Introductory Physics Laboratory, Faculty of Physics and Geosciences, University of Leipzig

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basic Magnetic Measurement Methods

Basic magnetic measurement methods Magnetic measurements in nanoelectronics 1. Vibrating sample magnetometry and related methods 2. Magnetooptical methods 3. Other methods Introduction Magnetization is a quantity of interest in many measurements involving spintronic materials ● Biot-Savart law (1820) (Jean-Baptiste Biot (1774-1862), Félix Savart (1791-1841)) Magnetic field (the proper name is magnetic flux density [1]*) of a current carrying piece of conductor is given by: μ 0 I dl̂ ×⃗r − − ⃗ 7 1 - vacuum permeability d B= μ 0=4 π10 Hm 4 π ∣⃗r∣3 ● The unit of the magnetic flux density, Tesla (1 T=1 Wb/m2), as a derive unit of Si must be based on some measurement (force, magnetic resonance) *the alternative name is magnetic induction Introduction Magnetization is a quantity of interest in many measurements involving spintronic materials ● Biot-Savart law (1820) (Jean-Baptiste Biot (1774-1862), Félix Savart (1791-1841)) Magnetic field (the proper name is magnetic flux density [1]*) of a current carrying piece of conductor is given by: μ 0 I dl̂ ×⃗r − − ⃗ 7 1 - vacuum permeability d B= μ 0=4 π10 Hm 4 π ∣⃗r∣3 ● The Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (German national metrology institute) maintains a unit Tesla in form of coils with coil constant k (ratio of the magnetic flux density to the coil current) determined based on NMR measurements graphics from: http://www.ptb.de/cms/fileadmin/internet/fachabteilungen/abteilung_2/2.5_halbleiterphysik_und_magnetismus/2.51/realization.pdf *the alternative name is magnetic induction Introduction It -

Electrostatics Vs Magnetostatics Electrostatics Magnetostatics

Electrostatics vs Magnetostatics Electrostatics Magnetostatics Stationary charges ⇒ Constant Electric Field Steady currents ⇒ Constant Magnetic Field Coulomb’s Law Biot-Savart’s Law 1 ̂ ̂ 4 4 (Inverse Square Law) (Inverse Square Law) Electric field is the negative gradient of the Magnetic field is the curl of magnetic vector electric scalar potential. potential. 1 ′ ′ ′ ′ 4 |′| 4 |′| Electric Scalar Potential Magnetic Vector Potential Three Poisson’s equations for solving Poisson’s equation for solving electric scalar magnetic vector potential potential. Discrete 2 Physical Dipole ′′′ Continuous Magnetic Dipole Moment Electric Dipole Moment 1 1 1 3 ∙̂̂ 3 ∙̂̂ 4 4 Electric field cause by an electric dipole Magnetic field cause by a magnetic dipole Torque on an electric dipole Torque on a magnetic dipole ∙ ∙ Electric force on an electric dipole Magnetic force on a magnetic dipole ∙ ∙ Electric Potential Energy Magnetic Potential Energy of an electric dipole of a magnetic dipole Electric Dipole Moment per unit volume Magnetic Dipole Moment per unit volume (Polarisation) (Magnetisation) ∙ Volume Bound Charge Density Volume Bound Current Density ∙ Surface Bound Charge Density Surface Bound Current Density Volume Charge Density Volume Current Density Net , Free , Bound Net , Free , Bound Volume Charge Volume Current Net , Free , Bound Net ,Free , Bound 1 = Electric field = Magnetic field = Electric Displacement = Auxiliary -

Module 3 : MAGNETIC FIELD Lecture 20 : Magnetism in Matter

Module 3 : MAGNETIC FIELD Lecture 20 : Magnetism in Matter Objectives In this lecture you will learn the following Study magnetic properties of matter. Express Ampere's law in the presence of magnetic matter. Define magnetization and H-vector. Understand displacement current. Assemble all the Maxwell's equations together. Study properties and propagation of electromagnetic waves in vacuum. Magnetism in Matter In our discussion on electrostatics, we have seen that in the presence of an electric field, a dielectric gets polarized, leading to bound charges. The polarization vector is, in general, in the direction of the applied electric field. A similar phenomenon occurs when a material medium is subjected to an external magnetic field. However, unlike the behaviour of dielectrics in electric field, different types of material behave in different ways when an external magnetic field is applied. We have seen that the source of magnetic field is electric current. The circulating electrons in an atom, being tiny current loops, constitute a magnetic dipole with a magnetic moment whose direction depends on the direction in which the electron is moving. An atom as a whole, may or may not have a net magnetic moment depending on the way the moments due to different elecronic orbits add up. (The situation gets further complicated because of electron spin, which is a purely quantum concept, that provides an intrinsic magnetic moment to an electron.) In the absence of a magnetic field, the atomic moments in a material are randomly oriented and consequently the net magnetic moment of the material is zero. However, in the presence of a magnetic field, the substance may acquire a net magnetic moment either in the direction of the applied field or in a direction opposite to it. -

Magnetism in Transition Metal Complexes

Magnetism for Chemists I. Introduction to Magnetism II. Survey of Magnetic Behavior III. Van Vleck’s Equation III. Applications A. Complexed ions and SOC B. Inter-Atomic Magnetic “Exchange” Interactions © 2012, K.S. Suslick Magnetism Intro 1. Magnetic properties depend on # of unpaired e- and how they interact with one another. 2. Magnetic susceptibility measures ease of alignment of electron spins in an external magnetic field . 3. Magnetic response of e- to an external magnetic field ~ 1000 times that of even the most magnetic nuclei. 4. Best definition of a magnet: a solid in which more electrons point in one direction than in any other direction © 2012, K.S. Suslick 1 Uses of Magnetic Susceptibility 1. Determine # of unpaired e- 2. Magnitude of Spin-Orbit Coupling. 3. Thermal populations of low lying excited states (e.g., spin-crossover complexes). 4. Intra- and Inter- Molecular magnetic exchange interactions. © 2012, K.S. Suslick Response to a Magnetic Field • For a given Hexternal, the magnetic field in the material is B B = Magnetic Induction (tesla) inside the material current I • Magnetic susceptibility, (dimensionless) B > 0 measures the vacuum = 0 material response < 0 relative to a vacuum. H © 2012, K.S. Suslick 2 Magnetic field definitions B – magnetic induction Two quantities H – magnetic intensity describing a magnetic field (Système Internationale, SI) In vacuum: B = µ0H -7 -2 µ0 = 4π · 10 N A - the permeability of free space (the permeability constant) B = H (cgs: centimeter, gram, second) © 2012, K.S. Suslick Magnetism: Definitions The magnetic field inside a substance differs from the free- space value of the applied field: → → → H = H0 + ∆H inside sample applied field shielding/deshielding due to induced internal field Usually, this equation is rewritten as (physicists use B for H): → → → B = H0 + 4 π M magnetic induction magnetization (mag. -

Magnetic Hysteresis

Magnetic hysteresis Magnetic hysteresis* 1.General properties of magnetic hysteresis 2.Rate-dependent hysteresis 3.Preisach model *this is virtually the same lecture as the one I had in 2012 at IFM PAN/Poznań; there are only small changes/corrections Urbaniak Urbaniak J. Alloys Compd. 454, 57 (2008) M[a.u.] -2 -1 M(H) hysteresesof thin filmsM(H) 0 1 2 Co(0.6 Co(0.6 nm)/Au(1.9 nm)] [Ni Ni 80 -0.5 80 Fe Fe 20 20 (2 nm)/Au(1.9(2 nm)/ (38 nm) (38 Magnetic materials nanoelectronics... in materials Magnetic H[kA/m] 0.0 10 0.5 J. Magn. Magn. Mater. Mater. Magn. J. Magn. 190 , 187 (1998) 187 , Ni 80 Fe 20 (4nm)/Mn 83 Ir 17 (15nm)/Co 70 Fe 30 (3 nm)/Al(1.4nm)+Ox/Ni Ni 83 Fe 17 80 (2 nm)/Cu(2 nm) Fe 20 (4 nm)/Ta(3 nm) nm)/Ta(3 (4 Phys. Stat. Sol. (a) 199, 284 (2003) Phys. Stat. Sol. (a) 186, 423 (2001) M(H) hysteresis ●A hysteresis loop can be expressed in terms of B(H) or M(H) curves. ●In soft magnetic materials (small Hs) both descriptions differ negligibly [1]. ●In hard magnetic materials both descriptions differ significantly leading to two possible definitions of coercive field (and coercivity- see lecture 2). ●M(H) curve better reflects the intrinsic properties of magnetic materials. B, M Hc2 H Hc1 Urbaniak Magnetic materials in nanoelectronics... M(H) hysteresis – vector picture Because field H and magnetization M are vector quantities the full description of hysteresis should include information about the magnetization component perpendicular to the applied field – it gives more information than the scalar measurement. -

Ferroelectric Hysteresis Measurement & Analysis

NPL Report CMMT(A) 152 Ferroelectric Hysteresis Measurement & Analysis M. Stewart & M. G. Cain National Physical Laboratory D. A. Hall University of Manchester May 1999 Ferroelectric Hysteresis Measurement & Analysis M. Stewart & M. G. Cain Centre for Materials Measurement and Technology National Physical Laboratory Teddington, Middlesex, TW11 0LW, UK. D. A. Hall Manchester Materials Science Centre University of Manchester and UMIST Manchester, M1 7HS, UK. Summary It has become increasingly important to characterise the performance of piezoelectric materials under conditions relevant to their application. Piezoelectric materials are being operated at ever increasing stresses, either for high power acoustic generation or high load/stress actuation, for example. Thus, measurements of properties such as, permittivity (capacitance), dielectric loss, and piezoelectric displacement at high driving voltages are required, which can be used either in device design or materials processing to enable the production of an enhanced, more competitive product. Techniques used to measure these properties have been developed during the DTI funded CAM7 programme and this report aims to enable a user to set up one of these facilities, namely a polarisation hysteresis loop measurement system. The report describes the technique, some example hardware implementations, and the software algorithms used to perform the measurements. A version of the software is included which, although does not allow control of experimental equipment, does include all the analysis features and will allow analysis of data captured independently. ã Crown copyright 1999 Reproduced by permission of the Controller of HMSO ISSN 1368-6550 May 1999 National Physical Laboratory Teddington, Middlesex, United Kingdom, TW11 0LW Extracts from this report may be reproduced provided the source is acknowledged. -

EM4: Magnetic Hysteresis – Lab Manual – (Version 1.001A)

CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY GOTEBORÄ G UNIVERSITY EM4: Magnetic Hysteresis { Lab manual { (version 1.001a) Students: ........................................... & ........................................... Date: .... / .... / .... Laboration passed: ........................ Supervisor: ........................................... Date: .... / .... / .... Raluca Morjan Sergey Prasalovich April 7, 2003 Magnetic Hysteresis 1 Aims: In this laboratory session you will learn about the basic principles of mag- netic hysteresis; learn about the properties of ferromagnetic materials and determine their dissipation energy of remagnetization. Questions: (Please answer on the following questions before coming to the laboratory) 1) What classes of magnetic materials do you know? 2) What is a `magnetic domain'? 3) What is a `magnetic permeability' and `relative permeability'? 4) What is a `hysteresis loop' and how it can be recorded? (How you can measure a magnetization and magnetic ¯eld indirectly?) 5) What is a `saturation point' and `magnetization curve' for a hysteresis loop? 6) How one can demagnetize a ferromagnet? 7) What is the energy dissipation in one full hysteresis loop and how it can be calculated from an experiment? Equipment list: 1 Sensor-CASSY 1 U-core with yoke 2 Coils (N = 500 turnes, L = 2,2 mH) 1 Clamping device 1 Function generator S12 2 12 V DC power supplies 1 STE resistor 1, 2W 1 Socket board section 1 Connecting lead, 50 cm 7 Connecting leads, 100 cm 1 PC with Windows 98 and CASSY Lab software Magnetic Hysteresis 2 Introduction In general, term \hysteresis" (comes from Greek \hyst¶erÄesis", - lag, delay) means that value describing some physical process is ambiguously dependent on an external parameter and antecedent history of that value must be taken into account. The term was added to the vocabulary of physical science by J. -

Magnetic Materials: Hysteresis

Magnetic Materials: Hysteresis Ferromagnetic and ferrimagnetic materials have non-linear initial magnetisation curves (i.e. the dotted lines in figure 7), as the changing magnetisation with applied field is due to a change in the magnetic domain structure. These materials also show hysteresis and the magnetisation does not return to zero after the application of a magnetic field. Figure 7 shows a typical hysteresis loop; the two loops represent the same data, however, the blue loop is the polarisation (J = µoM = B-µoH) and the red loop is the induction, both plotted against the applied field. Figure 7: A typical hysteresis loop for a ferro- or ferri- magnetic material. Illustrated in the first quadrant of the loop is the initial magnetisation curve (dotted line), which shows the increase in polarisation (and induction) on the application of a field to an unmagnetised sample. In the first quadrant the polarisation and applied field are both positive, i.e. they are in the same direction. The polarisation increases initially by the growth of favourably oriented domains, which will be magnetised in the easy direction of the crystal. When the polarisation can increase no further by the growth of domains, the direction of magnetisation of the domains then rotates away from the easy axis to align with the field. When all of the domains have fully aligned with the applied field saturation is reached and the polarisation can increase no further. If the field is removed the polarisation returns along the solid red line to the y-axis (i.e. H=0), and the domains will return to their easy direction of magnetisation, resulting in a decrease in polarisation. -

Hysteresis in Muscle

International Journal of Bifurcation and Chaos Accepted for publication on 19th October 2016 HYSTERESIS IN MUSCLE Jorgelina Ramos School of Healthcare Science, Manchester Metropolitan University, Chester St., Manchester M1 5GD, United Kingdom, [email protected] Stephen Lynch School of Computing, Mathematics and Digital Technology, Manchester Metropolitan University, Chester St., Manchester M1 5GD, United Kingdom, [email protected] David Jones School of Healthcare Science, Manchester Metropolitan University, Chester St., Manchester M1 5GD, United Kingdom, [email protected] Hans Degens School of Healthcare Science, Manchester Metropolitan University, Chester St., Manchester M1 5GD, United Kingdom, and Lithuanian Sports University, Kaunas, Lithuania. [email protected] This paper presents examples of hysteresis from a broad range of scientific disciplines and demon- strates a variety of forms including clockwise, counterclockwise, butterfly, pinched and kiss-and- go, respectively. These examples include mechanical systems made up of springs and dampers which have been the main components of muscle models for nearly one hundred years. For the first time, as far as the authors are aware, hysteresis is demonstrated in single fibre muscle when subjected to both lengthening and shortening periodic contractions. The hysteresis observed in the experiments is of two forms. Without any relaxation at the end of lengthening or short- ening, the hysteresis loop is a convex clockwise loop, whereas a concave clockwise hysteresis loop (labeled as kiss-and-go) is formed when the muscle is relaxed at the end of lengthening and shortening. This paper also presents a mathematical model which reproduces the hysteresis curves in the same form as the experimental data. -

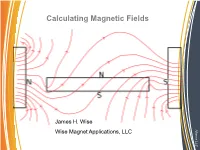

Calculating Magnetic Fields, Please Call

Calculating Magnetic Fields James H. Wise Alliance LLC Alliance Wise Magnet Applications, LLC Magnetic Fields: What and Where? Magnetic fields: Sources: • Appear around electric currents • Surround magnetic materials Properties: • They have a direction • They possess magnitude • They are vector fields Alliance LLC Alliance Reference for Definition Field descriptions and behavior See Chapters 1, 2 and 3 of “The Feynman Lectures in Physics”, Vol.II by Feynman, Leighton and Sands, Addison Wesley,1964, ISBN 0 -201-2117-X-P . Chapter 1 is my favorite starting point for thinking about fields. The next slide is derived from that. Alliance LLC Alliance Examples of Fields Fields: • When a quantity varies with location in space, (x,y,z,t), it is said to be a field. • Temperature around a heat source forms a field. • As the temperature is only a single quantity associated with it is said to be a scalar field • Heat flow has a direction and thus 3 quantities that change with (x,y,z) and perhaps a time dependence • Because it has 3 spatial components obeying the rules of vectors, it is said to be a vector field. Alliance LLC Alliance Magnetic Fields of Permanent Magnets • The magnetic field was originally treated as originating from charges. • Pole strength was interpreted as the amount of magnetic charge on the surface of a magnet If the charge distribution was known, the force outside the magnet could be computed correctly • The charge model does not give the correct results for fields inside magnets. • The pole model is useful for gaining an intuitive view for qualitative results. -

Electromagnetism 3. Magnetization (Lectures 7–9)

Electromagnetism Handout 3: 3. Magnetization (Lectures 7{9): Here is the proof of a useful vector identity. First recall Stokes' theorem which states that Z I r × A · dS = A · dl: (1) Let us suppose that A takes the form A(r) = f(r)c where c 6= c(r) is a constant vector. Hence we have r × A = fr × c − c × rf = −c × rf (2) since r × c = 0 (because c is a constant vector, its derivative vanishes). Stokes' theorem then gives us I I Z Z A · dl = c · f dl = − c × rf · dS = −c · rf × dS; (3) but this is true for any c and so I Z f dl = − rf × dS: (4) Now let us choose f = r^ · r0 and take the gradient and integral around a closed loop in the primed coordinates: I Z Z (r^ · r0) dl0 = − r0(r^ · r0) × dS0 = −r^ × dS0 (5) which works because r0(r^ · r0) = r^. In summary: I Z r^ · r0 dl0 = dS0 × r^: (6) We will use this to show that the magnetic vector potential from a magnetic dipole is given by µ A = 0 m × r^; (7) 4πr2 where m is the magnetic dipole moment. For example, if we put m parallel to z and use spherical polars, we have that µ A = 0 m sin θ φ^; (8) 4πr2 and so 1 @ 1 @ B = r × A(r) = (r sin θ A )r^ − (r sin θ A )θ^; (9) r2 sin θ @θ φ r sin θ @r φ because Ar = Aθ = 0 and hence µ m 2 cos θ sin θ B = 0 r^ + θ^ ; (10) 4π r3 r3 which is the same form as an electric dipole. -

Passive Magnetic Attitude Control for Cubesat Spacecraft

SSC10-XXXX-X Passive Magnetic Attitude Control for CubeSat Spacecraft David T. Gerhardt University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309 Scott E. Palo Advisor, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309 CubeSats are a growing and increasingly valuable asset specifically to the space sciences community. However, due to their small size CubeSats provide limited mass (< 4 kg) and power (typically < 6W insolated) which must be judiciously allocated between bus and instrumentation. There are a class of science missions that have pointing requirements of 10-20 degrees. Passive Magnetic Attitude Control (PMAC) is a wise choice for such a mission class, as it can be used to align a CubeSat within ±10◦ of the earth's magnetic field at a cost of zero power and < 50g mass. One example is the Colorado Student Space Weather Experiment (CSSWE), a 3U CubeSat for space weather investigation. The design of a PMAC system is presented for a general 3U CubeSat with CSSWE as an example. Design aspects considered include: external torques acting on the craft, magnetic parametric resonance for polar orbits, and the effect of hysteresis rod dimensions on dampening supplied by the rod. Next, the development of a PMAC simulation is discussed, including the equations of motion, a model of the earth's magnetic field, and hysteresis rod response. Key steps of the simulation are outlined in sufficient detail to recreate the simulation. Finally, the simulation is used to verify the PMAC system design, finding that CSSWE settles to within 10◦ of magnetic field lines after 6.5 days. Introduction OLUTIONS for satellite attitude control must Sbe weighed by trading system resource allocation against performance.