materials provide still other magnetic field sources. These account for the fields of permanent magnets and for the increase in inductance produced in a coil by insertion of a magnetizable material. Magnetization effects are due to the propensity of the atomic constituents of matter to behave as magnetic dipoles. It is natural to think of electrons circulating around a nucleus as comprising a circulating current, and hence giving rise to a magnetic moment similar to that for a current loop, as discussed in Example 8.3.2. More surprising is the magnetic dipole moment found for individual electrons. This moment, associated with the electronic property of spin, is defined as the Bohr magneton e 1 m = ± ¯h (1) e m 2 11 where e/m is the electronic chargetomass ratio, 1.76 × 10 coulomb/kg, and 2π¯h −34 2 is Planck’s constant, ¯h = 1.05 × 10 joulesec so that me has the units A − m . -

Physics and Measurements of Magnetic Materials

Physics and measurements of magnetic materials S. Sgobba CERN, Geneva, Switzerland Abstract Magnetic materials, both hard and soft, are used extensively in several components of particle accelerators. Magnetically soft iron–nickel alloys are used as shields for the vacuum chambers of accelerator injection and extraction septa; Fe-based material is widely employed for cores of accelerator and experiment magnets; soft spinel ferrites are used in collimators to damp trapped modes; innovative materials such as amorphous or nanocrystalline core materials are envisaged in transformers for high- frequency polyphase resonant convertors for application to the International Linear Collider (ILC). In the field of fusion, for induction cores of the linac of heavy-ion inertial fusion energy accelerators, based on induction accelerators requiring some 107 kg of magnetic materials, nanocrystalline materials would show the best performance in terms of core losses for magnetization rates as high as 105 T/s to 107 T/s. After a review of the magnetic properties of materials and the different types of magnetic behaviour, this paper deals with metallurgical aspects of magnetism. The influence of the metallurgy and metalworking processes of materials on their microstructure and magnetic properties is studied for different categories of soft magnetic materials relevant for accelerator technology. Their metallurgy is extensively treated. Innovative materials such as iron powder core materials, amorphous and nanocrystalline materials are also studied. A section considers the measurement, both destructive and non-destructive, of magnetic properties. Finally, a section discusses magnetic lag effects. 1 Magnetic properties of materials: types of magnetic behaviour The sense of the word ‘lodestone’ (waystone) as magnetic oxide of iron (magnetite, Fe3O4) is from 1515, while the old name ‘lodestar’ for the pole star, as the star leading the way in navigation, is from 1374. -

A Problem-Solving Approach – Chapter 5: the Magnetic Field

chapter S the magnetic field 314 The Magnetic Field The ancient Chinese knew that the iron oxide magnetite (FesO 4 ) attracted small pieces of iron. The first application of this effect was the navigation compass, which was not developed until the thirteenth century. No major advances were made again until the early nineteenth century when precise experiments discovered the properties of the magnetic field. 5-1 FORCES ON MOVING CHARGES 5-1-1 The Lorentz Force Law It was well known that magnets exert forces on each other, but in 1820 Oersted discovered that a magnet placed near a current carrying wire will align itself perpendicular to the wire. Each charge q in the wire, moving with velocity v in the magnetic field B [teslas, (kg-s 2 -A-')], felt the empirically determined Lorentz force perpendicular to both v and B f =q(vx B) (1) as illustrated in Figure 5-1. A distribution of charge feels a differential force df on each moving incremental charge element dq: df = dq(vx B) (2) V B q f q(v x B) Figure 5-1 A charge moving through a magnetic field experiences the Lorentz force perpendicular to both its motion and the magnetic field. Forces on Moving Charges 315 Moving charges over a line, surface, or volume, respectively constitute line, surface, and volume currents, as in Figure 5-2, where (2) becomes pfv x B dV= Jx B dV (J = pfv, volume current density) dS df= a-vxB dS=KXB (K = orfv, surface current density) (3) AfvxB dl =IxB dl (I=Afv, line current) B v : -- I dl =--ev di df = Idl x B (a) B dS K dS di > d1 KdSx B (b) B d V 1K----------+-. -

Measuring the Magnetization of a Permanent Magnet B

Measuring the magnetization of a permanent magnet B. Barman Department of Computer Science, Engineering and Physics, University of Michigan-Flint, Flint, Michigan 48502 A. Petrou Department of Physics, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York, Buffalo, New York 14260 (Received 1 July 2018; accepted 10 February 2019) The effect of an external magnetic field B on magnetic materials is a subject of immense importance. The simplest and oldest manifestation of such effects is the behavior of the magnetic compass. Magnetization M plays a key role in studying the response of magnetic materials to B. In this paper, an experimental technique for the determination of M of a permanent magnet will be presented. The proposed method discusses the effect of B (produced by a pair of Helmholtz coils) on a permanent magnet, suspended by two strings and allowed to oscillate under the influence of the torque that the magnetic field exerts on the magnet. The arrangement used Newton’s second law for rotational motion to measure M via graphical analysis. VC 2019 American Association of Physics Teachers. https://doi.org/10.1119/1.5092452 1,5–7 I. INTRODUCTION of the loop. The magnitude l is given by the following equation: Magnetism has been intriguing mankind for centuries now. A magnet’s ability to influence magnetic materials, l ¼ iA: (1) from a distance, mesmerized numerous inquisitive minds of the past. The magnetic compass, used across all continents, If we place this loop in a uniform magnetic field B~ at an is such a device, acting under the influence of Earth’s mag- angle h with ~l, as shown in Fig. -

Magnetostatics in Electrostatics, Electric Fields Constant in Time Are Produced by Stationary Charges

Section 5: Magnetostatics In electrostatics, electric fields constant in time are produced by stationary charges. In magnetostatics magnetic fields constant in time are produced by steady currents. Electric currents The electric current in a wire is the charge per unit time passing a given point. If charge dQ passes point P in Fig.5.1 per time dt the magnitude of the current is dQ I . (5.1) dt By definition, negative charges moving to the left count the same as positive charges moving to the right. In practice, there is a convention to assume that the electric current flows in the direction of motion of positive charges. Current is measured in coulombs-per-second, or amperes (A): 1A=1C/s. A line charge traveling down a wire at speed v (Fig. 5.1) constitutes a current Iv . (5.2) This is because a segment of length vt, carrying charge vt, passes point P in a time interval t. Fig. 5.1 Line current We note that current is actually a vector. A neutral wire, of course, contains as many stationary positive charges as mobile negative ones. The former do not contribute to the current. When charge flows over a surface, we describe it by the surface current density, K, defined as follows: Consider a “ribbon” of infinitesimal width dl , running parallel to the flow (Fig. 5.2). If the current in this ribbon is dI, the surface current density is dI K . (5.3) dl In words, K is the current per unit width-perpendicular-to-flow. In particular, if the mobile surface charge density is and its velocity is v, then Kv .